Al-Harith ibn Jabalah

| Al-Harith V ibn Jabalah | |

|---|---|

| King of the Ghassanids, Roman Patrician and Phylarch of the Saracens | |

| Reign | c. 529 – 569 |

| Predecessor | Jabalah IV |

| Successor | Al-Mundhir III |

| Died | 569 |

| Father | Jabalah IV |

Al-Ḥārith ibn Jabalah (Arabic: الحارث بن جبلة; [Flavios] Arethas ([Φλάβιος] Ἀρέθας) in Greek sources[1] and Khālid ibn Jabalah (خالد بن جبلة) in later Islamic sources),[2][3] was a king of the Ghassanids, a pre-Islamic Arab people who lived on the eastern frontier of the Byzantine Empire. The fifth Ghassanid ruler of that name, he reigned from c. 528 to 569 and played a major role in the wars with Persia and the affairs of the Monophysite Syriac Church. For his services to Byzantium, he was made a patricius and a gloriosissimus.[4]

Biography

Early life

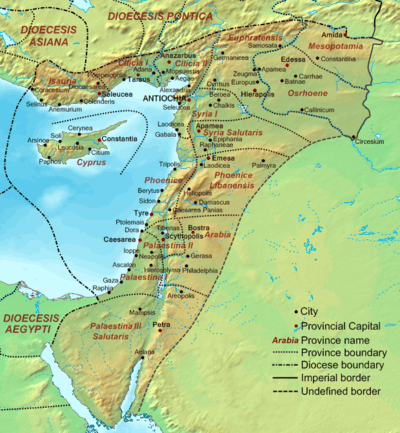

Harith was the son of Jabalah (Gabalas in Greek sources) and brother of Abu Karib (Abocharabus), phylarch of Palaestina Tertia.[5] He became ruler of the Ghassanids and phylarch of Arabia Petraea and Palaestina Secunda probably in 528, following the death of his father in the Battle of Thannuris. Soon after (c. 529) he was raised by the Byzantine emperor Justinian I (r. 527–565), in the words of the historian Procopius, "to the dignity of king", becoming the overall commander of all the Empire's Arab allies (foederati) in the East with the title of patrikios (πατρίκιος καὶ φύλαρχος τῶν Σαρακηνῶν, "patrician and phylarch of the Saracens"). His actual area of control, however, may initially have been limited to the northeastern part of Byzantium's Arab frontier.[4][6][7][8] At the time, the Byzantines and their Arab allies were engaged in a war against the Sassanid Persians and their Arab clients, the Lakhmids, and Justinian's move was designed to create a counterpart to the powerful Lakhmid ruler, Mundhir, who controlled the Arab tribes allied to the Persians.[7][9]

Military career

In this capacity, Harith fought on behalf of the Byzantines in all their numerous wars against Persia.[4] Already in 528 he was one of the commanders sent in a punitive expedition against Mundhir.[11][12] In 529, he helped suppress the wide-scale Samaritan revolt, capturing 20,000 boys and girls whom he sold as slaves. It was perhaps Harith's successful participation in this conflict that led Justinian to promote him to supreme phylarch.[13] It is possible that he took part with his men in the Byzantine victory at Daras in 530, although no source explicitly mentions him.[14] In 531, he led a 5,000-strong Arab contingent in the Battle of Callinicum. Procopius, a source hostile to the Ghassanid ruler, states that the Arabs, stationed on the Byzantine right, betrayed the Byzantines and fled, costing them the battle. John Malalas, however, whose record is generally more reliable, reports that while some Arabs indeed fled, Harith stood firm.[12][15] The charge of treason levelled by Procopius against Harith seems to be further undermined by the fact that, unlike Belisarius, he was retained in command and was active in operations around Martyropolis later in the year.[16]

In 537/538 or 539, he clashed with Mundhir of the Lakhmids over grazing rights on the lands south of Palmyra, near the old Strata Diocletiana.[12][17] According to later accounts by Tabari, the Ghassanid ruler invaded Mundhir's territory and carried off rich booty. The Persian ruler, Khosrau I (r. 531–579), used this dispute as a pretext for restarting hostilities with the Byzantines, and renewed war broke out in 540.[3] In the campaign of 541, Harith and his men, accompanied by 1200 Byzantines under generals John the Glutton and Trajan, were sent by Belisarius into a raid into Assyria. The expedition was successful, penetrated far into enemy territory and gathered much plunder. At some point, however, the Byzantine contingent was sent back, and subsequently Harith failed to either meet up with or inform Belisarius of his whereabouts. According to Procopius's account, this, in addition to the outbreak of a disease among the army, forced Belisarius to withdraw. Procopius further alleges that this was done deliberately so that the Arabs would not have to share their plunder. In his Secret History, however, Procopius gives a different account of Belisarius's inaction, completely unrelated to the Ghassanid ruler.[12][18] In c. 544/545, Harith was involved in armed conflict with another Arab phylarch, al-Aswad, known in Greek as Asouades.[19]

From c. 546 on, while the two great empires were at peace in Mesopotamia after the truce of 545, the conflict between their Arab allies continued. In a sudden raid, Mundhir captured one of Harith's sons and had him sacrificed. Soon after, however, the Lakhmids suffered a heavy defeat in a pitched battle between the two Arab armies.[20] The conflict continued, with Mundhir staging repeated raids into Syria. In one of these raids, in June 554, Harith met him in the decisive battle of Yawm Halima (the "Day of Halima"), celebrated in pre-Islamic Arab poetry, near Chalcis, at which the Lakhmids were defeated. Mundhir fell in the field, but Harith also lost his eldest son Jabalah.[21]

In November 563, Harith visited Emperor Justinian in Constantinople, to discuss his succession and the raids against his domains by the Lakhmid ruler 'Amr, who was eventually bought off by Justinian.[22][23] He certainly left a vivid impression in the imperial capital, not least by his physical presence: John of Ephesus records that years later, the Emperor Justin II (r. 565–578), who had descended into madness, was frightened and went to hide himself when he was told "Arethas is coming for you".[24]

Death

When al-Harith died in 569 during a supposed earthquake,[25] he was succeeded by his son al-Mundhir (Alamoundaros in Byzantine sources). Taking advantage of this, the new Lakhmid ruler Qabus launched an attack, but was decisively defeated.[22][26]

Religious policies

In contrast to his Byzantine overlords, Harith was a staunch Monophysite and rejected the Council of Chalcedon. Throughout his rule, al-Harith supported the anti-Chalcedonian tendencies in the region of Syria, presiding over church councils and engaging in theology, contributing actively to the Monophysite church's revival during the 6th century.[4][27] Thus in 542, following two decades of persecutions which had decapitated the Monophysite leadership, he appealed for the appointment of new Monophysite bishops in Syria to the Empress Theodora, whose own Monophysite leanings were well-known. Theodora then appointed Jacob Baradaeus and Theodore as bishops. Jacob in particular would prove a very capable leader, converting pagans and greatly expanding and strengthening the organization of the Monophysite church.[4][22][28]

References

Citations

- ↑ Shahîd 1995, pp. 260, 294–297.

- ↑ Shahîd 1995, pp. 216–217.

- 1 2 Greatrex & Lieu 2002, pp. 102–103.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kazhdan 1991, p. 163.

- ↑ Martindale, Jones & Morris 1992, p. 111; Shahîd 1995, p. 69.

- ↑ Martindale, Jones & Morris 1992, pp. 111–112.

- 1 2 Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 88.

- ↑ Shahîd 1995, pp. 84–85, 95–109.

- ↑ Shahîd 1995, p. 63.

- ↑ Shahîd 1995, p. 357.

- ↑ Shahîd 1995, pp. 70–75.

- 1 2 3 4 Martindale, Jones & Morris 1992, p. 112.

- ↑ Shahîd 1995, pp. 82–89.

- ↑ Shahîd 1995, pp. 132–133.

- ↑ Greatrex & Lieu 2002, pp. 92–93; Shahîd 1995, pp. 133–142.

- ↑ Shahîd 1995, p. 142.

- ↑ Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 102; Shahîd 1995, pp. 209–210.

- ↑ Greatrex & Lieu 2002, pp. 108–109; Shahîd 1995, pp. 220–223, 226–230.

- ↑ Martindale, Jones & Morris 1992, pp. 112, 137.

- ↑ Martindale, Jones & Morris 1992, pp. 112–113; Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 123; Shahîd 1995, pp. 237–239.

- ↑ Martindale, Jones & Morris 1992, pp. 111, 113; Greatrex & Lieu 2002, pp. 129–130.

- 1 2 3 Martindale, Jones & Morris 1992, p. 113.

- ↑ Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 135; Shahîd 1995, pp. 282–288.

- ↑ Shahîd 1995, p. 288.

- ↑ Shahîd 1995, p. 337.

- ↑ Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 136.

- ↑ Shahîd 1995, pp. 225–226.

- ↑ Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 112.

Sources

- Greatrex, Geoffrey; Lieu, Samuel N. C. (2002). The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars (Part II, 363–630 AD). London, United Kingdom: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-14687-9.

- Kazhdan, Alexander Petrovich, ed. (1991). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. New York, New York and Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6.

- Martindale, John Robert; Jones, Arnold Hugh Martin; Morris, J., eds. (1992). The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, Volume III: A.D. 527–641. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20160-5.

- Shahîd, Irfan (1995). Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, Volume 1. Washington, District of Columbia: Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 978-0-88402-214-5.