Airy beam

An Airy beam is a non-diffracting waveform which gives the appearance of curving as it travels.

Physical description

A cross section of an ideal Airy beam would reveal an area of principal intensity, with a series of adjacent, less luminous areas trailing off to infinity. In reality, the beam is truncated so as to have a finite composition.

As the beam propagates, it does not diffract, i.e., does not spread out. The Airy beam also has the characteristic of freely accelerating. As it propagates, it bends so as to form a parabolic arc.

History

The term "Airy beam" derives from the Airy integral, developed in the 1830s by Sir George Biddell Airy to explain optical caustics such as those appearing in a rainbow.[1]

The Airy waveform was first theorized in 1979 by M. V. Berry and Nándor L. Balázs. They demonstrated a nonspreading Airy wave packet solution to the Schrödinger equation.[2]

In 2007 researchers from the University of Central Florida were able to create and observe an Airy beam for the first time in both one- and two-dimensional configurations. The members of the team were Georgios Siviloglou, John Broky, Aristide Dogariu, and Demetrios Christodoulides.[3]

In one-dimension, the Airy beam is the only exactly shape-preserving accelerating solution to the free-particle Schrödinger equation (or 2D paraxial wave equation). However, in two dimensions (or 3D paraxial systems), two separable solutions are possible: two-dimensional Airy beams and accelerating parabolic beams.[4] Furthermore, it has been shown [5] that any function on the real line can be mapped to an accelerating beam with a different transverse shape.

Since 2009 accelerating "Airy like" beams have been observed in non-linear systems[6][7][8][9] and have been demonstrated for even for other types of equations such as Helmholtz equation, Maxwell's equations.[10][11] Acceleration can also take place along a radial instead of a cartesian coordinate, which is the case of circular-Airy abruptly autofocusing waves [12] and their extension to arbitrary (nonparabolic) caustics.[13] Acceleration is possible even for non-homogeneous periodic systems.[14][15] With careful engineering of the input waveform, light can be made to accelerate along arbitrary trajectories in media that possess discrete [16] or continuous [17] periodicity.

Mathematical description

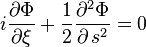

The potential free Schrödinger equation:

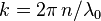

Has the following Airy accelerating solution:[18]

where

-

is the Airy function.

is the Airy function. -

is the electric field envelope

is the electric field envelope -

represents a dimensionless traverse coordinate

represents a dimensionless traverse coordinate -

is an arbitrary traverse scale

is an arbitrary traverse scale -

is a normalized propagation distance

is a normalized propagation distance -

-

this solution is non-diffracting in parabolic accelerating frame. Actually one can perform a coordinate transformation and get an Airy equation. In the new coordinates the equation solved by the Airy function.

Experimental observation

Georgios Sivilioglou, et al. successfully fabricated an Airy beam in 2007. A beam with a Gaussian distribution was modulated by a spatial light modulator to have an Airy distribution. The result was recorded by a CCD camera.[3][1]

Applications

Researchers at the University of St. Andrews have used Airy beams to manipulate small particles, moving them along curves and around corners. This may find use in fields such as microfluidic engineering and cell biology.[19] They have further utilised Airy beams to make a large field of view (FOV) while maintaining high axial contrast in light sheet microscope.[20] The accelerating and diffraction-free features of the Airy wavepacket have also been utilized by researchers at the University of Crete to produce two-dimensional, circular-Airy waves, termed abruptly-autofocusing beams.[12] These beams tend to focus in an abrupt fashion shortly before a target while maintaining a constant and low intensity profile along the propagated path and can be useful in laser microfabrication [21] or medical laser treatments.

See also

Notes and references

- 1 2 "Scientists make first observation of Airy optical beams"

- ↑ M. V. Berry and Nándor L. Balázs, Nonspreading wave packets. American Journal of Physics 47(3), 1979, pp. 264-267.

- 1 2 G. A. Siviloglou, J. Broky, A. Dogariu, and D. N. Christodoulides, Observation of Accelerating Airy Beams Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 213901 (2007).

- ↑ M.A. Bandres, "Accelerating parabolic beams," Opt. Lett. 33, 1678-1680 (2008).

- ↑ M. A. Bandres, "Accelerating beams," Opt. Lett. 34, 3791-3793 (2009).

- ↑ Parravicini, Jacopo; Minzioni, Paolo; Degiorgio, Vittorio; DelRe, Eugenio (15 December 2009). "Observation of nonlinear Airy-like beam evolution in lithium niobate". Optics Letters 34 (24). Bibcode:2009OptL...34.3908P. doi:10.1364/OL.34.003908.

- ↑ Kaminer, Ido; Segev, Mordechai; Christodoulides, Demetrios N. (30 April 2011). "Self-Accelerating Self-Trapped Optical Beams" (PDF). Physical Review Letters 106 (21). Bibcode:2011PhRvL.106u3903K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.213903.

- ↑ Kaminer, Ido; Nemirovsky, Jonathan; Segev, Mordechai (1 August 2012). "Self-accelerating self-trapped nonlinear beams of Maxwell's equations" (PDF). Optics Express 20 (17): 18827. Bibcode:2012OExpr..2018827K. doi:10.1364/OE.20.018827.

- ↑ Bekenstein, Rivka; Segev, Mordechai (7 November 2011). "Self-accelerating optical beams in highly nonlocal nonlinear media" (PDF). Optics Express 19 (24): 23706. Bibcode:2011OExpr..1923706B. doi:10.1364/OE.19.023706.

- ↑ Kaminer, Ido; Bekenstein, Rivka and Nemirovsky, Jonathan; Segev, Mordechai (2012). "Nondiffracting accelerating wave packets of Maxwell’s equations" (PDF). Physical Review Letters 108 (16): 163901. arXiv:1201.0300. Bibcode:2012PhRvL.108p3901K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.163901.

- ↑ Courvoisier, F.; Mathis, A.; Froehly, L.; Giust, R.; Furfaro, L.; Lacourt, P. A.; Jacquot, M.; Dudley, J. M. (15 May 2012). "Sending femtosecond pulses in circles: highly nonparaxial accelerating beams". Optics Letters 37 (10): 1736. arXiv:1202.3318. Bibcode:2012OptL...37.1736C. doi:10.1364/OL.37.001736.

- 1 2 Efremidis, Nikolaos; Christodoulides, Demetrios (2010). "Abruptly autofocusing waves". Optics Letters 35 (23): 4045. Bibcode:2010OptL...35.4045E. doi:10.1364/OL.35.004045.

- ↑ Chremmos, Ioannis; Efremidis, Nikolaos; Christodoulides, Demetrios (2011). "Pre-engineered abruptly autofocusing beams". Optics Letters 36 (10). Bibcode:2011OptL...36.1890C. doi:10.1364/OL.36.001890.

- ↑ El-Ganainy, Ramy; Makris, Konstantinos G.; Miri, Mohammad Ali; Christodoulides, Demetrios N.; Chen, Zhigang (31 July 2011). "Discrete beam acceleration in uniform waveguide arrays". Physical Review A 84 (2). Bibcode:2011PhRvA..84b3842E. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.84.023842.

- ↑ Kaminer, Ido; Nemirovsky, Jonathan; Makris, Konstantinos G.; Segev, Mordechai (3 April 2013). "Self-accelerating beams in photonic crystals" (PDF). Optics Express 21 (7): 8886. Bibcode:2013OExpr..21.8886K. doi:10.1364/OE.21.008886.

- ↑ Efremidis, Nikolaos; Chremmos, Ioannis (2012). "Caustic design in periodic lattices". Optics Letters 37 (7): 1277. Bibcode:2012OptL...37.1277E. doi:10.1364/OL.37.001277.

- ↑ Chremmos, Ioannis; Efremidis, Nikolaos (2012). "Band-specific phase engineering for curving and focusing light in waveguide arrays". Physical Review A 85 (063830). Bibcode:2012PhRvA..85f3830C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.85.063830.

- ↑ "Observation of Accelerating Airy Beams"

- ↑ "Light throws a curve ball"

- ↑ "Imaging turns a corner"

- ↑ Papazoglou, Dimitrios; Efremidis, Nikolaos; Christodoulides, Demetrios; Tzortzakis, Stelios (2011). "Observation of abruptly autofocusing waves". Optics Letters 36 (10). Bibcode:2011OptL...36.1842P. doi:10.1364/OL.36.001842.