Agawam, Massachusetts

| Agawam, Massachusetts | ||

|---|---|---|

| City | ||

|

Capt. Charles Leonard's house | ||

| ||

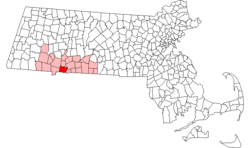

Location in Hampden County in Massachusetts | ||

Agawam, Massachusetts Location in the United States | ||

| Coordinates: 42°04′10″N 72°36′55″W / 42.06944°N 72.61528°WCoordinates: 42°04′10″N 72°36′55″W / 42.06944°N 72.61528°W | ||

| Country |

| |

| State |

| |

| County | Hampden | |

| Settled | 1636 | |

| Incorporated | 1855 | |

| Government | ||

| • Type | Mayor-council city | |

| • Mayor | Richard Cohen (D)[1][2] | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 62.8 km2 (24.2 sq mi) | |

| • Land | 60.2 km2 (23.2 sq mi) | |

| • Water | 2.6 km2 (1.0 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 27 m (90 ft) | |

| Population (2010) | ||

| • Total | 28,438 | |

| • Density | 452.8/km2 (1,175.1/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | Eastern (UTC-5) | |

| • Summer (DST) | Eastern (UTC-4) | |

| ZIP code | 01001 | |

| Area code(s) | 413 | |

| FIPS code | 25-00840 | |

| GNIS feature ID | 0608970 | |

| Website | www.agawam.ma.us | |

Agawam is a city[3] in Hampden County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 28,438 at the 2010 census. Agawam sits on the western side of the Connecticut River, directly across from Springfield, Massachusetts. It is considered part of the Springfield Metropolitan Statistical Area, which is contiguous with the Knowledge Corridor area, the 2nd largest metropolitan area in New England. Agawam contains a subsection, Feeding Hills.

The Six Flags New England amusement park is located in Agawam, on the banks of the Connecticut River.

Agawam's ZIP code of 01001 is the lowest number in the continental United States (not counting codes used for specific government buildings such as the IRS).[4]

Etymology

The Native American village originally sited on the west bank of the Connecticut River was known as Agawam, or Agawanus, Aggawom, Agawom, Onkowam, Igwam, and Auguam. It is variously speculated to mean "unloading place" and "fishcuring place", perhaps in reference to fish at Agawam Falls being unloaded from canoes for curing on the flats at the mouth of the Westfield River.[5]

Ipswich, Massachusetts was also known as Agawam during much of the 17th century, after the English name for the Agawam tribe of northeastern Massachusetts.

History

On May 15, 1636, William Pynchon purchased land on both sides of the Connecticut River from the local Pocomtuc Indians known as Agawam, which included present-day Springfield, Chicopee, Longmeadow, and West Springfield, Massachusetts. The purchase price for the Agawam portion was 10 coats, 10 hoes, 10 hatchets, 10 knives, and 10 fathoms of wampum. Agawam and West Springfield separated from Springfield to become the parish of Springfield in 1757; Agawam and West Springfield split in 1800. Agawam incorporated as a town on May 17, 1855.

In 1771, John Porter moved to Agawam and founded a gin distillery nine years later. After he died, his grandson, Harry, continued to work the business as the H. Porter Distilling Company. The plant was sold in 1917, and during Prohibition, the main products produced in the building were potato chips and cider. After the Volstead Act was repealed, the mill began producing gin again but closed permanently in 1938. The building, on Main Street near River Road, served as Agawam’s Department of Public Works garage until it fell into disrepair.

Agawam furnished 172 men who fought in the American Civil War, 22 of whom died in battle or of disease.

The original town hall, built in 1874 at the corner of Main and School Streets, housed the town government divisions as the current one does today, as well as the original town library located in the building’s Tower Room. A small school building was located near the premises and held grades one through three. The building was demolished in 1938, and the property is now the site of Benjamin Phelps Elementary School.[5]

The Feeding Hills town hall, built in 1906, was almost identical to the Agawam town hall and was located at the corner of Springfield and South Westfield Streets. The building was demolished in 1950, and the Clifford M. Granger Elementary School now occupies that land.[5]

May 29, 1930 and June 1, 1931 saw "grand openings" of Bowles Agawam Airport with the latter date including a visit from 100 biplanes of the United States Army Air Corps Eastern Air Arm.[6] A scheduled air service operated out of Bowles for approximately one year, before ending. The airport continued to operate as a civil airport until circa 1985. A pari-mutuel horse racing track, including grandstand and stables, was built adjacent to Bowles Airport. Seabiscuit won the Springfield Handicap at Agawam in track record time in October 1935.[7] The racetrack operated until pari-mutuel betting was outlawed by referendum in Hampden County in November 1938.[6] The airport also had plans in the early 1960s to become a commercial airport and host airlines for the city of Springfield, but plans were shelved. The airport and racetrack were demolished in the late 1980s and the area is now an industrial park.[5][6]

Geography

Agawam is located at 42°4′19″N 72°38′39″W / 42.07194°N 72.64417°W (42.071961, -72.644097).[8] The city borders West Springfield, Massachusetts, to the north, Southwick, Massachusetts, to the west, Longmeadow, Massachusetts, to the east, Springfield, Massachusetts, to the northeast, and Suffield, Connecticut, to the south. Westfield, Massachusetts, also borders to the northwest.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 24.2 square miles (63 km2) of which 23.2 square miles (60 km2) is land and 1 square mile (3 km2) (4.09%) is water.

The highest point in Agawam is the 640-foot (195 m)-tall Provin Mountain, a ridge that, along with the southern part of East Mountain, forms the western boundary of the city. Both are traversed by the Metacomet-Monadnock Trail and are part of the Metacomet Ridge, a mountainous trap rock ridgeline that stretches from Long Island Sound to nearly the Vermont border.

Agawam has a subsection known as Feeding Hills that runs along the border of Southwick and Westfield, Massachusetts, and Suffield, Connecticut. Its border with Agawam was mainly determined by Line Street, and its ZIP code is 01030.

Demographics

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1860 | 1,698 | — |

| 1870 | 2,001 | +17.8% |

| 1880 | 2,216 | +10.7% |

| 1890 | 2,352 | +6.1% |

| 1900 | 2,536 | +7.8% |

| 1910 | 3,501 | +38.1% |

| 1920 | 5,023 | +43.5% |

| 1930 | 7,095 | +41.3% |

| 1940 | 7,842 | +10.5% |

| 1950 | 10,166 | +29.6% |

| 1960 | 15,718 | +54.6% |

| 1970 | 21,717 | +38.2% |

| 1980 | 26,271 | +21.0% |

| 1990 | 27,323 | +4.0% |

| 2000 | 28,144 | +3.0% |

| 2010 | 28,438 | +1.0% |

| 2014 | 28,772 | +1.2% |

| * = population estimate. Source: United States Census records and Population Estimates Program data.[9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17] Source: | ||

As of the census[19] of 2010, there were 28,144 people, 11,260 households, and 7,462 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,210.9 people per square mile (467.6/km²). There were 11,659 housing units at an average density of 501.6 per square mile (193.7/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 96.71% White, 0.91% African American, 0.17% Native American, 0.98% Asian, 0.01% Pacific Islander, 0.43% from other races, and 0.80% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.83% of the population.

There were 11,260 households out of which 28.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 53.4% were married couples living together, 9.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 33.7% were non-families. 28.0% of all households were made up of individuals and 11.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.43 and the average family size was 3.01.

In the city, the population was spread out with 22.1% under the age of 18, 6.5% from 18 to 24, 29.7% from 25 to 44, 25.1% from 45 to 64, and 16.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 40 years. For every 100 females there were 90.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 86.9 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $49,390, and the median income for a family was $59,088. Males had a median income of $40,924 versus $30,428 for females. The per capita income for the city was $22,562. About 4.3% of families and 5.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 6.7% of those under age 18 and 7.5% of those age 65 or over.[20]

Government

Agawam is one of fourteen Massachusetts municipalities that have applied for, and been granted, city forms of government but wish to retain "The town of" in their official names.[21] A mayor is the elected leader of the city. The city council consists of eleven members elected at large by the voters and is the legislative branch of the town government.

The current mayor of Agawam is Richard A. Cohen[22]

Agawam is in the Massachusetts 2nd Congressional District and the First Hampden and Hampshire Senate district.

| Voter Registration and Party Enrollment as of October 15, 2008[23] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Number of Voters | Percentage | |||

| Democratic | 6,259 | 30.88% | |||

| Republican | 3,161 | 15.60% | |||

| Unaffiliated | 10,697 | 52.78% | |||

| Minor Parties | 152 | 0.75% | |||

| Total | 20,269 | 100% | |||

Historical commercial operations

1801 - E. Porter Peppermint distillery, later to become the "Agawam Gin" distillery.

1810 - A cotton mill was erected on the site of present-day Six Flags New England.

1812 - Agawam Woolen Mill was established on Elm Street. After a fire, the building was rebuilt in brick in 1889 and still exists. The Agawam Woolen Company folded in 1949.

Six Flags New England, formerly Riverside Amusement Park, began as a picnic grove as early as 1840. It became a full-fledged amusement park in 1940. Riverside Park Speedway, a NASCAR racing track, was part of Riverside park from 1948 to 2000. Riverside was sold to Six Flags in 1996.

1952 - Stacy Machine Co, came to a new plant located on Main St, is best known for producing specialized printing presses. Later known as Kidder-Stacy, the plant closed in the 1990s, but the Main St plant still stands.

1953 - WWLP an NBC affiliate television station began operation with studios and transmitting facilities on Provin Mountain in Feeding Hills.

Library

The Agawam Free Public Library was established in 1891.[24][25] The first libraries were rooms in the Agawam and Feeding Hills town halls and the Mittenague School in North Agawam. After a 1904 fire destroyed the Mittenague School and all the books in it, Fred P. Halladay donated land and buildings in North Agawam to use as a library. In 1925, Minerva Porter Davis donated a building in Agawam Center to serve as the library in that section of town, replacing the Agawam Town Hall rooms.[26] The Feeding Hills branch moved to a building across the street from the Feeding Hills town hall when that structure was removed to make way for Granger school. In 1978 the libraries were consolidated in a new building adjacent to the High School on Cooper St.

In fiscal year 2008, the city of Agawam spent 1.39% ($923,113) of its budget on its public library—some $32 per person.[27]

Education

- Benjamin J. Phelps Elementary School – has a "Tempis Fugit" sundial on the auditorium facing south

- Clifford M. Granger Elementary School

- James Clark Elementary School

- Robinson Park Elementary School

- Phelps Elementary School

- Roberta G. Doering Middle School – built in 1929, was first used as the High School, then as the Junior High, now a Middle School

- Agawam Junior High School – built in 1973

- Agawam High School – built in 1955

Points of interest

- The Agawam Historical Association operates the Agawam Historical and Fire House Museum at 35 Elm Street and the historic Thomas Smith House at 251 North West Street in Feeding Hills.

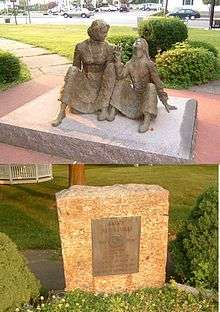

- Anne Sullivan Memorial - marker and statue dedicated to Helen Keller's "Teacher", born in Feeding Hills. The memorial is on the corner of Springfield and South Westfield Streets.

- The Massachusetts Veteran's Memorial Cemetery is located off Main Street.[28]

- A series of plaques with the names of Agawam citizens who died in the Vietnam War, World War II, World War I, the Revolutionary War, or the Spanish–American War is displayed at Benjamin J. Phelps Elementary School.

- The 110 mile Metacomet-Monadnock Trail (a hiking trail) traverses the ridgeline of Provin Mountain in western Agawam.

- Robinson State Park, a narrow, urban 852-acre (3.45 km2) park, has its entrance on North St.

- Six Flags New England, the largest amusement park in New England, is located in Agawam.

Notable people

- Creighton Abrams, who commanded military operations in the Vietnam War.[29]

- Daxe Rexford, lead guitarist for Pajama Slave Dancers.[30]

- Anne Sullivan, tutor of Helen Keller[31]

References

- ↑ Constantine, Sandra. "Agawam Mayor Richard Cohen seeks to fend off former state Rep. Rosemary Sandlin so he can win 6th term". MassLive. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

Cohen, a Democrat, has painted himself as a fiscal conservative who always comes up balanced budgets with little fat for the City Council to trim.

- ↑ "Office of the Mayor". Town of Agawam, Massachusetts. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- ↑ Although it is called the "Town of Agawam," it is a statutory city of Massachusetts. See Office of the Secretary of the Commonwealth.

- ↑ "United States Postal Service Facts". United States Postal Service. Archived from the original on 25 March 2010. Retrieved 2010-03-13.

- 1 2 3 4 Agawam Centennial Committee (June 1955). Agawam, Massachusetts Over the Span of a Century. Agawam Centennial Committee. pp. 9–11.

- 1 2 3 Freeman, Paul (24 December 2014)."Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields: Western Massachusetts, Bowles Agawam Airfield" Accessed 11 June 2015.

- ↑ "Seabiscuit, 1938 Horse of the Year". www.spiletta.com. Accessed 11 June 2015.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ "TOTAL POPULATION (P1), 2010 Census Summary File 1, All County Subdivisions within Massachusetts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 13, 2011.

- ↑ "Massachusetts by Place and County Subdivision - GCT-T1. Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ↑ "1990 Census of Population, General Population Characteristics: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1990. Table 76: General Characteristics of Persons, Households, and Families: 1990. 1990 CP-1-23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ↑ "1980 Census of the Population, Number of Inhabitants: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1981. Table 4. Populations of County Subdivisions: 1960 to 1980. PC80-1-A23. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ↑ "1950 Census of Population" (PDF). 1: Number of Inhabitants. Bureau of the Census. 1952. Section 6, Pages 21-10 and 21-11, Massachusetts Table 6. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1930 to 1950. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ↑ "1920 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. Number of Inhabitants, by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions. Pages 21-5 through 21-7. Massachusetts Table 2. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1920, 1910, and 1920. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ↑ "1890 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. Pages 179 through 182. Massachusetts Table 5. Population of States and Territories by Minor Civil Divisions: 1880 and 1890. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ↑ "1870 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1872. Pages 217 through 220. Table IX. Population of Minor Civil Divisions, &c. Massachusetts. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ↑ "1860 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1864. Pages 220 through 226. State of Massachusetts Table No. 3. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "Massachusetts DHCD" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 February 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-25.

- ↑ http://www.sec.state.ma.us/cis/cisctlist/ctlistalph.htm

- ↑ "Town of Agawam, MA Mayor". Archived from the original on 12 December 2010. Retrieved December 2010.

- ↑ "Registration and Party Enrollment Statistics as of October 15, 2008" (PDF). Massachusetts Elections Division. Retrieved 2010-05-08.

- ↑ Report of the Free Public Library Commission of Massachusetts. v.9 (1899)

- ↑ "Agawam Public Library". agawamlibrary.org. Retrieved 2010-11-09.

- ↑ Agawam Centennial Committee (June 1955). Agawam, Massachusetts Over the Span of a Century. Agawam Centennial Committee. pp. 16–17.

- ↑ July 1, 2007 through June 30, 2008; cf. The FY2008 Municipal Pie: What’s Your Share? Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Board of Library Commissioners. Boston: 2009. Available: Municipal Pie Reports. Retrieved 2010-08-04

- ↑ http://www.memorialpath.org/

- ↑ Wilson, George C. (1974-09-05). "Creighton Abrams: From Agawam to Chief of Staff". Washington Post. Section D, p. 4.

- ↑ "PAJAMA SLAVE DANCERS, DAMMIT!". snakefoot.com. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ↑ "Perkins - Anne Sullivan". Perkins School. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Agawam, Massachusetts. |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||