Agape feast

The term Agape or Love feast was used for certain religious meals among early Christians that seem to have been originally closely related to the Eucharist.[2] In modern times the Lovefeast is used to refer to a Christian ritual meal distinct from the Eucharist.[2]

References to such communal meals are discerned in 1 Corinthians 11:17–34, in Saint Ignatius of Antioch's Letter to the Smyrnaeans, where the term "agape" is used, and in a letter from Pliny the Younger to Trajan,[3] in which he reported that the Christians, after having met "on a stated day" in the early morning to "address a form of prayer to Christ, as to a divinity", later in the day would "reassemble, to eat in common a harmless meal".[2] Similar communal meals are attested also in the "Apostolic Tradition" often attributed to Hippolytus of Rome, who does not use the term "agape", and by Tertullian, who does. The connection between such substantial meals and the Eucharist had virtually ceased by the time of Cyprian (died 258), when the Eucharist was celebrated with fasting in the morning and the agape in the evening.[2] The Synod of Gangra in 340 makes mention of them in relation to a heretic who had barred his followers from attending them.[4]The Council of Laodicea of about 363–64 forbade the use of churches for celebrating the Agape or love feast.[5] Though still mentioned in the Quinisext Council of 692, the Agape fell into disuse soon after, except perhaps in Ethiopia.[2]

A form of meal referred to as Agape feast or Lovefeast was introduced among certain eighteenth-century Pietist groups, such as the Schwarzenau Brethren and the Moravian Church, and was adopted by Methodism. The name has been revived more recently among other groups, including Anglicans,[2] as well as the American "House Church" movement.[6]

Early Christianity

The earliest reference to a meal of the type referred to as "agape" is in Paul the Apostle's First Epistle to the Corinthians, although the term can only be inferred vaguely from its prominence in 1 Cor 13. Many New Testament scholars hold that the Christians of Corinth met in the evening and had a common meal including sacramental action over bread and wine.[7] 1 Corinthians 11:20–34 indicates that the rite was associated with participation in a meal of a more general character.[8] It apparently involved a full meal, with the participants bringing their own food but eating in a common room. Perhaps predictably enough, it could at times deteriorate into merely an occasion for eating and drinking, or for ostentatious displays by the wealthier members of the community, as happened in Corinth, drawing the criticisms of Paul: "I hear that when you come together as a church, there are divisions among you, and to some extent I believe it. No doubt there have to be differences among you to show which of you have God's approval. When you come together, it is not the Lord's Supper you eat, for as you eat, each of you goes ahead without waiting for anybody else. One remains hungry, another gets drunk. Don't you have homes to eat and drink in? Or do you despise the church of God and humiliate those who have nothing?"[9]

The term "Agape" is also used in reference to meals in Jude 12 and according to a few manuscripts of 2 Peter 2:13

Soon after the year 100, Ignatius of Antioch refers to the agape or love-feast.[10] In Letter 97 to Trajan, Pliny the Younger perhaps indicates, in about 112, that such a meal was normally taken separately from the Eucharistic celebration (although he is silent about its nomenclature): he speaks of the Christians separating after having offered prayer, on the morning of a fixed day, to Christ as God, and reassembling later for a common meal.[11] The rescheduling of the agape meal was triggered by Corinthian selfishness and gluttony.[12] Tertullian too seems to write of these meals,[13][14] though what he describes is not quite clear.[2]

Clement of Alexandria (c. 150–211/216) distinguished so-called "Agape" meals of luxurious character from the agape (love) "which the food that comes from Christ shows that we ought to partake of".[15] Accusations of gross indecency were sometimes made against the form that these meals sometimes took.[16] Referring to Clement of Alexandria, Stromata III,2, Philip Schaff commented: "The early disappearance of the Christian agapæ may probably be attributed to the terrible abuse of the word here referred to, by the licentious Carpocratians. The genuine agapæ were of apostolic origin (2 Pet. ii. 13; Jude 12), but were often abused by hypocrites, even under the apostolic eye (1 Corinthians 11:21). In the Gallican Church, a survival or relic of these feasts of charity is seen in the pain béni; and, in the Eastern Orthodox Church in the ἀντίδωρον (antidoron) or eulogiæ, also known as prosphora distributed to non-communicants at the close of the Divine Liturgy (Eucharist), from the loaf out of which the Lamb (Host) and other portions have been cut during the Liturgy of Preparation."[17]

Augustine of Hippo also objected to the continuance in his native North Africa of the custom of such meals, in which some indulged to the point of drunkenness, and he distinguished them from proper celebration of the Eucharist: "Let us take the body of Christ in communion with those with whom we are forbidden to eat even the bread which sustains our bodies."[18] He reports that even before the time of his stay in Milan, the custom had already been forbidden there.[19]

Canons 27 and 28 of the Council of Laodicea (364) restricted the abuses of taking home part of the provisions and of holding the meals in churches.[20] The Third Council of Carthage (393) and the Second Council of Orléans (541)[lower-alpha 2] reiterated the prohibition of feasting in churches, and the Trullan Council of 692 decreed that honey and milk were not to be offered on the altar (Canon 57), and that those who held love feasts in churches should be excommunicated (Canon 74).

Medieval Georgia

In the medieval Georgian Orthodox Church, the term agapi referred to a commemorative meal or distribution of victuals, offered to clergymen, the poor, or passers-by, accompanying the funeral service on the anniversary of the deceased. The permanent celebration of agapae was assured by legacies and foundations.[24]

Protestant revivals of the practice

After the Protestant Reformation there was a move amongst some groups of Christians to try to return to the practices of the New Testament Church. One such group was the Schwarzenau Brethren (1708) who counted a Love Feast consisting of Feet-washing, the Agape meal, and the Eucharist among their "outward yet sacred" ordinances. Another was the Moravians led by Count Zinzendorf who adopted a form consisting of a simple sharing of a simple meal, and then testimonies or a devotional address were given and letters from missionaries read.

John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, travelled to America in the company of the Moravians and greatly admired their faith and practice. After his conversion in 1738 he introduced the Love Feast to what became known as the Methodist movement. Due to the lack of ordained ministers within Methodism, the Love Feast took on a life of its own, as there were few opportunities to take Communion. As such, the Primitive Methodists celebrated the Love Feast, before it gradually died out again in the nineteenth century as the revival cooled.

Contemporary

The Schwarzenau Brethren groups (the largest being the Church of the Brethren) regularly practice Agape feasts (called "Love Feast"), which include feetwashing, a supper, and communion, with hymns and brief scriptural meditations interspersed throughout the worship service. The Creation Seventh Day Adventists partake of an Agape feast as a part of their New Moon observances, taking the form of a formal, all-natural meal held after the communion supper. The Agape is a common feature used by the Catholic Neocatechumenal Way in which members of the Way participate in light feast after the celebration of the Eucharist on certain occasions.

A number of Eastern Orthodox Christian parishes will have an agape meal on Sundays and feast days following the Divine Liturgy, and especially at the conclusion of the Paschal Vigil.

Notes

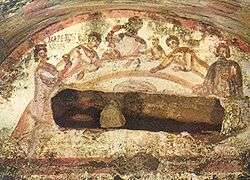

- ↑ The word "Agape" in the inscription has led some to interpret the scene as that of an Agape feast. However, the phrase within which the word appears is "Agape misce nobis" (Agape, mix for us, i.e. prepare the wine for us), making it more likely that Agape is the name of the woman holding the cup. A very similar fresco and inscription elsewhere in the same catacomb has, in exactly the same position within the fresco, the words "Misce mi Irene" (Mix for me, Irene). A reproduction of this other fresco can be seen at Catacombe dei Ss. Marcellino e Pietro,[1] where it is accompanied by the explanation (in Italian) "One of the most frequently recurring scenes in the paintings is that of the banquet, generally interpreted as a symbolic representation of the joys of the afterlife, but in which it may be possible to discern a realistic presentation of the agapae, the funeral banquets held to commemorate the dead person." An article by Carlo Carletti on L'Osservatore Romano of 1 November 2009 recalls that the same catacomb has in fact a whole series of similar frescos of banquets with men reclining at a banquet and calling on a maid to serve them wine. The names Agape and Irene were common among slaves and freedwomen at the time, but the fact that these particular names recur twelve times in the catacomb suggests that they were chosen not just as names for the maids but to evoke the ideas that the two names signify: Love and Peace.

- ↑ Several sources mention a prohibition of the Agape by the Second Council of Orleans in AD 541.[21][22][23] More numerous are the sources (which do not speak of the Agape) that put the Second Council of Orleans in AD 533.

References

- ↑ "Catacombe", Storia [History] (in Italian), IT.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "agape", Dictionary of the Christian Church (article), Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3.

- ↑ Pliny, To Trajan, Book 10, Letter 97.

- ↑ http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf214.viii.v.iv.xi.html

- ↑ "Synod of Laodicea", Fathers, New Advent, canon 28.

- ↑ Supper, Sanctification.

- ↑ Welker, Michael, What happens in Holy Communion?, pp. 75–76

- ↑ "Agape", NET (dictionary), Bible.

- ↑ 1 Corinthians 11:17–34

- ↑ of Antioch, Ignatius, Smyrnaeans, Early Christian writings, 8:2.

- ↑ "They met on a stated day before it was light, and addressed a form of prayer to Christ, as to a divinity, binding themselves by a solemn oath, not for the purposes of any wicked design, but never to commit any fraud, theft, or adultery, never to falsify their word, nor deny a trust when they should be called upon to deliver it up; after which it was their custom to separate, and then reassemble, to eat in common a harmless meal".

- ↑ Davies, JG (1965), The Early Christian Church, Holt Rinehart Winston, p. 61.

- ↑ Schaff (ed.), Apology, CCEL, 39.

- ↑ Tertulian, De Corona Militis, 3.

- ↑ "Paedagogus", Fathers, New advent, II, 1.

- ↑ Tertullian, De Jejuniis, 17,

Sed majoris est Agape, quia per hanc adolescentes tui cum sororibus dormiunt, appendices scilicet gulae lascivia et luxuria

, quoted in Gibbons, Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. - ↑ Schaff (ed.), Elucidations, CCEL.

- ↑ "Letter", Letter 22 (A.D. 392), New advent, 22, 1:3.

- ↑ Confessions, U Penn, 6.2.2.

- ↑ "The Synod of Laodicea", Fathers, New advent.

- ↑ The Gospel Advocate 3, 1823.

- ↑ Cole, Richard Lee, Love-feasts: A History of the Christian Agape.

- ↑ The Antiquaries Journal, Oxford University Press, 1975.

- ↑ Toumanoff, Cyril (1949–51). "The Fifteenth-Century Bagratids and the Institution of Collegial Sovereignty in Georgia". Traditio 7: 175.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Agape feast. |

- Catholic Encyclopedia, New advent.

- Agape, Latter Rain Ministry.

- Sermon, Seekers Church, 2000-02-27.

- Love Feast (Links), UK: Vote for Jesus.