Hirschsprung's disease

| Hirschsprung's disease | |

|---|---|

Histopathology of Hirschsprung disease. Enzyme histochemistry showing aberrant acetylcholine esterase (AchE)-positive nerve fibers (brown) in the lamina propria mucosae. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | medical genetics |

| ICD-10 | Q43.1 |

| ICD-9-CM | 751.3 |

| OMIM | 142623 |

| DiseasesDB | 5901 |

| MedlinePlus | 001140 |

| eMedicine | med/1016 |

| MeSH | D006627 |

Hirschsprung's disease or Hirschsprung disease (HD), also called congenital megacolon or congenital aganglionic megacolon, is a form of megacolon that occurs when part or all of the large intestine or antecedent parts of the gastrointestinal tract have no ganglion cells and therefore cannot function. During normal prenatal development, cells from the neural crest migrate into the large intestine (colon) to form the networks of nerves called the myenteric plexus (Auerbach plexus) (between the smooth muscle layers of the gastrointestinal tract wall) and the submucosal plexus (Meissner plexus) (within the submucosa of the gastrointestinal tract wall). In Hirschsprung's disease, the migration is not complete and part of the colon lacks these nerve bodies that regulate the activity of the colon. The affected segment of the colon cannot relax and pass stool through the colon, creating an obstruction.[1] In most affected people, the disorder affects the part of the colon that is nearest the anus. In rare cases, the lack of nerve bodies involves more of the colon. In five percent of cases, the entire colon is affected. Stomach and esophagus may be affected too.

Hirschsprung's disease occurs in about one in 5,000 of live births.[2] It is usually diagnosed in children, and affects boys more often than girls. About 10% of cases are familial.

Signs and symptoms

Typically, Hirschsprung's disease is diagnosed shortly after birth, although it may develop well into adulthood, because of the presence of megacolon, or because the baby fails to pass the first stool (meconium)[3] within 48 hours of delivery. Normally, 90% of babies pass their first meconium within 24 hours, and 99% within 48 hours. Other symptoms include green or brown vomit, explosive stools after a doctor inserts a finger into the rectum, swelling of the abdomen, lots of gas and bloody diarrhea.

Some cases are diagnosed later, into childhood, but usually before age 10.[3] The child may experience fecal retention, constipation, or abdominal distention.[3] With an incidence of one in 5,000 births, the most cited feature is absence of ganglion cells: notably in males, 75 percent have none in the end of the colon (recto-sigmoid) and eight percent lack ganglion cells in the entire colon. The enlarged section of the bowel is found proximally, while the narrowed, aganglionic section is found distally, closer to the end of the bowel. The absence of ganglion cells results in a persistent over-stimulation of nerves in the affected region, resulting in contraction.

Some, extremely rare cases, the absence of ganglion cells continues to spread after the corrective surgery, resulting in multiple surgeries.

Those patients that also have thyroid cancer, may be able to digest food properly, but may not be able to use the nutrients properly.

Pathophysiology

The most accepted theory of the cause of Hirschsprung is that there is a defect in the craniocaudal migration of neuroblasts originating from the neural crest that occurs during the first 12 weeks of gestation. Defects in the differentiation of neuroblasts into ganglion cells and accelerated ganglion cell destruction within the intestine may also contribute to the disorder.[4]

This lack of ganglion cells in the myenteric and submucosal plexus is well-documented in Hirschsprung's disease.[3] With Hirschsprung's disease, the segment lacking neurons (aganglionic) becomes constricted, causing the normal, proximal section of bowel to become distended with feces. This narrowing of the distal colon and the failure of relaxation in the aganglionic segment are thought to be caused by the lack of neurons containing nitric oxide synthase.[3]

The equivalent disease in horses is Lethal white syndrome.[5]

Genetic basis

Several genes and specific regions on chromosomes (loci) have been shown or suggested to be associated with Hirschsprung's disease:

| Type | OMIM | Gene | Locus |

|---|---|---|---|

| HSCR1 | 142623 | RET | 10q11.2 |

| HSCR2 | 600155 | EDNRB | 13q22 |

| HSCR3 | 600837 | GDNF | 5p13.1-p12 |

| HSCR4 | 131242 | EDN3 | 20q13.2-q13.3 |

| HSCR5 | 600156 | ? | 21q22 |

| HSCR6 | 606874 | ? | 3p21 |

| HSCR7 | 606875 | ? | 19q12 |

| HSCR8 | 608462 | ? | 16q23 |

| HSCR9 | 611644 | ? | 4q31-32 |

| — | 602229 | SOX10 | 22q13 |

| — | 600423 | ECE1 | 1p36.1 |

| — | 602018 | NRTN | 19p13.3 |

| — | 602595 | SIP1 | 14q13-q21 |

| — | 191315 | NTRK1 | 1q23.1 |

| — | 605802 | ZEB2 | 2q22.3 |

Hirschsprung's disease can also present as part of a multisystem disorder, such as Down syndrome, Bardet-Biedl syndrome, Waardenburg-Shah syndrome, Mowat-Wilson syndrome, Goldberg-Shpritzen megacolon syndrome, cartilage-hair hypoplasia, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 and congenital central hypoventilation syndrome.[6]

The RET proto-oncogene accounts for the highest proportion of both familial and sporadic cases, with a wide range of mutations scattered along its entire coding region.[7] A proto-oncogene is a gene that can cause cancer if it is mutated or over-expressed.

Research published in 2002 suggested that Hirschsprung's may be caused by the interaction between two proteins encoded by two variant genes. The RET proto-oncogene on chromosome 10 was identified as one of the two genes involved. The other protein that RET must interact with in order to cause Hirschsprung’s disease is termed EDNRB, and is encoded by the gene EDNRB located on chromosome 13.

Hirschsprung's disease, hypoganglionosis, gut dysmotility, gut transit disorders and intussusception have been recorded with the dominantly inherited neurovisceral porphyrias (acute intermittent porphyria, hereditary coproporphyria, variegate porphyria). Children may require enzyme or DNA testing for these disorders as they may not produce or excrete porphyrins prepuberty.

RET proto-oncogene

RET is a gene that codes for proteins that assist cells of the neural crest in their movement through the digestive tract during the development of the embryo. Those neural crest cells eventually form bundles of nerve cells called ganglions. EDNRB codes for proteins that connect these nerve cells to the digestive tract. Thus, mutations in these two genes could directly lead to the absence of certain nerve fibers in the colon. Research published in June 2004 suggests that there are several genes associated with Hirschsprung’s disease.[8] Also, new research suggests that mutations in genomic sequences involved in regulating EDNRB have a bigger impact on Hirschsprung’s disease than previously thought.

RET can mutate in many ways and is associated with Down syndrome. Since Down Syndrome is comorbid in two percent of Hirschsprung’s cases, there is a likelihood that RET is involved heavily in both Hirschprung's disease and Down Syndrome. RET is also associated with medullary thyroid cancer anf neuroblastoma, which is a type of cancer common in children. Both of these disorders are more common in Hirschsprung’s patients than in the general population. One function that RET controls is the travel of the neural crest cells through the intestines in the developing fetus. The earlier the RET mutation occurs in Hirschsprung’s disease, the more severe the disorder becomes.

Other genes

Common and rare DNA variations in the Neuregulin 1 (NRG1) and NRG3 (NRG3) were first shown to be associated with the disease in Chinese patients through a Genome Wide Association Study (GWAS) by the Hong Kong team in 2009 [9] and 2012 respectively[10] Subsequent studies in both Asian and Caucasian patients confirmed the initial findings by the University of Hong Kong. Both rare and common variants in these two genes have been identified in additional Chinese,[11] Thai, Korean, Indonesian and Spanish patients. These two genes are known to play a role in the formation of the enteric nervous system, thus, they are likely to be involved in the pathology of Hirschsprung, at least in some cases.

Diagnosis

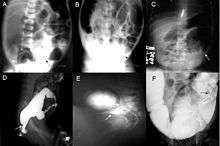

Definitive diagnosis is made by suction biopsy of the distally narrowed segment.[12] A histologic examination of the tissue would show a lack of ganglionic nerve cells. Diagnostic techniques involve anorectal manometry,[13] barium enema, and rectal biopsy. The suction rectal biopsy is considered the current international gold standard in the diagnosis of Hirschsprung's disease.[14]

Radiologic findings may also assist with diagnosis.[15] Cineanography (fluoroscopy of contrast medium passing anorectal region) assists in determining the level of the affected intestines.

Treatment

Treatment of Hirschsprung's disease consists of surgical removal (resection) of the abnormal section of the colon, followed by reanastomosis.

Colostomy

The first stage of treatment used to be a reversible colostomy. In this approach, the healthy end of the large intestine is cut and attached to an opening created on the front of the abdomen. The contents of the bowel are discharged through the hole in the abdomen and into a bag. Later, when the child’s weight, age, and condition are right, the "new" functional end of the bowel is connected with the anus. The first surgical treatment involving surgical resection followed by reanastomosis without a colostomy occurred as early as 1933 by Doctor Baird in Birmingham on a one-year-old boy.

Swenson, Soave, Duhamel, and Boley procedures

Orvar Swenson, who discovered the cause of Hirschsprung’s, first performed its surgical treatment, the pull-through surgery in 1948.[16] The pull-through procedure repairs the colon by connecting the functioning portion of the bowel to the anus. The pull-through procedure is the typical method for treating Hirschsprung’s in younger patients. Swenson devised the original procedure, and the pull-through surgery has been modified many times.

Currently, there are several different surgical approaches, which include the Swenson, Soave, Duhamel, and Boley procedures. The Swenson procedure leaves a small portion of the diseased bowel. The Soave procedure leaves the outer wall of the colon unaltered. The Boley procedure is a small modification of the Soave procedure, so the term "Soave-Boley" procedure is sometimes used.[17][18] The Duhamel procedure uses a surgical stapler to connect the good and bad bowel.

For the 15 percent of children who do not obtain full bowel control, other treatments are available. Constipation may be remedied by laxatives or a high fiber diet. In those patients, serious dehydration can play a major factor in their lifestyle. A lack of bowel control may be addressed by a stoma, similar to a colostomy. The Malone antegrade colonic enema (ACE) is also an option.[19] In a Malone ACE, a tube goes through the abdominal wall to the appendix or, if available, to the colon. The bowel is then flushed daily.[20] Children as young as 6 years of age may administer this daily flush on their own.

If the affected portion of the lower intestine is restricted to the lower portion of the rectum, other surgical procedures may be performed, such as a posterior rectal myectomy.

The prognosis is good in 70 percent of cases. Chronic post-operative constipation is present in 7 to 8 percent of the operated cases. Post-operative enterocolitis is a severe manifestation that is present in the 10%–20% of operated patients.

Associated syndromes

- Bardet-Biedl syndrome

- Cartilage-hair hypoplasia[21]

- Congenital central hypoventilation syndrome[22]

- MEN2[23]

- Mowat-Wilson syndrome[24]

- Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome[25]

- Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) [26]

- Waardenburg syndrome

Epidemiology

According to a 1984 study conducted in Maryland, Hirschsprung's disease appears on 18.6 per 100,000 live births.[27] In Japan, Hirschsprung disease occurs at a similar rate of about one in 5,000 births (20 per 100,000).[28] It is more common in male rather than female (4.32:1) and in white rather than non-white.[29] Nine percent of the Hirschsprung cases were also diagnosed as having Down syndrome.[27] Most cases are diagnosed before the patient is 10 years of age.[3]

History

The first report of Hirschsprung disease dates back to 1691,[30] however, the disease is named after Harald Hirschsprung, the Danish physician who first described two infants who died of this disorder in 1888.[31][32]

Hirschsprung’s disease is a congenital disorder of the colon in which certain nerve cells, known as ganglion cells, are absent, causing chronic constipation.[33] The lack of ganglion cells is in the myenteric plexus (Auerbach's Plexus), which is responsible for moving food in the intestine. A barium enema is the mainstay of diagnosis of Hirschsprung’s, though a rectal biopsy showing the lack of ganglion cells is the only certain method of diagnosis.

The first publication on an important genetic discovery of the disease was from Martucciello Giuseppe et al. in 1992. The authors described a case of a patient with total colonic aganglionosis associated with a 46, XX, del 10 (q11.21 q21.2) karyotype.[34] The major gene of Hirschsprung disease was identified in this chromosomal 10 region, it was the RET proto-oncogene.[35]

The usual treatment is "pull-through" surgery where the portion of the colon that does have nerve cells is pulled through and sewn over the part that lacks nerve cells (National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse). For a long time, Hirschsprung’s was considered a multi-factorial disorder, where a combination of nature and nurture were considered to be the cause. However, in August 1993, two articles by independent groups in Nature Genetics said that Hirschsprung’s disease could be mapped to a stretch of chromosome 10.[36][37]

This research also suggested that a single gene was responsible for the disorder. However, the researchers were unable to isolate it.

See also

- Achalasia

- Ileus, failure of peristaltic muscle activity in the gut

- Intestinal neuronal dysplasia

- Neonatal intensive care (NICU)

References

- ↑ Parisi MA; Pagon, RA; Bird, TD; Dolan, CR; Stephens, K; Adam, MP (2002). Pagon RA, Bird TC, Dolan CR, Stephens K, ed. "Hirschsprung Disease Overview". GeneReviews. PMID 20301612.

- ↑ Samuel Nurko MD, MPH- Director Center for Motility and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders, Children’s Hospital, Boston. "HIRSCHSPRUNG'S DISEASE" (PDF). Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Goldman, Lee. Goldman's Cecil Medicine (24th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders. p. 867. ISBN 1437727883.

- ↑ Kays DW (1996). "Surgical conditions of the neonatal intestinal tract". Clinics in Perinatology 23 (2): 353–75. PMID 8780909.

- ↑ Metallinos DL, Bowling AT, Rine J (Jun 1998). "A missense mutation in the endothelin-B receptor gene is associated with Lethal White Foal Syndrome: an equine version of Hirschsprung disease". Mamm. Genome 9 (6): 426–31. doi:10.1007/s003359900790. PMID 9585428.

- ↑ Online 'Mendelian Inheritance in Man' (OMIM) 142623

- ↑ Martucciello G, Ceccherini I, Lerone M, Jasonni V (2000). "Pathogenesis of Hirschsprung's disease". Journal of Pediatric Surgery 35 (7): 1017–1025. doi:10.1053/jpsu.2000.7763. PMID 10917288.

- ↑ Puri P, Shinkai T (2004). "Pathogenesis of Hirschsprung's disease and its variants: recent progress". Semin. Pediatr. Surg. 13 (1): 18–24. doi:10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2003.09.004. PMID 14765367.

- ↑ Garcia-Barcelo, Maria-Merce (2009). "Genome-wide association study identifies NRG1 as a susceptibility locus for Hirschsprung's disease". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106: 2694–2699. doi:10.1073/pnas.0809630105. PMID 19196962.

- ↑ Tang, Clara (May 10, 2012). "Genome-wide copy number analysis uncovers a new HSCR gene: NRG3.". PLoS Genet. 8 (5): e1002687. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002687. PMID 22589734.

- ↑ Yang J, Duan S, Zhong R, Yin J, Pu J, Ke J, Lu X, Zou L, Zhang H, Zhu Z, Wang D, Xiao H, Guo A, Xia J, Miao X, Tang S, Wang G (2013). "Exome sequencing identified NRG3 as a novel susceptible gene of Hirschsprung's disease in a Chinese population". Mol. Neurobiol. 47 (3): 957–66. doi:10.1007/s12035-012-8392-4. PMID 23315268.

- ↑ Dobbins WO, Bill AH (1965). "Diagnosis of Hirschsprung's Disease Excluded by Rectal Suction Biopsy". New England Journal of Medicine 272 (19): 990–993. doi:10.1056/NEJM196505132721903. PMID 14279253.

- ↑ Eli Ehrenpreis (Oct 2003). Anal and rectal diseases explained. Remedica. pp. 15–. ISBN 978-1-901346-67-1. Retrieved 2010-11-12.

- ↑ Martucciello G, Pini Prato A, Puri P, Holschneider AM, Meier-Ruge W, Jasonni V, Tovar JA, Grosfeld JL (2005). "Controversies concerning diagnostic guidelines for anomalies of the enteric nervous system: a report from the fourth International Symposium on Hirschsprung's disease and related neurocristopathies". J Pediatr Surg. 40 (10): 1527–31. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.07.053. PMID 16226977.

- ↑ Kim HJ, Kim AY, Lee CW, Yu CS, Kim JS, Kim PN, Lee MG, Ha HK (2008). "Hirschsprung disease and hypoganglionosis in adults: radiologic findings and differentiation". Radiology 247 (2): 428–34. doi:10.1148/radiol.2472070182. PMID 18430875.

- ↑ Swenson O (1989). "My early experience with Hirschsprung's disease". J. Pediatr. Surg. 24 (8): 839–44; discussion 844–5. doi:10.1016/S0022-3468(89)80549-4. PMID 2671336.

- ↑ W. Allan Walker (2004-07-01). Pediatric gastrointestinal disease: pathophysiology, diagnosis, management. PMPH-USA. pp. 2120–. ISBN 978-1-55009-240-0. Retrieved 2010-11-12.

- ↑ Timothy R. Koch (2003). Colonic diseases. Humana Press. pp. 387–. ISBN 978-0-89603-961-2. Retrieved 2010-11-12.

- ↑ Malone PS, Ransley PG, Kiely EM (1990). "Preliminary report: the antegrade continence enema". Lancet 336 (8725): 1217–1218. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(90)92834-5. PMID 1978072.

- ↑ Walsh, Koyle, Waxman (2000). "The Malone ACE Procedure for Fecal Incontinence". Infections in Urology 13 (4).

- ↑ Mäkitie O, Heikkinen M, Kaitila I, Rintala R (2002). "Hirschsprung's disease in cartilage-hair hypoplasia has poor prognosis". J Pediatr Surg 37 (11): 1585–8. doi:10.1053/jpsu.2002.36189. PMID 12407544.

- ↑ de Pontual L, Pelet A, Clement-Ziza M, Trochet D, Antonarakis SE, Attie-Bitach T, Beales PL, Blouin JL, Dastot-Le Moal F, Dollfus H, Goossens M, Katsanis N, Touraine R, Feingold J, Munnich A, Lyonnet S, Amiel J (2007). "Epistatic interactions with a common hypomorphic RET allele in syndromic Hirschsprung disease". Human Mutation 28 (8): 790–6. doi:10.1002/humu.20517. PMID 17397038.

- ↑ Saunders CJ, Zhao W, Ardinger HH (2009). "Comprehensive ZEB2 gene analysis for Mowat-Wilson syndrome in a North American cohort: a suggested approach to molecular diagnostics". American Journal of Medical Genetics 149A (11): 2527–31. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.33067. PMID 19842203.

- ↑ Bonnard A, Zeidan S, Degas V, Viala J, Baumann C, Berrebi D, Perrusson O, El Ghoneimi A (2009). "Outcomes of Hirschsprung's disease associated with Mowat-Wilson syndrome". Journal of Pediatric Surgery 44 (3): 587–91. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.10.066. PMID 19302864.

- ↑ Mueller C, Patel S, Irons M, Antshel K, Salen G, Tint GS, Bay C (2003). "Normal cognition and behavior in a Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome patient who presented with Hirschsprung disease". American Journal of Medical Genetics 123A (1): 100–6. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.20491. PMC 1201564. PMID 14556255.

- ↑ Flori E, Girodon E, Samama B, Becmeur F, Viville B, Girard-Lemaire F, Doray B, Schluth C, Marcellin L, Boehm N, Goossens M, Pingault V (2005). "Trisomy 7 mosaicism, maternal uniparental heterodisomy 7 and Hirschsprung's disease in a child with Silver-Russell syndrome". European Journal of Human Genetics 13 (9): 1013–8. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201442. PMID 15915162.

- 1 2 Goldberg EL (1984). "An epidemiological study of Hirschsprung's disease". Int J Epidemiol 13 (4): 479–85. doi:10.1093/ije/13.4.479. PMID 6240474.

- ↑ Suita S, Taguchi T, Ieiri S, Nakatsuji T (2005). "Hirschsprung's disease in Japan: analysis of 3852 patients based on a nationwide survey in 30 years". Journal of Pediatric Surgery 40 (1): 197–201; discussion 201–2. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.09.052. PMID 15868585.

- ↑ Colwell, Janice (2004). Fecal and Urinary Diversion Management. Mosby. p. 264. ISBN 978-0-323-02248-4.

- ↑ Hirschsprung's Disease and Allied Disorders. Berlin: Springer. 2007. ISBN 3-540-33934-5.

- ↑ synd/1163 at Who Named It?

- ↑ Hirschsprung, H. (1888). "Stuhlträgheit Neugeborener in Folge von Dilatation und Hypertrophie des Colons". Jahrbuch für Kinderheilkunde und physische Erziehung (Berlin) 27: 1–7.

- ↑ Worman S, Ganiats TG (1995). "Hirschsprung's disease: a cause of chronic constipation in children". Am Fam Physician 51 (2): 487–94. PMID 7840044.

- ↑ Martucciello G, Bicocchi MP, Dodero P.,Lerone M.,Silengo Cirillo M, Puliti A, Gimelli G, Romeo G. (1992). "Total colonic aganglionosis associated with interstitial deletion of the long arm of chromosome 10". Pediatric Surgery International 7 (4): 308–310. doi:10.1007/BF00183991.

- ↑ Romeo G, Ronchetto P, Luo Y, Barone V, Seri M, Ceccherini I, Pasini B, Bocciardi R, Lerone M, Kääriäinen H (1994). "Point mutations affecting the tyrosine kinase domain of the RET proto-oncogene in Hirschsprung's disease". Nature 367 (6461): 377–378. doi:10.1038/367377a0. PMID 8114938.

- ↑ Angrist M, Kauffman E, Slaugenhaupt SA, Matise TC, Puffenberger EG, Washington SS, Lipson A, Cass DT, Reyna T, Weeks DE (1993). "A gene for Hirschsprung disease (megacolon) in the pericentromeric region of human chromosome 10". Nat. Genet. 4 (4): 351–6. doi:10.1038/ng0893-351. PMID 8401581.

- ↑ Lyonnet S, Bolino A, Pelet A, Abel L, Nihoul-Fékété C, Briard ML, Mok-Siu V, Kaariainen H, Martucciello G, Lerone M, Puliti A, Luo Y, Weissenbach J, Devoto M, Munnich A, Romeo G (1993). "A gene for Hirschsprung disease maps to the proximal long arm of chromosome 10". Nat. Genet. 4 (4): 346–50. doi:10.1038/ng0893-346. PMID 8401580.

External links

- CHAMPS Appeal Registered charity England and Wales 1150443

- Hirschsprung's disease at DMOZ

- The Bowel Movement

- Hirschsprung's & Motility Disorders Support Network

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||