Cheetah

| Cheetah Temporal range: Pleistocene - Holocene, 1.9–0 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| A South African cheetah (A. jubatus jubatus) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Felinae |

| Genus: | Acinonyx |

| Species: | A. jubatus |

| Binomial name | |

| Acinonyx jubatus (Schreber, 1775) | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| |

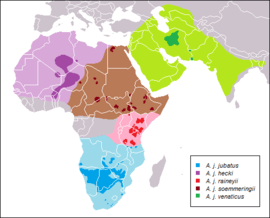

| The range of the cheetah | |

| Synonyms | |

The cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) is a big cat in the subfamily Felinae that inhabits most of Africa and parts of Iran. It is the only extant member of the genus Acinonyx. The cheetah can run as fast as 109.4 to 120.7 km/h (68.0 to 75.0 mph), faster than any other land animal. It covers distances up to 500 m (1,640 ft) in short bursts, and can accelerate from 0 to 96 km/h (0 to 60 mph) in three seconds.[3] The cheetah's closest extant relatives are the puma and jaguarundi of the Americas. Cheetahs are notable for adaptations in the paws as they are one of the few felids with only semi-retractable claws.[4]

Their main hunting strategy is to trip swift prey such as various antelope species and hares with its dewclaw. Almost every facet of the cheetah's anatomy has evolved to maximise its success in the chase, the result of an evolutionary arms race with its prey. Due to this specialisation, however, the cheetah is poorly equipped to defend itself against other large predators, with speed being its main means of defence. In the wild, the cheetah is a prolific breeder, with up to nine cubs in a litter. The majority of cubs do not survive to adulthood, mainly as a result of depredation from other predators. The rate of cub mortality varies from area to area, from 50% to 75%,[5] and in extreme cases such as the Serengeti ecosystem, up to 90%. Cheetahs are notoriously poor breeders in captivity, though several organizations, such as the De Wildt Cheetah and Wildlife Centre, have succeeded in breeding high numbers of cubs.

The cheetah is listed as vulnerable, facing various threats including loss of habitat and prey; conflict with humans; the illegal pet trade; competition with and predation by other carnivores; and a gene pool with very low variability. It is a charismatic species and many captive cats are "ambassadors" for their species and wildlife conservation in general.

Etymology

The vernacular name "cheetah" is derived from the Hindi word "चीता" (cītā), which in turn comes from the Sanskrit word citrakāyaḥ, meaning "bright" or "variegated".[6] The first recorded use of this word was in 1610.[7] An alternative name for the cheetah is "hunting leopard".[8] The scientific name of the cheetah is Acinonyx jubatus.[9] The generic name Acinonyx could have originated from the combination of three Greek words: a means "not", kaina means thorn, and onus means claw. A rough translation of the word would be "non-moving claws", a reference to the limited retractability (capability of being drawn inside) of the claws of the cheetah. The specific name jubatus means "maned" in Latin, referring to the dorsal crest of this animal.[10]

Taxonomy and phylogeny

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Puma lineage, depicted along with the Lynx and Felis lineages of the family Felidae (Werdelin et.al. 2009) |

The cheetah is the only extant species of the genus Acinonyx. It is classified under the subfamily Felinae and family Felidae, the family that also includes large cats such as lion, tiger and leopard. The species was first described by German naturalist Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber in his 1775 publication Die Säugethiere in Abbildungen nach der Natur mit Beschreibungen.[9]

The cheetah has a particularly close relationship with the cougar (Puma concolor) and the jaguarundi (P. yagouaroundi) in comparison to other felids. These three species together form the Puma lineage, one of the eight lineages of Felidae.[11][12] In fact, the jaguarundi is more closely related to the cougar and the cheetah than to any other felid.[13] The cheetah is also close to Felis, which comprises smaller cats.[14]

Although the cheetah is an African cat, molecular evidence indicates that all the three species of the Puma lineage evolved in North America 2 to 3 million years ago, where they possibly had a common ancestor during the Miocene.[15] They possibly diverged from this ancestor 8.25 million years ago.[11] The cheetah diverged from the puma and the jaguarundi around 6.7 million years ago.[16] A genome study concluded that cheetahs originated in North America and spread to Asia and Africa around 100,000 years ago during the late Pleistocene. The result of this first migration also caused the first genetic bottleneck in their population when cheetahs became extinct in North America at the end of the last Ice age. This was followed by a second bottleneck between 10,000-20,000 years ago, further lowering their genetic diversity.[17]

Cheetah fossils found in the lower beds of the Olduvai Gorge site in northern Tanzania date back to the Pleistocene.[18] The extinct species of Acinonyx are older than the cheetah, with the oldest known from the late Pliocene; these fossils are about 3 million years old.[2] These species include Acinonyx pardinensis (Pliocene epoch), much larger than the modern cheetah, and A. intermedius (mid-Pleistocene period).[19] While the range of A. intermedius stretched from Europe to China, A. pardinensis spanned over Eurasia as well as eastern and southern Asia. Additionally, these two species were contemporaries of the cheetah nearly 10,000 years ago, when it occurred throughout Asia, Africa and North America.[2] A variety of cheetah larger in size existed in Europe at some point of time, but fell to extinction around 0.5 million years ago.[8]

Extinct North American cats resembling the cheetah had historically been assigned to Felis, Pumas or Acinonyx. However, a phylogenetic analysis in 1990 placed these species under the genus Miracinonyx.[20] Miracinonyx exhibited a high degree of similarity with the cheetah. However in 1998, a DNA analysis showed that Miracinonyx inexpectatus, M. studeri, and M. trumani (early to late Pleistocene epoch),[19] found in North America, are not true cheetahs; in fact, they are close relatives of the cougar.[21] The cheetah was formerly considered to be particularly primitive among the cats and to have evolved approximately 18 million years ago. However, a 2000 study suggests the last common ancestor of all 40 existing species of felines lived more recently than about 11 million years ago. The same study indicates that the cheetah, while highly derived morphologically, is not of particularly ancient lineage, having separated from the cougar and the jaguarundi around six to seven million years ago.[21]

Subspecies

The five recognized subspecies of the cheetah are:[22]

- Asiatic cheetah (A. j. venaticus) (Griffith, 1821) : Also called the Iranian or Indian cheetah Formerly occurred across southwestern Asia and India.[23] According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), it is confined to Iran, and is thus the only surviving cheetah subspecies indigenous to Asia. It is Critically Endangered.[24] A 2004 study estimated the total population at 50-60.[25] Later, a 2007 study gave the total population in Iran as 60 to 100; the majority of individuals were likely to be juveniles. The population has declined sharply since the mid-1970s.[26]

- Northwest African cheetah (A. j. hecki) Hilzheimer, 1913: Also called the Saharan cheetah. Found in northwestern Africa; the IUCN confirms its presence in only four countries : Algeria, Benin, Burkina Faso and Niger. Small populations are known to exist in the Ahaggar and Tassili N'Ajjer National Parks (Algeria);[27] a 2003 study estimated a population of 20 to 40 individual in Ahaggar National Park.[28] In Niger, cheetah sightings have been reported from the Aïr Mountains, Ténéré, Termit Massif, Talak and Azaouak valley. A 1993 study reported a population of 50 from Ténéré. In Benin, the cheetah still survives in Pendjari National Park and W National Park. The status is obscure in Burkina Faso, where individuals may be confined to the southeastern region. With an estimated total world population of less than 250 mature individuals, it is listed as Critically Endangered.[29]

- South African cheetah (A. j. jubatus) (Schreber, 1775) : Also called the Namibian cheetah. Lives in Southern Africa where the geographical range has decreased to 21% of the historic range and now includes Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, South Africa and Zambia. In 2007, the population was roughly estimated at less than 5,000 to maximum 6,500 adult individuals.[30][31] In Namibia, the population has increased from about 2,500 in 1990 to 3,500 today.[32] It lives in grasslands, savannahs, arid environments, open fields and mountains, and occupies a medium size range among surviving subspecies. Occurs in several countries of southern Africa : Angola, Botswana, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe; extinct in Malawi and Democratic Republic of the Congo.[1]

- Sudan cheetah (A. j. soemmeringii) (Fitzinger, 1855) : Also called the Central or Northeast African cheetah. Found in the central and northeastern regions of the continent and in the Horn of Africa. This subspecies was considered identical to the South African cheetah until a 2011 genetic analysis demonstrated significant differences.[33][34] It is the second-largest of the surviving subspecies. In 2002, the total population was estimated at around 2,000 individuals in the wild.[35] Found in northeastern Africa - Ethiopia, Somalia, South Sudan and Sudan; possibly extinct in Djibouti and Eritrea, extinct in Egypt[1] - and central Africa: Chad, Central African Republic, Niger;[36] extinct in Cameroon, Democratic Republic of the Congo and Nigeria[1]

- Tanzanian cheetah (A. j. raineyii syn. A. j. fearsoni) Heller, 1913 : Also called the East African cheetah. Found in Kenya, Somalia, Tanzania, and Uganda. The total population in 2007 was estimated at 2,572 adults and independent adolescents.[1] As of 2015, it is estimated that 800 to 1,200 cheetahs live in Kenya, therefore makes the country the main stronghold for the East African cheetahs.[37] This subspecies lives in savannahs, grasslands, plains and forests. Their largest populations are found at Maasai Mara and at the Serengeti ecosystem where the rate of cheetah cubs' mortality varies up to 90%. Tanzanian cheetahs are the second most common subspecies after the most numerous South African cheetah. It is the tallest and largest subspecies. Occurs in several countries of eastern Africa : Kenya, Somalia, Tanzania, and Uganda;[1] extinct in Burundi, Democratic Republic of the Congo and Rwanda.

| The five subspecies of the cheetah | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Genetics

The diploid number of chromosomes in the cheetah is 38, the same as any other felid, save for the ocelot and the margay, whose diploid number of chromosomes is 36.[14] The cheetah has unusually low genetic variability. This is might be accompanied by a very low sperm count, motility, deformed flagella, difficulty in captive breeding and susceptibility to disease.[38][39] Skin grafts between unrelated cheetahs illustrates this point, seconded by electrophoretic evidence and reproductive surveys.[40] It is believed that the species went through a prolonged period of inbreeding following a genetic bottleneck during the last Ice age.[41] This suggests that genetic monomorphism (lack of genetic variability) did not prevent the cheetah from flourishing across two continents for thousands of years.[42]

King cheetah

The king cheetah is a variety of cheetah with a rare mutation for cream-colored fur marked with large, blotchy spots and three dark, wide stripes extending from their neck to the tail.[43] In 1926, Major A. Cooper wrote about an animal he had shot near Salisbury (modern-day Harare) in southern Rhodesia (modern-day Zimbabwe). Describing the animal, he noted its remarkable similarity to the cheetah, but the body of this individual was covered with fur as thick as that of a snow leopard and the spots merged to form stripes. He suggested that it could be a cross between a leopard and a cheetah. After further similar animals were discovered, it was established they were similar to the cheetah in having non-retractable claws - a characteristic feature of the cheetah.[44][45]

English zoologist R. I. Pocock described it as a new species named Acinonyx rex, which translated to "king cheetah".[45] However, he reversed this decision in 1939 due to lack of evidence; but in 1928, a skin purchased by the English zoologist Walter Rothschild was found to be intermediate in pattern between the king cheetah and spotted cheetah and English hunter-naturalist Abel Chapman considered it to be a color form of the spotted cheetah.[46][10] 22 such skins were found between 1926 and 1974. Since 1927, the king cheetah was reported five more times in the wild. Although strangely marked skins had come from Africa, a live king cheetah was not photographed until 1974 in South Africa's Kruger National Park. Cryptozoologists Paul and Lena Bottriell photographed one during an expedition in 1975. They also obtained stuffed specimens. It appeared larger than a spotted cheetah and its fur had a different texture. There was another wild sighting in 1986 — the first in seven years. By 1987, 38 specimens had been recorded, many from pelts.[47]

In May 1981, two spotted sisters gave birth at the De Wildt Cheetah and Wildlife Centre (South Africa) and each litter contained one king cheetah. The sisters had both mated with a wild male from the Transvaal region (where king cheetahs had been recorded). Further king cheetahs were later born at the Centre. It has been known to exist in Zimbabwe, Botswana and in the northern part of South Africa's Transvaal province. In 2012, the cause of this alternative coat pattern was found to be a mutation in the gene for transmembrane aminopeptidase Q (Taqpep), the same gene responsible for the striped "mackerel" versus blotchy "classic" patterning seen in tabby cats.[48] Hence genetically the king cheetah is simply a variety of the common cheetah and not a separate species. This case is similar to that of the black panthers.[43] The mutation is recessive, which is a reason behind the rareness of the mutation. As a result, if two mating cheetah have the same gene, then a quarter of their offspring can be expected to be king cheetah.[12]

Characteristics

The cheetah is a big cat with several distinctive features - a slender body, deep chest, spotted pelage, a small rounded head, black tear-like streaks on the face, long thin legs and a long spotted tail.[49] Its lightly built, thin form is in sharp contrast with the robust build of the other big cats.[12] The head-and-body length ranges from 112–150 centimetres (44–59 in).[49] The cheetah reaches nearly 70 to 90 centimetres (28 to 35 in) at the shoulder.[50][49] Thus it is clearly taller than the leopard, that stands nearly 55–70 centimetres (22–28 in) at the shoulder. The weight ranges of the cheetah overlaps extensively with that of the leopard, that weighs from 28–65 kilograms (62–143 lb).[51] On the other hand, the cheetah is significantly shorter than the lion, whose average height is nearly 120 centimetres (47 in). Moreover, it is much lighter than the lion, among which females weigh 126 kilograms (278 lb) and the males are much heavier, 186 kilograms (410 lb).[52] Based on measurements, the smallest cheetah have been reported from the Sahara, northeastern Africa and Iran.[16] A sexually dimorphic species, male cheetah are generally larger than the females.[50]

The head is small and streamlined, thus adding to the agility of the cheetah.[53] The Saharan cheetah are observed to have narrow canine faces.[16] Small, short and rounded, the ears have black patches on their back; the fringes and base of the ears, however, are tawny. The high-set eyes have round pupils.[50][54] The whiskers, shorter and fewer than those of other felids, are fine and inconspicuous.[55] The pronounced tear streaks are unique to the cheetah. These streaks originate from the corner of the eyes, following which they run down the nose till the mouth. Their role is obscure - they may be serving as a shield for the eyes against the sun's glare, a helpful feature as the cheetah is a diurnal hunter; another purpose could be to define facial expressions.[16]

Basically yellowish tan or rufous to grayish white, the coat of the cheetah is uniformly covered with nearly 2,000 black, solid spots. The upper parts are in stark contrast to the underbelly, that is completely white.[49] Each spot measures nearly 3.2–5.1 centimetres (1.3–2.0 in) across.[56] Every cheetah has a unique pattern of spots on its coat; hence this serves as a distinct identity for each individual.[16][2][56] Cheetah fur is short and often coarse. Fluffy fur covers the chest and the ventral side.[49] Several color morphs of the cheetah have been identified, including melanistic and white forms.[57] Black cheetah have been observed in Kenya and Zambia. In 1877-1878, English zoologist Philip Sclater described two partially albino specimens from South Africa.[12] A ticked (tabby) cheetah was photographed in Kenya in 2012.[58] Juveniles are typically black with long, loose blue to gray hair.[49] A short mane, about 8 centimetres (3.1 in) long, on the neck and the shoulders, is all that remains of the cape in adult cheetah.[12] The exceptionally long and muscular tail measures 60–80 centimetres (24–31 in), and ends in a bushy white tuft.[59] While the first two-thirds of the tail are covered in spots, the final part is marked with four to six dark rings or stripes.[56][12] The arrangement of the terminal stripes of the tail differs among individuals, but the stripe patterns of siblings are very similar. In fact, the tail of an individual will typically resemble its sibling's to a greater extent than it resembles its mother's or any other individual's.[12]

The cheetah is often confused with the leopard and the cougar. However, the leopard is marked with rosettes while the cheetah with spots; added to this the former lacks the tear streaks of the cheetah.[60] Moreover, the leopard has rose-like spots instead of the small round ones of the cheetah.[61] The cougar possesses neither the tear streaks nor the spotted coat pattern of the cheetah.[2] The serval has a very similar form as the cheetah, but is significantly smaller. Moreover, it has a shorter tail and spots that fuse to form stripes on the back.[62]

Anatomy

The cheetah differs notably from the other big cats in terms of morphology.[63] The face and the jaw are unusually shortened and the sagittal crest is poorly developed, possibly to reduce weight and enhance speed. In fact, the skull resembles that of the smaller cats. Another point of similarity to the small cats is the long and flexible spine, in contrast with the stiff and short one of other large felids.[64] A 2001 study of felid morphology stated that the relatively earlier truncation of the development of the middle phalanx bone in cheetah in comparison to other felids could be a major reason for the peculiar morphology of the cheetah.[63] In the Puma lineage, the cheetah has similar skull morphology as the puma - both have short, wide skulls - while that of jaguarundi is different.[65]

The cheetah has a total of 30 teeth; the dental formula is 3.1.3.13.1.2.1. The sharp, narrow cheek teeth help in tearing flesh, whereas the small and flat canine teeth bite the throat of the prey to suffocate it. Males have slightly bigger heads with wider incisors and longer mandibles than females.[2] The muscles between the skull and jaw are short, and thus do not allow the cheetah to open its mouth as much as other cats.[12] Digitigrade animals, the cheetah have tough foot pads that make it convenient to run on firm ground. The hindlegs are longer than the forelegs. The relatively longer metacarpals, metatarsals (of lower leg), radius, ulna, tibia and fibula increase the length of each jump. The straightening of the flexible vertebral column also adds to the length.[2]

Cheetah have a high concentration of nerve cells, arranged in a band in the center of the eyes. This arrangement is called a "visual streak", that significantly enhances the sharpness of the vision. The visual streak is most concentrated and efficient in the cheetah among most of the felids.[64] The nasal passages are short and large; the smallness of the canines helps to accommodate the large nostrils.[2] The cheetah is unable to roar due to the presence of a sharp-edged vocal fold with a sharp edge in the larynx.[2][66]

The paws of the cheetah are narrower than those of other felids.[2] The slightly curved claws lack a protective sheath, and are weakly retractable (semi-retractable).[49][50] This is a major point of difference between the cheetah and the other big cats, that have fully retractable claws.[67] The limited retraction of claws adds a canine quality to this felid. The aforementioned 2001 study showed that the claws of cheetah have features intermediate between those of felids and the wolf. This peculiar similarity between the cheetah and the wolf was attributed to convergent evolution.[63] Additionally, the claws of cheetah are shorter as well as straighter than those of other cats.[12] Absence of protection makes the claws blunt.[16] However, the large and strongly curved dewclaw has notable sharpness.[68]

Distribution and habitat

Cheetahs inhabit dry and open areas, such as clayey deserts, steppes, savannahs and grasslands, acacia scrubs and light woodland. Most cheetahs never enter dense forests or thickets except Asiatic cheetahs that lived in dense forested regions in India. In Africa, cheetahs once occurred in these types of habitat from the Mediterranean to the Cape Peninsula, and in Asia from the northern Arabian Peninsula eastwards to the Deccan Plateau and West Bengal in India. Until the first half of the 20th century, cheetahs were killed by sport hunters and became scarce throughout their range. In South Africa they were hunted to almost extermination by the 1930s. In Arabia, there have not been any reliable records since the 1950s. The Qattara Depression in Egypt was considered their last refuge by the 1960s. In India, they were declared extinct in 1952.[69]

Since the 1950s, cheetahs were eradicated in at least 13 countries by farmers and trophy hunters. Between 1978 and 1994, more than 9,500 cheetahs were killed on Namibian farmlands alone. Today, cheetah populations are small and isolated, with viable populations in about half of the countries where cheetahs survive. Their remaining strongholds are in Kenya, Tanzania, Botswana and Namibia.[70] The remaining population of Asiatic cheetahs survives in fragmented protected areas around the Dasht-e-Kavir in eastern Iran.[71] In 2008, this population was considered very small, comprising less than 50 reproducing individuals.[72]

Ecology and behavior

Unlike males, females are solitary and tend to avoid each other, though some mother/daughter pairs have been known to be formed for small periods of time. The cheetah has a unique, well-structured social order. Females live alone, except when they are raising cubs and they raise their cubs on their own. The first eighteen months of a cub's life are important; cubs must learn many lessons, because survival depends on knowing how to hunt wild prey species and avoid other predators. At 18 months, the mother leaves the cubs, who then form a sibling ("sib") group that will stay together for another six months. At about two years, the female siblings leave the group, and the young males remain together for life.

Territories

Males

Males are often social and may group together for life, usually with their brothers in the same litter; although if a cub is the only male in the litter then two or three lone males may form a group, or a lone male may join an existing group. These groups are called coalitions. In the Serengeti, it was found that 41% of the adult males were solitary, 40% lived in pairs and 19% lived in trios.[73]

A coalition is six times more likely to obtain an animal territory than a lone male, although studies have shown that coalitions keep their territories just as long as lone males— between four to four and a half years.

Males are territorial. Females' home ranges can be very large and a territory including several females' ranges is impossible to defend. Instead, males choose the points at which several of the females' home ranges overlap, creating a much smaller space, which can be properly defended against intruders while maximizing the chance of reproduction. Coalitions will try their best to maintain territories to find females with whom they will mate. The size of the territory also depends on the available resources; depending on the habitat, the size of a male's territory can vary greatly from 37 to 160 km2 (14 to 62 sq mi).

Scent is an important means of communication among cheetahs. Males mark their territory by urinating or defecating on objects that stand out, such as trees, logs, or termite mounds. When male cheetahs urine-mark their territories, they stand less than one meter away from a tree or rock surface with the tail raised, pointing the penis either horizontally backward or 60° upward.[74] Male coalitions are able to defend the best territories through joint scent-marking.[75] Males will attempt to kill any intruders, and fights result in serious injury or death.[76][77]

Females

Unlike males and other felines, females do not establish territories. Instead, the area they live in is termed a home range. These overlap with other females' home ranges, often those of their daughters, mothers, or sisters. Females always hunt alone, although cubs will accompany their mothers to learn to hunt once they reach the age of five to six weeks.

The size of a home range depends entirely on the availability of prey. Cheetahs in southern African woodlands have ranges as small as 34 km2 (13 sq mi), while in some parts of Namibia they can reach 1,500 km2 (580 sq mi).

Vocalizations

The cheetah cannot roar, but ranks among the more vocal felids. Several sources refer to a wide variety of cheetah vocalizations, but most of these lack a detailed acoustic description, which makes it difficult to reliably assess exactly what terms refer to exactly what vocalizations. A short review of the terminology encountered is found in.[78] Some of the vocalizations listed in the literature are:

- Chirping: When a cheetah attempts to find another, or a mother tries to locate her cubs, it uses a high-pitched barking called chirping. The chirps made by a cheetah cub sound more like a bird chirping, and so are termed chirping, too.

- Churring or stuttering: This vocalization is emitted by a cheetah during social meetings. A churr can be seen as a social invitation to other cheetahs, an expression of interest, uncertainty, or appeasement or during meetings with the opposite sex (although each sex churrs for different reasons).

- Growling: This vocalization is often accompanied by hissing and spitting and is exhibited by the cheetah during annoyance, or when faced with danger.

- Yowling: This is an escalated version of growling, usually displayed when danger worsens.

- Agonistic vocalizations: a combination of growls, moans, hisses and the "trademark" cheetah spit, which is most often accompanied by a forceful "paw hit" on the ground.[78]

- Purring: This is made when the cheetah is content, usually during pleasant social meetings (mostly between cubs and their mothers). A characteristic of purring is that it is realized on both egressive and ingressive airstream, as seen and heard on online video and audio.[79][80][81][82][83][84]

Diet and hunting

Cheetahs are carnivores preferring medium-sized prey with a body mass ranging from 23 to 56 kg (51 to 123 lb), comprising Thomson's gazelle, impala, blesbok, springbok, Grant's gazelle, reedbuck and duiker. They can feed on these species rapidly before kleptoparasites arrive, and the risk of getting injured while hunting them is minimal. When available they also prey on steenbok, kudu, waterbuck, bushbuck, hartebeest, nyala, sable antelope, bat-eared fox, roan antelope and oribi. Less frequently they prey on ostrich, warthog, wildebeest, gemsbok and zebra.[85] Asiatic cheetahs prey on chinkara, desert hares, Goitered gazelle, ibex and wild sheep.[86] The blackbuck used to be one of the most favorable preys for the Asiatic cheetahs.

The diet of a cheetah depends on the area in which it lives. For example, on the East African plains, its preferred prey is the Thomson's gazelle (somewhat smaller than the cheetah). In contrast, in Kwa-Zulu Natal, the preferred prey is the significantly larger nyala, males of which can weigh up to 130 kg (290 lb).[87] Cheetahs concentrate on individuals that have strayed some distance from their group, and do not necessarily seek out old or weak ones. They do, however, opt for young and adolescent targets, which make up about 50% of the cheetah diet despite constituting only a small portion of the prey population.[88]

Cheetahs hunt by vision rather than by scent. They stalk their prey to within 10–30 m (33–98 ft), then chase it. The chase usually lasts less than a minute; if the cheetah fails to make a kill quickly, it will give up. Cheetahs have an average hunting success rate of 40–50%.[89][90] They are diurnal hunters that hunt early in the morning or late in the afternoon when temperature has cooled down. They also hunt on moonlit nights when visibility allows.[91]

Cheetahs kill their prey by tripping it during the chase, then biting it on the underside of the throat to suffocate it; the cheetah is not strong enough to break the necks of most prey. Rapid deceleration, to enable the cheetah to bite its quarry before the latter can get up and running again, is therefore a crucial component of a successful hunt.[92] The bite may also puncture a vital artery in the neck. Then the cheetah proceeds to devour its catch as quickly as possible before the kill is taken by stronger predators.

Speed and acceleration

.ogv.jpg)

The cheetah is the fastest land mammal.[93][94][95][96][97][98] Its body is specialized for speed.[99][100] Biologist R. D. Estes describes the cheetah as the "felid version of the Greyhound", as both have somewhat similar forms and the ability of to reach tremendous speeds in a shorter time interval compared to other mammals.[49][101] Its thin and light body make it well-suited to short, explosive bursts of high speed. Not just raw speed, but also rapid acceleration and an ability to execute drastic changes in direction while moving at speed accounts for much of the cheetah's ability to catch prey.[102][103]

One stride or jump of a cheetah averages 7 metres (23 ft). The speed ranges from 90–108 kilometres per hour (56–67 mph); the most reliable measurement of the typical speed in a sprint is 112 kilometres per hour (70 mph).[104][105][106] As this is an averaged value, a cheetah's maximum speed is presumably still higher.[107] Though the speeds attained by cheetah are marginally higher than the pronghorn,[108] that can sprint at 88.5 kilometres per hour (55.0 mph), and the springbok,[109] that can attain 88 kilometres per hour (55 mph), the cheetah has a greater probability of succeeding in the chase due to its exceptional acceleration - it can attain a speed of 75 kilometres per hour (47 mph) in just two seconds.[12]

Data from 367 runs by five wild adult cheetahs, three female and two male, wearing tracking collars yielded a top speed of 93 km/h (58 mph), with an average of 48 to 56 km/h (30 to 35 mph). Speed increased by almost 10 km/h (6 mph) in a single stride, while the average distance covered was 173 m (568 ft). Maximum run distances ranged from 407 to 559 m (1,335 to 1,834 ft). Given the moderate speeds of many chases, the ability to rapidly change direction was likely the crucial characteristic ensuring hunting success.[92][110][111]

The large nasal passages ensure fast flow of sufficient air, and the enlarged heart and lungs allow the enrichment of blood with oxygen in a short time. This allows the cheetah to rapidly regain its stamina after a chase.[2][12] During a typical chase, its respiratory rate increases from 60 to 150 breaths per minute.[89] While running, in addition to having good traction due to its semi-retractable claws, the cheetah uses its tail as a rudder-like means of steering to allow it to make sharp turns, necessary to outflank antelopes that often make such turns to escape.[53][12] The protracted claws increase grip over the ground, while foot pads make the sprint more convenient over tough ground. The tight binding of the tibia and the fibula restrict rotation about the lower leg, thus stabilizing the animal throughout the sprint; the demerit, however, is that this reduces climbing efficiency. The pendulum-like motion of the scapula increases the stride length and assists in shock absorption. The extension of the vertebral column can add as much as 76 centimetres (30 in) to the length of a stride.[105][112] During more than half of the time of the sprint, the animal has all the four limbs in the air; this contributes to the stride length.[113]

In the course of a sprint, the heat production in cheetah exceeds more than 50% of the normal. The cheetah retains as much as 90% of the heat generated in its body during the chase, which is considerably larger than the 20% in the case of the domestic dog.[12] The cheetah does not indulge in long distance chases, lest it should develop dangerous temperatures, nearly 40–41 °C (104–106 °F). The cheetah will run no more than 500 metres (1,600 ft) at the tremendous speeds of 80–112 kilometres per hour (50–70 mph). This is very rare as most chases are within 100 metres (330 ft).[114][115]

Enemies and competitors

Despite their speed and hunting prowess, cheetahs are largely outranked by other large predators in most of their range. Because they have evolved for short bursts of extreme speed at the expense of strength, they cannot defend themselves against most of Africa's other predator species. They usually avoid fighting and will surrender a kill immediately to even a single hyena, rather than risk injury. Because cheetahs rely primarily on their acceleration and manoeuvrability to obtain their meals, any injury that impedes their altering speed and direction could essentially be life-threatening.

Cheetahs lose around 10 to 15% of their kills to other predators,[88] though it was once thought to be as high as 50%.[89] Cheetahs avoid competition by hunting at different times of the day and by eating immediately after the kill. Due to the reduction in habitat in Africa, cheetahs in protected areas face greater pressure from other larger predators, causing them to live outside of reserves and increasingly coming into conflict with humans.[116] In Namibia, where the largest population of wild cheetah lives, 90% of these cheetahs live on farmland.

Reproduction

Females reach sexual maturity at the age of 21 to 22 months. Captive cheetahs are receptive for up to 14 days and have an estrous cycle of 3 to 27 days.[2] Male and female stay together for 2–3 days and mate mostly at night. Females give birth after a gestation of 90–95 days. In the wild, litter size is seldom more than six cubs, who stay in the lair for about the first eight weeks. Then they accompany their mother on hunts, but are still nursed up to the age of four months. When cubs leave their mothers and become independent, siblings stay together for some time.[74]

In the Serengeti, average age of independence of 70 observed litters was 17.1 months. Young females had their first litters at the age of about 2.4 years and subsequent litters about 20 months later. Nearly 50% of cubs survived to independence from their mothers. Females reached an average age of 6.2 years, and males of 5.3 years.[117] A genetic analysis of cheetahs in the Serengeti showed that females are polyandrous. Of 47 litters, 10 were sired by two to three males.[118]

Cubs weigh from 250 to 300 g (8.8 to 10.6 oz) at birth. Their nape, shoulders and back is thickly covered with long bluish grey hair, which is considered to act as camouflage from predators.[74] This downy underlying fur, called a mantle, gives them a mane or Mohawk-type appearance; this fur is shed as the cheetah grows older. It has been speculated that this mane gives a cheetah cub the appearance of the honey badger, to scare away potential aggressors.[119]

Cheetah cub mortality is caused by predation from lions, leopards, spotted hyenas and African wild dogs. Of 125 cubs observed between October 1987 and September 1990 in the Serengeti National Park, not more than seven cubs survived to the age of 14 months.[120] This high cub mortality has not been observed in areas where fewer large predators were present. In the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, 24 of 67 observed cubs survived to the age of 14 months.[121]

Cheetah cubs often hide in thick brush for safety. Female cheetahs defend their young and are at times successful in driving predators away from their cubs. Coalitions of male cheetahs can also chase away other predators, depending on the coalition size and the size and number of the predator. Healthy adult cheetahs have few enemies since they are able to escape fast.

Relationship with humans

Economic importance

Cheetah fur was formerly regarded as a status symbol. Today, cheetahs have a growing economic importance for ecotourism and they are also found in zoos. White Oak Conservation in Yulee, Florida, which maintains a significant population of cheetahs, has cited that captive management presents challenges because of health, nutrition and socialization of the cats, but that these have been overcome through collaborations among wildlife facilities.[122]

Cheetahs are far less aggressive than other felids, and in some parts of the world are considered a prestigious possession. Cheetah cubs are taken from the wild for the illegal wildlife trade and can be found for sale through street markets and the Internet. However, cheetahs do not breed well in captivity and legal breeding facilities are unable to meet the demand. Thus, the proliferation of wild cheetah taken for the illegal pet trade has the potential of decimating wild populations. The Cheetah Conservation Fund estimates that hundreds of cheetah cubs are taken from the wild every year to be sold as pets; only about one in six survive.[123]

Cheetahs living outside of protected areas often inhabit farmland, where they are shot by farmers who believe that they eat livestock. Recent evidence has shown, however, that cheetahs will not attack and eat livestock if they can avoid doing so, as they prefer their wild prey.[124] The Cheetah Conservation Fund has designed and implemented programs to prevent predators' conflict with humans. These programs aim at helping the farmers to protect their livelihoods through education, livelihood development, habitat restoration and predator-friendly farming techniques, such as the highly-successful use of livestock guarding dogs.[125]

Taming

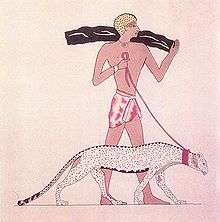

Ancient Egyptians often kept cheetahs as pets, and also tamed and trained them for hunting, although they did not domesticate them. Cheetahs would be taken to hunting fields in low-sided carts or by horseback, hooded and blindfolded, and kept on leashes while dogs flushed out their prey. When the prey was near enough, the cheetahs would be released and their blindfolds removed. This tradition was passed on to the ancient Persians and brought to India, where the practice was continued by Indian princes into the twentieth century. Cheetahs continued to be associated with royalty and elegance, their use as pets spreading just as their hunting skills were. Other such princes and kings kept them as pets, including Genghis Khan and Charlemagne, who boasted of having kept cheetahs within their palace grounds. Akbar the Great, ruler of the Mughal Empire from 1556 to 1605, kept as many as 1,000 cheetahs.[89] As recently as the 1930s, the Emperor of Ethiopia, Haile Selassie, was often photographed leading a cheetah by a leash.

Cheetahs are still tamed in the modern world, much to their detriment as the demand in the illegal pet trade continues. However, their tameability has also allowed many registered institutions to educate the public by training cheetahs as educational ambassadors. One example is Burmani, who has been raised in England at Eagle Heights wild animal park from the age of three months. He was bred in a deer park in Germany. He is so tame that he has lost his hunting instinct.[126]

Conservation status

Cheetah cubs have a high mortality rate due to predation by other carnivores, such as the lion and hyena, and perhaps genetic factors. It has been suggested that the low genetic diversity of cheetahs is a cause of poor sperm, birth defects, cramped teeth, kinked tails, and bent limbs. Some biologists even believe that they are too inbred to flourish as a species.[127] Note, however, that they lost most of their genetic diversity thousands of years ago (see the beginning of this article), and yet have only been in decline in the last century or so, from 100,000 in the early 1900s to 10,000 today, due to loss of habitat and prey, human-wildlife conflict and the illegal pet trade.[128]

Cheetahs are included on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) list of vulnerable species (African subspecies threatened, Asiatic subspecies in critical situation) as well as on the US Endangered Species Act: threatened species - Appendix I of CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species). In 2014, the CITES Standing Committee recognized cheetahs as a "species of priority' in north-east Africa in their strategies to counter wildlife trafficking.[129]

Approximately 10,000 cheetahs remain in the wild in twenty-three African countries; Namibia has the most, with about 3,500. Another 50 to 60 critically endangered Asiatic cheetahs are thought to remain in Iran. There have been some successful breeding programs in zoos around the world. Additionally, recent research into improving in vitro fertilisation and embryo culture techniques have the potential of consistently producing embryos for transfer.[130]

Founded in Namibia in 1990, the Cheetah Conservation Fund's mission is to be the world's resource charged with protecting the cheetah and to ensure its future. The organization works with all stakeholders within the cheetah's ecosystem to develop best practices in research, education and ecology and create a sustainable model from which all other species, including people, will benefit. The Cheetah Conservation Fund has close links and assists in training and sharing program successes with other countries where cheetahs live, including Botswana, Kenya, Tanzania, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Iran and Algeria. The organization's international program includes distributing materials, lending resources and support, and providing training through Africa and the rest of the world.

National Metapopulation Project in South Africa

The South African cheetah used to be widespread in several areas of South Africa, until after years of hunting and conflicts, the population have dramatically declined and went extinct in multiple regions of the country. The species live mostly on the eastern and northern locations of South Africa.

Since the 1960s and onwards, the cheetahs are being reintroduced in their former ranges. The first known reintroductions were in KwaZulu Natal, Gauteng, Lowveld, Eastern Cape, Western Cape and Southern Kalahari. South African cheetahs have also returned in the Karoo, starting with Samara Private Game Reserve. As of 2013, the cheetah population has increased from between 550 and 850 individuals to over 1,300 individuals in South Africa after many conservation efforts for the species.

A National Cheetah Metapopulation Project was launched in 2011 by the Endangered Wildlife Trust (EWT).[131] Its purpose is to develop and co-ordinate a national metapopulation management plan for cheetahs in smaller fenced reserves in South Africa. For instance, the cheetahs have been reintroduced in approx. 50 of these South African reserves. Fragmented subpopulations of South African cheetahs are currently increasing in a few hundreds.[132]

For the first time after 100 years of extinction since the colonial period, the cheetah has recently been reintroduced into the Free State in 2013,[133] with two male wild cheetahs that have been relocated from the Eastern Cape's Amakhala Game Reserve to the Free State's Laohu Valley Reserve, where the critically endangered South China tiger from Save China's Tigers (SCT) are part of a rewilding project in South Africa. A female cheetah has yet to be reintroduced to Laohu Valley.[134]

Re-introduction project in India

The Asiatic cheetahs have been known to exist in India for a very long time, but as a result of hunting and other causes, cheetahs have been extinct in India since the 1940s. A captive propagation project has been proposed. Minister of Environment and Forests Jairam Ramesh told the Rajya Sabha on 7 July 2009, "The cheetah is the only animal that has been described extinct in India in the last 100 years. We have to get them from abroad to repopulate the species." He was responding to a call for attention from Rajiv Pratap Rudy of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). "The plan to bring back the cheetah, which fell to indiscriminate hunting and complex factors like a fragile breeding pattern is audacious given the problems besetting tiger conservation." Two naturalists, Divya Bhanusinh and MK Ranjit Singh, suggested importing the South African cheetahs from Namibia, as they can't afford to relocate the critically endangered Asiatic cheetahs from Iran. The imported Namibian cheetahs will be bred in captivity and, in time, released in the wild in suitable habitats for the cheetahs.[135]

However, in 2012, the plan to reintroduce the African cheetahs to India has been suspended after discovering the distinctness between the cheetahs from Asia and Africa, having been separated between 32,000 to 67,000 years ago.[136][137]

In popular culture

- In Titian's Bacchus and Ariadne (1523), the god's chariot is borne by cheetahs (which were used as hunting animals in Renaissance Italy). Cheetahs were often associated with the god Dionysus, whom the Romans called Bacchus.

- George Stubbs' Cheetah with Two Indian Attendants and a Stag (1764–1765) also shows the cheetah as a hunting animal and commemorates the gift of a cheetah to George III by the English Governor of Madras, Sir George Pigot

- The Caress (1896), by the Belgian symbolist painter Fernand Khnopff (1858–1921), is a representation of the myth of Oedipus and the Sphinx and portrays a creature with a woman's head and a cheetah's body (often misidentified as a leopard's).

- André Mercier's Our Friend Yambo (1961) is a curious biography of a cheetah adopted by a French couple and brought to live in Paris. It is seen as a French answer to Born Free (1960), whose author, Joy Adamson, produced a cheetah biography of her own, The Spotted Sphinx (1969).

- Hussein, An Entertainment, a novel by Patrick O'Brian set in India of the British Raj period, illustrates the practice of royalty keeping and training cheetahs to hunt antelopes.

- The book How It Was with Dooms tells the true story of a family raising an orphaned cheetah cub named Duma (the Swahili word for cheetah) in Kenya. The films Cheetah (1989) and Duma (2005) were both loosely based on this book.

- Similarly, Roger Hunt successfully tames a cheetah in Willard Price's Safari Adventure, after rescuing it from an elephant pit trap. The cheetah soon befriends a German shepherd dog called Zulu.

- The animated series ThunderCats had a main character who was an anthropomorphic cheetah named Cheetara.

- In 1986, Frito-Lay introduced an anthropomorphic cheetah, Chester Cheetah, as the mascot for their Cheetos.

- Harold and Kumar Go to White Castle has a subplot involving an escaped cheetah, which later smokes cannabis with the pair and allows them to ride it.

- Comic book superheroine Wonder Woman's chief adversary is Dr. Barbara Ann Minerva, alias The Cheetah.

- On the CGI animated show Beast Wars: Transformers, Cheetor, one of the main characters on the Maximal faction, had the beast form of a cheetah. This was also carried over as the beast form of the Cheetor Hasbro transformer.

- The Japanese anime Damekko Dōbutsu features a clumsy but sweet-natured cheetah named Chiiko.

- The first release of Apple Inc.'s Mac OS X was code-named "Cheetah", which set the pattern for the subsequent releases being named after big cats.

- In Visionaries: Knights of the Magical Light the character Witterquick as the totem of a Cheetah and could turn into one.

- Titled "Hunting at 60 mph", the PlayStation 3 game Afrika features a Cheetah hunting a gazelle as the game's first "big game hunt".

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Durant, S., Marker, L., Purchase, N., Belbachir, F., Hunter, L., Packer, C., Breitenmoser-Würsten, C., Sogbohossou, E. and Bauer, H. (2008). "Acinonyx jubatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2015.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Krausman, P. R.; Morales, S. M. (2005). "Acinonyx jubatus" (PDF). Mammalian Species 771: 1–6. doi:10.1644/1545-1410(2005)771[0001:aj]2.0.co;2.

- ↑ "Cheetah fast facts". Zoological Society of London. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- ↑ "Cheetah Fact Sheet" (PDF). Cheetah.org. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ↑ http://www.tigerhomes.org/animal/cheetah-facts.cfm

- ↑ cheetah (n.d.). The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Retrieved 2007-04-16.

- ↑ "Cheetah". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- 1 2 Mair, V.H. (2006). Contact and Exchange in the Ancient World. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. pp. 116–23. ISBN 978-0-8248-2884-4.

- 1 2 Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 532. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- 1 2 "Acinonyx jubatus". IUCN Cat Specialist Group. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- 1 2 Johnson, WE; O'Brien, SJ (1997). "Phylogenetic reconstruction of the Felidae using 16S rRNA and NADH-5 mitochondrial genes". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 44 Suppl 1: S98–116. doi:10.1007/PL00000060. PMID 9071018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Sunquist, F.; Sunquist, M. (2002). Wild Cats of the World. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 14–36. ISBN 0226779998.

- ↑ Sunquist, F.; Sunquist, M. (2014). The Wild Cat Book: Everything You Ever Wanted to Know about Cats. London: The University of Chicago Press. p. 175. ISBN 9780226145761.

- 1 2 Heptner, V.G. Heptner (1992). Mammals of the Soviet Union. Leiden: Brill. p. 61. ISBN 9004088768.

- ↑ Adams, D. B. (1979). "The Cheetah: Native American". Science 205 (4411): 1155–8. doi:10.1126/science.205.4411.1155.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hunter, L. (2015). Wild Cats of the World. China: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. pp. 167–76. ISBN 9781472912190.

- ↑ Dobrynin, P; Liu, S; Tamazian, G; Xiong, Z; Yurchenko, AA; Krasheninnikova, K; Kliver, S; Schmidt-Küntzel, A (2015). "Genomic legacy of the African cheetah, Acinonyx jubatus". Genome Biology 16: 277. doi:10.1186/s13059-015-0837-4.

- ↑ Leakey, L.S.B. (editor); Hopwood, A.T. (1951). Olduvai Gorge: A Report on the Evolution of the Hand-axe Culture in Beds I-IV. With Chapters on the Geology and Fauna. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 20–25.

- 1 2 Janis, C.M.; Scott, K.M.; Jacobs, L.L. (1998). Evolution of Tertiary Mammals of North America (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 236–40. ISBN 0521355192.

- ↑ Van Valkenburgh, B.; Grady, F.; Kurtén, B. (1990). "The Plio-Pleistocene cheetah-like Miracinonyx inexpectatus of North America". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 10 (4): 434–54. doi:10.1080/02724634.1990.10011827.

- 1 2 Mattern, M. Y.; D. A. McLennan (2000). "Phylogeny and Speciation of Felids". Cladistics 16 (2): 232–253. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2000.tb00354.x.

- ↑ "Acinonyx jubatus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ↑ Hildyard, A. (2001). Endangered Wildlife and Plants of the World. New York: Marshall Cavendish. pp. 250–1. ISBN 9780761471967.

- ↑ Durant, S., Marker, L., Purchase, N., Belbachir, F., Hunter, L., Packer, C., Breitenmoser-Würsten, C., Sogbohossou, E. and Bauer, H. (2008). "Acinonyx jubatus ssp. venaticus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2015.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature.

- ↑ Farhadinia, M.S. (2004). "The last stronghold: Cheetah in Iran" (PDF). Cat News: 11–14.

- ↑ Hunter, L.; Jowkar, H.; Ziaie, H.; Schaller, G.; Balme, G.; Walzer, C.; Ostrowski, S.; Zahler, P.; Robert-Charrue, N.; Kashiri, K.; Christie, S. (2007). "Conserving the Asiatic cheetah in Iran: launching the first radio-telemetry study". Cat News 46: 8–11.

- ↑ Busby, G.B.J.; Gottelli, D.; Durant, S.; Wacher, T.; Marker, L.; Belbachir, F.; De Smet, K.; Belbachir-Bazi, A.; Fellous, A.; Belgho, M. (2006). "A report from the Sahelo-Saharan interest group - parc national de L’Ahaggar survey, Algeria (March 2005), Part 5: Using Molecular Genetics to study the Presence of Endangered Carnivores (Nov.2006) [Unpublished report]" (PDF): 1–19.

- ↑ Hamdine, W.; Meftah, T.; Sehki, A. (2003). "Distribution and status of cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus) in the Algerian Central Sahara (Ahaggar and Tassili)". Mammalia 67 (3): 439–43.

- ↑ Durant, S., Marker, L., Purchase, N., Belbachir, F., Hunter, L., Packer, C., Breitenmoser-Würsten, C., Sogbohossou, E. and Bauer, H. (2008). "Acinonyx jubatus ssp. hecki". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2015.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature.

- ↑ IUCN/SSC. (2007). Regional conservation strategy for the cheetah and African wild dog in Southern Africa. IUCN Gland, Switzerland.

- ↑ Purchase, G., Marker, L., Marnewick, K., Klein, R., and Williams, S. (2007). "Regional assessment of the status, distribution and conservation needs of cheetahs in southern Africa". Cat News Special Issue 3: 44–46.

- ↑ "Namibia: Cheetah Conservation Fund Celebrates 25 Years". allAfrica.com. 20 March 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ↑ Ella Davies (24 January 2011). "Iran's endangered cheetahs are a unique subspecies". BBC News. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ↑ Three distinct cheetah populations, but Iran's on the brink, 18 January 2011, retrieved 6 April 2015

- ↑ "Cheetah, Acinonyx jubatus". Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ↑ Belbachir, F. 2008. (2008). "Acinonyx jubatus ssp. hecki". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2015.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature.

- ↑ Rupi Mangat (2 October 2015). "World cheetah population endangered". TheEastAfrican.co.ke. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- ↑ O'Brien, S.; Roelke, M.; Marker, L; Newman, A; Winkler, C.; Meltzer, D; Colly, L; Evermann, J.; Bush, M; Wildt, D. (1985). "Genetic basis for species vulnerability in the cheetah". Science 227 (4693): 1428–34. doi:10.1126/science.2983425.

- ↑ O'Brien, S.J.; Wildt, D.E.; Bush, M.; Caro, T.M.; FitzGibbon, C.; Aggundey, I.; Leakey, R.E. (1987). "East African cheetahs: evidence for two population bottlenecks?". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 84 (2): 508–11. PMID 3467370.

- ↑ Menotti-Raymond, M.; O'Brien, S.J. (1993). "Dating the genetic bottleneck of the African cheetah". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 90 (8): 3172–6. PMID 8475057.

- ↑ Yuhki, N.; O'Brien, S.J. (1990). "DNA variation of the mammalian major histocompatibility complex reflects genomic diversity and population history". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 87 (2): 836–40. PMID 1967831.

- ↑ Young, T.P. and A.H. Harcourt (1997). "Viva Caughley!". Conservation Biology 11: 831–832. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1997.011004831.x.

- 1 2 Thompson, S.E. (1998). Built For Speed : The Extraordinary, Enigmatic Cheetah. Minneapolis: Lerner Publications Co. pp. 66–8. ISBN 0822528541.

- ↑ Heuvelmans, B. (1995). On the Track of Unknown Animals (Revised, 3rd, English ed.). London: Kegan Paul International. pp. 500–2. ISBN 9780710304988.

- 1 2 Pocock, R. I. (21 August 2009). "Description of a new species of cheetah (Acinonyx)". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 97 (1): 245–52. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1927.tb02258.x.

- ↑ Shuker, K.P.N. (1989). Mystery Cats of the World : from Blue Tigers to Exmoor Beasts. London: Hale. p. 119. ISBN 0709037066.

- ↑ Bottriell, L. G. (1987). King Cheetah : The Story of the Quest. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9004085882.

- ↑ Kaelin et al. 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Estes, R.D. (2012). The Behavior Guide to African Mammals : Including Hoofed Mammals, Carnivores, Primates (20th anniversary ed.). Berkeley, California: University of California Press. pp. 377–83. ISBN 9780520272972.

- 1 2 3 4 Nowak, R.M. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World (6th ed.). Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 834–6. ISBN 0801857899.

- ↑ Estes, R.D. (2012). The Behavior Guide to African Mammals : Including Hoofed Mammals, Carnivores, Primates (20th anniversary ed.). Berkeley, California: University of California Press. pp. 367–9. ISBN 9780520272972.

- ↑ Estes, R.D. (2012). The Behavior Guide to African Mammals : Including Hoofed Mammals, Carnivores, Primates (20th anniversary ed.). Berkeley, California: University of California Press. pp. 369–77. ISBN 9780520272972.

- 1 2 Mills, G.; Hes, L. (1997). The Complete Book of Southern African mammals (1st ed.). Cape Town: Struik Publishers. pp. 175–7. ISBN 9780947430559.

- ↑ Kitchener, A.C.; Van Valkenburgh, B.; Yamaguchi, N. (2010). "Felid form and function" (PDF). Biology and Conservation of Wild Felids (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press): 83–106.

- ↑ Montgomery, S. (2014). Chasing Cheetahs : The Race to Save Africa's Fastest Cats. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 15–7. ISBN 9780547815497.

- 1 2 3 Arnold, C. (1989). Cheetah (1st Mulberry ed.). New York: William Morrow and Company. p. 16. ISBN 9780688116965.

- ↑ Eberhart, G.M. (2002). Mysterious Creatures : A Guide to Cryptozoology. Oxford: ABC-Clio. p. 90. ISBN 1576072835.

- ↑ Mail Foreign Service (25 April 2012). "The lesser-spotted cheetah: Rare big cat without traditional markings sighted in wild for first time in nearly 100 years". Daily Mail Online. Daily Mail. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ↑ Lehnert, E.R. "Acinonyx jubatus Cheetah". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ↑ Mivart, St. G.J. (1900). The Cat: An Introduction to the Study of Backboned Animals, Especially Mammals. London: John Murray. pp. 427–9.

- ↑ Foley, C.; Foley, L.; Lobora, A.; De Luca, D.; Msuha, M.; Davenport, T.R.B.; Durant, S.M. (2014). A Field Guide to the Larger Mammals of Tanzania. China: Princeton University Press. pp. 122–3. ISBN 9780691161174.

- ↑ Briggs, P.; McIntyre, C. (2013). Tanzania Safari Guide : With Kilimanjaro, Zanzibar and the Coast (7th ed.). Chalfont St. Peter, Bucks: Bradt Travel Guides. p. 25. ISBN 9781841624624.

- 1 2 3 Russell, A.P.; Bryant, H.N. (2001). "Claw retraction and protraction in the Carnivora: the cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) as an atypical felid". Journal of Zoology 254 (1): 67–76. doi:10.1017/S0952836901000565.

- 1 2 Hunter, L.; Hinde, G. (2005). Cats of Africa : Behaviour, Ecology, and Conservation. Cape Town: Struik. pp. 1–172. ISBN 177007063X.

- ↑ Segura, V.; Prevosti, F.; Cassini, G. (2013). "Cranial ontogeny in the Puma lineage, Puma concolor, Herpailurus yagouaroundi, and Acinonyx jubatus (Carnivora: Felidae): a three-dimensional geometric morphometric approach". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 169 (1): 235–50. doi:10.1111/zoj.12047.

- ↑ Hast, M.H. (1989). "The larynx of roaring and non-roaring cats". Journal of Anatomy 163: 117–21. PMC 1256521.

- ↑ Georgiou, A. (2011). "The Predators". Namibia (3rd ed.). Singapore: APA Publications. ISBN 9789812823434.

- ↑ Londei, T. (2000). "The cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) dewclaw: specialization overlooked". Journal of Zoology (London: The Zoological Society of London) 251 (4): 535–47.

- ↑ Guggisberg, C. A. W. (1975). Wild Cats of the World. David and Charles, London.

- ↑ Marker, L. (1998). Current status of the cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus). In: Proceedings of a symposium on cheetahs as game ranch animals. South African Veterinary Association, Onderstepoort. Pp. 1–17.

- ↑ Farhadinia, M. S. (2004). "The last stronghold: cheetah in Iran". Cat News 40: 11–14.

- ↑ Jowkar, H., Hunter, L., Ziaie, H., Marker, L., Breitenmoser-Würsten, C. and Durant, S. (2008). "Acinonyx jubatus ssp. venaticus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2015.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature.

- ↑ Richard Estes, foreword by Edward Osborne Wilson (1991) The Behavior Guide to African Mammals. University of California Press. Page 371.

- 1 2 3 Caro, T. M. (1994). Cheetahs of the Serengeti Plains: Group Living in an Asocial Species. University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London. ISBN 978-0-226-09433-5.

- ↑ "Cheetah Information" (PDF). Cheetah Outreach. Retrieved 2015-03-06.

- ↑ MacMillan, Dianne. Cheetahs. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2013-03-30.

- ↑ Smithsonian Channel (October 24, 2014). "Cheetahs Fighting Cheetahs". youtube.com.

- 1 2 Robert Eklund; Gustav Peters; Florian Weise; Stuart Munro (2012). "An acoustic analysis of agonistic sounds in wild cheetahs" (PDF). FONETIK 2012, Department of Philosophy, Linguistics and Theory of Science, University of Gothenburg. Retrieved 2013-03-30.

- ↑ Robert Eklund. "Robert Eklund's Ingressive Phonation and Speech Page". Ingressivespeech.info. Retrieved 2013-03-30.

- ↑ Robert Eklund. "Robert Eklund's Wildlife Experience Page". Roberteklund.info. Retrieved 2013-03-30.

- ↑ Robert Eklund. "– The felid purring site". Purring.org. Retrieved 2013-03-30.

- ↑ Robert Eklund; Gustav Peters; Elizabeth D. Duthie. "An acoustic analysis of purring in the cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) and in the domestic cat (Felis catus)" (PDF). Roberteklund.info. Retrieved 2013-03-30.

- ↑ Robert Eklund; Gustav Peters; Florian Weise; Stuart Munro (2012). "A comparative acoustic analysis of purring in four cheetahs" (PDF). FONETIK 2012, Department of Philosophy, Linguistics and Theory of Science, University of Gothenburg. Retrieved 2013-03-30.

- ↑ Robert Eklund; Gustav Peters. "A comparative acoustic analysis of purring in juvenile, subadult and adult cheetahs" (PDF). Proceedings of Fonetik 2013, the XXVIth Swedish Phonetics Conference held at Linköping University, 12–13 June 2013. Retrieved 2013-03-30.

- ↑ Hayward, M. W. Hofmeyr, M., O'Brien, J. and G. I. H. Kerley (2006). "Prey preferences of the cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) (Felidae: Carnivora): morphological limitations or the need to capture rapidly consumable prey before kleptoparasites arrive?". Journal of Zoology 270 (4): 615. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2006.00184.x.

- ↑ Farhadinia, M. S., Hosseini-Zavarei, F., Nezami, B., Harati, H., Absalan, H., Fabiano, E., and Marker, L. (2012). "Feeding ecology of the Asiatic cheetah Acinonyx jubatus venaticus in low prey habitats in northeastern Iran: Implications for effective conservation". Journal of Arid Environments 87: 206–211.

- ↑ Hunter, Luke and Hamman, Dave 2003, p. 96.

- 1 2 Sunquist & Sunquist 2002, p. 26.

- 1 2 3 4 O'Brien, S.; M. B., D. Wildt (1986). "The Cheetah in genetic peril". Scientific American 254: 68–76.

- ↑ Lee, Jane J. (23 July 2013). "Long-Held Myth About Cheetahs Busted". nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ↑ Schaller, G. B. (1968). "Hunting behaviour of the cheetah in the Serengeti National Park, Tanzania". East African Wildlife Journal 6: 95–100.

- 1 2 Ghosh, Pallab (12 June 2013). "Cheetah tracking study reveals incredible acceleration". BBC News. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ↑ Carwardine, M. (2008). Animal Records. New York: Sterling. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-4027-5623-8.

- ↑ Sears, E. S. (2001). Running Through the Ages. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-7864-0971-6.

- ↑ Smith, R. (2012). "Cheetah Breaks Speed Record—Beats Usain Bolt by Seconds". National Geographic Daily News (National Geographic Society).

- ↑ "Speed sensation". Nature Video Collections. BBC Nature.

- ↑ Sharp, N. C. (1997). "Timed running speed of a cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus)". Journal of Zoology, London 241 (3): 493–494. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1997.tb04840.x.

- ↑ Hildebrand, M. (1959). "Motions of Cheetah and Horse". Journal of Mammalogy 40 (4): 481–95. JSTOR 1376265.

- ↑ Gonyea, W.J. (1978). "Functional implications of felid forelimb anatomy". Acta Anatomica 102 (2): 111–21. PMID 685643.

- ↑ Hudson, P. E.; Corr, S. A.; Payne-Davis, R.C.; Clancy, S. N.; Lane, E.; Wilson, A. M. (April 2011). "Functional anatomy of the cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) hindlimb". Journal of Anatomy 218 (4): 363–74. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01310.x.

- ↑ Stuart, C.; Stuart, T. (2001). Field Guide to Mammals of Southern Africa (3rd ed.). Cape Town: Struik. p. 156. ISBN 1868725375.

- ↑ "Agility, Not Speed, Puts Cheetahs Ahead". Science 340: 1271. 2013. doi:10.1126/science.340.6138.1271-b.

- ↑ Wilson et al. 2013, p. 1.

- ↑ Alexander, R.M. (1993). "Legs and locomotion of Carnivora". Symposia of the Zoological Society of London 65: 1–13.

- 1 2 Hildebrand, M. (1961). "Further studies on locomotion of the cheetah". Journal of Mammalogy 42 (1): 84–96. doi:10.2307/1377246.

- ↑ Sharp 1997.

- ↑ Hudson, Corr & Wilson 2012, p. 2425.

- ↑ "Pronghorn Antilocapra americana". National Geographic. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ↑ Burton, M.; Burton, R. (2002). International Wildlife Encyclopedia (3rd ed.). New York: Marshall Cavendish. p. 226. ISBN 9780761472667.

- ↑ RVC Press Office (2013). "Groundbreaking RVC research shows wild cheetah reaching speeds of up to 58mph during a hunt". Royal Veterinary College, University of London. Retrieved 2013-06-16.

- ↑ Wilson et al. 2013.

- ↑ Bertram, J. E.A.; Gutmann, A. (2009). "Motions of the running horse and cheetah revisited: fundamental mechanics of the transverse and rotary gallop". Journal of The Royal Society Interface 6 (35): 549–59. doi:10.1098/rsif.2008.0328.

- ↑ Taylor, M.E. (1989). "Carnivore Behavior, Ecology, and Evolution". Locomotor Adaptations by Carnivores. USA: Springer. pp. 382–409. ISBN 9781461282044.

- ↑ Mares, M.A. (1999). Encyclopedia of Deserts. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 111. ISBN 9780806131467.

- ↑ Chinery, M. (1979). "Killers of the wild: Streamlined cheetah". Wildlife 21 (8): 6–7.

- ↑ Marker, L. (2002). Aspects of Namibian Cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) Biology, Ecology and Conservation Strategies. PhD. Thesis, Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, United Kingdom.

- ↑ Kelly, M. J., Laurenson, M. K., FitzGibbon, C. D., Collins, D. A., Durant, S. M., Frame, G. W., Bertram, B. C. R., Caro, T. M. (1998). "Demography of the Serengeti cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) population: the first 25 years". Journal of Zoology 244 (04): 473–488.

- ↑ Gottelli, D., Wang, J., Bashir, S., and Durant, S. M. (2007). "Genetic analysis reveals promiscuity among female cheetahs". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 274 (1621): 1993–2001.

- ↑ Eaton, R. L. (1976). "A Possible Case of Mimicry in Larger Mammals". Evolution 30 (4): 853–856 doi 10.2307/2407827

- ↑ Laurenson, M. K. (1994). "High juvenile mortality in cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus) and its consequences for maternal care". Journal of Zoology 234 (3): 387–408.

- ↑ Mills & Mills 2014.

- ↑ "Cheetah". Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ↑ Mitchell N., Tricorache P., Groom, R., Marker, L. and Durant, S. The Illegal Trade in Cheetahs. Poster. International Wildlife Trafficking Symposium. London, UK. February 2014.

- ↑ Voigt, C. C., Thalwitzer, S., Melzheimer, J., Blanc, A.-S., Jago, M., Wachter, B. (2014). "The conflict between cheetahs and humans on Namibian farmland elucidated by stable isotope diet analysis". PLoS ONE 9 (8): e101917.

- ↑ "Human Wildlife Conflict". Retrieved 2015-03-06.

- ↑ Fieldsports Britain. "Fieldsports Britain : Rabbits with a cheetah in Essex, grouse and". fieldsportschannel.tv. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ↑ Gugliotta, Guy (February 2008). "Rare Breed". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2008-03-07.

- ↑ "Cheetah Race for Survival". Cheetah.org. Retrieved 2015-03-06.

- ↑ http://www.cites.org/sites/default/files/eng/com/sc/65/E-SC65-39.pdf

- ↑ Crosier, A. E., Henghali, J. N., Howard, J., Pukazhenthi, B. S., Terrell, K. A., Marker, L. and Wildt, D. "Improved Quality of Cryopreserved Cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) Spermatozoa After Centrifugation Through Accudenz". Journal of Andrology, Vol. 30, No. 3, May/June 2009

- ↑ "Cheetah Metapopulation Project". CheetahPopulation.org.za. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ↑ "Facilitation of the Managed Cheetah Metapopulation". ewt.org.za. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ↑ "Wild cheetahs return to the Free State". SouthAfrica.info. 25 June 2013. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ↑ "Cheetahs Return to Laohu Valley Reserve & The Free State". Savechinastigers.org. Archived from the original on March 20, 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ↑ The Times of India, Thursday, July 9, 2009, p. 11.

- ↑ "| Travel India Guide". Binoygupta.com. 18 May 2012. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ↑ "Breaking: India's Plan to Re-Introduce the Cheetah on Hold". cheetah-watch.com. 8 May 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

Sources

- Allsen, Thomas T. (2006). "Natural History and Cultural History: The Circulation of Hunting Leopards in Eurasia, Seventh-Seventeenth Centuries". In Victor H. Mair, ed., Contact and Exchange in the Ancient World, pp. 116–135. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2884-4.

- Eklund, Robert and Gustav Peters. 2013. "A comparative acoustic analysis of purring in juvenile, subadult and adult cheetahs". in Robert Eklund (editor.), Proceedings of Fonetik 2013, the XXVIth Swedish Phonetics Conference, Studies in Language and Culture, no. 21, ISBN 978-91-7519-582-7, ISBN 978-91-7519-579-7, ISSN 1403-2570, pp. 25–28.

- Eklund, Robert, Gustav Peters and Elizabeth D. Duthie. 2010 (third edition). "An acoustic analysis of purring in the cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) and in the domestic cat (Felis catus)". Proceedings of Fonetik 2010, Lund University, 2–4 June 2010, Lund, Sweden, pp. 17–22. Download from or .

- Hudson, P. E.; Corr, S. A.; Wilson, A. M. (2012). "High speed galloping in the cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) and the racing greyhound (Canis familiaris): spatio-temporal and kinetic characteristics" (PDF). The Journal of Experimental Biology 215 (14): 2425–2434. doi:10.1242/jeb.066720.

- Hunter, Luke; Hamman, Dave (2003). Cheetah. Struik Publishers. ISBN 1-86872-719-X.

- Kaelin, C. B.; Xu, X.; Hong, L. Z.; David, V. A.; McGowan, K. A.; Schmidt-Küntzel, A.; Roelke, M. E.; Pino, J.; Pontius, J.; Cooper, G. M.; Manuel, H.; Swanson, W. F.; Marker, L.; Harper, C. K.; van Dyk, A.; Yue, B.; Mullikin, J. C.; Warren, W. C.; Eizirik, E.; Kos, L.; O'Brien, S. J.; Barsh, G. S.; Menotti-Raymond, M. (2012). "Specifying and Sustaining Pigmentation Patterns in Domestic and Wild Cats". Science 337 (6101): 1536–1541. doi:10.1126/science.1220893. PMID 22997338.

- Mills, Gus (1998). Big Cats and Other African Carnivores. Struik. ISBN 1-86825-920-X.

- Mills, Gus; Harvey, Martin (2001). African Predators. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books. ISBN 978-1-560-98096-4.

- Mills, M. G. L.; Mills, M. E. J. (2014). "Cheetah cub survival revisited: a re‐evaluation of the role of predation, especially by lions, and implications for conservation". Journal of Zoology 292 (2): 136–141. doi:10.1111/jzo.12087/.

- Scott, Jonathan; Scott, Angela (2005). Cheetah (Big Cat Diary). HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-714920-4.

- Sharp, N. C. C. (1997). "Timed running speed of a cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus)". Journal of Zoology 241 (3): 493–494. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1997.tb04840.x.

- Sunquist, Mel; Sunquist, Fiona (2002). Wild Cats of the World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-77999-7.

- Wilson, A. M.; Lowe, J. C.; Roskilly, K.; Hudson, P. E.; Golabek, K. A.; McNutt, J. W. (2013). "Locomotion dynamics of hunting in wild cheetahs". Nature 498 (7453): 185–189. doi:10.1038/nature12295. PMID 23765495.

- Wilson, J. W.; Mills, M. G. L.; Wilson, R. P.; Peters, G.; Mills, M. E. J.; Speakman, J. R.; Durant, S. M.; Bennett, N. C.; Marks, N. J.; Scantlebury, M. (2013). "Cheetahs, Acinonyx jubatus, balance turn capacity with pace when chasing prey". Biology Letters 9 (5). doi:10.1098/rsbl.2013.0620.

Further reading

- Caro, T. M. (1994). Cheetahs of the Serengeti Plains: group living in an asocial species. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-09433-2.

- Great Cats, Majestic Creatures of the Wild, ed. John Seidensticker, illus. Frank Knight, (Rodale Press, 1991), ISBN 0-87857-965-6

- Cheetah, Katherine (or Kathrine) and Karl Ammann, Arco Pub, (1985), ISBN 0-668-06259-2.

- Science (vol 311, p. 73)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Acinonyx jubatus. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Acinonyx jubatus |

- Species portrait Cheetah; IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group

- Cheetah at the Encyclopedia of Life

- Biodiversity Heritage Library bibliography for Acinonyx jubatus

- Cheetah Conservation Fund

- Save China's Tigers to Fund Wild Cat Conservation Worldwide

- De Wildt Cheetah and Wildlife Trust

- On the Chase With Cheetahs - slideshow by Life magazine

- Fake Flies and Cheating Cheetahs: measuring the speed of a cheetah

- Mutant Cheetahs: information on color variants of cheetahs

|

.jpg)