First Anglo-Afghan War

| First Anglo-Afghan War | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Great Game | |||||

A British-Indian force attacks Ghazni fort during the First Afghan War, c.1839. | |||||

| |||||

| Belligerents | |||||

|

| |||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||

|

|

| ||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||

|

~500 soldiers | 4,700 soldiers + 12,000 camp followers[1] | ||||

The First Anglo-Afghan War (also known as Auckland's Folly) was fought between the British East India Company and Afghanistan from 1839 to 1842, and ended in an overall Afghan victory.[2][3][4][5][6] It is famous for the killing of 4,500 British and Indian soldiers, plus 12,000 of their camp followers, by Afghan tribal fighters, but the British defeated the Afghans in the concluding engagement.[1] It was one of the first major conflicts during the Great Game, the 19th century competition for power and influence in Asia between the United Kingdom and the Russian Empire.[7]

Causes

In the 1830s the British Empire was firmly entrenched in India, but by 1837 Lord Palmerston and John Hobhouse, fearing the instability of Afghanistan, the Sindh, and the increasing power of the Sikh kingdom to the northwest, raised the spectre of a possible Russian invasion of India through Afghanistan. The Russian Empire was slowly extending its domain into Central Asia, and this was seen as an encroachment south that might prove fatal for the British Company rule in India. The British sent an envoy to Kabul to form an alliance with Afghanistan's Amir, Dost Mohammad Khan against Russia.[8][9]

Dost Mohammad had recently lost Afghanistan's second capital of Peshawar to the Sikh Empire and wanted support to retake it, but the British were unwilling. When Governor-General of India Lord Auckland heard about the arrival of Russian envoy Yan Vitkevich in Kabul and the possibility that Dost Mohammad might turn to Russia for support, his political advisers exaggerated the threat.[7] British fears of a Russian invasion of India took one step closer to becoming a reality when negotiations between the Afghans and Russians broke down in 1838. The Qajar dynasty of Persia, with Russian support, attempted the Siege of Herat (1838) but backed down when Britain threatened war.

Russia, wanting to increase its presence in South and Central Asia, had formed an alliance with Qajar Persia, which had territorial disputes with Afghanistan as Herat had been part of the Safavid Persia before 1709. Lord Auckland's plan was to drive away the besiegers and replace the ruler of Afghanistan with one who was pro-British, Shuja Shah Durrani.

The British denied that they were invading Afghanistan, claiming they were merely supporting its "legitimate" Shuja government "against foreign interference and factious opposition."[1]

British Indian invasion of Afghanistan

An army of 21,000 British and Indian troops under the command of John Keane, 1st Baron Keane (subsequently replaced by Sir Willoughby Cotton and then by William Elphinstone) set out from Punjab in December 1838. With them was William Hay Macnaghten, the former chief secretary of the Calcutta government, who had been selected as Britain's chief representative to Kabul. By late March 1839 the British forces had crossed the Bolan Pass, reached the Baloch city of Quetta, and begun their march to Kabul. They advanced through rough terrain, across deserts and 4,000-metre-high mountain passes, but made good progress and finally set up camps at Kandahar on 25 April 1839.

On 22 July 1839, in a surprise attack, the British-led forces captured the fortress of Ghazni, which overlooks a plain leading eastward into the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. The British troops blew up one city gate and marched into the city in a euphoric mood. In taking this fortress, they suffered 200 men killed and wounded, while the Afghans lost nearly 500 men. 1,600 Afghans were taken prisoner with an unknown number wounded. Ghazni was well-supplied, which eased the further advance considerably.

Following this, the British achieved a decisive victory over Dost Mohammad's troops, led by one of his sons. Dost Mohammad fled with his loyal followers across the passes to Bamyan, and ultimately to Bukhara. In August 1839, after thirty years, Shuja was again enthroned in Kabul.

Qalat/Kalat

On November 13, 1839, while en route to India, the Bombay column of the British Indian Army attacked, as a form of reprisal, the Baloch tribal fortress of Kalat,[10] from where Baloch tribes had harassed and attacked British convoys during the move towards the Bolan Pass.

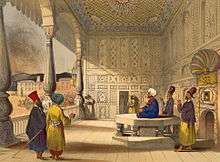

Occupation and rise of the Afghans

The majority of the British troops returned to India, leaving 8,000 in Afghanistan, but it soon became clear that Shuja's rule could only be maintained with the presence of a stronger British force. The Afghans resented the British presence and the rule of Shah Shuja. As the occupation dragged on, William Hay Macnaghten allowed his soldiers to bring their families to Afghanistan to improve morale;[11] this further infuriated the Afghans, as it appeared the British were setting up a permanent occupation. Dost Mohammad unsuccessfully attacked the British and their Afghan protégé, and subsequently surrendered and was exiled to India in late 1840.

By this time, the British had vacated the fortress of Bala Hissar and relocated to a cantonment built to the northeast of Kabul. The chosen location was indefensible, being low and swampy with hills on every side. To make matters worse, the cantonment was too large for the number of troops camped in it and had a defensive perimeter almost two miles long. In addition, the stores and supplies were in a separate fort, 300 yards from the main cantonment.[12]

Between April and October 1841, disaffected Afghan tribes were flocking to support Dost Mohammad's son, Akbar Khan, in Bamiyan and other areas north of the Hindu Kush mountains, organised into an effective resistance by chiefs such as Mir Masjidi Khan[13] and others. In November 1841, a senior British officer, Sir Alexander 'Sekundar' Burnes, and his aides were killed by a mob in Kabul. The British forces took no action in response, which encouraged further revolt. The British situation soon deteriorated when Afghans stormed the poorly defended supply fort inside Kabul on November 9.

In the following weeks the British commanders tried to negotiate with Akbar Khan. Macnaghten secretly offered to make Akbar Afghanistan's vizier in exchange for allowing the British to stay, while simultaneously disbursing large sums of money to have him assassinated, which was reported to Akbar Khan. A meeting for direct negotiations between Macnaghten and Akbar was held near the cantonment on 23 December, but Macnaghten and the three officers accompanying him were seized and slain by Akbar Khan. Macnaghten's body was dragged through the streets of Kabul and displayed in the bazaar. Elphinstone had partly lost command of his troops already and his authority was badly damaged.

Destruction of Elphinstone's army

On 1 January 1842, following some unusual thinking by Elphinstone, which may have had something to do with the poor defensibility of the cantonment, an agreement was reached that provided for the safe exodus of the British garrison and its dependants from Afghanistan.[14] Five days later, the withdrawal began. The departing British contingent numbered around 16,500, of which about 4,500 were military personnel, and over 12,000 were camp followers. The military force consisted mostly of Indian units and one British battalion, 44th Regiment of Foot.

They were attacked by Ghilzai warriors as they struggled through the snowbound passes. The evacuees were killed in huge numbers as they made their way down the 30 miles (48 km) of treacherous gorges and passes lying along the Kabul River between Kabul and Gandamak, and were massacred at the Gandamak pass before a survivor reached the besieged garrison at Jalalabad. The force had been reduced to fewer than forty men by a withdrawal from Kabul that had become, towards the end, a running battle through two feet of snow. The ground was frozen, the men had no shelter and had little food for weeks. Of the weapons remaining to the survivors, there were approximately a dozen working muskets, the officers' pistols and a few swords. The remnants of the 44th were all killed except Captain James Souter, Sergeant Fair and seven soldiers who were taken prisoner.[15] The only soldier to reach Jalalabad was Dr. William Brydon.

Reprisals

At the same time as the attacks on the garrison at Kabul, Afghan forces beleaguered the other British contingents in Afghanistan. These were at Kandahar (where the largest British force in the country had been stationed), Jalalabad (held by a force which had been sent from Kabul in October 1841 as the first stage of a planned withdrawal) and Ghazni. Ghazni was stormed, but the other garrisons held out until relief forces arrived from India, in spring 1842. Akbar Khan was defeated near Jalalabad and plans were laid for the recapture of Kabul and the restoration of British hegemony.

However, Lord Auckland had suffered a stroke and had been replaced as governor-general by Lord Ellenborough, who was under instructions to bring the war to an end following a change of government in Britain. Ellenborough ordered the forces at Kandahar and Jalalabad to leave Afghanistan after inflicting reprisals and securing the release of prisoners taken during the retreat from Kabul.

In August 1842 General Nott advanced from Kandahar, pillaging the countryside and seizing Ghazni, whose fortifications he demolished. Meanwhile, General Pollock, who had taken command of a demoralized force in Peshawar used it to clear the Khyber Pass to arrive at Jalalabad, where General Sale had already lifted the siege. From Jalalabad, General Pollock inflicted a further crushing defeat on Akbar Khan. The combined British forces defeated all opposition before taking Kabul in September. A month later, having rescued the prisoners and demolished the city's main bazaar as an act of retaliation for the destruction of Elphinstone's column, they withdrew from Afghanistan through the Khyber Pass. Dost Muhammad was released and re-established his authority in Kabul. He died on June 9, 1863.

Legacy

Many voices in Britain, from Lord Aberdeen[16] to Benjamin Disraeli, had criticized the war as rash and insensate. The perceived threat from Russia was vastly exaggerated, given the distances, the almost impassable mountain barriers, and logistical problems that an invasion would have to solve. In the three decades after the First Anglo-Afghan War, the Russians did advance steadily southward towards Afghanistan. In 1842 the Russian border was on the other side of the Aral Sea from Afghanistan; but five years later the tsar's outposts had moved to the lower reaches of the Amu Darya. By 1865 Tashkent had been formally annexed, as was Samarkand three years later. A peace treaty in 1873 with Amir Alim Khan of the Manghit Dynasty, the ruler of Bukhara, virtually stripped him of his independence. Russian control then extended as far as the northern bank of the Amu Darya.

In 1878, the British invaded again, beginning the Second Anglo-Afghan War.

Lady Butler's famous painting of Dr. William Brydon, initially thought to be the sole survivor, gasping his way to the British outpost in Jalalabad, helped make Afghanistan's reputation as a graveyard for foreign armies and became one of the great epics of empire.

In 1843 British army chaplain G.R. Gleig wrote a memoir of the disastrous (First) Anglo-Afghan War, of which he was one of the very few survivors. He wrote that it was

a war begun for no wise purpose, carried on with a strange mixture of rashness and timidity, brought to a close after suffering and disaster, without much glory attached either to the government which directed, or the great body of troops which waged it. Not one benefit, political or military, was acquired with this war. Our eventual evacuation of the country resembled the retreat of an army defeated”.[17]

The Church of St. John the Evangelist located in Navy Nagar, Mumbai, India, more commonly known as the Afghan Church, was dedicated in 1852 as a memorial to the dead of the conflict.

Battle honour

The battle honour of 'Afghanistan 1839' was awarded to all units of the presidency armies of the East India Company that had proceeded beyond the Bolan Pass, by gazette of the governor-general, dated 19 November 1839, the spelling changed from 'Afghanistan' to 'Affghanistan' by Gazette of India No. 1079 of 1916, and the date added in 1914. All the honours awarded for this war are considered to be non-repugnant. The units awarded this battle honour were:

- 4th Bengal Irregular Cavalry – 1 Horse

- 5th Madras Infantry

- Poona Auxiliary Horse – Poona Horse

- Bombay Sappers & Miners – Bombay Engineer Group

- 31st Bengal Infantry

- 43rd Bengal Infantry

- 19th Bombay Infantry

- 1st Bombay Cavalry – 13th Lancers

- 2nd, 3rd Bengal Cavalry – mutinied in 1857.

- 2nd, 3rd Companies of Bengal Sappers and Miners – mutinied in 1857.

- 16th, 35th, 37th, 48th Bengal Infantry – mutinied in 1857.

- 42nd Bengal Infantry (5th LI) – disbanded 1922.

Fictional depictions

- The First Anglo–Afghan war is depicted in a work of historical fiction, Flashman by George MacDonald Fraser. (This is Fraser's first Flashman novel.) The ordeal of Dr. Brydon may have influenced the story of Dr. John Watson in Sherlock Holmes, although his wound was suffered in the second war.

- Emma Drummond's novel Beyond all Frontiers (1983) is based on these events, as are Philip Hensher's Mulberry Empire (2002) and Fanfare (1993), by Andrew MacAllan, a distant relation of Dr William Brydon.

- G.A. Henty's children's novel To Herat and Kabul focuses on the Anglo-Afghan War through the perspective of a Scottish expatriate teenager named Angus. Theodor Fontane's poem, Das Trauerspiel von Afghanistan (The Tragedy of Afghanistan) also refers to the massacre of Elphinstone’s army.[18]

See also

- Military history of Britain

- Military history of Afghanistan

- Chapslee Estate

- European influence in Afghanistan

- Invasions of Afghanistan

- Second Anglo-Afghan War

- Third Anglo-Afghan War

References

- 1 2 3 Baxter, Craig. "The First Anglo–Afghan War". In Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. Afghanistan: A Country Study. Baton Rouge, LA: Claitor's Pub. Division. ISBN 1-57980-744-5. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ↑ Shultz, Richard H.; Dew, Andrea J. (2006-08-22). Insurgents, Terrorists, and Militias: The Warriors of Contemporary Combat. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231503426.

- ↑ Toorn, Wout van der (2015-03-17). Logbook of the Low Countries (in Arabic). Page Publishing Inc. ISBN 9781634179997.

- ↑ Henshall, Kenneth (2012-03-13). A History of Japan: From Stone Age to Superpower. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780230369184.

- ↑ Little, David; Understanding, Tanenbaum Center for Interreligious (2007-01-08). Peacemakers in Action: Profiles of Religion in Conflict Resolution. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521853583.

- ↑ Steele, Jonathan (2011-01-01). Ghosts of Afghanistan: Hard Truths and Foreign Myths. Counterpoint Press. ISBN 9781582437873.

- 1 2 Keay, John (2010). India: A History (revised ed.). New York, NY: Grove Press. pp. 418–9. ISBN 978-0-8021-4558-1.

- ↑ L. W. Adamec/J. A. Norris, ANGLO-AFGHAN WARS, in Encyclopædia Iranica, online ed., 2010

- ↑ J.A. Norris, ANGLO-AFGHAN RELATIONS, in Encyclopædia Iranica, online ed., 2010

- ↑ Holdsworth, T W E (1840). Campaign of the Indus: In a Series of Letters from an Officer of the Bombay Division. Private Copy. Retrieved 2014-11-25.

- ↑ Dupree, L. Afghanistan. Princeton: Princeton Legacy Library, 1980. Pg. 379

- ↑ David, Saul. Victoria's Wars, 2007 Penguin Books. p. 41

- ↑ Who after his demise in 1841, was replaced by his son Mir Aqa Jan, see Maj (r) Nur Muhammad Shah, Kohistani, Nur i Kohistan, Lahore, 1957, pp. 49–52

- ↑ Macrory, Patrick. "Retreat From Kabul: The Catastrophic Defeat In Afghanistan, 1842". 2002 The Lyons Press p. 203

- ↑ Blackburn, Terence R. (2008). The extermination of a British army: the retreat from Cabul. New Delhi: A.P.H. Publishing Corporation. p. 121

- ↑ 'no man could say, unless it were subsequently explained, this course was not as rash and impolitic, as it was ill-considered, oppressive, and unjust.' Hansard, 19 March 1839.

- ↑ Gleig, George R. Sale's Brigade In Afghanistan, John Murray, 1879, p. 181.

- ↑ The Tragedy of Afghanistan, Retrieved 2013-08-21.

Further reading

- Dalrymple, William, (2012) Return of a King: the battle for Afghanistan, London: Bloomsbury.

- Fowler, Corinne, (2007) Chasing Tales: Travel Writing, Journalism and the History of British Ideas about Afghanistan, Amsterdam: Rodopi.

- Greenwood, Joseph, (1844) Narrative of the Late Victorious Campaign in Affghanistan, under General Pollock: With Recollections of Seven Years' service in India. London: H. Colburn

- Hopkirk, Peter, (1992) The Great Game, New York, NY: Kodansha America, ISBN 1-56836-022-3

- Kaye, Sir John, (1860) History of the First Afghan War, London.

- Macrory, Patrick, (1966) The Fierce Pawns, J.B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia

- Macrory, Patrick, (2002) Retreat from Kabul: The Catastrophic British Defeat in Afghanistan, 1842. Guilford, CT: The Lyons Press. ISBN 978-1-59921-177-0

- Morris, Mowbray. The First Afghan War. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington (1878).

- Perry, James M., (1996), Arrogant Armies: Great Military Disasters and the Generals Behind Them. New York:Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-11976-0

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to First Anglo-Afghan War. |

- First Afghan War (Battle of Ghuznee)

- First Afghan War (Battle of Kabul 1842)

- The Siege of Jellalabad

- First Afghan War (Battle of Kabul and retreat to Gandamak)

- The Afghan Wars 1839–42 and 1878–80 by Archibald Forbes, from Project Gutenberg

- Pictures of the First Anglo–Afghan War

- The War of Kabul and Kandahar, circa 1850

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||