Affine space

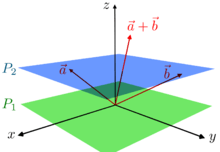

is a vector subspace of

is a vector subspace of  , this is not true for the upper (blue) plane

, this is not true for the upper (blue) plane  : For any two vectors

: For any two vectors  we find

we find  . However,

. However,  is a simple example of an affine space. The difference

is a simple example of an affine space. The difference  of two of its elements lies in

of two of its elements lies in  and constitutes a displacement vector.

and constitutes a displacement vector.

In mathematics, an affine space is a geometric structure that generalizes the properties of Euclidean spaces that are independent of the concepts of distance and measure of angles, keeping only the properties related to parallelism and ratio of lengths for parallel line segments. A Euclidean space is an affine space over the reals, equipped with a metric, the Euclidean distance. Therefore, in Euclidean geometry, an affine property is a property that may be proved in affine spaces.

In an affine space, there is no distinguished point that serves as an origin. Hence, no vector has a fixed origin and no vector can be uniquely associated to a point. In an affine space, there are instead displacement vectors, also called translation vectors or simply translations, between two points of the space.[1] Thus it makes sense to subtract two points of the space, giving a translation vector, but it does not make sense to add two points of the space. Likewise, it makes sense to add a vector to a point of an affine space, resulting in a new point translated from the starting point by that vector.

Any vector space may be considered as an affine space, and this amounts to forgetting the special role played by the zero vector. In this case, the elements of the vector space may be viewed either as points of the affine space or as displacement vectors or translations. When considered as a point, the zero vector is called the origin. Adding a fixed vector to the elements of a linear subspace of a vector space produces an affine subspace. One commonly says that this affine subspace has been obtained by translating (away from the origin) the linear subspace by the translation vector. In finite dimensions, such an affine subspace is the solution set of an inhomogeneous linear system. The displacement vectors for that affine space are the solutions of the corresponding homogeneous linear system, which is a linear subspace. Linear subspaces, in contrast, always contain the origin of the vector space.

The dimension of an affine space is defined as the dimension of the vector space of its translations. An affine space of dimension one is an affine line. An affine space of dimension 2 is an affine plane. An affine subspace of dimension n – 1 in an affine space or a vector space of dimension n is a affine hyperplane.

Informal description

The following characterization may be easier to understand than the usual formal definition: an affine space is what is left of a vector space after you've forgotten which point is the origin (or, in the words of the French mathematician Marcel Berger, "An affine space is nothing more than a vector space whose origin we try to forget about, by adding translations to the linear maps"[2]). Imagine that Alice knows that a certain point is the actual origin, but Bob believes that another point — call it p — is the origin. Two vectors, a and b, are to be added. Bob draws an arrow from point p to point a and another arrow from point p to point b, and completes the parallelogram to find what Bob thinks is a + b, but Alice knows that he has actually computed

- p + (a − p) + (b − p).

Similarly, Alice and Bob may evaluate any linear combination of a and b, or of any finite set of vectors, and will generally get different answers. However, if the sum of the coefficients in a linear combination is 1, then Alice and Bob will arrive at the same answer.

If Bob travels to

- λa + (1 − λ)b

then Alice can similarly travel to

- p + λ(a − p) + (1 − λ)(b − p) = λa + (1 − λ)b.

Then, for all coefficients λ + (1 − λ) = 1, Alice and Bob describe the same point with the same linear combination, starting from different origins.

While Alice knows the "linear structure", both Alice and Bob know the "affine structure"—i.e. the values of affine combinations, defined as linear combinations in which the sum of the coefficients is 1. An underlying set with an affine structure is an affine space.

Definition

An affine space[3] is a set A to which is associated a vector space  over a field k and a transitive and free action of the additive group of

over a field k and a transitive and free action of the additive group of  (That is, an affine space is a principal homogeneous space for the action of the additive group.)

(That is, an affine space is a principal homogeneous space for the action of the additive group.)

The elements of the affine space A are called points, and the elements of the associated vector space  are called vectors, "translations" or, sometimes free vectors.

are called vectors, "translations" or, sometimes free vectors.

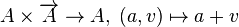

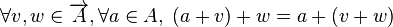

Explicitly, above definition means that one has a map, generally denoted as an addition,

which has the following properties:.[4][5][6]

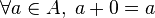

- Left identity

-

- Associativity

-

(here the last + is the addition of the vector space

(here the last + is the addition of the vector space  )

)

-

- Free and transitive action

- For every

the mapping

the mapping  is a bijection.

is a bijection.

- For every

These properties imply that for all  the mapping

the mapping  is also a bijection.

is also a bijection.

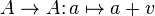

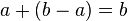

Subtraction and Weyl's axioms

The uniqueness property allows us to define the subtraction of any two elements a and b of A, producing a vector of  This vector, denoted

This vector, denoted

or

is the unique vector in  such that

such that  (equivalently,

(equivalently,  ).

).

This subtraction has the two following properties, called Weyl's axioms.[7]

-

there is a unique point

there is a unique point  such that

such that  (equivalently,

(equivalently,  ), and

), and -

(equivalently,

(equivalently,  ).

).

Affine spaces can be equivalently defined as a point set A, together with a vector space  and a subtraction satisfying Weyl's axioms. In this case, the addition of a vector to a point is defined from the first Weyl's axioms.

and a subtraction satisfying Weyl's axioms. In this case, the addition of a vector to a point is defined from the first Weyl's axioms.

In Euclidean geometry, the second Weyl's axiom is commonly called parallelogram rule.

Affine subspaces and parallelism

Let us consider an affine space A and its associated vector space

An affine subspace (also called, in some contexts, a linear variety, a flat, or, over the real numbers, a linear manifold) B of A is a subset of A such that the set of all differences of any two elements of B form a linear subspace  of

of  This implies that B is an affine space, which has

This implies that B is an affine space, which has  as associated vector space.

as associated vector space.

The linear subspace associated with an affine subspace is often called its direction, and two subspaces that share the same direction are said parallel.

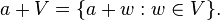

Given a linear subspace V of  the affine subspaces of direction V are the sets

the affine subspaces of direction V are the sets

This implies the following generalization of Playfair's axiom: Given a direction V, for any point of A there is one and only one affine subspace of direction V, which passes through the point.

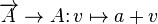

Given a vector  the map

the map

is called a translation. It maps any affine subspace to a parallel subspace.

The term parallel is also used for two affine subspaces such that the direction of one is included in the direction of the other.

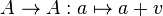

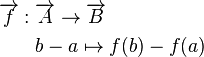

Affine map

Given two affine spaces A and B whose associated vector spaces are  and

and  an affine map or affine homomorphism from A to B is a map

an affine map or affine homomorphism from A to B is a map

such that

is a well defined linear map. (Here a and b belong to A, and "well defined" means that b – a = d – c implies f(b – a) = f(d – c).)

This implies that, for a point  and a vector

and a vector  one has

one has

Therefore, f is completely defined by its value on a single point and the associated linear map

Fundamental example

Every vector space V may be considered as an affine space over itself. This means that every element of V may be considered either as a point or as a vector. This affine set is sometimes denoted (V, V) for emphasizing the double role of the elements of V. When considered as a point, the zero vector is commonly denoted o (or O, when upper-case letters are used for points) and called the origin.

If A is another affine space over the same vector space (that is  ) the choice of any point a in A defines a unique affine isomorphism, which is the identity of V and maps a to o. In other words, the choice of an origin a in A allows to identify A and (V, V) up to a canonical isomorphism. The counterpart of this property is that the affine space A may be identified with the vector space V in which "the place of the origin has been forgotten".

) the choice of any point a in A defines a unique affine isomorphism, which is the identity of V and maps a to o. In other words, the choice of an origin a in A allows to identify A and (V, V) up to a canonical isomorphism. The counterpart of this property is that the affine space A may be identified with the vector space V in which "the place of the origin has been forgotten".

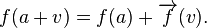

Affine combinations and barycenter

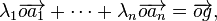

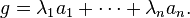

Let us consider, in an affine space, n points a1, ..., an, and n elements  of the ground field. For clarity, we denote

of the ground field. For clarity, we denote  the vector b – a.

the vector b – a.

If  for any two points o and o' one has

for any two points o and o' one has

Thus this sum is independent of the choice of the origin, and the resulting vector is denoted

In particular, when  one retrieve the definition of the subtraction of points.

one retrieve the definition of the subtraction of points.

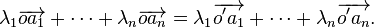

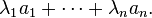

If  let us denote by

let us denote by  the unique point such that

the unique point such that

for some choice of an origin  One can show that

One can show that  is independent from the choice of the origin

is independent from the choice of the origin  Therefore, if

Therefore, if

one writes

The point  is called the barycenter of the

is called the barycenter of the  for the weights

for the weights  One says also that

One says also that  is an affine combination of the

is an affine combination of the  with coefficients

with coefficients

Examples

- When children find the answers to sums such as 4 + 3 or 4 − 2 by counting right or left on a number line, they are treating the number line as a one-dimensional affine space.

- Any coset of a subspace V of a vector space is an affine space over that subspace.

- If T is a matrix and b lies in its column space, the set of solutions of the equation T x = b is an affine space over the subspace of solutions of T x = 0.

- The solutions of an inhomogeneous linear differential equation form an affine space over the solutions of the corresponding homogeneous linear equation.

- Generalizing all of the above, if T : V → W is a linear mapping and y lies in its image, the set of solutions x ∈ V to the equation T x = y is a coset of the kernel of T , and is therefore an affine space over Ker T .

- The space of (linear) complementary subspaces of a vector subspace V in a vector space W is an affine space, over Hom(W/V,V). That is, if

is a short exact sequence of vector spaces, then the space of all splittings of the exact sequence naturally carries the structure of an affine space over Hom(X,V).

is a short exact sequence of vector spaces, then the space of all splittings of the exact sequence naturally carries the structure of an affine space over Hom(X,V).

Affine span and bases

For any subset X of an affine space A, there is a smallest affine subspace that contains it, called the affine span of X. It is the intersection of all affine subspaces containing X, and its direction is the intersection of the directions of the affine subspaces that contain X.

The affine span of X is the set of all (finite) affine combinations of points of X, and its direction is the linear span of the x - y for x and y in X. If one chooses a particular point x0, the direction of the affine span of X is also the linear span of the x – x0 for x in X.

One says also that the affine span of X is generated by X and that X is a generating set of its affine span.

A set X of points of an affine space is said affinely independent or, simply, independent, if the affine span of any strict subset of X is a strict subset of the affine span of X. An affine basis, or barycentric frame (see § Barycentric coordinates, below) of an affine space is a generating set that is also independent (that is a minimal generating set).

Recall the dimension of an affine space is the dimension of its associated vector space. The bases of an affine space of finite dimension n are the independent subsets of n + 1 elements, or, equivalently, the generating subsets of n + 1 elements. Equivalently, {x0, ..., xn} is an affine basis of an affine space if and only {x1 - x0, ..., xn - x0} is a linear basis of the associated vector space.

Coordinates

There are two strongly related kinds of coordinate systems that may be defined on affine spaces.

Barycentric coordinates

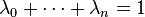

Let A be an affine space over a field k of dimension n, and  be an affine basis of A. The properties of an affine basis imply that for every x in A there is a unique (n+1)-tuple

be an affine basis of A. The properties of an affine basis imply that for every x in A there is a unique (n+1)-tuple  of elements of k such that

of elements of k such that

and

The  are called the barycentric coordinates of x over the affine basis

are called the barycentric coordinates of x over the affine basis  If the xi are viewed as bodies that have weights (or masses)

If the xi are viewed as bodies that have weights (or masses)  the point x is thus the barycenter of the xi, and this explains the origin of the term barycentric coordinates.

the point x is thus the barycenter of the xi, and this explains the origin of the term barycentric coordinates.

The barycentric coordinates define an affine isomorphism between the affine space A and the affine subspace of kn+1 defined by the equation

For affine spaces of infinite dimension, the same definition applies, using only finite sums. This means that for each point, only a finite number of coordinates are non-zero.

Affine coordinates

An affine frame of an affine space consists of a point, called the origin, and a linear basis of the associated vector space. More precisely, for an affine space A with associated vector space  the origin o belongs to A, and the linear basis is a basis (v1, ..., vn) of

the origin o belongs to A, and the linear basis is a basis (v1, ..., vn) of  (for simplicity of the notation, we consider only the case of finite dimension, the general case is similar).

(for simplicity of the notation, we consider only the case of finite dimension, the general case is similar).

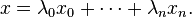

For each point p of A, there is a unique sequence  of elements of the ground field such that

of elements of the ground field such that

or equivalently

The  are called the affine coordinates of p over the frame (o, v1, ..., vn).

are called the affine coordinates of p over the frame (o, v1, ..., vn).

Example: In Euclidean geometry, Cartesian coordinates are affine coordinates relative to an orthonormal frame, that is an affine frame (o, v1, ..., vn) such that (v1, ..., vn) is an orthonormal basis.

Relationship between barycentric and affine coordinates

Barycentric coordinates and affine coordinates are strongly related, and may be considered as equivalent.

In fact, given a barycentric frame

one deduces immediately the affine frame

and, if

are the barycentric coordinates of a point over the barycentric frame, then the affine coordinates of the same point over the affine frame are

Conversely, if

is an affine frame, then

is a barycentric frame. If

are the affine coordinates of a point over the affine frame, then its barycentric coordinates over the barycentric frame are

Therefore, barycentric and affine coordinates are almost equivalent. In most applications, affine coordinates are preferred, as involving less coordinates that are independent. However, in the situations where the important points of the studied problem are affinity independent, barycentric coordinates may lead to simpler computation, as in the following example.

Example of the triangle

The vertices of a non-flat triangle form an affine basis of the Euclidean plane. The barycentric coordinates allows to characterize easily the elements of the triangle that do not involve angles or distance:

The vertices are the points of barycentric coordinates (1, 0, 0), (0, 1, 0) and (0, 0, 1). The lines supporting the edges are the points that have a zero coordinate. The edges themselves are the points that have a zero coordinate and two nonnegative coordinates. The interior of the triangle are the points whose all coordinates are positive. The medians are the points that have two equal coordinates, and the centroid is the point of coordinates (1/3, 1/3, 1/3).

Properties of affine homomorphisms

Image and fibers

Let

be an affine homomorphism.

The image of (f, g) is the affine subspace (f(E), g(V)) of (F, W). As an affine space does not have a zero element, an affine homomorphism does not have a kernel. However, for any point x of f(E), the inverse image f–1(x) of x is an affine subspace of E, of direction g–1(W). This affine subspace is called the fiber of x.

Projection

An important example is the projection parallel to some direction onto an affine subspace. The importance of this example lies in the fact that Euclidean spaces are affine spaces, and that this kind of projections is fundamental in Euclidean geometry.

More precisely, given an affine space E whose associated vector space is V, let F be an affine subspace of direction W, and D be a complementary subspace of W in V (this means that every vector of V may be decomposed in a unique way as the sum of an element of W and an element of D). For every point x of E, its projection to F parallel to D is the unique p(x) in F such that

This an affine homomorphism whose associated linear map q is defined by

The image of this projection is F, and its fibers are the subspaces of direction D.

Quotient space

Although kernels are not defined for affine space, quotient spaces are defined. This results from the fact that "belonging to the same fiber of an affine homomorphism" is an equivalence relation.

Let E be an affine space of associated vector space V, and D be a linear subspace. The quotient E/D of E by D is the quotient of E by the equivalence relation

This is an affine space, which has V/D as associated vector space.

For every affine homomorphism  , the image is isomorphic to the quotient of E by the kernel of the associated linear map. This is the first isomorphism theorem for affine spaces.

, the image is isomorphic to the quotient of E by the kernel of the associated linear map. This is the first isomorphism theorem for affine spaces.

Affine transformation

Axioms

Affine space is usually studied as analytic geometry using coordinates, or equivalently vector spaces. It can also be studied as synthetic geometry by writing down axioms, though this approach is much less common. There are several different systems of axioms for affine space.

Coxeter (1969, p. 192) axiomatizes affine geometry (over the reals) as ordered geometry together with an affine form of Desargues's theorem and an axiom stating that in a plane there is at most one line through a given point not meeting a given line.

Affine planes satisfy the following axioms (Cameron 1991, chapter 2): (in which two lines are called parallel if they are equal or disjoint):

- Any two distinct points lie on a unique line.

- Given a point and line there is a unique line which contains the point and is parallel to the line

- There exist three non-collinear points.

As well as affine planes over fields (or division rings), there are also many non-Desarguesian planes satisfying these axioms. (Cameron 1991, chapter 3) gives axioms for higher-dimensional affine spaces.

Relation to projective spaces

Affine spaces are subspaces of projective spaces: an affine plane can be obtained from any projective plane by removing a line and all the points on it, and conversely any affine plane can be used to construct a projective plane as a closure by adding a line at infinity whose points correspond to equivalence classes of parallel lines.

Further, transformations of projective space that preserve affine space (equivalently, that leave the hyperplane at infinity invariant as a set) yield transformations of affine space. Conversely, any affine linear transformation extends uniquely to a projective linear transformation, so the affine group is a subgroup of the projective group. For instance, Möbius transformations (transformations of the complex projective line, or Riemann sphere) are affine (transformations of the complex plane) if and only if they fix the point at infinity.

Affine algebraic geometry

In algebraic geometry, an affine variety (or, more generally, an affine algebraic set) is defined as the subset of an affine space that is the set of the common zeros of a set of so-called polynomial functions over the affine space. For defining a polynomial function over the affine space, one has to choose an affine coordinate system. Then, a polynomial function is a function such that the image of any point is the value of some multivariate polynomial function of the coordinates of the point. As a change of affine coordinates may be expressed by linear functions (more precisely affine functions) of the coordinates, this definition is independent of a particular choice of coordinates.

The choice of a system of affine coordinates for an affine space  of dimension n over a field k induces an affine isomorphism between

of dimension n over a field k induces an affine isomorphism between  and the affine coordinate space kn. This explain why, for simplification, many textbooks write

and the affine coordinate space kn. This explain why, for simplification, many textbooks write  , and introduce affine algebraic varieties as the common zeros of polynomial functions over kn.[8]

, and introduce affine algebraic varieties as the common zeros of polynomial functions over kn.[8]

As the whole affine space is the set of the common zeros of the zero polynomial, affine spaces are affine algebraic varieties.

Ring of polynomial functions

By the above definition, the choice of an affine coordinate system of an affine space space  allows to identify the polynomial functions on

allows to identify the polynomial functions on  with polynomials in n variables, the ith variable representing the function that maps a point to its ith coordinate. It follows that the set of polynomial functions over

with polynomials in n variables, the ith variable representing the function that maps a point to its ith coordinate. It follows that the set of polynomial functions over  is a k-algebra, denoted

is a k-algebra, denoted ![k[\mathbb A_k^n],](../I/m/bec0d6061bf06cbb73d4d52b023d0c50.png) which is isomorphic to the polynomial ring

which is isomorphic to the polynomial ring ![k[X_1, \ldots, X_n].](../I/m/3900a61e204dd7e31ee6bc7b524e43ca.png)

When one changes of coordinates, the isomorphism between ![k[\mathbb A_k^n]](../I/m/3dd4c1528efdf9bc09fb0a15366dfcd4.png) and

and ![k[X_1, \ldots, X_n]](../I/m/c901657f34686cd7c6d58c0019836751.png) changes accordingly, and this induces an automorphism of

changes accordingly, and this induces an automorphism of ![k[X_1, \ldots, X_n]](../I/m/c901657f34686cd7c6d58c0019836751.png) , which maps each indeterminate to a polynomial of degree one. It follows that the total degree defines a filtration of

, which maps each indeterminate to a polynomial of degree one. It follows that the total degree defines a filtration of ![k[\mathbb A_k^n],](../I/m/bec0d6061bf06cbb73d4d52b023d0c50.png) which is independent from the choice of coordinates. The total degree defines also a graduation, but it depends on the choice of coordinates, as a change of affine coordinates may map indeterminates on non-homogeneous polynomials.

which is independent from the choice of coordinates. The total degree defines also a graduation, but it depends on the choice of coordinates, as a change of affine coordinates may map indeterminates on non-homogeneous polynomials.

Zariski topology

Affine spaces over topological fields, such as the real or the complex numbers have a natural topology. The Zariski topology, which is defined for affine spaces over any field, allows to use topological methods in any case. Zariski topology is the unique topology on an affine space whose closed sets are affine algebraic sets (that is sets of the common zeros of polynomials functions over the affine set). As, over a topological field, polynomial functions are continuous, every Zariski closed set is closed for the usual topology, if any. In other words, over a topological field, Zariski topology is coarser than the natural topology.

There is a natural injective function from an affine space into the set of prime ideals (that is the spectrum) of its ring of polynomial functions. When affine coordinates have been chosen, this function maps the point of coordinates  to the maximal ideal

to the maximal ideal  This function is an homeomorphism (for the Zariski topology of the affine space and of the spectrum of the ring of polynomial functions) of the affine space onto the image of the function.

This function is an homeomorphism (for the Zariski topology of the affine space and of the spectrum of the ring of polynomial functions) of the affine space onto the image of the function.

The case of an algebraically closed ground field is specially important is algebraic geometry, because, in this case, the above homeomorphism is a homeomorphism between the affine space and the set of all maximal ideals of the ring of functions (this is Hilbert's Nullstellensatz).

This is the starting idea of scheme theory of Grothendieck, which consists, for studying algebraic varieties, of considering as "points", not only the points of the affine space, but also all the prime ideals of the spectrum. This allows gluing together algebraic varieties in a similar way as, for manifolds, charts are glued together for building a manifold.

Cohomology

Like all affine varieties, local data on an affine space can always be patched together globally: the cohomology of affine space is trivial. More precisely,  for all coherent sheaves F, and integers

for all coherent sheaves F, and integers  . This property is also enjoyed by all other affine varieties. But also all of the etale cohomology groups on affine space are trivial. In particular, every line bundle is trivial. More generally, the Quillen–Suslin theorem implies that every algebraic vector bundle over an affine space is trivial.

. This property is also enjoyed by all other affine varieties. But also all of the etale cohomology groups on affine space are trivial. In particular, every line bundle is trivial. More generally, the Quillen–Suslin theorem implies that every algebraic vector bundle over an affine space is trivial.

See also

- Space (mathematics)

- Affine geometry

- Affine group

- Affine transformation

- Affine variety

- Affine hull

- Heap (mathematics)

- Equipollence (geometry)

- Interval measurement, an affine observable in statistics

- Exotic affine space

- Complex affine space

Notes

- ↑ The word translation is generally preferred to displacement vector, which may be confusing, as displacements include also rotations.

- ↑ Berger 1987, p. 32

- ↑ Berger, Marcel (1984), "Affine spaces", Problems in Geometry, p. 11, ISBN 9780387909714

- ↑ Berger 1987, p. 33

- ↑ Snapper, Ernst; Troyer, Robert J. (1989), Metric Affine Geometry, p. 6

- ↑ Tarrida, Agusti R. (2011), "Affine spaces", Affine Maps, Euclidean Motions and Quadrics, pp. 1–2, ISBN 9780857297105

- ↑ Nomizu & Sasaki 1994, p. 7

- ↑ Hartshorne, Ch. I, § 1.

References

- Berger, Marcel (1984), "Affine spaces", Problems in Geometry, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-90971-4

- Berger, Marcel (1987), Geometry I, Berlin: Springer, ISBN 3-540-11658-3

- Cameron, Peter J. (1991), Projective and polar spaces, QMW Maths Notes 13, London: Queen Mary and Westfield College School of Mathematical Sciences, MR 1153019

- Coxeter, Harold Scott MacDonald (1969), Introduction to Geometry (2nd ed.), New York: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-471-50458-0, MR 123930

- Dolgachev, I.V.; Shirokov, A.P. (2001), "A/a011100", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- Snapper, Ernst; Troyer, Robert J. (1989), Metric Affine Geometry (Dover edition, first published in 1989 ed.), Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-66108-3

- Nomizu, K.; Sasaki, S. (1994), Affine Differential Geometry (New ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-44177-3

- Tarrida, Agusti R. (2011), "Affine spaces", Affine Maps, Euclidean Motions and Quadrics, Springer, ISBN 978-0-85729-709-9