Aérospatiale Gazelle

| SA 341/SA 342 Gazelle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Gazelle SA 342M of the French Army's Light Aviation (ALAT), Army's Helicopters Squadron (EHADT) | |

| Role | Utility helicopter / Armed helicopter |

| National origin | France |

| Manufacturer | Sud Aviation later Aérospatiale/Westland Aircraft/Soko |

| First flight | 7 April 1967 (SA.340) |

| Introduction | 1973 |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | French Army British Army Bosnian Air Force Egyptian Air Force Lebanese Air Force |

| Produced | 1967-1996 |

| Number built | 1,775 |

| Unit cost |

$198,500 (1973)[1] |

| Developed from | Aérospatiale Alouette III |

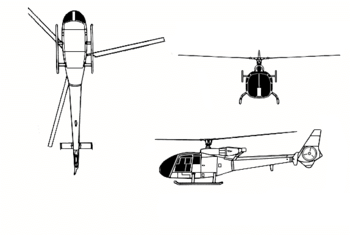

The Aérospatiale Gazelle is a French five-seat helicopter, commonly used for light transport, scouting and light attack duties. It is powered by a single turbine engine and was the first helicopter to feature a fenestron tail instead of a conventional tail rotor. It was designed by Sud Aviation, later Aérospatiale, and manufactured in France and the United Kingdom through a joint production agreement with Westland Aircraft. Further manufacturing under license was performed by SOKO in Yugoslavia and the Arab British Helicopter Company (ABHCO) in Egypt.

Since being introduced to service in 1973, the Gazelle has been procured and operated by a number of export customers. It has also participated in numerous conflicts around the world, including by Syria during the 1982 Lebanon War, by Rwanda during the Rwandan Civil War in the 1990s, and by numerous participants on both sides of the 1991 Gulf War. In French service, the Gazelle has been supplemented as an attack helicopter by the larger Eurocopter Tiger, but remains in use primarily as a scout helicopter.

Development

The Gazelle originated in a French Army requirement for a lightweight observation helicopter intended to replace the Aérospatiale Alouette III; early on in the aircraft's development, the decision was taken to enlarge the helicopter to enable greater versatility and make it more attractive for the export market.[2] In 1966, Sud Aviation began working on a light observation helicopter to replace its Alouette II with seating for five people.[3] The first prototype SA 340 flew for the first time on 7 April 1967, it initially flew with a conventional tail rotor taken from the Alouette II. The tail was replaced in early 1968 with the distinctive fenestron tail on the second prototype.[3][4] Four SA 341 prototypes were flown, including one for British firm Westland Helicopters. On 6 August 1971, the first production Gazelle conducted its first flight.[4] On 13 May 1967, a Gazelle demonstrated its speed capabilities when two separate world speed records were broken on a closed course, achieving speeds of 307 km/h over 3 kilometres and 292 km/h over 100 kilometres.[5]

Early on, the Gazelle had attracted British interest, which would culminate in the issuing of a major joint development and production work share agreement between Aerospatiale and Westland. The deal, signed in February 1967, allowed the production in Britain of 292 Gazelles and 48 Aérospatiale Pumas ordered by the British armed forces; in return Aérospatiale was given a work share in the manufacturing programme for the 40 Westland Lynx naval helicopters for the French Navy. Additionally, Westland would have a 65% work share in the manufacturing, and be a joint partner to Aérospatiale on further refinements and upgrades to the Gazelle. Westland would produce a total of 262 Gazelles of various models, mainly for various branches of the British armed forces, Gazelles for the civil market were also produced.[6][7]

In service with the French Army Light Aviation (ALAT), the Gazelle is used primarily as an anti-tank gunship (SA 342M) armed with Euromissile HOT missiles. A light support version (SA 341F) equipped with a 20 mm cannon is used as well as anti-air variants carrying the Mistral air-to-air missile (Gazelle Celtic based on the SA 341F, Gazelle Mistral based on the SA 342M). The latest anti-tank and reconnaissance versions carry the Viviane thermal imagery system and so are called Gazelle Viviane.[8] The Gazelle is being replaced in frontline duties by the Eurocopter Tiger, but will continue to be used for light transport and liaison roles.

It also served with all branches of the British armed forces—the Royal Air Force, Royal Navy (including in support of the Royal Marines) and the British Army in a variety of roles. Four versions of the Gazelle were used by the British forces. The SA 341D was designated Gazelle HT.3 in RAF service, equipped as a helicopter pilot trainer (hence HT). The SA 341E was used by the RAF for communications duties and VIP transport as the Gazelle HCC.4. The SA 341C was purchased as the Gazelle HT.2 pilot trainer for the Royal Navy; training variants have been replaced by the Squirrel HT1.[9] The SA 341B was equipped to a specification for the Army Air Corps as the Gazelle AH.1 (from Army Helicopter Mark 1).

The Gazelle proved to be a commercial success, which led Aerospatiale to quickly develop and introduce the SA 341 Gazelle series, which was equipped with considerably more powerful engines. Licensed production of the type did not just take place in the UK, domestic manufacturing was also conducted by Egyptian firm ABHCO. Yugoslavian production by SOKO reportedly produced a total of 132 Gazelles.[6] As the Gazelle became progressively older, newer combat helicopters were brought into service in the anti-tank role; thus those aircraft previously configured as attack helicopters were often repurposed for other, secondary support duties, such as an Air Observation Post (AOP) for directing artillery fire, airborne forward air controller (ABFAC) to direct ground-attack aircraft, casualty evacuation, liaison, and communications relay missions.[10]

Design

The Aérospatiale Gazelle is an agile, fast-moving helicopter, originally developed as a replacement to Aérospatiale's Alouette helicopter family. While some aspects of the Gazelle, such as its purpose and layout resembles the preceding Alouette, the Gazelle featured several important innovations. It was the first helicopter to carry a fenestron or fantail; this is a shrowded multi-blade anti-torque device housed internally upon the vertical surface of the Gazelle's tail, which replaces a conventional tail rotor entirely.[4] The fenestron, while requiring a small increase in power at slow speeds, has advantages such as being considerably less vulnerable and low power requirements during cruise speeds, and has been described as "far more suitable for high-speed flight".[11][12] The fenestron is likely to have been one of the key advances that allowed the Gazelle to become the world's fastest helicopter in its class.[1]

The main rotor system had originally based upon the rigid rotor technology developed by Messerschmitt-Bölkow-Blohm for the MBB Bo 105; however, due to control problems experienced while at high speeds upon prototype aircraft, the rigid rotor was replaced with a semi-articulated one on production aircraft. The difficulties experienced with the early design of the main rotor was one of the factors contributing to the lengthy development time of the Gazelle.[13] The individual rotor blades were crafted out of composite materials, primarily composed of fiberglass, and had been designed for an extremely long operational lifespan; composite rotor blades would become a common feature of later helicopters.[11][14] The main rotor maintains a constant speed in normal flight, and is described as having a "wide range of tolerance" for autorotation.[15]

The Gazelle is capable of transporting up to five passengers and up to 1,320 pounds of cargo on the underside cargo hook, or alternatively up to 1,100 pounds of freight in 80 cubic feet of internal space in the rear of the cabin. Armed variants would carry up to four HOT (Haut subsonique Optiquement Téléguidé Tiré d'un Tube) wire-guided anti-tank missiles, or a forward firing 20mm cannon mounted to the fuselage sides with its ammunition supply placed in the cabin.[16] Various optional equipment can be installed upon the Gazelle, such as fittings for engine noise suppression, 53 gallon ferry tanks, a rescue winch capable of lifting up to 390 pounds, emergency flotation gear, particle filter, high landing skids, cabin heater, adjustable landing lights, and engine anti-icing systems.[17] While the Gazelle had been developed under a military-orientated design programme, following the type's entry to service increasing attention to the commercial market was paid as well.[18] The type was marketed to civil customers; notably, civilian operator Vought Helicopters at one point had a fleet of at least 70 Gazelles.[6][19] Civil-orientated Gazelles often included an external baggage access door mounted beneath the main cabin.[20]

The Gazelle was the first helicopter to be adapted for single-pilot operations under instrument flight rules. An advanced duplex autopilot system was developed by Honeywell in order to allow the pilot to not be overworked during solo flights; the Gazelle was chosen as the platform to develop this capability as it was one of the faster and more stable helicopters in service at that point and had a reputation for being easy to fly.[21] The docile flying abilities of the Gazelle are such that it has been reported as being capable of comfortably flying without its main hydraulic system operation at speeds of up to 100 knots.[22] The flight controls are highly responsive; unusually, the Gazelle lacks a throttle or a trimming system. Hydraulic servo boosters are present on all flight control circuits to mitigate control difficulties in the event of equipment failure.[19][22]

The Gazelle was designed to be easy to maintain, all bearings were life-rated without need for continuous application of lubrication and most fluid reservoirs to be rapidly inspected.[22] The emphasis in the design stage of achieving minimal maintenance requirements contributed towards the helicopter's low running costs; many of the components were designed to have a service life in excess of 700 flying hours, and in some cases 1,200 flight hours, before requiring replacement.[23] Due to the performance of many of the Gazelle's subsystems, features pioneered upon the Gazelle such as the fenestron would appear upon later Aerospatiale designs.[13][24]

As the Gazelle continued to serve into the 21st century, several major modernization and upgrade programs were undertaken, commonly adding new avionics to increase the aircraft's capabilities. Aerotec group offered an overhaul package to existing operators, which comprised upgraded ballistic protection, night vision goggles, new munitions including rockets and machine guns, and 3D navigational displays; as of 2013, Egypt is said to be interested in upgrading their domestically-built Gazelles.[25] QinetiQ developed a Direct Voice Input (DVI) system for the Gazelle, it has been installed and is operating on those aircraft used by the British Army Air Corps; the DVI system enables voice control over many aspects of the aircraft, lowering the demands placed upon the crew.[26] In September 2011, QinetiQ and Northrop Grumman proposed outfitting former British Gazelles with autonomous flight management systems derived from the Northrop Grumman MQ-8 Fire Scout, converting them into unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV)s to meet a Royal Navy requirement for an unmanned maritime aerial platform.[27]

Operational history

China

During the 1980s, China acquired eight SA 342L combat helicopters; these were the first dedicated attack helicopters to be operated by the People's Liberation Army. The purchase of further aircraft, including licensed production of the aircraft in China, had been under consideration, but this initiative was apparently abandoned following the end of the Cold War. The small fleet was used to develop anti-armour warfare tactics, Gazelles have also been frequently used to simulate hostile forces during military training exercises.[28]

France

The French Army have deployed the Gazelle overseas in many large-scale operations, often in support of international military intervention efforts; including in Chad (in the 1980s),[29] the former Yugoslavia (1990s), Djibouti (1991–1992),[30] Somalia (1993), Cote d'Ivoire (2002–present) and Afghanistan (2002–present). In 1990-1991, upwards of 50 French Gazelles were deployed as part of France's contribution to coalition forces during the First Gulf War;[31] during the subsequent military action, known as Operation Desert Storm, HOT-carrying Gazelles were employed by multiple nations, including Kuwait's air force, against Iraqi military forces occupying neighbouring Kuwait.[32] During the coalition's offensive into Kuwait, French Gazelles adopted a tactic of continuous waves strafing enemy tanks, vehicles, and bunkers during high speed passes.[33]

Gazelles have often been dispatched to support and protect UN international missions, such as the 1992 intervention in the Bosnian War.[34] In addition to performing land-based operations, French Gazelles have also been frequently deployed from French naval vessels. In April 2008, witnesses reported up to six French Gazelles reportedly firing rockets upon Somali pirates during a major counter-piracy operation.[35] During the 2011 military intervention in Libya, multiple Gazelles were operated from the French Navy's amphibious assault ship Tonnerre; strikes were launched into Libya against pro-Gadhafi military forces.[36]

Military interventions in African nations, particularly former French colonies, have often been supported by Gazelles in both reconnaissance and attack roles; nations involved in previous engagements include Chad, Djibouti, Somalia, and the Cote d'Ivoire. In April 2011, as part of a UN-mandated campaign in Cote d'Ivoire, four Gazelle attack helicopters, accompanied by two Mil Mi-24 gunships, opened fire upon the compound of rebel president Gbagbo to neutralise heavy weaponry, which led to his surrender.[37] In January 2013, Gazelles were used as gunships in the Opération Serval in Mali, performing raids upon insurgent forces fighting government forces in the north of the country.[38][39]

Iraq

During the Iran–Iraq War fought throughout most of the 1980s, a significant amount of French-built military equipment was purchased by Iraq, including a fleet of 40, HOT-armed Gazelles.[40] Iraq reportedly received roughly 100 Gazelle helicopters.[41] The Gazelle was commonly used in conjunction with Russian-built Mil Mi-24 Hind gunships, and were frequently used in counterattacks against Iranian forces.[42] By 2000, following significant equipment losses resulting from the 1991 Gulf War, Iraq reportedly had only 20 Gazelles left in its inventory.[43]

In 2003, US intelligence officials alleged that a French firm had continued to sell to Iraq spare components for the Gazelle and other, French-built aircraft, via a third-party trading company despite an embargo being in place.[44] Eurocopter, Aerospatiale's successor company, had denied playing any role, stating in 2008 that "no parts have been delivered to Iraq".[45] In April 2009, Iraq, as part of a larger military procurement initiative, bought six Gazelles from France for training purposes.[46]

Syria

Syrian Gazelles were used extensively during the 1982 Lebanon War. In the face of a major Israeli ground advance, repetitive harassment attacks were launched by the Gazelles, which were able to slow their advance.[47] According to author Roger Spiller, panic and a sense of vulnerability quickly spread amongst Israeli tank crews following the first of these Gazelle strikes on 8 June 1982; the range of the Gazelle's HOT missiles being a key factor in its effectiveness.[48] The effectiveness of the Syrian helicopter raids was reduced throughout the month of June as Syrian air defenses were progressively eroded and the Israeli Air Force took aerial supremacy over Eastern Lebanon, thus making operations by attack helicopters increasingly vulnerable. However, Gazelle strikes continued to be successfully performed up to the issuing of a ceasefire.[49]

The 1982 war served to highlight the importance and role of attack helicopters in future conflicts due to their performance on both sides of the conflict.[50] Following the end of the war, the Syrian Army would claim that significant damage had been delivered against Israeli forces, such as the destruction of 30 tanks and 50 other vehicles, against the loss of five helicopters.[51] Israel would claim a loss of seven tanks to the Gazelle strikes and the downing of 12 Syrian Gazelles.[49] Author Kenneth Michael Pollack described the role of Syria's Gazelle helicopters as being "psychologically effective against the Israelis but did little actual damage. Although they employed good Western-style 'pop-up' tactics, the Gazelles were not able to manage more than a few armor kills during the war".[52]

Following the end of the war, Syria dramatically increased the size of its attack helicopter fleet from 16 to 50 Gazelles, complimented by a further 50 heavier Mil Mi-24 gunships.[50]

Kuwait

During the 1991 Gulf War, roughly 15 Gazelles were able to retreat into neighbouring Saudi Arabia, along with other elements of Kuwait's armed forces, during the invasion of the nation by Iraq.[53] During the subsequent coalition offensive to dislodge Iraqi forces from Kuwait, several of the escaped, Kuwaiti Gazelles launched attack missions into occupied Kuwait to destroy Iraqi tanks and other, military targets.[54]

Ecuador

The Gazelle was used by the Ecuadoran Army during the 1995 Cenepa war between Ecuador and neighboring Peru, performing missions such close air support of ground forces and escorting other helicopters.[55] In 2008, a minor diplomatic spat broke out between Colombia and Ecuador following a reportedly accidental incursion into Columbian airspace by an Ecuadoran Gazelle.[56]

United Kingdom

In 1973, 142 aircraft were on order by the UK, out of a then-intended fleet of 250.[57] No. 660 Squadron AAC, based in Salamanca Barracks, Germany, was the first British Army unit to be equipped with Gazelles, entering operational service on 6 July 1974. The Gazelles, replacements for the Sioux, were assigned the roles of reconnaissance, troop deployment, direction of artillery fire, casualty evacuation and anti-tank operations.[58][59] In August 1974, 30 were based at CFS Tern Hill for RAF helicopter training.[60]

The Royal Navy's Gazelles entered service in December 1974 with 705 Naval Air Squadron, Culdrose, to provide all-through flying training in preparation for the Lynx's service entry. A total of 23 Gazelles were ordered for Culdrose.[61] Army-owned AH.1s also entered service with 3 Commando Brigade Air Squadron (3 CBAS) of the Royal Marines and later, the Commando Helicopter Force (CHF) of the Fleet Air Arm, where they operated as utility and reconnaissance helicopters in support of the Royal Marines.[62] The 12 Gazelles for 3 CBAS had entered service in 1975,[63] by which time, there were 310 Gazelles on order for the British military.[64]

Gazelles that had replaced the Siouxs in RAF Sek Kong towards the end of 1974 had been found unsuitable for Hong Kong and, by the end of 1975, had been returned to the UK.[65] During its Cold War service period, the Army Gazelles flew over 660,000 hours and had over 1,000 modifications made to the aircraft. From the early 1980s, Army-operated Gazelles were fitted with the Gazelle Obvervation Aid, a gyro-stabilised sight to match their target finding capability with that of the Lynx.[65][66] The type also had a limited, special operations aviation role with 8 Flight Army Air Corps

The type was also frequently used to perform airborne patrols in Northern Ireland. On 17 February 1978, a British Army Gazelle crashed near Jonesborough, County Armagh, after coming under fire from the Provisional IRA during a ground skirmish.[67]

During the Falklands War, the Gazelle played a valuable role operating from the flight decks of Royal Navy ships. Under a rapidly-performed crash programme specifically for the Falklands conflict, Gazelles were fitted with 68mm SNEB rocket pods and various other optional equipment such as armour plating, flotation gear and folding blade mechanisms.[68] Two Royal Marines Gazelles were shot down on the first day of the landings at San Carlos Water.[69] In a high-profile incident of friendly fire on 6 June 1982, an Army Air Corps Gazelle was mistaken for a low-flying Argentine C-130 Hercules and was shot down by HMS Cardiff, a British Type 42 Destroyer.[70][71]

.jpg)

The Gazelle also operated in reconnaissance and liaison roles during the War in Afghanistan. In 2007, it was reported that, while many British helicopters had struggled with the conditions of the Afghan and Iraqi theatres, the Gazelle was the "best performing model" with roughly 80% being available for planned operations.[72]

Various branches of the British military have operated Gazelles in other theatres, such as during the 1991 Gulf War against Iraq and in the 1999 intervention in Kosovo.[73] While the type was originally intended to be retired in 2012, the Gazelle will continue to be operated in a policing capacity in Northern Ireland until 2018, at which point the Police Service of Northern Ireland is to have the assets to fill this role itself.[74]

Yugoslavia

On 27 June 1991, during Ten Day War in Slovenia, a Yugoslav Air Force Gazelle helicopter was shot down by a man-portable Strela 2 missile over Ljubljana, the first aircraft to be lost during the breakup of Yugoslavia.[75] Next day 28 June 1991 two Slovenian members of Yugoslav army (pilot Jože Kalan, the technician Bogo Šuštar) escaped from federal army and joined the Territorial defence with helicopter (serial number JLV 12660). The helicopter received a new code, T-001 Velenje, the Slovenian emblem and was kept hidden in private barn till the end of conflict in Slovenia.Story in Slovene language The Gazelles would see conflict in the subsequent Yugoslav Wars and the Kosovo War; as Yugoslavia dissolved, multiple successor states would inherit the SOKO-built Gazelles and continue to operate them, such as the Army of Bosnia and the Serbian Air Force.[76]

Lebanon

During the 1980s, Lebanon acquired a small fleet of eight armed SA 342K Gazelles; an additional nine SA 342 Gazelles formerly of the United Arab Emirates Air Force were delivered in 2007.[77] Due to budget limitations, the majority of the Gazelles, which are operated by the Lebanese Air Force, have often been kept in storage outside of times of conflict.[77] The Gazelles saw combat against the Al Qaeda-inspired Fatah al-Islam militants during the 2007 Lebanon conflict.[78] Rocket-armed Gazelles were used to strike insurgent bunkers during the brief conflict.[77] In 2010, a French government official stated that France had offered to provide up to 100 HOT missiles to Lebanon for the Gazelle helicopters.[79] According to reports, France may also provide additional Gazelles to Lebanon.[77]

Morocco

In January 1981, France and Morocco entered into a $4 billion military procurement deal in which, amongst other vehicles and equipment, 24 Gazelle helicopters were to be delivered to Morocco.[80] The Royal Moroccan Army operated these Gazelles, which were equipped with a mix of anti-tank missiles and other ground attack munitions, and made frequent use of the aircraft during battles with Polisario insurgents in the western Sahara region.[81] The reconnaissance capabilities of the Gazelle were instrumental in finding and launching attacks upon insurgent camps due to their mobility.[82]

Rwanda

In 1990, following appeals from Rwandan President Juvénal Habyarimana for French support in interethnic conflict against the Tutsi Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), nine armed Gazelles were exported to Rwanda in 1992. The Gazelles would see considerable use in the conflict that became known as the Rwandan Civil War, capable of strafing enemy positions as well as performing reconnaissance patrols of Northern Rwanda; in October 1992, a single Gazelle destroyed a column of ten RPF units.[83] According to author Andrew Wallis, the Gazelle gunships helped to stop significant RPF advances and led to a major change in RPF tactics towards guerrilla warfare.[84] In 1994, French forces dispatched as a part of Opération Turquoise, a United Nations-mandated intervention in the conflict, also operated a number of Gazelles in the theatre.[85]

Egypt

As part of a major international initiative formalised in 1975 to build up Arab military industries, Egypt commenced widescale efforts to replace arms imports with domestic production to provide military equipment to the rest of the Middle East, other Arab partner nations included Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar.[86] Both France and Britain would form large agreements with Egypt; in March 1978, the Arab British Helicopter Company (ABHCO) was formally established in a $595 million deal with Westland Helicopters, initially for the purpose of domestically assembly of British Westland Lynx helicopters.[87] An initial order for 42 Gazelles was placed in mid-1975.[88] In the 1980s, ABHCO performed the assembly of a significant number of Gazelles; the British Arab Engine Company also produced engines for Egyptian-build Gazelles.[89]

According to reports in 1986, large quantities of military equipment had been illicitly channeled from Egypt to South Africa via Israel; one such arms shipment is alleged to have included 50 Gazelle helicopters purchased from Egypt by Adnan Khashoggi, an international arms dealer, where they were shipped directly to Israel and then to South Africa, where they were likely used by the South African armed forces.[90]

Variants

- SA 340

- First prototype, first flown on 7 April 1967 with a conventional Alouette type tail rotor.

- SA 341

- Four pre-production machines. First flown on 2 August 1968. The third was equipped to British Army requirements and assembled in France as the prototype Gazelle AH.1. This was first flown on 28 April 1970.

- SA 341.1001

- First French production machine. Initial test flight 6 August 1971. Featured a longer cabin, an enlarged tail unit and an uprated Turbomeca Astazou IIIA engine.

- SA 341B (Westland Gazelle AH.1)

- Version built for the British Army; Featured the Astazou IIIN2 engine, capable of operating a nightsun searchlight, later fitted with radio location via ARC 340 radio and modified to fire 68mm SNEB rockets. First Westland-assembled version flown on 31 January 1972, this variant entered service on 6 July 1974. A total of 158 were produced. A small number were also operated by the Fleet Air Arm in support of the Royal Marines.

- SA 341C (Westland Gazelle HT.2)

- Training helicopter version built for British Fleet Air Arm; Features included the Astazou IIIN2 engine, a stability augmentation system and a hoist. First flown on 6 July 1972, this variant entered operational service on 10 December 1974. A total of 30 were produced.

- SA 341D (Westland Gazelle HT.3)

- Training helicopter version built for British Royal Air Force; Featuring the same engine and stability system as the 341C, this version was first delivered on 16 July 1973. A total of 14 were produced.

- SA 341E (Westland Gazelle HCC.4)

- Communications helicopter version built for British Royal Air Force; Only one example of this variant was produced.

- SA 341F

- Version built for the French Army; Featuring the Astazou IIIC engine, 166 of these were produced. Some of these were fitted with an M621 20-mm cannon.

- SA 341G

- Civil variant, powered by an Astazou IIIA engine. Officially certificated on 7 June 1972; subsequently became first helicopter to obtain single-pilot IFR Cat 1 approval in the US. Also developed into "Stretched Gazelle" with the cabin modified to allow an additional 8 inches (20cm) legroom for the rear passengers.[91]

- SA 341H

- Military export variant, powered by an Astazou IIIB engine. Built under licence agreement signed on 1 October 1971 by SOKO in Yugoslavia.

- SOKO HO-42

- Yugoslav-built version of SA 341H.

- SOKO HI-42 Hera

- Yugoslav-built scout version of SA 341H.

- SOKO HN-42M Gama

- Yugoslav-built attack version of SA 341H.

- SOKO HN-45M Gama 2

- Yugoslav-built attack version of SA 342L.

- SOKO HS-42

- Yugoslav-built medic version of SA 341H.

- SA 342J

- Civil version of SA 342L. This was fitted with the more powerful 649 kW (870 shp) Astazou XIV engine and an improved Fenestron tail rotor. With an increased take-off weight, this variant was approved on 24 April 1976, and entered service in 1977.

- SA 342K

- Military export version for "hot and dry areas". Fitted with the more powerful 649-kW (870-shp) Astazou XIV engine and shrouds over the air intakes. First flown on 11 May 1973; initially sold to Kuwait.

- SA 342L

- Military companion of the SA 342J. fitted with the Astazou XIV engine. Adaptable for many armaments and equipment, including six Euromissile HOT anti-tank missiles.

- SA 342M

- French Army anti-tank version fitted with the Astazou XIV engine. Armed with four Euromissile HOT missiles and a SFIM APX M397 stabilised sight.

- SA 342M1

- SA 342M retrofitted with three Ecureuil main blades to improve performance.

- SA 349

- Experimental aircraft, outfitted with stub wings.[5]

Operators

Current

Former

Specifications (SA 341)

|

| |

|

|

Data from Airplane Magazine Vol 1 Issue 6

General characteristics

- Crew: 2

- Capacity: 3 Passengers

- Length: 11.97 m (39 ft 0 in)

- Main rotor diameter: 10.5 m (34 ft 6 in)

- Height: 3.15 m (10 ft 3 in)

- Main rotor area: 86.5 m2 (931 ft2)

- Empty weight: 908 kg (2,002 lb)

- Gross weight: 1,800 kg (3,970 lb)

- Powerplant: 1 × Turbomeca Astazou IIIA turboshaft, 440 kW (590 hp)

Performance

- Maximum speed: 310 km/h (193 mph)

- Cruising speed: 264 km/h (164 mph)

- Range: 670 km (416 miles)

- Service ceiling: 5,000 m (16,405 ft)

- Rate of climb: 9 m/s (1,770 ft/min)

Popular culture

See also

- Related development

- Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Related lists

- List of helicopters

- List of active United Kingdom military aircraft

- List of aircraft of the Army Air Corps

References

Citations

- 1 2 Fricker 1973, p. 72.

- ↑ Air International December 1977, pp. 277–278.

- 1 2 Giorgio 1984, p. 98.

- 1 2 3 McGowen 2005, p. 124.

- 1 2 "1967: SA340 "Gazelle." Eurocopter, Retrieved: 25 June 2013.

- 1 2 3 McGowen 2005, p. 125.

- ↑ Field 1973, p. 585.

- ↑ "Gazelle viviane sa 342 M1." defense.gouv.fr, Retrieved: 24 June 2013.

- ↑ "Squirrel HT1." Royal Air Force, Retrieved: 25 June 2013.

- ↑ Crawford 2003, p. 35.

- 1 2 Fricker 1973, p. 73.

- ↑ Mouille, Rene´. "The “Fenestron,“ Shrouded Tail Rotor of the SA. 341 Gazelle." Journal of the American Helicopter Society, Vol. 15, No. 4. October 1970, pp. 31-37.

- 1 2 Field 1973, p. 194.

- ↑ Field 1973, p. 587.

- ↑ Fricker 1973, p. 76.

- ↑ Tucker 2010, p. 49.

- ↑ Fricker 1973, pp. 75-76.

- ↑ Field 1973, p. 193.

- 1 2 Field 1973, p. 589.

- ↑ Field 1973, p. 588.

- ↑ McClellan 1989, pp. 30-31.

- 1 2 3 Fricker 1973, p. 75.

- ↑ Field 1973, pp. 193-194.

- ↑ Vuillet, A. and F. Morelli. "New Aerodynamic Design of the Fenestron for Improved Performance." Aérospatiale, June 1987.

- ↑ "Aerotec homes in on new customers for Gazelle upgrade." Flight International, 19 June 2013.

- ↑ "QinetiQ speech recognition technology allows voice control of aircraft systems". QinetiQ, Retrieved: 14 June 2013.

- ↑ Hoyle, Craig. "DSEi: Qinetiq, Northrop offer UK unmanned Gazelle conversion." Flight International, 15 September 2011.

- ↑ Crawford 2003, p. 13.

- ↑ "French Jets Aid in Route, Says West." Philadelphia Inquirer, 4 September 1983.

- ↑ "France boosts military presence in Djibouti." AFP, 22 January 1999.

- ↑ Donald and Chant 2001, pp. 37-38.

- ↑ Donald and Chant 2001, p. 43.

- ↑ Lowry 2008, p. 104.

- ↑ Rosenthal, Andrew. "Bush Pledges Aid, Not Troops, To Help Bosnian Government." Star News, 10 July 1992.

- ↑ "French helicopters fire at Somali pirates: witnesses." Reuters, 11 April 2008.

- ↑ "Libye : début des opérations aériennes françaises" (in French). French Ministry of Defense. 19 March 2011.

- ↑ Laing, Aislinn (10 April 2011). "Ivory Coast: UN and French helicopter gunships attack Laurent Gbagbo residence". The Telegraph.

- ↑ "Mali: Hollande réunit son conseil de Défense à l'Elysée". Libération (in French). 12 January 2013. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ↑ "Mali : l'opération militaire française "durera le temps nécessaire"". Le Monde. 12 January 2013.

- ↑ Ashton and Gibson 2012, pp. 217-219.

- ↑ Tucker 2010, p. 582.

- ↑ Tucker 2010, p. 50.

- ↑ "World Air Forces Directory" (pdf), Flight International, 28 November – 4 December 2000: 70

- ↑ "Iraq is resupplying its air force with French parts, officials say". Deseret News, 7 March 2003.

- ↑ Apter, Jeff. "Eurocopter denies illegal sales to Iraq ." Aviation News International, 23 January 2008.

- ↑ "Iraq signs weapons deal with US & Europe." Arabian Aerospace, 6 April 2009.

- ↑ Pollack 2002, pp. 530, 538.

- ↑ Spiller 1992, pp. 37-39.

- 1 2 Spiller 1992, p. 39.

- 1 2 Spiller 1992, p. 40.

- ↑ Cooper, Tom and Yaser al-Abed. "Syrian Tank-Hunters in Lebanon, 1982". ACIG, 26 September 2003.

- ↑ Pollack 2002, p. 544.

- ↑ "Kuwaiti pilots hit homeland." The Union Democrat, 6 February 1991.

- ↑ Lowry 2008, p. 65.

- ↑ Gazelle En la Aviación del Ejercito Ecuatoriano (in Spanish). fuerzaaerea.net "Gazelle In the Ecuadorian Army Aviation" (English translation).

- ↑ "'Ecuador incursion' into Colombia." BBC News, 1 April 2008.

- ↑ "Helicopters" (pdf). Flight International: 861. 22 Nov 1973. Retrieved 10 Nov 2014.

- ↑ "Aerospatiale/Kaman ASH agreement". Flight International. 1 August 1974. Retrieved 10 Nov 2014.

- ↑ QRA Magazin (2013). "Army Air Corps in Germany". qra-magazin.de. Retrieved 10 Nov 2014.

- ↑ "United Kingdom" (pdf). Flight International: 188. 15 August 1974. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- ↑ "Defence". Flight Global. 16 Jan 1975. Retrieved 10 Nov 2014.

- ↑ 847 squadron, Helicopter History Site, 2014, retrieved 11 Nov 2014

- ↑ UK Mod (2014). "847 NAS Affiliations". UK MoD. Retrieved 10 Nov 2014.

- ↑ Barry Wheeler (17 Jul 1975). "Word's military helicopters". Flight Global. Retrieved 10 Nov 2014.

- 1 2 Kneen, J M.; Sutton, D J (1997). Craftsmen of the Army: The Story of the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers Vol II 1969-1992. Pen and Sword. ISBN 9781473813403. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ↑ "Ferranti sight for Gazelle" (PDF). Flight Global. 9 May 1981. Retrieved 11 Nov 2014.

- ↑ "British Army to publish Gazelle crash findings." Flight International, 18 March 1978.

- ↑ Battle for the Falklands (3): Air Forces. Osprey Publishing, 1982. ISBN 0-85045-493-X. p. 14.

- ↑ Freedman, Lawrence (2005). The Official History of the Falklands Campaign: War and diplomacy, Vol 2. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 0-203-50785-1.

- ↑ Masakowski, Yvonne; Cook, Malcolm; Noyes, Jan (2007). Decision-making in Complex Environments. Ashgate Publishing. p. 197. ISBN 0-7546-4950-4. Retrieved 11 March 2008.

- ↑ Bolia, Robert S. "The Falklands War: The Bluff Cove Disaster" (PDF). Military Review (November–December 2004): 66–72. Retrieved 26 April 2008.

- ↑ Watts, Robert. "Half of Army gunships are grounded." The Telegraph, 11 November 2007.

- ↑ Ripley, Tim (2011). British Army Aviation in Action. Pen & Sword Books. pp. 49, 69. ISBN 978-1-84884-670-8. Retrieved 11 Nov 2014.

- ↑ Jennings, Gareth. "British Army Gazelles move closer to the Ulster retirement." IHS Jane's Defence Weekly, 17 March 2013.

- ↑ Ripley 2001, p. 7.

- ↑ Ripley 2001, p. 81.

- 1 2 3 4 Lake, Jon. "Small force with a wealth of history." Arabian Aerospace, 31 October 2010.

- ↑ "Lebanese target suspected militants inside refugee camp". CNN, 16 June 2007.

- ↑ "France gives Lebanon anti-tank missiles". The Associated Press, 17 December 2010.

- ↑ Keucher 1989, p. 66.

- ↑ Zoubir 1999, pp. 212-213.

- ↑ Zoubir 1999, p. 214.

- ↑ Wallis 2006, pp. 30-31.

- ↑ Wallis 2006, pp. 28-29.

- ↑ Wallis 2006, pp. 129-131.

- ↑ Feiler 2003, p. 57.

- ↑ Feiler 2003, p. 59.

- ↑ Feiler 2003, p. 20.

- ↑ Feiler 2003, p. 60.

- ↑ Hunter 1987, p. 42.

- ↑ Taylor 1982, p. 55.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 "World Air Forces 2013" (PDF). Flightglobal Insight. 2013. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ↑ Serbian Police Aircraft

- ↑ "World Air Forces 1993 pg. 48". flightglobal.com. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ↑ "World Air Forces 1993", Flight International (flightglobal.com), 24–30 November 1993: 60, retrieved 5 April 2013

- ↑ "Irish Military retired Aircraft". irishmilitaryonline.com. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ↑ "Air Forces of the World 1997", Flight International (flightglobal.com), 10–16 September 1997: 71, retrieved 5 April 2013

- ↑ "World Air Forces 2004pg. 46". flightglobal.com. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ↑ "RAF SA341D Gazelle HT.3". Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ↑ "Fleet Air Arm SA341C Gazelle HT.2". Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ↑ "World Air Forces 1987 pg. 67". flightglobal.com. Retrieved 2013-10-03.

Bibliography

- Cocault Gerald. "A l'assaut du desert". French army (ALAT) in the first Gulf war (1990) ISBN 9782810623297

- Ashton, Nigel and Bryan Gibson. The Iran-Iraq War: New International Perspectives. Taylor & Francis, 2013. ISBN 1-13511-536-2.

- Chant, Chris (2013). Air War in the Falklands 1982. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-47280-051-6.

- Crawford, Stephen. Twenty First Century Military Helicopters: Today's Fighting Gunships. Zenith Imprint, 2003. ISBN 0-76031-504-3.

- Eden, Paul, ed. (2004). The Encyclopedia of Modern Military Aircraft. London, UK: Amber Books. ISBN 1-904687-84-9.

- Feiler, Gil. Economic Relations Between Egypt and the Gulf Oil States, 1967-2000: Petro Wealth and Patterns of Influence. Sussex Academic Press, 2003. ISBN 1-90390-040-9.

- Gunston, Bill; Lake, Jon; Mason, Francis K. (1990). "A-Z of Aircraft: Aerospatiale Gazelle". Airplane Magazine. Vol. 1 no. 6. p. 165.

- Field, Hugh. "Anglo-French rotary collaboration goes civil." Flight International, 8 February 1973. pp. 173–174.

- Field, Hugh (12 April 1973). "Nimble Gazelle". Flight International. pp. 585–589

- "Franco–British Antelope: The First Ten Years in the Life of the Aerospatiale/Westland Gazelle". Air International. Vol. 13 no. 6. December 1977. pp. 277–283, 300.

- Fricker, John (February 1973). "The Gazelle: Looking at American Pastures". Flying Magazine. Vol. 92 no. 2. pp. 72–76.

- Giorgio, Apostolo (1984). "SA.341 Gazelle". The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Helicopters. New York: Bonanza Books. ISBN 978-0-517-43935-7.

- Hoyle, Craig (13–19 December 2011). "World Air Force Directory". Flight International. Vol. 180 no. 5321. pp. 26–52. ISSN 0015-3710.

- Hunter, Jane. Israeli Foreign Policy: South Africa and Central America. South End Press, 1987. ISBN 0-89608-285-7.

- Keucher, Ernest R. "Military assistance and foreign policy". Air Force Institute of Technology, 1989. ISBN 0-91617-101-9.

- Lowry, Richard. The Gulf War Chronicles: A Military History of the First War with Iraq. iUniverse, 2008. ISBN 0-59560-075-1.

- McClellan, J. Mac (December 1989). "Churning up the Soup". Flying Magazine. Vol. 116 no. 12. pp. 30–31. ISSN 0015-4806.

- McGowen, Stanley S. Helicopters: An Illustrated History Of Their Impact. ABC-CLIO, 2005. ISBN 1-85109-468-7.

- "Mid '70s Roundup". Flying Magazine. Vol. 98 no. 2. February 1976. p. 94.

- Pollack, Kenneth Michael. Arabs at War: Military Effectiveness, 1948-1991. University of Nebraska Press, 2002. ISBN 0-80320-686-0.

- Ripley, Tim. Conflict in the Balkans: 1991-2000. Osprey Publishing, 2001. ISBN 1-84176-290-3.

- Spiller, Roger J. Combined arms in battle since 1939. U.S. Army Command and General Staff College Press, 1992. ISBN 1-42891-537-0.

- Taylor, John W. R. (1982). Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1982–83. London: Jane's Yearbooks. ISBN 0-7106-0748-2.

- Tucker, Spencer S. The Encyclopedia of Middle East Wars: The United States in the Persian Gulf, Afghanistan, and Iraq Conflicts. ABC-CLIO, 2010. ISBN 1-85109-948-4.

- Wallis, Andrew. Silent Accomplice: The Untold Story of France's Role in the Rwandan Genocide. I.B.Tauris, 2006. ISBN 1-84511-247-4.

- Zoubir, Yahia H. "North Africa in Transition: State, Society, and Economic Transformation in the 1990s". University Press of Florida, 1999. ISBN 0-81301-655-X.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aérospatiale Gazelle. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Westland Gazelle. |

- Images of Aérospatiale Gazelle on airliners.net

- Restoration of XX411 at aeroventure.org.uk

- "British and French attack helicopters build strong partnership." - Ministry of Defence, May 2013.

| ||||||||||||||||||||

|