Tyrsenian languages

| Tyrsenian | |

|---|---|

| Tyrrhenian | |

| Geographic distribution: | Southern Europe |

| Linguistic classification: | One of the world's primary language families |

| Subdivisions: | |

| Glottolog: | etru1243[1] |

|

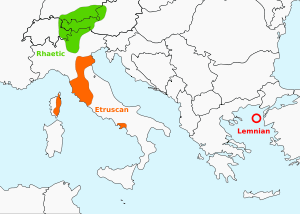

Approximate area of Tyrsenian languages | |

Tyrsenian (also Tyrrhenian), named after the Tyrrhenians (Ancient Greek (Ionic): Τυρσηνοί Tursēnoi), is a hypothetical extinct family of closely related ancient languages proposed by Helmut Rix (1998), that consists of the Etruscan language of central Italy, the Raetic language of the Alps, and the Lemnian language of the Aegean Sea. Camunic in northern Lombardy, in between Etruscan and Raetic, may belong here too, but the material is very scanty.[2]

Evidence

Rix assumes a date for Proto-Tyrsenian of roughly 1000 BC.

Cognates common to Raetic and Etruscan are:

- Etr. zal, Raet. zal, "two";

- Etr. -(a)cvil, Raet. akvil, "gift";

- Etr. zinace, Raet. t'inaχe, "he made".

- a genitive suffix -s in all three languages;

- a second genitive suffix -a in Raetic, -(i)a in Etruscan;

- the past active participle -ce in Etruscan, -ku in Raetic.

Cognates common to Lemnian and Etruscan are:

- dative-case suffixes *-si, and *-ale, attested on the Lemnos Stele (Hulaie-ši "for Hulaie", Φukiasi-ale "for the Phocaean") and in Etruscan inscriptions (e.g. aule-si "To Aule" on the Cippus Perusinus).

- a past tense suffix *-a-i (Etruscan -⟨e⟩ as in ame "was" ( ← *amai); Lemnian -⟨ai⟩ as in šivai "lived").

Strabo's (Geography V, 2), citation from Anticlides attributes to Pelasgians of Lemnos and Imbros a share in the foundation of Etruria.[3][4] The Pelasgians are also referred to by Herodotus as settlers in Lemnos, after they were expelled from Attica by the Athenians.[5] Tyrrhenians anciently in Lemnos are instanced by Apollonius of Rhodes in his Argonautica (IV.1760), written in the 3rd century BC, in an elaborate invented aition of Kalliste/Thera (modern Santorini): in passing he attributes to "Tyrrhenian warriors" in the island of Lemnos the flight of "Sintian" Lemnians to the island Kalliste.

Alternatively the Lemnian language could have arrived in the Aegean Sea during the Late Bronze Age, when Mycenaean rulers recruited groups of mercenaries from Sicily, Sardinia and various parts of the Italian peninsula.[6]

Suggested relationships to other families

Aegean language family

A larger Aegean family including Eteocretan, Minoan and Eteocypriot has been proposed by G.M. Facchetti, and is supported by S. Yatsemirsky in Russia, referring to some alleged similarities between on the one hand Etruscan and Lemnian (a language attested in the Aegean, widely thought to be related to Etruscan), and on the other hand some languages such as Minoan and Eteocretan. If these languages could be shown to be related to Etruscan and Rhaetic, they would constitute a pre-Indo-European family stretching from (at the very least) the Aegean islands and Crete across mainland Greece and the Italian peninsula to the Alps. Facchetti proposes a hypothetical language family derived from Minoan in two branches. From Minoan he proposes a Proto-Tyrrhenian from which would have come the Etruscan, Lemnian and Rhaetic languages. James Mellaart has proposed that this language family is related to the pre-Indo-European Anatolian languages, based upon place name analysis.[7] From another Minoan branch would have come the Eteocretan language.[8][9] T. B. Jones proposed in 1950 reading of Eteocypriot texts in Etruscan, which was refuted by most scholars but gained popularity in the former Soviet Union.

Anatolian languages

A relation with the Anatolian languages within Indo-European has been proposed,[lower-alpha 1][11] but is not generally accepted (although Leonard R. Palmer did show that some Linear A inscriptions were sensible as a variant of Luwian). If these languages are an early Indo-European stratum rather than pre-Indo-European, they would be associated with Krahe's Old European hydronymy and would date back to a Kurganization during the early Bronze Age.

Kartvelian languages

Ancient Etruscan speakers buried within mounds in Tuscany and Veneto in Italy were found to have belonged to be of predominantly Y-DNA Haplogroup G2a extraction. Coincidentally, most Neolithic men in Central Europe were found to belong to G2a as well. The 5,300 year old Chalcolithic mummy Ötzi the Iceman of the Ötztal Alps was found to belong to Haplogroup G2a2. Haplogroup G2a tends to peak in Georgia, as well as other Kartvelians and Caucasian peoples. Ötzi was also found as well to belong to maternal Haplogroup K, which also coincidentally seems to peak very high in Georgians. Ötzi was also proven to have living DNA-tested relatives in modern-day Sardinia, home to some of the oldest peoples and civilizations in Europe.

Genetics may play a role in helping to discovering the origins of Tyrsenian language; and current genetic evidence concludes it is possible that there may have been a Neolithic or Chalcolithic relationship to; or exchange between Tyrsenian and hypothesized Proto-Kartvelian.

Northeast Caucasian languages

A number of mainly Soviet or post-Soviet linguists, including Sergei Starostin,[12] suggested a link between the Tyrrhenian languages and the Northeast Caucasian languages, based on claimed sound correspondences between Etruscan, Hurrian and Northeast Caucasian languages, numerals, grammatical structures and phonologies. This claim was renewed by Ed Robertson (2006).[13]

Extinction

The language group would have died out around the 3rd century BC in the Aegean (by assimilation of the speakers to Greek), and as regards Etruscan around the 1st century AD in Italy (by assimilation to Latin). Finally, Raetic died out in the 3rd century AD, by assimilation to Vulgar Latin in the south and to Germanic in the north.

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ Nordhoff, Sebastian; Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2013). "Etrusco-Rhaetian". Glottolog. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ↑ Blackwell reference.

- ↑ Myres, JL (1907), "A history of the Pelasgian theory", Journal of Hellenic Studies: 169–225,

s. 16 (Pelasgians and Tyrrhenians)

. - ↑ Strabo, Lacus Curtius (public domain translation), Jones, HL transl., U Chicago,

And again, Anticleides says that they (the Pelasgians) were the first to settle the regions round about Lemnos and Imbros, and indeed that some of these sailed away to Italy with Tyrrhenus the son of Atys

. - ↑ Herodotus, The Histories, Perseus, Tufts, 6, 137.

- ↑ De Ligt, Luuk. "AN ‘ETEOCRETAN’ INSCRIPTION FROM PRAISOS AND THE HOMELAND OF THE SEA PEOPLES" (PDF). http://www.talanta.nl. ALANTA XL-XLI (2008-2009), 151-172. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ Mellaart, James (1975), "The Neolithic of the Near East" (Thames and Hudson)

- ↑ Facchetti 2001.

- ↑ Facchetti 2002, p. 136.

- ↑ Steinbauer 1999.

- ↑ Palmer 1965.

- ↑ Starostin, Sergei; Orel, Vladimir (1989). "Etruscan and North Caucasian". In Shevoroshkin, Vitaliy. Explorations in Language Macrofamilies. Bochum Publications in Evolutionary Cultural Semiotics. Bochum.

- ↑ Robertson, Ed (2006), Etruscan’s genealogical linguistic relationship with Nakh–Daghestanian: a preliminary evaluation (PDF), Nostratic.

Sources

- Facchetti, Giulio M (2001), "Qualche osservazione sulla lingua minoica" [Some observations on the Minoican language], Kadmos (in Italian) 40: 1–38.

- ——— (2002), "Appendice sulla questione delle affinità genetiche dell'Etrusco" [Appendix on questions of the Etruscan genetic affinity], Appunti di morfologia etrusca (in Italian) (Leo S. Olschki): 111–50, ISBN 88-222-5138-5.

- Palmer, LR (1965), Mycenaeans and Minoans (2nd ed.), New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Rix, Helmut (1998), Rätisch und Etruskisch [Raetian & Etruscan] (in German), Innsbruck.

- Steinbauer, Dieter H (1999), Neues Handbuch des Etruskischen [New handbook on Etruscan] (in German), St. Katharinen.

- Schumacher, Stefan (1998), "Sprachliche Gemeinsamkeiten zwischen Rätisch und Etruskisch", Der Schlern (in German) 72: 90–114.

- ——— (2004), "Die rätischen Inschriften. Geschichte und heutiger Stand der Forschung. 2. erweiterte Auflage", Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Kulturwissenschaft (in German) (Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachen und Literaturen der Universität Innsbruck), 121 = Archaeolingua 2.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||