Aegean dispute

The Aegean dispute is a set of interrelated controversial issues between Greece and Turkey over sovereignty and related rights in the area of the Aegean Sea. This set of conflicts has had a large effect on Greek-Turkish relations since the 1970s. It has twice led to crises coming close to the outbreak of military hostilities, in 1987 and in early 1996. The issues in the Aegean fall into several categories:

- The delimitation of the territorial waters,

- The delimitation of the national airspace,

- The delimitation of exclusive economic zones and the use of the continental shelf,

- The delimitation of Flight Information Regions (FIR), and their significance for the control of military flight activity,

- The issue of the demilitarized status assigned to some of the Greek islands in the area,

- Turkish claims of "grey zones" of undetermined sovereignty over a number of small islets, most notably the islets of Imia/Kardak.

Since 1998, the two countries have been coming closer to overcome the tensions through a series of diplomatic measures, particularly with a view to easing Turkey's accession to the European Union. However, as of 2010, differences over suitable diplomatic paths to a substantial solution are still unresolved.

Maritime and aerial zones of influence

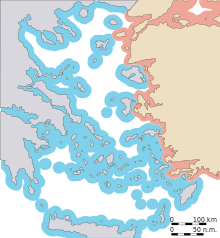

Several of the Aegean issues deal with the delimitation of both countries' zones of influence in the air and on the sea around their respective territories. These issues owe their virulence to a geographical peculiarity of the Aegean sea and its territories. While the mainland coasts of Greece and Turkey bordering the Aegean Sea on both sides represent roughly equal shares of its total coastline, the overwhelming number of the many Aegean islands belong to Greece. In particular, there is a chain of Greek islands lined up along the Turkish west coast (Lesbos, Chios, Samos, and the Dodecanese islands), partly in very close proximity to the mainland. Their existence blocks Turkey from extending any of its zones of influence beyond a few nautical miles off its coastline. As the breadth of maritime and areal zones of influence, such as the territorial waters and national airspace, are measured from the nearest territory of the state in question, including its islands, any possible extension of such zones would necessarily benefit Greece much more than Turkey proportionally.

According to a popular perception of these issues in the two countries, Turkey is concerned that Greece might be trying to extend its zones of influence to such a degree that it would turn the Aegean effectively into a "Greek lake". Conversely, Greece is concerned that Turkey might try to "occupy half of the Aegean", i.e. establish Turkish zones of influence towards the middle of the Aegean, beyond the chain of outlying Greek islands, turning these into a kind of exclave surrounded by Turkish waters, and thus cutting them off from their motherland.[1]

Territorial waters

Territorial waters give the littoral state full control over air navigation in the airspace above, and partial control over shipping, although foreign ships (both civil and military) are normally guaranteed innocent passage through them. The standard width of territorial waters that countries are customarily entitled to has steadily increased in the course of the 20th century: from initially 3 nautical miles (5.6 km) at the beginning of the century, to 6 nautical miles (11 km), and currently 12 nautical miles (22 km). The current value has been enshrined in treaty law by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 1982 (Art.3). In the Aegean the territorial waters claimed by both sides are still at 6 miles. The possibility of an extension to 12 miles has fuelled Turkish concerns over a possible disproportionate increase in Greek-controlled space. Turkey has refused to become a member of the convention and does not consider itself bound by it. Turkey considers the convention as res inter alios acta, i.e. a treaty that can only be binding to the signing parties but not to others. Greece, which is a party to the convention, has stated that it reserves the right to apply this rule and extend its waters to 12 miles at some point in the future, although it has never actually attempted to do so. It holds that the 12 mile rule is not only treaty law but also customary law, as per the wide consensus established among the international community. Against this, Turkey argues that the special geographical properties of the Aegean Sea make a strict application of the 12 mile rule in this case illicit in the interest of equity.[2] Turkey has itself applied the customary 12 mile limit to its coasts outside the Aegean.

Tensions over the 12 mile question ran highest between the two countries in the early 1990s, when the Law of the Sea was going to come into force. On 9 June 1995, the Turkish parliament officially declared that unilateral action by Greece would constitute a casus belli, i.e. reason to go to war. This declaration has been condemned by Greece as a violation of the Charter of the United Nations, which forbids "the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state".[1]

National airspace

The national airspace is normally defined as the airspace covering a state's land territory and its adjacent territorial waters. National airspace gives the sovereign state a large degree of control over foreign air traffic. While civil aviation is normally allowed passage under international treaties, foreign military and other state aircraft (unlike military vessels in the territorial waters) do not have a right to free passage through another state's national airspace.[3] The delimitation of national airspace claimed by Greece is unique, as it does not coincide with the boundary of the territorial waters. Greece claims 10 nautical miles (19 km) of airspace, as opposed to currently 6 miles of territorial waters. Since 1974, Turkey has refused to acknowledge the validity of the outer 4-mile belt of airspace that extends beyond the Greek territorial waters. Turkey cites the statutes of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) of 1948, as containing a binding definition that both zones must coincide.[4] Against this, Greece argues that:

- its 10-nautical-mile (19 km) claim predates the ICAO statute, having been fixed in 1931, and that it was acknowledged by all its neighbours, including Turkey, before and after 1948, hence constituting an established right;[5]

- its 10-mile claim can also be interpreted as just a partial, selective use of the much wider rights guaranteed by the Law of the Sea, namely the right to a 12-mile zone both in the air and on the water;

- Greek territorial waters are set at the 6 mile boundary only because of Turkey's casus belli.

The conflict over military flight activities has led to a practice of continuous tactical military provocations, with Turkish aircraft flying in the outer 4 mile zone of contentious airspace and Greek aircraft intercepting them. These encounters often lead to so-called "dog-fights", dangerous flight maneuvers that have repeatedly ended in casualties on both sides. In one instance in 1996, it has been alleged that a Turkish plane was accidentally shot down by a Greek one.[6]

Continental shelf

In the context of the Aegean dispute, the term continental shelf refers to a littoral state's exclusive right to economic exploitation of resources on and under the sea-bed, for instance oil drilling, in an area adjacent to its territorial waters and extending into the High Seas. The width of the continental shelf is commonly defined for purposes of international law as not exceeding 200 nautical miles. Where the territories of two states lie closer opposite each other than double that distance, the division is made by the median line. The concept of the continental shelf is closely connected to that of an exclusive economic zone, which refers to a littoral state's control over fishery and similar rights. Both concepts were developed in international law from the middle of the 20th century, and were codified in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea in 1982.

The dispute between Turkey and Greece is to what degree the Greek islands off the Turkish coast should be taken into account for determining the Greek and Turkish economic zones. Turkey argues that the notion of "continental shelf", by its very definition, implies that distances should be measured from the continental mainland, claiming that the sea-bed of the Aegean geographically forms a natural prolongation of the Anatolian land mass. This would mean for Turkey to be entitled to economic zones up to the median line of the Aegean (leaving out, of course, the territorial waters around the Greek islands in its eastern half, which would remain as Greek exclaves.) Greece, on the other hand, claims that all islands must be taken into account on an equal basis. This would mean that Greece would gain the economic rights to almost the whole of the Aegean.[2]

In this matter, Greece has the UN Law of the Sea on its side, although the Convention restricts the application of this rule to islands of a notable size, as opposed to small uninhabitable islets and rocks. The precise delimitation of the economic zones is the only one of all the Aegean issues where Greece has officially acknowledged that Turkey has legitimate interests that might require some international process of arbitration or compromise between the two sides.[5]

Tensions over the continental shelf were particularly high during the mid-1970s and again the late 1980s, when it was believed that the Aegean Sea might hold rich oil reserves. Turkey at that time conducted exploratory oceanographic research missions in parts of the disputed area. These were perceived as a dangerous provocation by Greece, which led to a buildup of mutual military threats in 1976 and again in 1987.[5]

Flight Information Regions

Unlike the issues described so far, the question of Flight Information Regions (FIR) does not affect the two states' sovereignty rights in the narrow sense. A FIR is a zone of responsibility assigned to a state within the framework of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). It relates to the responsibility for regulating civil aviation. A FIR may stretch beyond the national airspace of a country, i.e. over areas of high seas, or in some cases even over the airspace of another country. It does not give the responsible state the right to prohibit flights by foreign aircraft; however, foreign aircraft are obliged to submit flight plans to the authorities administrating the FIR. Two separate disputes have arisen over flight control in the Aegean: the issue of a unilaterally proposed revision of the FIR demarcation, and the question of what rights and obligations arise from the FIR with respect to military as opposed to civil flights.

Demarcation

By virtue of an agreement signed in 1952, the whole airspace over the Aegean, up to the boundary of the national airspace of Turkey, has been assigned to Athens FIR, administered by Greece. Shortly after the Cyprus crisis of 1974, Turkey unilaterally attempted to change this arrangement, issuing a Notice to Airmen (NOTAM) stating that it would take over the administration of the eastern half of the Aegean airspace, including the national airspace of the Greek islands in that area. Greece responded with a declaration rejecting this move, and declaring the disputed zone unsafe for aviation due to the conflicting claims to authority. This led to some disruption in civil aviation in the area. Turkey later changed its stance, and since 1980 has returned to recognizing Athens FIR in its original demarcation.[5] In practice, the FIR demarcation is currently no longer a disputed issue.

Turkish Military overflights

The current (as of 2009) controversy over the FIR relates to the question whether the Greek authorities have a right to oversee not only civil but also military flight activities in the international parts of the Aegean airspace. According to common international practice, military aircraft normally submit flight plans to FIR authorities when moving in international airspace, just like civil aircraft do. Turkey refuses to do so, citing the ICAO charter of 1948, which explicitly restricts the scope of its regulations to civil aircraft, arguing that therefore the practice of including military aircraft in the same system is optional. Greece, in contrast, argues that it is obligatory on the basis of later regulations of the ICAO, which it claims have given states the authority to issue more wide-reaching restrictions in the interest of civil aviation safety.

This disagreement has led to similar practical consequences as the issue of 6 versus 10 miles of national airspace, as Greece considers all Turkish military flights not registered with its FIR authorities as transgressions of international air traffic regulations, and routinely has its own air force jets intercepting the Turkish ones. In popular perception in Greece, the issue of Turkish flights in the international part of Athens FIR is often confused with that of the Turkish intrusions in the disputed outer 4 mile belt of Greek airspace. However, in careful official usage, Greek authorities and media distinguish between "violations" ("παραβιάσεις") of the national airspace, and "transgressions" ("παραβάσεις") of traffic regulations, i.e. of the FIR.

One of the routine interception maneuvers led to a fatal accident on 23 May 2006. Two Turkish F-16s and one reconnaissance F-4 were flying in the international airspace over the southern Aegean at 27,000 feet (8,200 m) without having submitted flight plans to the Greek FIR authorities. They were intercepted by two Greek F-16s off the coast of the Greek island Karpathos. During the ensuing mock dog fight, a Turkish F-16 and a Greek F-16 collided midair and subsequently crashed. The pilot of the Turkish plane survived the crash, but the Greek pilot died. The incident also highlighted another aspect of the FIR issue, a dispute over conflicting claims to responsibility for maritime search and rescue operations. The Turkish pilot reportedly refused to be rescued by the Greek forces that had been dispatched to the area. After the incident, both governments expressed an interest to revive an earlier plan of establishing a direct hotline between the air force commands of both countries in order to prevent escalation of similar situations in the future.

Islands

While all the issues described so far are related to zones of influence at sea or in the air, there have also been a number of disputes related to the territories of the Greek islands themselves. These have related to the demilitarized status of some of the main islands in the area; to Turkish concerns over alleged endeavours by Greece to artificially expand settlements to previously uninhabited islets; and to the existence of alleged "grey zones", an undetermined number of small islands of undetermined sovereignty.

Demilitarized status

The question of the demilitarized status of some major Greek islands is complicated by a number of facts. Several of the Greek islands in the eastern Aegean as well as the Turkish straits region were placed under various regimes of demilitarization in different international treaties. The regimes developed over time, resulting in difficulties of treaty-interpretation. The military status of the islands in question did however not constitute a serious problem in the bilateral relations until the Cyprus crisis of 1974, after which both Greece and Turkey re-interpreted the stipulations of the treaties. Greece, claiming an inalienable right to defend itself against Turkish aggression, reinforced its military and National Guard forces in the region. Turkey, on the other hand, denounces this as an aggressive act by Greece and as a breach of international treaties.[4] From a legal perspective, three groups of islands may be distinguished: (a) the islands right off the Turkish Dardanelles straits, i.e. Lemnos and Samothrace; (b) the Dodecanese islands in the southeast Aegean; and (c) the remaining northeast Aegean islands (Lesbos, Chios, Samos, and Ikaria).

Lemnos and Samothrace

These islands were placed under a demilitarization statute by the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, to counterbalance the simultaneous demilitarization of the Turkish straits area (the Dardanelles and Bosphorus), Imbros and Tenedos. The demilitarization on the Turkish side was later abolished through the Montreux Convention Regarding the Regime of the Turkish Straits in 1936. Greece holds that, by superseding the relevant sections of the earlier treaty, the convention simultaneously lifted also the Greek obligations with respect to these islands. Against this, Turkey argues that the Montreux treaty did not mention the islands and has not changed their status.[4] Greece, on the other hand, cites Turkish official declarations, by the then Turkish Minister for Foreign Affairs, Rustu Aras, to that effect made in 1936,[7] assuring the Greek side that Turkey would consider the Greek obligations lifted.[5]

Dodecanese

These islands were placed under a demilitarization statute after the Second World War by the Treaty of peace with Italy (1947), when Italy ceded them to Greece. Italy had previously not been under any obligation towards Turkey in this respect. Turkey, in turn, was not a party to the 1947 treaty, having been neutral during WWII. Greece therefore holds that the obligations it incurred towards Italy and the other parties in 1947 are res inter alios acta for Turkey in the sense of Article 34 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, which states that a treaty does not create obligations or rights for a third country, and that Turkey thus cannot base any claims on them. Turkey argues that the demilitarization agreement constitutes a status treaty (an objective régime), where according to general rules of treaty law such an exclusion does not hold.

Lesbos, Chios, Samos, and Ikaria

The remaining islands (Lesbos, Chios, Samos, and Ikaria) were placed under a partial demilitarization statute by the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923. It prohibited the establishment of naval bases and fortifications, but allowed Greece to maintain a limited military contingent recruited from the local population, as well as police forces. With respect to these islands, Greece has not claimed that the treaty obligations have been formally superseded. However, in recent years it has argued that it is entitled to discount them, invoking Article 15 of the Charter of the United Nations. It argues that after the Turkish occupation of northern Cyprus and the Turkish threat of war over the 12 miles issue, re-armament is an act of legitimate self-defence.[5]

"Grey zones"

Imia/Kardak

The first time a dispute between the two countries in the Aegean touched on questions of actual sovereignty over territories was in early 1996 at the tiny barren islets of Imia/Kardak, situated between the Dodecanese island chain and the Turkish mainland.[8] The conflict, triggered by the stranding of a Turkish merchant ship on the islets, was originally caused by factual inconsistencies between maps of the area, some of which assigned these islets to Greece, others to Turkey. The media of the two countries took up the issue and gave it a nationalistic turn, before the two governments even had the time to come to a full technical understanding of the true legal and geographical situation. Both governments finally adopted an intransigent stance, publicly asserting their own claims of sovereignty over the islets. The result was military escalation, which was perceived abroad as quite out of proportion with the size and significance of the rocks in question. The two countries were at the brink of war for a few days, until the crisis was defused with the help of foreign mediation.[9]

During the crisis and in the months following it, both governments elaborated legal arguments to support their claims to sovereignty. The arguments exchanged concerned the interpretation of the Treaty of Lausanne of 1923, which forms the principal basis for the legal status of territories in most of the region, as well as certain later diplomatic dealings between Turkey, Greece and Italy.

Other "grey zones"

In the wake of the Imia crisis, the Turkish government widened its argumentation to include not only Imia but also a possibly large number of other islands and small formations across the Aegean. Since then, Turkish authorities have spoken of "grey zones" of undetermined sovereignty. According to the Turkish argument, these islets, while not explicitly retained under Turkish sovereignty in 1923, were also not explicitly ceded to any other country, and their sovereignty has therefore remained objectively undecided.

The Turkish government has avoided stating exactly which islets it wishes to include in this category. On various occasions, Turkish government sources have indicated that islands such as Pserimos, Agathonisi, Fournoi and Gavdos[10] (situated south of Crete) might be included. Most of them, unlike Imia/Kardak, had undeniably been in factual Greek possession, which had never previously been challenged by Turkey, and many are inhabited. In a 2004 publication by Turkish authors close to the Turkish military leadership[11] the following (among other, even smaller ones) were listed as potentially "grey" areas:

- Kalogeroi,

- Antipsara (west of the islands of Psara and Khios),

- Pontiko (between Samos and the Turkish coast),

- Fournoi,

- Arkoi,

- Agathonisi (Gaidaros),

- Pharmakonisi,

- Kalolimnos (near Imia/Kardak),

- Pserimos,

- Gyali (between Kos and Nisyros),

- Kandheliousa (south of Kos),

- Sirina (SE of Astypalaia)

While Turkey has not made any attempt at challenging the Greek possession of these islands on the ground, the claims add to the number of minor military incidents, already numerous due to the 10-mile airspace and the FIR issues. The Turkish Air Force has reportedly adopted a policy of ignoring Greek claims to all airspace and territorial waters around such formations that it counts as grey zones. According to Greek press reports, the number of airspace violations within the 6-mile limit recognised by Ankara rose sharply in 2006, as did the number of unauthorised Turkish military flights directly over Greek islands themselves.[12] Renewed reports of systematic Turkish military flights directly over Greek islands like Pharmakonisi and Agathonisi were made in late 2008 and early 2009.[13]

Turkish incidents with Frontex

In September 2009, a Turkish military radar issued a warning to a Latvian helicopter patrolling in the eastern Aegean—part of the EU's Frontex programme to combat illegal immigration—to leave the area. The Turkish General Staff reported that the Latvian Frontex aircraft had violated Turkish airspace west of Didim.[14] According to a Hellenic Air Force announcement, the incident occurred as the Frontex helicopter—identified as an Italian-made Agusta A109—was patrolling in Greek air space near the small isle of Farmakonisi, which lies on a favorite route used by migrant smugglers ferrying mostly Third World migrants into Greece and the EU from the opposite Turkish coastline.[15] Frontex officials stated that they simply ignored the Turkish warnings as they did not recognise their being in Turkish airspace and continued their duties.

Another incident took place on October 2009 in the aerial area above the eastern Aegean sea, off the island of Lesbos.[16] On 20 November 2009, the Turkish General Staff issued a press note alleging that an Estonian Border Guard aircraft Let L-410 UVP taking off from Kos on a Frontex mission had violated Turkish airspace west of Söke.[14]

Strategies of conflict resolution

The decades since the 1970s have seen a repeated heightening and abating of political and military tensions over the Aegean. Thus, the crisis of 1987 was followed by a series of negotiations and agreements in Davos and Brussels in 1988. Again, after the Imia/Kardak crisis of 1996, there came an agreement over peaceful neighbourly relations reached at a meeting in Madrid in 1997. The period since about 1999 has been marked by a steady improvement of bilateral relations.

For years, the Aegean dispute has been a matter not only about conflicting claims of substance. Rather, proposed strategies of how to resolve the substantial differences have themselves constituted a matter of heated dispute. Whereas Turkey has traditionally preferred to regard the whole set of topics as a political issue, requiring bilateral political negotiation,[1] Greece views them as separate and purely legal issues, requiring only the application of existing principles of international law. Turkey has advocated direct negotiation, with a view to establishing what it would regard as an equitable compromise. Greece refuses to accept any process that would put it under pressure to engage in a give-and-take over what it perceives as inalienable and unnegotiable sovereign rights. Up to the late 1990s, the only avenue of conflict resolution that Greece deemed acceptable was to submit the issues separately to the International Court of Justice in The Hague.

The resulting stalemate between both sides over process was partially changed after 1999, when the European summit of Helsinki opened up a path towards Turkey's accession to the EU. In the summit agreement, Turkey accepted an obligation to solve its bilateral disputes with Greece before actual accession talks would start. This was perceived as giving Greece a new tactical advantage over Turkey in determining which paths of conflict resolution to choose. During the following years, both countries held regular bilateral talks on the level of technical specialists, trying to determine possible future procedures. According to press reports , both sides seemed close to an agreement about how to submit the dispute to the court at The Hague, a step which would have fulfilled many of the old demands of Greece. However, a newly elected Greek government under Kostas Karamanlis, soon after it took office in March 2004, opted out of this plan, because Ankara was insisting that all the issues, including Imia/Kardak and the "grey zones", belonged to a single negotiating item. Athens saw them as separate.[17] However, Greek policy remained at the forefront in advocating closer links between Ankara and the EU. This resulted in the European Union finally opening accession talks with Turkey without its previous demands having been fulfilled.

See also

- Cyprus dispute

- Cyprus–Turkey maritime zones dispute

- Foreign relations of Greece

- Foreign relations of Turkey

References

- 1 2 3 Kemal Başlar (2001): Two facets of the Aegean Sea dispute: 'de lege lata' and 'de lege ferenda'. In: K. Başlar (ed.), Turkey and international law. Ankara.

- 1 2 Wolff Heintschel von Heinegg (1989): Der Ägäis-Konflikt: Die Abgrenzung des Festlandsockels zwischen Griechenland und der Türkei und das Problem der Inseln im Seevölkerrecht. Berlin: Duncker und Humblot. (German)

- ↑ Haanappel, Peter P. C. (2003). The Law and Policy of Air Space and Outer Space. Kluwer. p. 22.

- 1 2 3 Embassy of Turkey in Washington: Aegean Disputes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs: Unilateral Turkish claims in the Aegean.

- ↑ The incident was first described as an accident. In 2004, a Greek newspaper published claims that the Turkish plane had unintentionally been shot down by the Greek one. The shootdown was confirmed by the Turkish government but denied by the Greek side .

- ↑ Gazette of the Minutes of the Turkish National Assembly, volume 12. 31 July 1936, page 309

- ↑ Sezgin, I.Can (2009): Why they did not fight? A Study on the Imia/ Kardak Crisis (1995–1996) between Greece and Turkey, http://uni-tuebingen.academia.edu/IbrahimCanSezgin/Papers/138642/Why_they_did_not_fight_Kardak-Imia_Crisis_1995-1996

- ↑ Ch. Maechling (1997): The Aegean sea: a crisis waiting to happen. US Naval Institute Proceeding 71–73.

- ↑ Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs statement on the Gavdos issue

- ↑ (Major)Ali Kurumahmut, Sertaç Başeren (2004): The twilight zones in the Aegean: (Un)forgotten Turkish islands. Ege'de gri bölgeler: Unutul(may)an Türk adaları. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu. (ISBN 975-16-1740-5). (Turkish)

- ↑ Νίκος Μελέτης (26 January 2008). "Στις γκρίζες ζώνες και το μειονοτικό...". Το Έθνος.

- ↑ Η Τουρκία θέλει "γκρίζα" τετελεσμένα. To Vima (in Greek). 9 January 2009. Retrieved 9 January 2009.

- 1 2 "Airspace violations in the Aegean". Archived from the original on 12 March 2010.

- ↑ "Latest Frontex patrol harassed". Archived from the original on 12 September 2009. Retrieved 14 September 2009.

- ↑ "Newest Frontex patrol harassed". Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ↑ A. Papachelas: "'Γκρίζες ζώνες' στις διαπραγματεύσεις με την Αγκυρα". Το Βήμα της Κυριακής, 16 May 2004. (Greek)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||