Vestry

A vestry refers to a robing and storage room in or attached to a place of worship.

It also referred in England and Wales to the committee for secular and church government for a parish which met in the vestry of the parish church, and consequently became known colloquially as the "vestry".

Vestry (room)

A vestry is a room in a church or synagogue in which the vestments are kept, and in which the clergy and choir don these liturgical clothes for worship services. Valuable or sacred items such as communion vessels or collection plates may be kept there, usually in a secure safe, along with official records such as registers of marriages and burials.

In Welsh chapels, the room is often the location of a tea served to the congregation, particularly family members, after a funeral, when the congregation returns to the chapel after the burial or cremation.

Vestry committees in England and Wales

The vestry was a meeting of the parish ratepayers chaired by the incumbent of the parish, originally held in the parish church or its vestry, from which it got its name.[2]

The vestry committees were not established by any law, but they evolved independently in each parish according to local needs from their roots in medieval parochial governance. By the late 17th century they had become, along with the county magistrates, the rulers of rural England.[3]

In England, until the 19th century, the parish vestry committee was in effect what would today usually be called a parochial church council, but was also responsible for secular parish business, which is now the responsibility of a parish council, and other activities, such as administering locally the poor law.

Origins

The original unit of settlement among the Anglo-Saxons in England was the tun or town. The inhabitants met to carry out this business in the town moot or meeting, at which they appointed the various officials and the common law would be promulgated. Later with the rise of the shire, the township would send its reeve and four best men to represent it in the courts of the hundred and shire. However, this local independence of the Saxon system was lost to the township by the introduction of the feudal manorial Court Leet which replaced the town meeting.

The division into ancient parishes was linked to the manorial system, with parishes and manors often sharing the same boundaries.[4] Initially, the manor was the principal unit of local administration and justice in the rural economy, but over time the Church replaced the manorial court as the centre of rural administration, and levied a local tax on produce known as a tithe.[4] The decline of the feudal system and, following the Reformation in the 16th century, the power of the Church, led to a new form of township or parish meeting, which dealt with both civil and ecclesiastical affairs. This new meeting was supervised by the parish priest, probably the best educated of the inhabitants, and it evolved to become the vestry meeting.[5]

Growth of power

With the decay of the feudal system, the vestry meetings gradually acquired greater responsibilities; such as having the power to grant or deny payments from parish funds. Although the vestry committees were not established by any law, and had come into being in an unregulated ad-hoc process, it was highly convenient to give them the task of administering the Edwardian and Elizabethan systems for support of the poor. This was their first, and for many centuries their principal statutory power. With this gradual formalisation of civil responsibilities, the ecclesiastical parishes acquired a dual nature and could be classed as both civil and ecclesiastical parishes. In England, until the 19th century, the parish vestry was in effect what would today usually be called a parochial church council, but was also responsible for all the secular parish business now dealt with by civil bodies, such as parish councils.

Eventually, the vestry had a number of legal obligations. The vestry was responsible for appointing parish officials, such as the parish clerk, overseers of the poor, sextons and scavengers, constables and nightwatchmen.

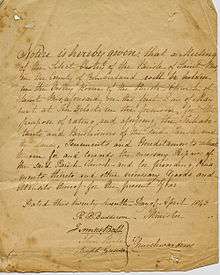

The decisions and accounts of the vestry committee would be administered by the parish clerk, and records of parish business would be stored in a "parish chest" kept in the church and provided for security with three different locks, the individual keys to which would be held by such as the parish priest and churchwardens.

In 1835 more than 15,600 ecclesiastical parish vestries looked after their own: churches and burial grounds, parish cottages and workhouses, their common lands and endowed charities, their market crosses, pumps, pounds, whipping posts, stocks, cages, watch houses, weights and scales, clocks and fire engines. Or to put it another way: the maintenance of the church and its services, the keeping of the peace, the repression of vagrancy, the relief of destitution, the mending of roads, the suppression of nuisances, the destruction of vermin, the furnishing of soldiers and sailors, even to some extent the enforcement of religious and moral discipline. These were among the multitudinous duties imposed on the parish and its officers, that is to say the vestry and its organisation, by the law of the land.

At the high point of their powers, just prior to removal of Poor Law responsibilities in 1834, the vestries spent not far short of one-fifth of the budget of the national government itself.[5]

The select vestry

Whilst the vestry was a general meeting of all inhabitant rate-paying householders in a parish,[6] in the 17th Century the huge growth of population in some parishes, mostly urban, made it increasingly difficult to convene and conduct meetings. Consequently, in some of these a new body, the Select Vestry, was created. This was an administrative committee of selected parishioners whose members generally had a property qualification and who were recruited largely by co-option.[6] This took responsibility from the community at large and improved efficiency, but over time tended to lead to governance by a self-perpetuating elite.[4] This committee was also known as the "close vestry", and the term "open vestry" was used for the meeting of all ratepayers.

By the late 17th century, the existence of a number of autocratic and corrupt select vestries had become a national scandal, and several bills were introduced to parliament in the 1690s, but none became acts. There was continual agitation for reform, and in 1698 to keep the debate alive the House of Lords insisted that a bill to reform the select vestries, the Select Vestries Bill, would always be the first item of business of the Lords in a new parliament until a reform bill was passed. The first reading of the bill was made annually, but every year the bill never got any further. This continues to this day as an archaic custom in the Lords to assert the independence from the Crown, even though the select vestries have long been abolished.[3]

Decline

A major responsibility of the vestry had been the administration of the Poor Law, but the widespread unemployment following the Napoleonic Wars overwhelmed the vestries, and under the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 this duty was transferred to elected boards of guardians for single parishes or to poor law unions for larger areas. These new bodies now received the poor law levy and administered the system, and removed a large portion of the income of the vestry and a significant part of its duties.

The vestries escaped the Municipal Corporations Act 1835, which brought more democratic and open processes to municipal bodies, but there was gradual movement to separate the vestry's ecclesiastical and secular duties. The Vestries Act 1850 prevented the holding of meeting in churches, and in London, vestries were incorporated under the Metropolis Management Act 1855 to create properly regulated civil bodies for London parishes, but they did not have any ecclesiastical duties.

As the 19th century progressed the parish vestry progressively lost its secular duties to the increasing number of local boards which came into being and operated across greater areas than single parishes for a specific purpose. These were able to levy their own rate. Among these were the local boards of health created under the Public Health Act 1848, the Burial boards, which took over responsibility for secular burials in 1853, and the Sanitary Districts which were established in 1875. The church rate ceased to be levied in many parishes and was made voluntary in 1868.[7]

However, the proliferation of these local bodies led to a confusing fragmentation of local government responsibilities, and this became a driver for large scale reform in local government, which resulted in the Local Government Act 1894. The problem of so many local bodies was expressed by H H Fowler, President of the Local Government Board, who said in the parliamentary debate for the 1894 Act....

| “ | 62 counties, 302 Municipal Boroughs, 31 Improvement Act Districts, 688 Local Government Districts, 574 Rural Sanitary Districts, 58 Port Sanitary Districts, 2,302 School Board Districts ... 1,052 Burial Board Districts, 648 Poor Law Unions, 13,775 Ecclesiastical Parishes, and nearly 15,000 Civil Parishes. The total number of Authorities which tax the English ratepayers is between 28,000 and 29,000. Not only are we exposed to this multiplicity of authority and this confusion of rating power, but the qualification, tenure, and mode of election of members of these Authorities differ in different cases."[8] | ” |

Under the Act, secular and ecclesiastical duties were finally separated when a system of elected rural parish councils and urban district councils was introduced. This removed all secular matters from the parish vestries, and created parish councils or parish meetings to manage these. The parish vestries were left with only with church affairs to manage.

Ecclesiastical use today

Following the removal of civil powers in 1894, the vestry meetings continued to administer church matters in Church of England parishes until the Parochial Church Councils (Powers) Measure 1921 Act.[9] established parochial church councils as their successors on church matters. Since then, the only remnant of the vestry meeting has been the meeting of parishioners, which is convened annually solely for the election of churchwardens of the ecclesiastical parish.[10] This is sometime referred to as the "annual vestry meeting". All other roles of the vestry meetings are now undertaken by parochial church councils.

The term vestry continues to be used in some other denominations for a body of lay members elected by the congregation to run the business of a church parish, such as in the Scottish [11] and American Episcopal Churches.

Legislation

The Vestries Acts 1818 to 1853 is the collective title of the following Acts:[12]

- The Vestries Act 1818 (58 Geo 3 c 69)

- The Vestries Act 1819 (59 Geo 3 c 85)

- The Vestries Act 1831 (1 & 2 Will 4 c 60)

- The Parish Notices Act 1837 (7 Will 4 & 1 Vict c 45)

- The Vestries Act 1850 (13 & 14 Vict c 57)

- The Vestries Act 1853 (16 & 17 Vict c 65)

See also

References

- ↑ Parish Notices Act 1837

- ↑ The Companion to British History. Charles Arnold-Baker, 2nd edition 2001, Routledge.

- 1 2 Parish Government 1894-1994. KP Poole & Bryan Keith-Lucas. National Association of Local Councils 1994

- 1 2 3 Arnold-Baker, Charles (1989). Local Council Administration in English Parishes and Welsh Communities. Longcross Press. ISBN 978-0-902378-09-4.

- 1 2 Webb, Sidney; Potter, Beatrice (1906), English Local Government from the Revolution to the Municipal Corporations, London: Longmans, Green & Co.

- 1 2 Tate, William Edward (1969), The Parish Chest: a study of the records of parochial administration in England (3rd ed.), Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Arnold-Baker on Local Council Administration, 1989

- ↑ "Local Government of England and Wales Bill". Hansard 1803 - 2005. Parliament of the United Kingdom. 21 March 1893. Retrieved 2009-02-18.

- ↑ - Parochial Church Councils Measure 1921

- ↑ "Churchwardens Measure 2001 No. 1". Legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 24 August 2008.

- ↑ The vestry duties in the Scottish Episcopal Church

- ↑ The Short Titles Act 1896, section 2(1) and Schedule 2