Adlai Stevenson I

| Adlai Stevenson I | |

|---|---|

| |

| 23rd Vice President of the United States | |

|

In office March 4, 1893 – March 4, 1897 | |

| President | Grover Cleveland |

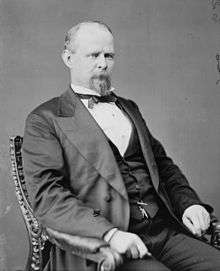

| Preceded by | Levi P. Morton |

| Succeeded by | Garret Hobart |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Illinois's 13th district | |

|

In office March 4, 1875 – March 4, 1877 | |

| Preceded by | John McNulta |

| Succeeded by | Thomas F. Tipton |

|

In office March 4, 1879 – March 4, 1881 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas F. Tipton |

| Succeeded by | Dietrich C. Smith |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Adlai Ewing Stevenson October 23, 1835 Christian County, Kentucky |

| Died |

June 14, 1914 (aged 78) Chicago, Illinois |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Letitia Green Stevenson |

| Children | 4 |

| Alma mater |

Illinois Wesleyan University Centre College |

| Religion | Presbyterian |

| Signature |

|

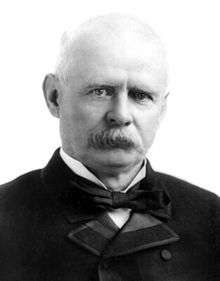

Adlai Ewing Stevenson I (October 23, 1835 – June 14, 1914) served as the 23rd Vice President of the United States (1893–97). Previously, he served as a Congressman from Illinois in the late 1870s and early 1880s. After his subsequent appointment as Assistant Postmaster General of the United States during Grover Cleveland's first administration (1885–89), he fired many Republican postal workers and replaced them with Southern Democrats. This earned him the enmity of the Republican-controlled Congress, but made him a favorite as Grover Cleveland's running mate in 1892, and he duly became Vice President of the United States.

In office, he supported the free-silver lobby against the gold-standard men like Cleveland, but was praised for ruling in a dignified, non-partisan manner.

In 1900, he ran for Vice President with William Jennings Bryan.[1] Although unsuccessful, he was the first ex-Vice President ever to win re-nomination for that post with a different presidential candidate. Stevenson was the grandfather of Adlai Stevenson II, a Governor of Illinois and the unsuccessful Democratic presidential candidate in both 1952 and 1956.

Ancestry

Adlai Ewing Stevenson was born in Christian County, Kentucky, on October 23, 1835, to John Turner and Eliza Ewing Stevenson, Wesleyans of Scots-Irish descent. The Stevenson family is first recorded (as the Stephensons) in Roxburghshire, Scotland, in the early 18th century. The family appears to have been of some wealth, as a private chapel in the Archdiocese of St Andrews bears their name. At some point, probably shortly after the Jacobite rising of 1715, the family migrated to County Antrim, Ireland, near Belfast. At least one Stephenson was a police officer. William Stephenson, the great-grandfather of Adlai, was a tailor who specialized in millinery. After William's father died in the 1730s, his family moved to Lancaster County, Province of Pennsylvania; William joined when his apprenticeship was completed in 1748.[2]

In 1762, the family moved to North Carolina in what is now Iredell County. Including lands given to his children, William Stephenson (Stevenson after the American Revolution) had amassed 3,400 acres (1,400 ha) of land by the time of his death.[3] The family then moved to Kentucky in 1813.

Early life

Stevenson was born on the family farm in Christian County. He attended a public school in Blue Water, Kentucky. In 1850, when he was 14, frost killed the family's tobacco crop. Two years later, his father set free their few slaves and the family moved to Bloomington, Illinois, where his father then operated a sawmill. Stevenson attended Illinois Wesleyan University at Bloomington and ultimately graduated from Centre College, in Danville, Kentucky; at the latter he was a part of Phi Delta Theta. His father's death prompted Stevenson to return from Kentucky to Illinois to run the sawmill.

Stevenson was admitted to the bar in 1858, at age 23, and commenced practice at Metamora in Woodford County, Illinois. As a young lawyer, Stevenson encountered such celebrated Illinois attorneys as Stephen A. Douglas and Abraham Lincoln, campaigning for Douglas in his 1858 Senate race against Lincoln. Stevenson's dislike of Lincoln might have been prompted by a contentious meeting between the two, at which Lincoln made several witty quips disparaging Stevenson.[4] Stevenson also made speeches against the "Know-Nothing" movement, a nativist group opposed to immigrants and Catholics. That stand helped cement his support in Illinois' large German and Irish communities. In a predominantly Republican area, the Democratic Stevenson won friends through his storytelling and his warm and engaging personality.

Marriage and political life, 1860–1884

Stevenson was appointed master in chancery (an aide in a court of equity), his first public office, which he held during the Civil War. In 1864 Stevenson was a presidential elector for the Democratic ticket; he was also elected district attorney.

In 1866, he married Letitia Green. They had three daughters and a son, Lewis G. Stevenson. Letitia helped establish the Daughters of the American Revolution as a way of healing the divisions between the North and South after the Civil War, and succeeded the wife of Benjamin Harrison as the DAR's second president-general.

In 1868, at the end of his term as district attorney, he entered law practice with his cousin, James S. Ewing, moving with his wife back to Bloomington, settling in a large house on Franklin Square. Stevenson & Ewing would become one of the state's most prominent law firms. Ewing would later become the U.S. ambassador to Belgium.

The Democratic Party nominated Stevenson for the United States Congress in 1874. Stevenson was well-liked by Republicans and levied influence in the local Masonic lodge. Stevenson also received the nomination of the Independent Reform Party, a state party that fought monopolies following the Panic of 1873.[5] Stevenson campaigned against Republican incumbent John McNulta. He attacked McNulta's support for high tariffs and what became known as the Salary Grab Act, where congressman increased their salaries by 50%. He spoke little of his own positions other than railroad regulation. McNulta attacked back, accusing Stevenson membership in the Knights of the Golden Circle. Thanks to the votes siphoned away from the Republican Base by the Independent Reform Party, Stevenson won the election with 52% of the vote, though he did not carry his hometown of Bloomington. He was elevated to the 44th United States Congress, the first under Democratic control since the Civil War.[6]

In 1876, Stevenson was an unsuccessful candidate for reelection. The Republican presidential ticket, headed by Rutherford B. Hayes carried his district, and Stevenson was narrowly defeated, getting 49.6 percent of the vote. In 1878, he ran on both the Democratic and Greenback tickets and won, returning to a House from which one-third of his earlier colleagues had either voluntarily retired or been removed by the voters. In 1880, again a presidential election year, he once more lost narrowly, and he lost again in 1882 in his final race for Congress. He considered a run in 1884, but a redistricting made his district safely Republican.[7]

In between legislative sessions, Stevenson increased his prominence in Bloomington. He rose to become grandmaster of his Masonic chapter and founded the Bloomington Daily Bulletin in 1881, a Democratic newspaper that sought to challenge the Republican Pantagraph. Stevenson directed the People's Bank and co-managed the McLean County Coal Company with his brothers. The company founded Stevensonville, a company town near the mine shafts. Employees were purportedly fired if they did not support Stevenson in an election year.[8]

Election of Grover Cleveland in 1884 and the U.S. Post Office

The Stevensons vacationed at lake resorts in Wisconsin during summers. There, Stevenson befriended William Freeman Vilas, a growing voice among Midwest Democrats and a friend of Grover Cleveland. Stevenson was a delegate to the 1884 Democratic National Convention, and after briefly supporting a local candidate, he threw his support behind Cleveland. Vilas and Stevenson personally informed Cleveland of the nomination. When Cleveland was elected that November, Vilas was named postmaster general. Although a different supporter was initially named assistant postmaster, Stevenson eventually received the position after the first choice fell ill.[9]

The new position put Stevenson in charge of the largest patronage system in the country. Like his predecessors, Stevenson removed tens of thousands of political opponents from postal positions and replaced them with Democrats. Just before Cleveland left office, he offered Stevenson's name to the Senate Judidiary Committee for appointment to a D.C. federal court, but this was denied. A disappointed Stevenson returned to Bloomington with no political position in 1889.[10]

Vice President, 1893–1897

Cleveland was renominated for President on the first ballot at the 1892 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. At the time, the vice presidency was considered a "final resting place for has-beens and never-wases." Nonetheless, Stevenson's brothers and cousins advocated for his nomination for the position. Likewise, Mayor of Chicago Carter Harrison threw his support behind Stevenson as a native son, believing that he could influence the state to vote Democrat. Stevenson was nominated on the first ballot.[11]

Stevenson backed off his former support of greenbacks in favor of Cleveland's gold standard policy. Unlike Cleveland, who only appeared once in public to support his candidacy, Stevenson traveled with his wife across the county. Cleveland's advisers sent Stevenson to the south to curb the growing appeal of the Populist Party. With his Kentucky roots, Stevenson proved popular at his southern engagements. Stevenson also publicly opposed the Lodge Bill, a proposed bill which would have enfranchised southern blacks.[12] The winning Cleveland-Stevenson ticket carried Illinois, although not Stevenson's home district.

Civil service reformers held out hope for the second Cleveland administration but saw Vice President Stevenson as a symbol of the spoils system. He never hesitated to feed names of Democrats to the Post Office Department. Once he called at the US Treasury Department to protest against an appointment and was shown a letter he had written endorsing the candidate. Stevenson told the treasury officials not to pay attention to any of his written endorsements; if he really favored someone he would tell them personally.

A habitual cigar-smoker, Cleveland developed cancer of the mouth that required immediate surgery in the summer of 1893. The president insisted that the surgery be kept secret to avoid another panic on Wall Street. While on a yacht in New York harbor that summer, Cleveland had his entire upper jaw removed and replaced with an artificial device, an operation that left no outward scar. The cancer surgery remained secret for another quarter century. Cleveland's aides explained that he had merely had dental work. His vice president little realized how close he came to the presidency that summer.

Adlai Stevenson enjoyed his role as vice president, presiding over the U.S. Senate, "the most august legislative assembly known to men." He won praise for ruling in a dignified, nonpartisan manner. In personal appearance he stood six feet tall and was "of fine personal bearing and uniformly courteous to all." Although he was often a guest at the White House, Stevenson admitted that he was less an adviser to the president than "the neighbor to his counsels." He credited the President with being "courteous at all times" but noted that "no guards were necessary to the preservation of his dignity. No one would have thought of undue familiarity." For his part, President Cleveland snorted that the Vice President had surrounded himself with a coterie of free-silver men dubbed the "Stevenson cabinet." The president even mused that the economy had gotten so bad and the Democratic party so divided that "the logical thing for me to do ... was to resign and hand the Executive branch to Mr. Stevenson," joking that he would try to get his friends jobs in Stevenson's new cabinet.

Presidential campaigns of 1896 and 1900

Stevenson was mentioned as a candidate to succeed Cleveland in 1896. Although he chaired the Illinois delegation to the Democratic National Convention, he gained little support. Stevenson, 60 years old, received a smattering of votes, but the convention was taken by storm by a thirty-six-year-old former representative from Nebraska, William Jennings Bryan, who delivered his fiery "Cross of Gold" speech in favor of a free silver plank in the platform. Not only did the Democrats repudiate Cleveland by embracing free silver, but they also nominated Bryan for president. Many Cleveland Democrats, including most Democratic newspapers, refused to support Bryan, but Vice President Stevenson loyally endorsed the ticket.

After the 1896 election, Bryan remained the titular leader of the Democrats and frontrunner for the nomination in 1900. Much of the newspaper speculation about who would run as the party's vice-presidential candidate centered on Indiana Senator Benjamin Shively. When reporter Arthur Wallace Dunn interviewed Shively at the convention, the senator said he "did not want the glory of a defeat as a vice presidential candidate." Disappointed, Dunn said that he still had to file a story on the vice-presidential nomination, and then added: "I believe I'll write a piece about old Uncle Adlai." Shively responded

- That's a good idea. Stevenson is just the man. There you have it. Uniting the old Cleveland element with the new Bryan Democracy. You've got enough for one story. But say, this is more than a joke. Stevenson is just the man.

For the rest of the day, Dunn heard other favorable remarks about Stevenson, and by that night the former vice president was the leading contender, since no one else was "very anxious to be the tail of what they considered was a forlorn hope ticket."

The Populists had already nominated the ticket of Bryan and Charles A. Towne, a pro-silver Republican from Minnesota, with the tacit understanding that Towne would step aside if the Democrats nominated someone else. Bryan preferred his good friend Towne, but Democrats wanted one of their own, and the regular element of the party felt comfortable with Stevenson. Towne withdrew and campaigned for Bryan and Stevenson. As a result, Stevenson, who had run with Cleveland in 1892, now ran in 1900 with Cleveland's opponent Bryan. Twenty-five years senior to Bryan, Stevenson added age and experience to the ticket. Nevertheless, their effort failed badly against the Republican ticket of McKinley and Roosevelt. (Stevenson's role in the race is perhaps more distinguished by his being the first Vice President to win nomination for that office with a different running mate, after having completed his first term. As of 2013, Republican Charles W. Fairbanks's failure to win a second VP term in 1916 is the only example since.)

Final years

After the 1900 election, Stevenson returned again to private practice in Illinois. He made one last attempt at office in a race for governor of Illinois in 1908, at age 73, narrowly losing. In 1909 he was brought in by founder Jesse Grant Chapline to aid distance learning school La Salle Extension University.[13] After that, he retired to Bloomington, where his Republican neighbors described him as "windy but amusing." He died in Chicago on June 14, 1914. His body is interred in a family plot in Evergreen Cemetery, Bloomington, Illinois.

Stevenson's son, Lewis G. Stevenson, was Illinois secretary of state (1914–1917). Stevenson's grandson Adlai Ewing Stevenson II was the Democratic candidate for President of the United States in 1952 and 1956 and Governor of Illinois. His great-grandson, Adlai Ewing Stevenson III, was a U.S. senator from Illinois from 1970 to 1981 and an unsuccessful candidate for Governor of Illinois in 1982 and 1986.

Legacy

In 1962, Stevenson's alma mater, Centre College (which also gave Stevenson an honorary degree in 1893), built and named a residence hall after Stevenson - Stevenson House - as part of a new campus quadrangle.[14]

References

- Specific

- ↑ Baker, Jean H. (1996). The Stevensons: A Biography of An American Family. New York: W. W. Norton & Co. ISBN 0-393-03874-2.

- ↑ Baker 1997, pp. 64–66.

- ↑ Baker 1997, p. 69.

- ↑ Wheeler, Joe (2008). Abraham Lincoln, a Man of Faith and Courage: Stories of Our Most Admired President. p. 53.

- ↑ Baker 1997, p. 117–118.

- ↑ Baker 1997, pp. 121-122.

- ↑ Baker 1997, pp. 126-127.

- ↑ Baker 1997, pp. 127-128.

- ↑ Baker 1997, pp. 129-131.

- ↑ Baker 1997, pp. 131, 132, 143.

- ↑ Baker 1997, pp. 146–147.

- ↑ Baker 1997, pp. 148–150.

- ↑ Staff report (March 2, 1909). Stevenson to Quit Law; Former Vice President Will Aid La Salle Extension University. New York Times

- ↑ http://www.centre.edu/campusbuildings/slideshow_quad/index.html

- General

- Baker, Jean H. (1997). The Stevensons: A Biography of an American Family. New York City: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393315981.

External links

- Works by Adlai Stevenson I at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Adlai Stevenson I at Internet Archive

- Official U.S. Senate biography

- Stevensons put stamp on history, www.pantagraph.com

- Adlai Ewing Stevenson

![]() Media related to Adlai Stevenson I at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Adlai Stevenson I at Wikimedia Commons

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Stevenson, Adlai Ewing". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Stevenson, Adlai Ewing". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Levi P. Morton |

Vice President of the United States March 4, 1893 – March 4, 1897 |

Succeeded by Garret Hobart |

| United States House of Representatives | ||

| Preceded by Thomas F. Tipton |

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Illinois's 13th congressional district March 4, 1879 – March 4, 1881 |

Succeeded by Dietrich C. Smith |

| Preceded by John McNulta |

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Illinois's 13th congressional district March 4, 1875 – March 4, 1877 |

Succeeded by Thomas F. Tipton |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by Arthur Sewall |

Democratic vice presidential nominee 1900 |

Succeeded by Henry G. Davis |

| Preceded by Allen G. Thurman |

Democratic vice presidential nominee 1892 |

Succeeded by Arthur Sewall |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|