Adjoint representation

| Group theory → Lie groups Lie groups |

|---|

|

In mathematics, the adjoint representation (or adjoint action) of a Lie group G is a way of representing the elements of the group as linear transformations of the group's Lie algebra, considered as a vector space. For example, in the case where G is the Lie group of invertible matrices of size n, GL(n), the Lie algebra is the vector space of all (not necessarily invertible) n-by-n matrices. So in this case the adjoint representation is the vector space of n-by-n matrices  , and any element g in GL(n) acts as a linear transformation of this vector space given by conjugation:

, and any element g in GL(n) acts as a linear transformation of this vector space given by conjugation:  .

.

For any Lie group, this natural representation is obtained by linearizing (i.e. taking the differential of) the action of G on itself by conjugation. The adjoint representation can be defined for linear algebraic groups over arbitrary fields.

Definition

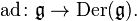

Let G be a Lie group and let  be its Lie algebra (which we identify with TeG, the tangent space to the identity element in G). Define the map

be its Lie algebra (which we identify with TeG, the tangent space to the identity element in G). Define the map

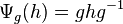

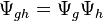

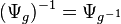

where Aut(G) is the automorphism group of G and the automorphism Ψg is defined by

for all h in G. The differential of Ψg at the identity is an automorphism of the Lie algebra  . We denote this map by Adg:

. We denote this map by Adg:

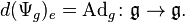

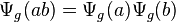

To say that Adg is a Lie algebra automorphism is to say that Adg is a linear transformation of  that preserves the Lie bracket. The map

that preserves the Lie bracket. The map

is called the adjoint representation of G. This is indeed a representation of G since  is a closed[1] Lie subgroup of

is a closed[1] Lie subgroup of  and the above adjoint map is a Lie group homomorphism. Note Ad is a trivial map if G is abelian.

and the above adjoint map is a Lie group homomorphism. Note Ad is a trivial map if G is abelian.

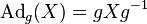

If G is an (immersed) Lie subgroup of the general linear group  , then, since the exponential map is the matrix exponential:

, then, since the exponential map is the matrix exponential:  , taking the derivative of

, taking the derivative of  at t = 0, one gets: for g in G and X in

at t = 0, one gets: for g in G and X in  ,

,

where on the right we have the products of matrices.

Adjoint representation of a Lie algebra

One may always pass from a representation of a Lie group G to a representation of its Lie algebra by taking the derivative at the identity.

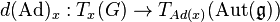

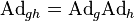

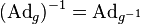

Taking the derivative of the adjoint map

gives the adjoint representation of the Lie algebra  :

:

Here  is the Lie algebra of

is the Lie algebra of  which may be identified with the derivation algebra of

which may be identified with the derivation algebra of  . The adjoint representation of a Lie algebra is related in a fundamental way to the structure of that algebra. In particular, one can show that

. The adjoint representation of a Lie algebra is related in a fundamental way to the structure of that algebra. In particular, one can show that

for all  .[2]

.[2]

Examples

- If G is abelian of dimension n, the adjoint representation of G is the trivial n-dimensional representation.

- If G is a matrix Lie group (i.e. a closed subgroup of GL(n,C)), then its Lie algebra is an algebra of n×n matrices with the commutator for a Lie bracket (i.e. a subalgebra of

). In this case, the adjoint map is given by Adg(x) = gxg−1.

). In this case, the adjoint map is given by Adg(x) = gxg−1. - If G is SL(2, R) (real 2×2 matrices with determinant 1), the Lie algebra of G consists of real 2×2 matrices with trace 0. The representation is equivalent to that given by the action of G by linear substitution on the space of binary (i.e., 2 variable) quadratic forms.

Properties

The following table summarizes the properties of the various maps mentioned in the definition

|

|

| Lie group homomorphism:

|

Lie group automorphism:

|

|

|

| Lie group homomorphism:

|

Lie algebra automorphism:

|

|

|

Lie algebra homomorphism:

|

Lie algebra derivation:

|

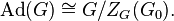

The image of G under the adjoint representation is denoted by Ad(G). If G is connected, the kernel of the adjoint representation coincides with the kernel of Ψ which is just the center of G. Therefore the adjoint representation of a connected Lie group G is faithful if and only if G is centerless. More generally, if G is not connected, then the kernel of the adjoint map is the centralizer of the identity component G0 of G. By the first isomorphism theorem we have

Given a finite-dimensional real Lie algebra  , by Lie's third theorem, there is a connected Lie group

, by Lie's third theorem, there is a connected Lie group  whose Lie algebra is the image of the adjoint representation of

whose Lie algebra is the image of the adjoint representation of  (i.e.,

(i.e.,  .) It is called the adjoint group of

.) It is called the adjoint group of  .

.

Now, if  is the Lie algebra of a connected Lie group G, then

is the Lie algebra of a connected Lie group G, then  is the image of the adjoint representation of G:

is the image of the adjoint representation of G:  .

.

Roots of a semisimple Lie group

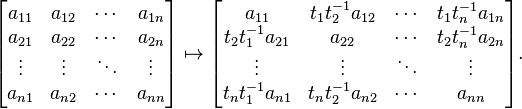

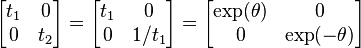

If G is semisimple, the non-zero weights of the adjoint representation form a root system. To see how this works, consider the case G = SL(n, R). We can take the group of diagonal matrices diag(t1, ..., tn) as our maximal torus T. Conjugation by an element of T sends

Thus, T acts trivially on the diagonal part of the Lie algebra of G and with eigenvectors titj−1 on the various off-diagonal entries. The roots of G are the weights diag(t1, ..., tn) → titj−1. This accounts for the standard description of the root system of G = SLn(R) as the set of vectors of the form ei−ej.

Example SL(2, R)

Let us compute the root system for one of the simplest cases of Lie Groups. Let us consider the group SL(2, R) of two dimensional matrices with determinant 1. This consists of the set of matrices of the form:

with a, b, c, d real and ad − bc = 1.

A maximal compact connected abelian Lie subgroup, or maximal torus T, is given by the subset of all matrices of the form

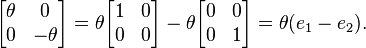

with  . The Lie algebra of the maximal torus is the Cartan subalgebra consisting of the matrices

. The Lie algebra of the maximal torus is the Cartan subalgebra consisting of the matrices

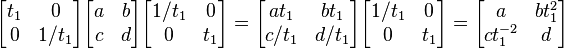

If we conjugate an element of SL(2, R) by an element of the maximal torus we obtain

The matrices

are then 'eigenvectors' of the conjugation operation with eigenvalues  . The function Λ which gives

. The function Λ which gives  is a multiplicative character, or homomorphism from the group's torus to the underlying field R. The function λ giving θ is a weight of the Lie Algebra with weight space given by the span of the matrices.

is a multiplicative character, or homomorphism from the group's torus to the underlying field R. The function λ giving θ is a weight of the Lie Algebra with weight space given by the span of the matrices.

It is satisfying to show the multiplicativity of the character and the linearity of the weight. It can further be proved that the differential of Λ can be used to create a weight. It is also educational to consider the case of SL(3, R).

Variants and analogues

The adjoint representation can also be defined for algebraic groups over any field.

The co-adjoint representation is the contragredient representation of the adjoint representation. Alexandre Kirillov observed that the orbit of any vector in a co-adjoint representation is a symplectic manifold. According to the philosophy in representation theory known as the orbit method (see also the Kirillov character formula), the irreducible representations of a Lie group G should be indexed in some way by its co-adjoint orbits. This relationship is closest in the case of nilpotent Lie groups.

Notes

References

- Fulton, William; Harris, Joe (1991), Representation theory. A first course, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, Readings in Mathematics 129, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-97495-8, MR 1153249, ISBN 978-0-387-97527-6

![\mathrm{ad}_x(y) = [x,y]\,](../I/m/695e8c46394db9258f798a17d3acb108.png)

is linear

is linear

![\mathrm{Ad}_g[x,y] = [\mathrm{Ad}_g x,\mathrm{Ad}_g y]](../I/m/4dc2cab951e308e624f9686f67da4604.png)

is linear

is linear![\mathrm{ad}_{[x,y]} = [\mathrm{ad}_x,\mathrm{ad}_y]](../I/m/ff94d61ee82c534f0bd8ade2adb0f163.png)

is linear

is linear![\mathrm{ad}_x[y,z] = [\mathrm{ad}_x y ,z] + [y,\mathrm{ad}_x z]](../I/m/d3a0ed993cb8f7ff4c362a7dd8554b7a.png)

![\begin{align}

\mathrm{ad}_x(y) & = d (\mathrm{Ad}_{x})_{e}(y) \\

& = \lim_{\varepsilon \to 0}\frac{(I+\varepsilon x)y(I+\varepsilon x)^{-1}-y}{\varepsilon} \\

& = \lim_{\varepsilon \to 0}\frac{(I+\varepsilon x)y(I-\varepsilon x +(\varepsilon x)^2+O(\varepsilon^3))-y}{\varepsilon} \\

& = \lim_{\varepsilon \to 0}\frac{((I+\varepsilon x)yI- (I+\varepsilon x)y\varepsilon x +(I+\varepsilon x)y(\varepsilon x)^2 +O(\varepsilon^3))-y}{\varepsilon} \\

& = \lim_{\varepsilon \to 0}\frac{(I y I+\varepsilon x y I- I y \varepsilon x-\varepsilon x y \varepsilon x +Iy(\varepsilon x)^2+\varepsilon xy(\varepsilon x)^2 +O(\varepsilon^3))-y}{\varepsilon} \\

& = \lim_{\varepsilon \to 0}\frac{y+ x y \varepsilon - y x \varepsilon- x y x \varepsilon^{2} +y x^{2}\varepsilon^2 + x y x^{2}\varepsilon^2 +O(\varepsilon^3) -y}{\varepsilon} \\

& = \lim_{\varepsilon \to 0}x y - y x - x y x \varepsilon +y x^{2}\varepsilon + x y x^{2}\varepsilon +O(\varepsilon^2) \\

& = [x,y]

\end{align}](../I/m/9f33f08ef230293e3855dc00eba8832f.png)