Febrile neutrophilic dermatosis

| Sweet's syndrome | |

|---|---|

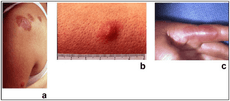

Sweet's syndrome lesions with the classical form of the dermatosis.

| |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | dermatology |

| ICD-10 | L98.2 |

| ICD-9-CM | 695.89 |

| OMIM | 608068 |

| DiseasesDB | 12727 |

| MeSH | D016463 |

Sweet's syndrome (SS), or acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis[1][2] is a skin disease characterized by the sudden onset of fever, an elevated white blood cell count, and tender, red, well-demarcated papules and plaques that show dense infiltrates by neutrophil granulocytes on histologic examination.

The syndrome was first described in 1964 by Dr. Robert Douglas Sweet. It was also known as Gomm-Button disease in honour of the first two patients Dr. Sweet diagnosed with the condition.[3][4][5]

Definition

Sweet, working in Plymouth in 1964, described a disease with four features: fever; leukocytosis; acute, tender, red plaques; and a papillary dermal infiltrate of neutrophils. This led to the name acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Larger series of patients showed that fever and neutrophilia are not consistently present. The diagnosis is based on the two constant features, a typical eruption and the characteristic histologic features; thus the eponym "Sweet's syndrome" is used.

Signs and symptoms

Acute, tender, erythematous plaques, nodes, pseudovesicles and, occasionally, blisters with an annular or arciform pattern occur on the head, neck, legs, and arms, particularly the back of the hands and fingers. The trunk is rarely involved. Fever (50%); arthralgia or arthritis (62%); eye involvement, most frequently conjunctivitis or iridocyclitis (38%); and oral aphthae (13%) are associated features.

Diagnosis

The clinical differential diagnosis includes pyoderma gangrenosum, infection, erythema multiforme, adverse drug reactions, and urticaria. Recurrences are common and affect up to one third of patients.

Laboratory studies

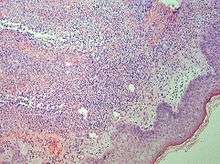

Studies show a moderate neutrophilia (less than 50%), elevated ESR (greater than 30 mm/h) (90%), and a slight increase in alkaline phosphatase (83%). Skin biopsy shows a papillary and mid-dermal mixed infiltrate of polymorphonuclear leukocytes with nuclear fragmentation and histiocytic cells. The infiltrate is predominantly perivascular with endothelial-cell swelling in some vessels, but vasculitic changes (thrombosis; deposition of fibrin, complement, or immunoglobulins within the vessel walls; red blood cell extravasation;inflammatory infiltration of vascular walls) are absent in early lesions.

Perivasculitis occurs secondarily, because of cytokines released by the lesional neutrophils. True transmural vasculitis is not an expected finding histopathologically in SS.

Cause

SS can be classified based upon the clinical setting in which it occurs: classical or idiopathic SS, malignancy-associated SS, and drug-induced SS.[6]

Systemic diseases

SS is a reactive phenomenon and should be considered a cutaneous marker of systemic disease.[6] Careful systemic evaluation is indicated, especially when cutaneous lesions are severe or hematologic values are abnormal. Approximately 20% of cases are associated with malignancy, predominantly hematological, especially acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). An underlying condition (streptococcal infection, inflammatory bowel disease, nonlymphocytic leukemia and other hematologic malignancies, solid tumors, pregnancy) is found in up to 50% of cases. Attacks of SS may precede the hematologic diagnosis by 3 months to 6 years, so that close evaluation of patients in the “idiopathic” group is required.

There is now good evidence that treatment with hematopoietic growth factors — including granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), which is used to treat AML, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor — can cause SS. Lesions typically occur when the patient has leukocytosis and neutrophilia but not when the patient is neutropenic. However, G-CSF may cause SS in neutropenic patients because of the induction of stem cell proliferation, the differentiation of neutrophils, and the prolongation of neutrophil survival.

Associations

Although it may occur in the absence of other known disease, SS is often associated with hematologic disease (including leukemia), and immunologic disease (rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, behçet's syndrome).

A genetic association has been suggested,[7] but no specific genetic link has been identified.

Treatment

Systemic corticosteroids such as (prednisone) can produce rapid improvement and are the “gold standard” for treatment. The temperature, white blood cell count, and eruption improve within 72 hours. The skin lesions clear within 3 to 9 days. Abnormal laboratory values rapidly return to normal. There are, however, frequent recurrences. Corticosteroids are tapered within 2 to 6 weeks to zero.

Resolution of the eruption is occasionally followed by milia and scarring. The disease clears spontaneously in some patients. Topical and/or intralesional corticosteroids may be effective as either monotherapy or adjuvant therapy. Oral potassium iodide or colchicine may induce rapid resolution.

Patients who have a potential systemic infection or in whom corticosteroids are contraindicated can use these agents as a first-line therapy. In one study, indomethacin, 150 mg per day, was given for the first week, and 100 mg per day was given for 2 additional weeks. Seventeen of 18 patients had a good initial response; fever and arthralgias were markedly attenuated within 48 hours, and eruptions cleared between 7 and 14 days.

Patients whose cutaneous lesions continued to develop were successfully treated with prednisone (1 mg/kg per day). No patient had a relapse after discontinuation of indomethacin. Other alternatives to corticosteroid treatment include dapsone, doxycycline, clofazimine, and cyclosporine. All of these drugs influence migration and other functions of neutrophils.

See also

- Chloroma

- List of cutaneous conditions

- Periodic fever syndrome - also known as autoinflammatory diseases or autoinflammatory syndromes.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. |

- ↑ Mustafa NM, Lavizzo M (2008). "Sweet's syndrome in a patient with Crohn's disease: a case report". J Med Case Reports 2: 221. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-2-221. PMC 2503996. PMID 18588703.

- ↑ James, W; Berger, T; Elston D (2005). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology (10th ed.). Saunders. p. 145. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- ↑ synd/3019 at Who Named It?

- ↑ Sweet RD (1964). "An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis". Br. J. Dermatol. 76: 349–56. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1964.tb14541.x. PMID 14201182.

- ↑ Cohen, Phillip R (2007). "Sweet's syndrome - a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 2 (34). doi:10.1186/1750-1172-2-34. PMC 1963326. PMID 17655751. Retrieved 4 Jan 2011.

- 1 2 Cohen PR (2007). "Sweet's syndrome--a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis". Orphanet J Rare Dis 2: 34. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-2-34. PMC 1963326. PMID 17655751.

- ↑ Parsapour K, Reep MD, Gohar K, Shah V, Church A, Shwayder TA (July 2003). "Familial Sweet's syndrome in 2 brothers, both seen in the first 2 weeks of life". J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 49 (1): 132–8. doi:10.1067/mjd.2003.328. PMID 12833027.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

External links

- Autoinflammatory Alliance

- Autoinflammatory Alliance - CANDLE Syndrome

- Autoinflammatory Alliance - Disease Comparison Chart (includes Sweet's syndrome)

- Autoinflammatory Alliance - Majeed Syndrome

- DermNet NZ - Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis or Sweet syndrome

- Sweet's Syndrome UK