Actuarial notation

1. An upper case A is an assurance paying 1 on the insured event; Lower case a is an annuity paying 1 per annum at the appropriate time

2. Bar implies continuous - or paid at the moment of death; double dot - implies paid at the beginning of the year; no mark implies paid at the end of the year

3. for

-year old person, for

-year old person, for  years

years4. paid if

dies within

dies within  years

years 5. deferred (

years)

years)6. no fixed meaning, but often double force of interest

Actuarial notation is a shorthand method to allow actuaries to record mathematical formulas that deal with interest rates and life tables.

Traditional notation uses a halo system where symbols are placed as superscript or subscript before or after the main letter. Example notation using the halo system can be seen below.

Various proposals have been made to adopt a linear system where all the notation would be on a single line without the use of superscripts or subscripts. Such a method would be useful for computing where representation of the halo system can be extremely difficult. However, a standard linear system has yet to emerge.

Example notation

Interest rates

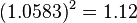

is the annual effective interest rate, which is the "true" rate of interest over a year. Thus if the annual interest rate is 12% then

is the annual effective interest rate, which is the "true" rate of interest over a year. Thus if the annual interest rate is 12% then  .

.

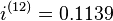

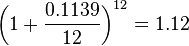

is the nominal interest rate convertible

is the nominal interest rate convertible  times a year, and is numerically equal to

times a year, and is numerically equal to  times the effective rate of interest over one

times the effective rate of interest over one  th of a year. For example,

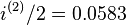

th of a year. For example,  is the nominal rate of interest convertible semiannually. If the effective annual rate of interest is 12%, then

is the nominal rate of interest convertible semiannually. If the effective annual rate of interest is 12%, then  represents the effective interest rate every six months. Since

represents the effective interest rate every six months. Since  , we have

, we have  and hence

and hence  . The "(m)" appearing in the symbol

. The "(m)" appearing in the symbol  is not an "exponent." It merely represents the number of interest conversions, or compounding times, per year. Semi-annual compounding, (or converting interest every six months), is frequently used in valuing bonds (see also fixed income securities) and similar monetary financial liability instruments, whereas home mortgages frequently convert interest monthly. Following the above example again where

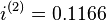

is not an "exponent." It merely represents the number of interest conversions, or compounding times, per year. Semi-annual compounding, (or converting interest every six months), is frequently used in valuing bonds (see also fixed income securities) and similar monetary financial liability instruments, whereas home mortgages frequently convert interest monthly. Following the above example again where  , we have

, we have  since

since  .

.

Effective and nominal rates of interest are not the same because interest paid in earlier measurement periods "earns" interest in later measurement periods; this is called compound interest. That is, nominal rates of interest credit interest to an investor, (alternatively charge, or debit, interest to a debtor), more frequently than do effective rates. The result is more frequent compounding of interest income to the investor, (or interest expense to the debtor), when nominal rates are used.

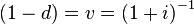

The symbol  represents the present value of 1 to be paid one year from now:

represents the present value of 1 to be paid one year from now:

This present value factor, or discount factor, is used to determine the amount of money that must be invested now in order to have a given amount of money in the future. For example, if you need 1 in one year, then the amount of money you should invest now is:  . If you need 25 in 5 years the amount of money you should invest now is:

. If you need 25 in 5 years the amount of money you should invest now is:  .

.

is the annual effective discount rate:

is the annual effective discount rate:

The value of  can also be calculated from the following relationships:

can also be calculated from the following relationships:  The rate of discount equals the amount of interest earned during a one-year period, divided by the balance of money at the end of that period. By contrast, an annual effective rate of interest is calculated by dividing the amount of interest earned during a one-year period by the balance of money at the beginning of the year. The present value (today) of a payment of 1 that is to be made

The rate of discount equals the amount of interest earned during a one-year period, divided by the balance of money at the end of that period. By contrast, an annual effective rate of interest is calculated by dividing the amount of interest earned during a one-year period by the balance of money at the beginning of the year. The present value (today) of a payment of 1 that is to be made  years in the future is

years in the future is  . This is analogous to the formula

. This is analogous to the formula  for the future (or accumulated) value

for the future (or accumulated) value  years in the future of an amount of 1 invested today.

years in the future of an amount of 1 invested today.

, the nominal rate of discount convertible

, the nominal rate of discount convertible  times a year, is analogous to

times a year, is analogous to  . Discount is converted on an

. Discount is converted on an  th-ly basis.

th-ly basis.

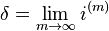

, the force of interest, is the limiting value of the nominal rate of interest when

, the force of interest, is the limiting value of the nominal rate of interest when  increases without bound:

increases without bound:

In this case, interest is convertible continuously.

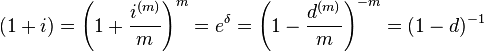

The general relationship between  ,

,  and

and  is:

is:

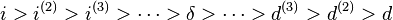

Their numerical value can be compared as follows:

Life tables

A life table (or a mortality table) is a mathematical construction that shows the number of people alive (based on the assumptions used to build the table) at a given age. In addition to the number of lives remaining at each age, a mortality table typically provides various probabilities associated with the development of these values.

is the number of people alive, relative to an original cohort, at age

is the number of people alive, relative to an original cohort, at age  . As age increases the number of people alive decreases.

. As age increases the number of people alive decreases.

is the starting point for

is the starting point for  : the number of people alive at age 0. This is known as the radix of the table. Some mortality tables begin at an age greater than 0, in which case the radix is the number of people assumed to be alive at the youngest age in the table.

: the number of people alive at age 0. This is known as the radix of the table. Some mortality tables begin at an age greater than 0, in which case the radix is the number of people assumed to be alive at the youngest age in the table.

is the limiting age of the mortality tables.

is the limiting age of the mortality tables.  is zero for all

is zero for all  .

.

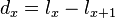

is the number of people who die between age

is the number of people who die between age  and age

and age  .

.  may be calculated using the formula

may be calculated using the formula

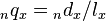

is the probability of death between the ages of

is the probability of death between the ages of  and age

and age  .

.

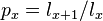

is the probability that a life age

is the probability that a life age  will survive to age

will survive to age  .

.

Since the only possible alternatives from one age ( ) to the next (

) to the next ( ) are living and dying, the relationship between these two probabilities is:

) are living and dying, the relationship between these two probabilities is:

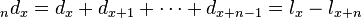

These symbols may also be extended to multiple years, by inserting the number of years at the bottom left of the basic symbol.

shows the number of people who die between age

shows the number of people who die between age  and age

and age  .

.

is the probability of death between the ages of

is the probability of death between the ages of  and age

and age  .

.

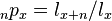

is the probability that a life age

is the probability that a life age  will survive to age

will survive to age  .

.

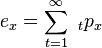

Another statistic that can be obtained from a life table is life expectancy.

is the curtate expectation of life for a person alive at age

is the curtate expectation of life for a person alive at age  . This is the expected number of complete years remaining to live (you may think of it as the expected number of birthdays that the person will celebrate).

. This is the expected number of complete years remaining to live (you may think of it as the expected number of birthdays that the person will celebrate).

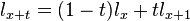

A life table generally shows the number of people alive at integral ages. If we need information regarding a fraction of a year, we must make assumptions with respect to the table, if not already implied by a mathematical formula underlying the table. A common assumption is that of a Uniform Distribution of Deaths (UDD) at each year of age. Under this assumption,  is a linear interpolation between

is a linear interpolation between  and

and  . i.e.

. i.e.

Annuities

The basic symbol for the present value of an annuity is  . The following notation can then be added:

. The following notation can then be added:

- Notation to the top-right indicates the frequency of payment (i.e., the number of annuity payments that will be made during each year). A lack of such notation means that payments are made annually.

- Notation to the bottom-right indicates the age of the person when the annuity starts and the period for which an annuity is paid.

- Notation directly above the basic symbol indicates when payments are made. Two dots indicates an annuity whose payments are made at the beginning of each year (an "annuity-due"); a horizontal line above the symbol indicates an annuity payable continuously (a "continuous annuity"); no mark above the basic symbol indicates an annuity whose payments are made at the end of each year (an "annuity-immediate").

If the payments to be made under an annuity are independent of any life event, it is known as an annuity-certain. Otherwise, in particular if payments end upon the beneficiary's death, it is called a life annuity.

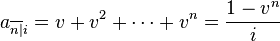

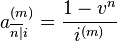

(read a-angle-n at i) represents the present value of an annuity-immediate, which is a series of unit payments at the end of each year for

(read a-angle-n at i) represents the present value of an annuity-immediate, which is a series of unit payments at the end of each year for  years (in other words: the value one period before the first of n payments). This value is obtained from:

years (in other words: the value one period before the first of n payments). This value is obtained from:

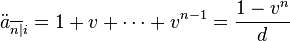

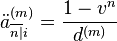

represents the present value of an annuity-due, which is a series of unit payments at the beginning of each year for

represents the present value of an annuity-due, which is a series of unit payments at the beginning of each year for  years (in other words: the value at the time of the first of n payments). This value is obtained from:

years (in other words: the value at the time of the first of n payments). This value is obtained from:

is the value at the time of the last payment,

is the value at the time of the last payment,  the value one period later.

the value one period later.

If the symbol  is added to the top-right corner, it represents the present value of an annuity whose payments occur each one

is added to the top-right corner, it represents the present value of an annuity whose payments occur each one  th of a year for a period of

th of a year for a period of  years, and each payment is one

years, and each payment is one  th of a unit.

th of a unit.

,

,

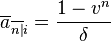

is the limiting value of

is the limiting value of  when

when  increases without bound. The underlying annuity is known as a continuous annuity.

increases without bound. The underlying annuity is known as a continuous annuity.

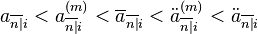

The present values of these annuities may be compared as follows:

To understand the relationships shown above, consider that cash flows paid at a later time have a smaller present value than cash flows of the same total amount that are paid at earlier times.

- The subscript

which represents the rate of interest may be replaced by

which represents the rate of interest may be replaced by  or

or  , and is often omitted if the rate is clearly known from the context.

, and is often omitted if the rate is clearly known from the context. - When using these symbols, the rate of interest is not necessarily constant throughout the lifetime of the annuities. However, when the rate varies, the above formulas will no longer be valid; particular formulas can be developed for particular movements of the rate.

Life annuities

A life annuity is an annuity whose payments are contingent on the continuing life of the annuitant. The age of the annuitant is an important consideration in calculating the actuarial present value of an annuity.

- The age of the annuitant is placed at the bottom right of the symbol, without an "angle" mark.

For example:

indicates an annuity of 1 unit per year payable at the end of each year until death to someone currently age 65

indicates an annuity of 1 unit per year payable at the end of each year until death to someone currently age 65

indicates an annuity of 1 unit per year payable for 10 years with payments being made at the end of each year

indicates an annuity of 1 unit per year payable for 10 years with payments being made at the end of each year

indicates an annuity of 1 unit per year for 10 years, or until death if earlier, to someone currently age 65

indicates an annuity of 1 unit per year for 10 years, or until death if earlier, to someone currently age 65

indicates an annuity of 1 unit per year payable 12 times a year (1/12 unit per month) until death to someone currently age 65

indicates an annuity of 1 unit per year payable 12 times a year (1/12 unit per month) until death to someone currently age 65

indicates an annuity of 1 unit per year payable at the start of each year until death to someone currently age 65

indicates an annuity of 1 unit per year payable at the start of each year until death to someone currently age 65

or in general:

, where

, where  is the age of the annuitant,

is the age of the annuitant,  is the number of years of payments (or until death if earlier),

is the number of years of payments (or until death if earlier),  is the number of payments per year, and

is the number of payments per year, and  is the interest rate.

is the interest rate.

In the interest of simplicity the notation is limited and does not, for example, show whether the annuity is payable to a man or a woman (a fact that would typically be determined from the context, including whether the life table is based on male or female mortality rates).

The Actuarial Present Value of life contingent payments can be treated as the mathematical expectation of a present value random variable, or calculated through the current payment form.

Life insurance

The basic symbol for a life insurance is  . The following notation can then be added:

. The following notation can then be added:

- Notation to the top-right indicates the timing of the payment of a death benefit. A lack of notation means payments are made at the end of the year of death. A figure in parenthesis (for example

) means the benefit is payable at the end of the period indicated (12 for monthly; 4 for quarterly; 2 for semi-annually; 365 for daily).

) means the benefit is payable at the end of the period indicated (12 for monthly; 4 for quarterly; 2 for semi-annually; 365 for daily). - Notation to the bottom-right indicates the age of the person when the life insurance begins.

- Notation directly above the basic symbol indicates the "type" of life insurance, whether payable at the end of the period or immediately. A horizontal line indicates life insurance payable immediately, whilst no mark above the symbol indicates payment is to be made at the end of the period indicated.

For example:

indicates a life insurance benefit of 1 payable at the end of the year of death.

indicates a life insurance benefit of 1 payable at the end of the year of death.

indicates a life insurance benefit of 1 payable at the end of the month of death.

indicates a life insurance benefit of 1 payable at the end of the month of death.

indicates a life insurance benefit of 1 payable at the (mathematical) instant of death.

indicates a life insurance benefit of 1 payable at the (mathematical) instant of death.

Force of mortality

Among actuaries, force of mortality refers to what economists and other social scientists call the hazard rate and is construed as an instantaneous rate of mortality at a certain age measured on an annualized basis.

In a life table, we consider the probability of a person dying between age (x) and age x + 1; this probability is called qx. In the continuous case, we could also consider the conditional probability that a person who has attained age (x) will die between age (x) and age (x + Δx) as:

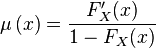

where FX(x) is the cumulative distribution function of the continuous age-at-death random variable, X. As Δx tends to zero, so does this probability in the continuous case. The approximate force of mortality is this probability divided by Δx. If we let Δx tend to zero, we get the function for force of mortality, denoted as μ(x):

See also

- Actuary

- Actuarial present value

- Actuarial science

- Annual percentage rate

- Interest

- Life table

- Life Insurance

- Mathematics of finance