Acting President of the United States

Acting President of the United States is a reference to a person who legitimately exercises presidential powers even though that person does not hold the office of the President of the United States in his own right.

Origin of the position: Constitution (1787)

Article II, section 1 of the Constitution, appears to establish the position of acting President:

In case of the Removal of the President from office, or of his Death, Resignation, or Inability to discharge the Powers and Duties of the said Office, the Same shall devolve on the Vice President, and the Congress may by Law provide for the Case of Removal, Death, Resignation or Inability, both of the President and Vice President, declaring what Officer shall then act as President, and such Officer shall act accordingly, until the Disability be removed, or a President shall be elected. (Emphasis added.)

Article I, section 3 of the Constitution, providing for the election of officers of the Senate, appears to assume that the Vice President succeeds to the Office of the President rather than merely discharging the duties thereof:

The Vice President of the United States shall be President of the Senate, but shall have no Vote, unless they be equally divided.The Senate shall choose their other Officers, and also a President pro tempore, in the Absence of the Vice President, or when he shall exercise the Office of President of the United States. (Emphasis added.)

Questions raised

The above texts raised many questions regarding the status of a Vice President upon the death or resignation of the elected President, and whether he would be an "Acting President," which raised the following questions:

- Did the phrase "the same shall devolve upon the Vice President" refer to the office of President or simply its powers and responsibilities? If it meant the office, then a disabled President had no legal method of returning to power.

- What specific conditions would install the Vice President (or another officer) as Acting President? What was the procedure necessary to declare the incapacity of the President? Would Congressional action be necessary to declare a President disabled, or could he declare himself incapacitated?

- What exception can there be restricting the President to return to office after an "acting President" is appointed?

Presidential succession precedent

Since a strict adherence to either of the two sections of the Constitution could yield opposing interpretations, there was, naturally, much disagreement when the matter was first put to the test. Any question regarding the Vice President succeeding to the Presidency was for all intents and purposes resolved in April 1841 when John Tyler succeeded William Henry Harrison upon Harrison's death. Tyler made it clear that he was the President rather than the Vice President acting as such, thus establishing precedent in accordance with the Article I interpretation. Constitutional scholars, while not generally criticizing Tyler's actions, nonetheless were uncomfortable with the informality of this process and could easily imagine problematic situations in which the applicability of the precedent would not be clear. This question would come up repeatedly over the next 100 years until resolved by the ratification of the Twenty-fifth Amendment in 1967.

Presidential disability before 1967

The possibility of installing an acting President was informally discussed several times prior to the ratification of the 25th Amendment, but in nearly every case the Vice President (or the next in the line of succession) did not act, most likely because there was no formal process established for doing so.

Some constitutional scholars believe that Tyler's actions in succeeding Harrison as President directly conflicted with the provisions of the Twelfth Amendment, adopted in 1804, which reads in part:

And if the House of Representatives shall not choose a President whenever the right of choice shall devolve upon them, before the fourth day of March next following, then the Vice-President shall act as President, as in case of the death or other constitutional disability of the President. (Emphasis added.)

This clause proved vague, in that it was unclear what qualified as a "constitutional disability". The amendment is describing Presidential elections, and the duty of the House of Representatives in choosing a President when the Electoral College is deadlocked. The clause assumes a Vice Presidential candidate has cleared all electoral hurdles and can carry out the duties of the President until the House can select a full-term President per its Constitutional requirements. Because someone presumably could claim constitutional priority to the presidency over the Vice President in this scenario, the Vice President logically could not assume the full Presidency. "Constitutional disability" in this context could describe either the potential President's failure to meet the eligibility requirements of the office or his not having completed his electoral affirmation by Congress.

Because President Harrison was dead, Tyler could not lose his constitutional authority to act as President other than through his own death or incapacity, and therefore the assumption of the full title of President was simply a matter of semantics. When the Twentieth Amendment was ratified in 1933, Section 3 superseded the above-quoted portion of the Twelfth Amendment but did nothing to clarify what qualified as a "constitutional disability":

If, at the time fixed for the beginning of the term of the President, the President elect shall have died, the Vice President elect shall become President. If a President shall not have been chosen before the time fixed for the beginning of his term, or if the President elect shall have failed to qualify, then the Vice President elect shall act as President until a President shall have qualified; and the Congress may by law provide for the case wherein neither a President elect nor a Vice President shall have qualified, declaring who shall then act as President, or the manner in which one who is to act shall be selected, and such person shall act accordingly until a President or Vice President shall have qualified.

The amendments' provisions remained untested in over a dozen instances in which a President's health or other considerations might have made it prudent to have the Vice President act as President, including these:[1]

- During May 1790, when President George Washington was temporarily debilitated by severe influenza. Many thought Washington would die but neither he nor Vice President John Adams or the Senate attempted to invoke any effort to install Adams as Acting President because there was no provision for such action.

- For several weeks in 1813, when President James Madison suffered from a high fever and delirium. During this time some believed that he had become deranged and could not carry out his responsibilities, which was especially troublesome in the midst of the War of 1812. Despite the intensive military operations, apparently no serious thought was given to stripping Madison of his powers and duties temporarily, perhaps partly because his Vice President, Elbridge Gerry, was also in poor health and nearing age 70.

- During early 1818, when President James Monroe was temporarily incapacitated with malaria. Monroe recovered, and transferring power to Vice President Daniel D. Tompkins was never considered.

- On March 4, 1849, President-elect Zachary Taylor was to be inaugurated, but he refused because it was a Sunday and he wished to not break the Sabbath. Because of this, some have argued that neither Taylor nor his Vice President Millard Fillmore had any legal authority as President. They go on to argue that, because the previous President's term had expired at noon, President pro tempore of the Senate David Rice Atchison was Acting President for the day. Historians, biographers and Constitutional scholars heavily dispute both claims.[2]

- During the 1868 impeachment trial of President Andrew Johnson. Though he was ultimately acquitted, some argue he should not have been permitted to exercise his constitutional authorities during the trial. With the Vice Presidency vacant during the trial, the person next in line was Senate President pro tempore Benjamin Franklin Wade. Because Wade was one of those who sat in judgment of Johnson, a declaration of disability could have been seen as akin to an outright coup d'état by Congress, and consequently was never considered.

- During the summer of 1881, after the July 2 shooting of President James A. Garfield by Charles J. Guiteau. Though Garfield lived 80 days after the shooting, he spent most of this time heavily sedated and was incapable of discharging presidential duties. Despite a widespread belief that Vice President Chester A. Arthur was a puppet of the Stalwart factions of the Republican Party, and particularly New York Senator Roscoe Conkling, Garfield's cabinet at least informally discussed scenarios under which Arthur could act as President. Again, however, there being no apparatus in place and no precedent, nothing became of it.

- In 1884–1885, when Garfield's successor, Chester A. Arthur, was suffering the effects of the Bright's disease that would take his life less than two years after he left office. As had been the case with Andrew Johnson before him, there was no Vice President in place to succeed him, and no procedure for allowing anyone to act as President if Arthur had become totally disabled.

- On June 13 and July 17, 1893, respectively, when President Grover Cleveland underwent two operations to remove and repair damage from a cancerous tumor from his upper jaw. The operation was kept secret until 1918, well after Cleveland's death. Any plans related to his potential long-term disability, if there were any, were not documented.

- During September 1901, after Leon Czolgosz's shooting, on the 6th, in Buffalo, New York, of President William McKinley. Vice President Theodore Roosevelt was summoned to Buffalo, but no action was taken to permit him to discharge McKinley's duties during his final days.

- During May 1909, when President William Howard Taft simultaneously had influenza and suffered a family tragedy (his wife had suffered a stroke).

- When President Woodrow Wilson suffered a slight stroke on September 25, 1919. On October 2, he had a massive stroke, which left him partly paralyzed and completely incapacitated. Rather than transfer Presidential authority to Vice President Thomas R. Marshall, Wilson's condition was hidden (to the extent that he was physically isolated) from the Vice President, the Cabinet, Congress, and the public for most of the remainder of his second term. Many believe that First Lady Edith Bolling Galt Wilson was the de facto President, because she controlled access to Wilson and spoke on his behalf.[3]

- From late 1943 until President Franklin D. Roosevelt's death on April 12, 1945. Roosevelt reportedly suffered from various life-threatening ailments, including malignant melanoma, hypertensive cardiomyopathy, severe high blood pressure, congestive heart failure, and stroke-related symptoms (to which he eventually succumbed). Henry A. Wallace, his Vice President for most of this period, was largely regarded by many governmental and Democratic insiders as too close to the Soviet Union and potentially a Communist sympathizer, so that moving him into any sort of Acting Presidency or co-Presidency was never seriously considered. Also, it was considered necessary for national security during World War II not to show weakness to America's enemies. When Harry S. Truman became Vice President in January 1945, he also was kept unaware of Roosevelt's condition.

- During the midpoint of Dwight D. Eisenhower's presidency, there were three instances in which the President was disabled. The first occurred in September 1955, when Eisenhower suffered a heart attack while on vacation. On June 8, 1956, he was hospitalized for a bowel obstruction that ultimately required surgery and incapacitated him for six days. On November 25, 1957, Eisenhower suffered a mild stroke, which caused him to be hospitalized for three days. In each case, Vice President Richard Nixon did carry out some of Eisenhower's informal presidential responsibilities, but full presidential authority (such as signing bills into law, for example) remained solely with Eisenhower.

- In 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson had a gallbladder operation. During the surgery and recovery, there was no move to have Vice President Hubert Humphrey assume presidential powers and duties.

Twenty-fifth Amendment

The Twenty-fifth Amendment, ratified in 1967, clears up many of the issues which surrounded presidential succession and incapacity. Section 1 made it clear that in the event of a vacancy in the office of President, the Vice President succeeds to the office, while Section 2 established a procedure for filling Vice Presidential vacancies.

Pertinent text of the amendment

Section 3.Whenever the President transmits to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives his written declaration that he is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, and until he transmits to them a written declaration to the contrary, such powers and duties shall be discharged by the Vice President as Acting President.

Section 4. Whenever the Vice President and a majority of either the principal officers of the executive departments or of such other body as Congress may by law provide, transmit to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives their written declaration that the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, the Vice President shall immediately assume the powers and duties of the office as Acting President.

Thereafter, when the President transmits to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives his written declaration that no inability exists, he shall resume the powers and duties of his office unless the Vice President and a majority of either the principal officers of the executive department or of such other body as Congress may by law provide, transmit within four days to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives their written declaration that the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office. Thereupon Congress shall decide the issue, assembling within forty-eight hours for that purpose if not in session. If the Congress, within twenty-one days after receipt of the latter written declaration, or, if Congress is not in session, within twenty-one days after Congress is required to assemble, determines by two-thirds vote of both Houses that the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, the Vice President shall continue to discharge the same as Acting President; otherwise, the President shall resume the powers and duties of his office.

Self-declared incapacity

Section 3 of the amendment set forth a procedure whereby a President who believes he will be temporarily unable to perform the duties of his office may declare himself "unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office." Upon this declaration, which is transmitted in writing to the Speaker of the House of Representatives and the President pro tempore of the Senate, the Vice President becomes Acting President. The Vice President continues to act as President until the President declares, by another letter to the leaders of each house of Congress, that he is once again able to discharge the powers and duties of the presidency.

Incapacity declared by Vice President and cabinet

Section 4 of the amendment sets forth a second procedure establishing presidential incapacity. This second method allows the Vice President, together with a majority of the members of the Cabinet ("the principal officers of the executive departments"), to declare the President disabled.

The not-self-declared incapacity provision established by Section 4 of the Twenty-fifth Amendment requires action by "the Vice President and a majority of either the principal officers of the executive departments or of such other body as Congress may by law provide". Therefore, the text of the Twenty-fifth Amendment allows Congress to transfer, by law, the role of the Cabinet to another body. In that case, instead of actions taken by the Vice President and a majority of the Cabinet, the procedures under Section 4 of the Twenty-fifth Amendment would require action by the Vice President together with a majority of the other body provided by law. However, Congress has not passed a statute transferring to another body the role of the "principal officers of the executive departments" in determining presidential incapacity, and therefore that role is vested in the Cabinet.

When the declaration certifying the President's incapacity, signed by the Vice President and by a majority of the members of the Cabinet, is transmitted in writing to the Speaker of the House of Representatives and to the President pro tempore of the Senate, the Vice President immediately becomes Acting President.

If the President submits a letter to the leaders of Congress stating that he is able to discharge the powers and duties of the presidency and four days elapse without further action on the part of the Vice President and a majority of the Cabinet, then the Vice President's service as acting president is terminated. Thus, unlike the procedure under Section 3 of the amendment, a declaration by the incapacitated President to the effect that he is able to resume the powers and duties of his office does not have immediate effect if the incapacity was declared under section 4 of the amendment. The President only resumes his powers and duties if the Vice President and a majority of the Cabinet do not recertify the President's incapacity within the constitutionally prescribed four-day period. If the Vice President and a majority of the Cabinet recertify that declaration to the leaders of Congress, the Vice President remains in his role as Acting President and Congress is constitutionally obligated to consider (or to assemble within 48 hours and consider, if not already in session) the issue. The Congress has a maximum of 21 days after receipt of the Vice President and Cabinet's most recent letter to decide if the President is indeed not able to discharge the powers and duties of his office. If Congress does not, by two-thirds vote of each house, determine, within the mandated 21 day period, that the President is indeed unable to discharge the powers and duties his office, then those duties automatically return to the President and the Vice President's service as Acting President ends.

From the text of Section 4 of the Twenty-fifth Amendment, it is not clear whether or not the Vice President and a majority of the Cabinet can recognize and declare by themselves that the President's incapacity has ceased, provoking the immediate cessation of the Vice President's service as Acting President and the immediate return of the powers and duties of the presidency to the President. The amendment mentions only a letter by the President himself, stating that he is now able to resume his powers and duties, and it requires the President to wait for four days for a possible re-certification of the incapacity by the Vice President and Cabinet, so that the President's letter only has the effect of returning to him the powers and duties of the office after those four days elapse. The amendment is silent about the possibility of the Vice President (then discharging the role of Acting President) and a majority of the Cabinet formally declaring to the Speaker of the House of Representatives and to the President pro tempore of the Senate that they agree that the reason for the section 4 declaration of incapacity has ceased, so that the President can resume the powers and duties of his office at once.

Ostensibly to be used in the event of a President's complete mental or physical disability, this method of transferring presidential power has never been used.

Succession beyond the Vice President

In a preliminary draft of what ultimately became the Twenty-fifth Amendment, the line of presidential succession was spelled out in great detail, consisting solely of the existing cabinet officers and allowing for addition of future cabinet positions.

Realizing that committing such a list to the Constitution could cause issues later should amending the line of succession be desirable, however, led Congress to deliver an amendment which did not name specific officers to succeed the President.

Action by others as president under the Presidential Succession Act

Congress, acting under the powers conferred upon it by Article II, Section 1 of the United States Constitution, and by Section 3 of the Twentieth Amendment, has provided for cases where neither a President nor Vice President is able to discharge the powers and duties of the office of President via the Presidential Succession Act (officially styled "An Act to provide for the performance of the duties of the office of President in case of the removal, resignation, death, or inability both of the President and Vice President").

The constitutional delegation of authority that enabled Congress to enact the Presidential Succession Act is twofold: the authority of Congress to regulate cases when neither a President elect, nor a Vice President elect have qualified, determining who shall act as President in that specific situation stems from Section 3 of the Twentieth Amendment. On the other hand, the power of Congress to determine who shall act as President in the cases of removal, resignation, death, or inability both of the President and Vice President is provided for in article Article II, Section 1, Clause 6, of the Constitution. Congress has chosen to regulate both situations by the same statute, and the Presidential Succession Act passed in 1947 deals with both cases.

Presidential Succession Act of 1947 is not the first statute to have been enacted by Congress under the above-mentioned constitutional provisions. Before the enactment of the current statute, previous Acts of Congress (the Presidential Succession Acts of 1792 and 1886) dealt with the hypothesis of there being neither a President nor a Vice President able to discharge the powers of the presidency.

Apart from the circumstances regulated by sections 3 and 4 of the Twenty-fifth Amendment, the provisions of the Presidential Succession Act of 1947 regulate the only other scenarios in which there would be an Acting President.

While none of these officers would succeed to the presidency as would a Vice President, the provisions of the Presidential Succession Act of 1947, now codified in Title 3, Chapter 1, section 19 of the United States Code, create a line of succession that allows the Speaker of the House, the President pro tempore of the Senate, and Cabinet officers, to serve as Acting President in the case of removal, resignation, death or inability of both the President and Vice President, and also in the case of failure to qualify of both a President elect and a Vice President elect. The following is the currently established line of succession after the President and the Vice President:

- Speaker of the House of Representatives

- President pro tempore of the Senate

- Secretary of State

- Secretary of the Treasury

- Secretary of Defense

- Attorney General

- Secretary of the Interior

- Secretary of Agriculture

- Secretary of Commerce

- Secretary of Labor

- Secretary of Health and Human Services

- Secretary of Housing and Urban Development

- Secretary of Transportation

- Secretary of Energy

- Secretary of Education

- Secretary of Veterans Affairs

- Secretary of Homeland Security

The fact that Section 2 of the 25th Amendment allows a President to nominate a new Vice President whenever a vacancy occurs in that office, while not directly impacting the Presidential Succession Act, has greatly diminished the potential for the Act coming into operation. Indeed, since the office of Vice President, once vacant, no longer remains vacant until the end of the presidential term, but is now filled by presidential nomination confirmed by Congress, the likelihood of there ever being a time when there is simultaneously neither a President nor a Vice President able to discharge the powers and duties of the presidency has greatly decreased.

Designated survivor

The practice of naming a designated survivor originated during the Cold War amid fears of a nuclear attack. Only Cabinet members who are eligible to succeed to the presidency (i.e., natural-born citizen over the age of 35, and has lived in the United States for at least 14 years; additionally, the cabinet officer must have not been convicted by the Senate, and not have participated in a rebellion against the United States.) are chosen as designated survivors. For example, Secretary of State Madeleine Albright was not a natural-born citizen (having immigrated to the United States at age 9 from Czechoslovakia), and was thus skipped in the official line of presidential succession. The designated survivor is provided presidential-level security and transport for the duration of the event. An aide carries the nuclear football with them. However, they are not given a briefing on what to do in the event that the other successors to the presidency are killed.[4]

Since 2005, members of Congress have also served as designated survivors. In addition to serving as a rump legislature in the event that all of their colleagues were killed, a surviving Representative and Senator could ascend to the offices of Speaker of the House and President Pro Tempore of the Senate, offices which immediately follow the Vice President in the line of succession. If such a legislative survivor were the sitting Speaker or President Pro Tempore – as for the 2005, 2006, and 2007 State of the Union addresses, in which President Pro Tempore Ted Stevens (R-Alaska) or Sen. Robert Byrd (D-West Virginia) was also a designated survivor – that legislative survivor, rather than the surviving cabinet member, would become Acting President of the United States. However, it is unclear whether another legislator could do so without first being elected to that leadership position by a quorum of their respective house.

To date, no one other than a Vice President has been Acting President.

Powers, duties, status, and protocol

Under both the Twenty-fifth Amendment and the Presidential Succession Act, an Acting President has identical constitutional "powers and duties" as the President, being able to sign bills into law, petition Congress for a declaration of war, and perform other tasks, but does not hold the office of President itself. The incapacitated President remains the sole holder of the presidential office, although the powers and duties of the presidency are transferred to the Acting President. The President who is unable to exercise the powers and duties of the office remains the President of the United States during the period when there is an Acting President. In other words, the incapacitated President does not become an ordinary citizen. The President is deprived of the powers and duties of the office, but not of presidential status. Similarly, while the Vice President is discharging the powers and duties of the presidency pursuant to Sections 3 or 4 of the Twenty-fifth Amendment, he still holds the office of Vice President, and would be both Vice President and Acting President simultaneously.

Oath of office

A Vice President does not take the presidential oath of office when becoming Acting President. As stated above, an Acting President is not the same as President. An Acting President merely exercises the powers and duties of the President, without actually holding the office of President.

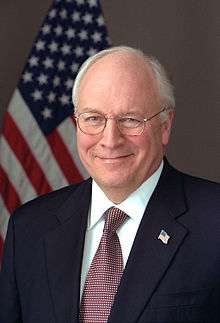

In the three occasions when the Twenty-fifth Amendment has been invoked, there is no record of the Vice President having taken the oath. In the case of the Amendment's second invocation by President George W. Bush in 2002, a detailed account of the procedure was subsequently given by the White House Press Secretary, and no mention whatsoever was made of the oath being taken by the Vice President. Instead, it is recorded that Vice President Cheney was informed by telephone that he was now Acting President once the invocation letters signed by the President were transmitted to the Speaker of the House and the President pro tempore of the Senate.[5] Likewise, there is no historical record of Vice President George H. W. Bush taking the oath when he filled in for President Ronald Reagan during Reagan's colon surgery nor of Cheney taking the oath the second time he assumed George W. Bush's presidential duties.

It should be noted, however, that the Presidential Succession Act of 1947 (that applies only when there is neither a President nor a Vice President able to discharge the powers and duties of the office) makes reference to the oath, albeit in an indirect manner. It states that the Speaker of the House of Representatives, the President pro tempore of the Senate, and the mentioned members of the Cabinet, upon being called to act as President, shall resign from office, and, in the section referring to members of the Cabinet acting as President, it states that the taking of the oath of office by one person so called to act as President shall be held to constitute the said person's resignation from the Cabinet office by virtue of the holding of which he qualifies to act as President. However, the Act stops short of explicitly requiring the presidential oath to be taken. In any event, the Presidential Succession Act does not apply when the Vice President is the one in place to act as President.

Term of service

An Acting President serves until:

- The President transmits a written declaration to the Speaker of the House of Representatives and the President pro tempore of the Senate, declaring that his period of incapacity has ended, if the incapacity was declared under Section 3 of the Twenty-fifth Amendment (self declared incapacity); or,

- The President transmits a written declaration to the Speaker of the House of Representatives and the President pro tempore of the Senate declaring that he is able to resume the powers and duties of his office and four days elapse without the Vice President and a majority of the Cabinet restating their declaration that the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, if the incapacity was declared under section 4 of the Twenty-fifth Amendment (action by Vice President and a majority of the Cabinet).

- Twenty-one days elapse after the receipt, under Section 4 of the Twenty-fifth Amendment, of the declaration of the Vice President and Cabinet, declaring, within four days of the President having declared that he was able to resume the powers and duties of his office, that they still believe that the President is unable to discharge those powers and duties, but only if Congress does not, within that period of twenty-one days, determine, by a two-thirds vote in both Houses, that the President is indeed incapable of exercising his powers and duties.

- The death, resignation (it is not clear, however, if an incapacitated President would still be able to resign the office after his incapacity had been declared) or removal of the President. In this case a Vice President acting as President would succeed to the office. Any other officer acting as President, however, would (per the terms of the Presidential Succession Act of 1947) serve out the remainder of the Presidential term as Acting President instead of becoming President.

- A President elect or Vice President elect qualifying to hold the office, in a case in which the Presidential Succession Act has entered into operation due to the failure of both a President elect and a Vice President elect to qualify.

- A person mentioned in subsections (a) or (b) of 3 U.S.C. § 19 (the codification of the Presidential Succession Act of 1947)--that is, the Speaker of the House of Representatives or President pro tempore of the Senate—becoming able to act as President, when those powers and duties are being exercised by a member of the Cabinet under subsection (d) in virtue of there being no Speaker or President pro tempore able to act upon the entry into operation of the provisions of the statute. In this case, however, an Acting President would be merely replaced by another Acting President placed higher in the order of succession.

- At the expiration of the term for which the elected President was chosen, whereupon the President elect would take office.

History of Acting Presidents

The only occasions when the office of Acting President came into existence were instances of invocations of Section 3 of the Twenty-fifth Amendment.

Neither Section 4 of the Twenty-fifth Amendment, nor the Presidential Succession Act of 1947 or its predecessor acts have ever come into operation.

Invocations of Twenty-fifth Amendment

Only three times in American history has someone acted as President. In all cases, the self-declared incapacity method was used by a President to voluntarily transfer presidential authority to his Vice President while the President was under anesthesia for a medical procedure; coincidentally, all the procedures involved the respective President's large intestine:[1]

- On July 13, 1985, President Ronald Reagan underwent surgery to remove cancerous polyps from his colon. Prior to undergoing surgery, he transmitted a letter to Speaker of the House of Representatives Tip O'Neill and President pro tempore of the Senate Strom Thurmond declaring his incapacity. Vice President George H. W. Bush then acted as President from 11:28 until 19:22, when Reagan transmitted a second letter to resume the powers and duties of the office.

- On June 29, 2002, President George W. Bush declared himself temporarily unable to discharge the powers and duties of the office prior to undergoing a colonoscopy which was done under sedation. He invoked Section 3 of the Twenty-fifth Amendment in letters (full text) given to White House Counsel Alberto Gonzales, who transmitted them by fax to Speaker of the House of Representatives Dennis Hastert and President pro tempore of the Senate Robert Byrd. Gonzales called Hastert's and Byrd's offices to confirm receipt of the letters, and then contacted Vice President Dick Cheney to advise him of the transfer.[6] Cheney was Acting President for a little over two hours that day (from 07:09 to 09:24), whereupon Bush transmitted a second set of letters to resume the powers and duties of the office. Just nine months after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, and with US troops at war in Afghanistan, President Bush was intent on ensuring that in the event of a crisis there would be no question of Cheney's authority. When asked by the press about the decision to transfer power, President Bush replied "I did so because we're at war and I just want to be super — you know, super cautious."[7] Although the public was aware that the temporary handover would take place, for security purposes the time that it actually occurred was not revealed until after Bush resumed his duties as President.[8]

- On July 21, 2007, under the same circumstances as the 2002 invocation, President George W. Bush transmitted a letter to President pro tempore of the Senate Robert Byrd and Speaker of the House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi declaring himself temporarily unable to discharge the powers and duties of the office prior to undergoing a colonoscopy which was done under sedation (text of letters to Congress). Vice President Cheney was Acting President from 07:16 to 09:21 that day, becoming the first Vice President to serve as Acting President more than once. The Weekly Standard excerpted a letter Cheney sent to his grandchildren while serving as Acting President (text of letter), which as of 2007, was the only written document known to have been signed by an Acting President of the United States. The letter was lampooned by Ana Marie Cox for Time Magazine.[9]

Other potential invocation situations

On March 30, 1981, another situation with the potential for the invocation of the 'Acting President' provision occurred when President Ronald Reagan was shot and wounded in an assassination attempt by John Hinckley, Jr. Though Reagan was clearly seen by his staff, Cabinet members, and others as incapacitated, Vice President George H. W. Bush refused to join the Cabinet in invoking the Twenty-fifth Amendment, feeling it would be akin to a coup d'état. Reagan eventually recovered, but constitutional scholars such as Herbert Abrams have opined that the Twenty-fifth Amendment should have been invoked in order to clarify the acting chain of command.[10]

See also

References

- 1 2 "Amendment25.com". amendment25.com.

- ↑ Christopher Klein (February 18, 2013). "The 24-Hour President". The History Channel. Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- ↑ "DomainMarket.com, The world's best brand new brands". DomainMarket.com, The world's best brand new brands. Archived from the original on May 12, 2012.

- ↑ Knoller, Mark (January 30, 2007). "One Night Spent A Heartbeat Away". CBS News.

- ↑ "Cnn Breaking News". CNN. February 7, 2001.

- ↑ CNN Transcripts (2002-06-29). "White House Physician Provides Update on Bush's Condition". Retrieved 2006-06-04.

- ↑ "Remarks by the President Upon Departure for Camp David" (Press release). The White House, Office of the Press Secretary. 2002-06-28. Retrieved 2006-06-04..

- ↑ The White House, Office of the Press Secretary (2002). "News releases for June 2002". Retrieved 2006-06-04.

- ↑ "Grandpa Cheney". TIME.com.

- ↑ "The President Has Been Shot: Confusion, Disability, and the 25th Amendment in the Aftermath of the Attempted Assassination of Ronald Reagan: Herbert L. Abrams: 9780393030426: Amazon.com: Books". amazon.com.

External links

- US Code: Title 3, Chapter 1,section 19

- Presidential Line of Succession Examined, September 20, 2003

- Amendment25.com