Acoma Pueblo

|

Acoma | |

| |

|

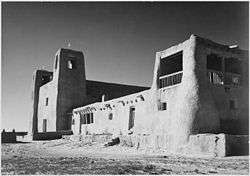

Dwellings on the mesa at Acoma Pueblo | |

Acoma Pueblo Location in New Mexico | |

| Location | Cibola County, New Mexico, USA |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Grants, New Mexico |

| Coordinates | 34°53′47″N 107°34′55″W / 34.89639°N 107.58194°WCoordinates: 34°53′47″N 107°34′55″W / 34.89639°N 107.58194°W |

| Built | circa 1100 |

| Architect | vernacular |

| Architectural style | Pueblo, Colonial |

| NRHP Reference # | 66000500[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

| Designated NHL | October 9, 1960[2] |

Acoma Pueblo (/ˈækəmə/; Western Keresan: Aa'ku; Zuni: Hakukya; Navajo: Haakʼoh) is a Native American pueblo approximately 60 miles (97 km) west of Albuquerque, New Mexico in the United States. Three villages make up Acoma Pueblo: Sky City (Old Acoma), Acomita, and Mcartys. The Acoma Pueblo tribe is a federally recognized tribal entity.[3] The historical land of Acoma Pueblo totaled roughly 5,000,000 acres (2,000,000 ha). Only 10% of this land remains in the hands of the community within the Acoma Indian Reservation.[4]

According to the 2010 United States Census, 4,989 people identified as Acoma.[5] The Acoma have continuously occupied the area for more than 800 years,[6] making it one of the oldest continuously inhabited communities in the United States.[7] Acoma tribal traditions estimate that they have lived in the village for more than two thousand years.[8]

Etymology

The word "Acoma" is from the Acoma word "acoma", or "Acú", which means "the place that always was" or "People of the White Rock". "Pueblo" is Spanish for "village" or "town". Pueblo refers to both the people and the unique architecture of the Southwest.[4] Some tribal elders assert that it means "a place that always was".[7]

Language

The Acoma language falls in the Keresan language group.[4] In Contemporary Acoma Pueblo culture, most people speak both Acoma and English. Elders might also speak Spanish.[3]

History

Origins and early history

Pueblo people are believed to have descended from the Anasazi, Mogollon, and other ancient peoples. These influences are seen in the architecture, farming style, and artistry of the Acoma. In the 13th century, the Anasazi abandoned their canyon homelands due to climate change and social upheaval. For upwards of two centuries migrations occurred in the area, and Acoma Pueblo would emerge by the thirteenth century.[4] This early founding date makes Acoma Pueblo one of the earliest continuously inhabited communities in the United States.[9][10]

The Pueblo lies on a 365 feet (111 m) mesa, about 60 miles (97 km) west of Albuquerque, New Mexico. The isolation and location of the Pueblo has sheltered the community for more than 1,200 years, which sought to avoid conflict with neighboring Navajos and Apaches.[10]

European contact

The Acoma Pueblo had contact with Spanish explorers heading north from Central America, all generally recorded as peaceful interactions.[10] Francisco Vásquez de Coronado's expedition described the Pueblo in 1540 as "one of the strongest places we have seen." Upon visiting the Pueblo the expedition "repented having gone up to the place." The only access to the Acoma Pueblo during this time was a set of almost vertical stairs cut into the rock face. It is believed Coronado's expedition was the first European contact with the Acoma.[10]

By 1598, relationships with the Spaniards had declined. In December of that year, the Acoma heard that Juan de Oñate had intended on colonizing the area. The Acoma ambushed a group of Oñate's men, killing 11 of them, including Oñate's nephew. The Spanish took revenge on the Acoma, burning most of the village and killing more than 600 people and imprisoning approximately 500 others. Prisoners of war were forced into slavery and men over 25 years old had their right foot amputated. A row of houses on the north side of the mesa still retain marks from the fire started by a cannon during the Acoma War.[10]

Survivors of the Acoma massacre would recover and rebuild their community and Oñate would proceed to force the Acoma and other local Indians to pay taxes in crops, cotton, and labor. Spanish rule also brought Catholic missionaries into the area. The Spanish renamed the pueblos with the names of saints and started to construct churches at them. New crops also were introduced to the Acoma, including peaches, peppers, and wheat. A royal decree in 1620 created civil offices in each pueblo, including Acoma, with a governor to go along with the office. In 1680 the Pueblo Revolt took place, with Acoma participating.[10] The revolt brought refugees from other pueblos. Those who eventually left Acoma would go on to form Laguna Pueblo.[11]

The Acoma then suffered from smallpox epidemics and raiding from the Apache, Comanche, and Ute. On occasion, the Acoma would side with the Spanish to fight against nomadic tribes. The Acoma proceeded to practice their religion in secrecy. Intermarriage and interaction also became common among the Acoma, other pueblos, and Hispanic villages. These communities would intermingle to form the culture of New Mexico.[12]

San Esteban Del Rey Mission

Between 1629 and 1641 Father Juan Ramirez oversaw construction of the San Estevan Del Rey Mission Church church. The Acoma were ordered to build the church, moving 20,000 short tons (18,000 t) of adobe, straw, sandstone, and mud to the mesa for the church walls. Ponderosa pine was brought in by community members from Mount Taylor, over 40 miles (64 km) away. At 6,000 square feet (560 m2), with an altar flanked by 60 feet (18 m)-high wood pillars hand carved in red and white designs representing Christian and Indigenous beliefs, the structure is considered a cultural treasure by the Acoma, despite the slave labor used to build it. In 1970 it was placed on the National Register of Historic Places[13] and in 2007 it became the 28th designated National Trust Historic Site; the only Native American site designated with the latter title.[10]

19th and 20th century

During the nineteenth century, the Acoma people, while trying to uphold traditional life, also adopted aspects of the once-rejected Spanish culture and religion. By the 1880s, railroads brought the pueblos out of isolation. In the 1920s, the All Indian Pueblo Council gathered for the first time in more than 300 years. Responding to congressional interest in appropriating Pueblo lands, the U.S. Congress passed the Pueblo Lands Act in 1924. Despite successes in retaining their land, the twentieth century proved difficult for the survival of cultural traditions for the Acoma. Protestant missionaries and schools came into the area and the Bureau of Indian Affairs forced Acoma children into boarding schools. By 1922, most children from the community were in boarding schools.[12]

Present day

Today, about 300 two- and three-story adobe buildings reside on the mesa, with exterior ladders used to access the upper levels where residents live. Access to the mesa is by a road blasted into the rock face during the 1950s. Approximately 30[11] or so people live permanently on the mesa, with the population increasing on the weekends as family members come to visit and tourists, some 55,000 annually, visit for the day.

Acoma Pueblo has no electricity, running water, or sewage disposal.[11] A reservation surrounds the mesa, totaling 600 square miles (1,600 km2). Tribal members live both on the reservation and outside it.[10] contemporary Acoma culture remains relatively closed, however.[3] According to the 2000 United States census, 4,989 people identify themselves as Acoma.[5]

Many Acoma people disapprove of Juan de Oñate being called New Mexico's founder. In 1998, after a statue was erected as a tribute to Oñate at the Oñate Monument Center in Alcalde, someone cut off the bronze right foot of his statue with a chainsaw.[10]

Culture

Governance and reservation

Acoma government was maintained by two individuals: a cacique, or head of the Pueblo, and a war captain, who would serve until their deaths. Both individuals maintained strong religious connections to their work, representing the theocracy of Acoma governance. The Spanish eventually imposed a group to oversee the Pueblo, but, their power was not taken seriously by the Acoma. The Spanish group would work with external situations and comprised a governor, two lieutenant governors, and a council. The Acoma also participated in the All Indian Pueblo Council, which started in 1598 and arose again in the twentieth century.[14]

Today, the Acoma controls approximately 500,000 acres (200,000 ha) of their traditional land. Mesas, valleys, hills, and arroyos dot the landscape that averages about 7,000 feet (2,100 m) in altitude with about 10 inches (250 mm) of rain each year. Since 1977, the Acoma have increased their domain through several land purchases. On the reservation, only tribal members may own land and almost all enrolled members live on the property. The cacique is still active in the community, and is from the Antelope clan. The cacique appoints tribal council members, staff, and the governor.[3]

In 2011 Acoma Pueblo and the Pueblo of Santa Clara were victims of heavy flooding. New Mexico supplied more than $1 million to fund emergency preparedness and damage repair for victims and governor Susana Martinez requested additional funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency.[15]

Warfare and weaponry

Historically, engagements in warfare were common for Acoma, like other Pueblos. Weapons used included clubs, stones, spears, and darts. The Acoma later would serve as auxiliaries for forces under Spain and Mexico, fighting against raids and protecting merchants on the Santa Fe Trail. After the nineteenth-century raiding tribes were less of a threat and Acoma military culture began to decline. The war captain position eventually would change to a civil and religious function.[6]

Architecture

Acoma Pueblo has three rows of three-story, apartment-style buildings which face south on top of the mesa. The buildings are constructed from adobe brick with beams across the roof that were covered with poles, brush, and then plaster. The roof for one level would serve as the floor for another. Each level is connected to others by ladders, serving as a unique defensive aid; the ladders are the only way to enter the buildings, as the traditional design has no windows or doors. The lower levels of the buildings were used for storage. Baking ovens are outside the buildings, with water being collected from two natural cisterns. Acoma also has seven rectangular kivas and a village plaza which serves as the spiritual center for the village.[14]

Family life

About 20 matrilineal clans were recognized by the Acoma. Traditional child rearing involved very little discipline. Couples were generally monogamous and divorce was rare. Funerary rites involved ceremony and quick burial after death, followed by four days and nights of vigil. Women would wear cotton dresses and sandals or high moccasin boots. Traditional clothing for men involved cotton kilts and leather sandals. Rabbit and deer skin was used for clothing and robes, as well.[6] In the seventeenth century horses were introduced to the Pueblo by the Spanish. Education was overseen by kiva headmen who taught about human behavior, spirit and body, astrology, ethics, child psychology, oratory, history, dance, and music.[6]

Since the 1970s Acoma Pueblo has retained control over education services, which have been keys in maintaining traditional and contemporary lifestyles. They share a high school with Laguna Pueblo. Alcoholism, drug use, and other health issues are prominent on the reservation and Indian Health Service hospitals and native healers cooperate to battle health problems. Alcohol is banned on the Pueblo.[16] The nearest hospital is at Laguna Pueblo. Today, 19 clans still remain active.[3]

Religion

Traditional Acoma religion stresses harmony between life and nature. The sun is a representative of the Creator deity. Mountains surrounding the community, the sun above, and the earth below help to balance and define the Acoma world. Traditional religious ceremonies may revolve around the weather, including seeking to ensure healthy rainfall. The Acoma also use kachinas in rituals. The Pueblos also had one or more kivas, which served as religious chambers. The leader of each Pueblo would serve as the community religious leader, or cacique. The cacique would observe the sun and use it as a guide for scheduling ceremonies, some which were kept secret.[12]

Many Acoma are Catholic, but blend aspects of Catholicism and their traditional religion. Many old rituals are still performed.[3] In September, the Acoma honor their patron saint, Saint Stephen. For feast day, the mesa is opened to the public for the celebration. More than 2,000 pilgrims attend the San Esteban Festival. The celebration begins at San Esteban Del Rey Mission and a carved pine effigy of Saint Stephen is removed from the altar and carried into the main plaza with people chanting, shooting rifles, and the ringing of steeple bells. The procession then proceeds past the cemetery, down narrow streets, and to the plaza. Upon arriving at the plaza, the effigy is placed in a shrine lined with woven blankets, which is guarded by two Acoma men. A celebration follows with dancing and feasting. During the festival vendors sell goods, such as traditional pottery and cuisine.[10]

Subsistence

Before contact with the Spanish, Acoma people ate corn, beans, and squash, primarily. Mut-tze-nee was a popular thin corn bread. They also raised turkeys, tobacco, and sunflowers. The Acoma hunted antelope, deer, and rabbits. Wild seeds, berries, nuts, and other foods were gathered. After 1700 new foods are noted in the historical record. Blue corn drink, pudding, corn mush, corn balls, wheat cake, peach-bark drink, paper bread, flour bread, wild berries, and prickly pear fruit all became staples. After contact with the Spanish, goats, horses, sheep and donkeys were raised.[6]

In contemporary Acoma, other foods are also popular such as apple pastries, corn tamales, green-chili stew with lamb, fresh corn, and wheat pudding with brown sugar.[10]

Irrigation techniques such as dams and terraces were used for agricultural purposes. Farming tools were made of wood and stone. Harvested corn would be ground with hands and mortar.[6]

Economy

Historical Acoma economic practices are described as socialistic or communal. Labor was shared and produce was distributed equally. Trading networks were extensive, spreading thousands of miles throughout the region. During fixed times in the summer and fall, trading fairs were held. The largest fair was held in Taos by the Comanche. Nomadic traders would exchange slaves, buckskins, buffalo hide, jerky, and horses. Pueblo people would trade for copper and shell ornaments, macaw feathers, and turquoise. The Acoma would trade via the Santa Fe Trail starting in 1821, and with the arrival of railroads in the 1880s, the Acoma became dependent on American-made goods. This dependency would cause traditional arts such as weaving and pottery making to decline.[6]

Today, the Acoma produce a variety of goods for economic benefit. Agriculturally they grow alfalfa, oats, wheat, chilies, corn, melon, squash, vegetables, and fruit. They raise cattle and have natural reserves of gas, geothermal, and coal resources. Uranium mines in the area provided work for the Acoma until their closings in the 1980s, after that, the tribe has provided most employment opportunities, however, high unemployment rates trouble the Pueblo. The legacy of the uranium mines has left radiation pollution, causing the tribal fishing lake to be drained and some health problems within the community.[3]

Tourism

Tourism is a major source of income for the tribe.[3] In 2008 Pueblo Acoma opened the Sky City Cultural Center and Haak'u Museum at the base of the mesa, replacing the original, which was destroyed by fire in 2000. The center and museum seek to sustain and preserve Acoma culture. Films about Acoma history are shown and a café serves traditional foods. The architecture was inspired by pueblo design and indigenous architectural traditions with wide doorways in the middle, which in traditional homes make the bringing of supplies easier, and flecks of mica are in the windowpanes, a mineral which is used to create mesa windows. The complex is also fire resistant, unlike traditional pueblos, and they are painted light pinks and purples, to match the landscape surrounding it. Traditional Acoma artwork is exhibited and demonstrated at the Center, including ceramic chimneys crafted on the rooftop.[10] Arts and crafts also bring income into the community.[3]

Acoma Pueblo is open to the public by guided tour the majority of the year. Photography of the Pueblo and surrounding land is restricted. Tours and camera permits are purchased at the Sky City Cultural Center.[3] While photography may be produced with permit, video recordings, drawings, and sketching are prohibited.[17]

The Acoma Pueblo also has a casino and hotel, the Sky City Casino Hotel. The casino and hotel are alcohol-free and it is maintained by the Acoma Business Enterprise, which oversees most Acoma businesses.[16]

Arts

At Acoma, pottery remains one of the most notable artforms. Men created weavings and silver jewelry, as well.[6]

Acoma pottery

Acoma pottery dates back to more than 1,000 years ago. Dense local clay, dug up at a nearby site, is essential to Acoma pottery. The clay is dried and strengthened by the addition of pulverized pottery shards. The pieces then are shaped, painted, and fired. Geometric patterns, thunderbirds, and rainbows are traditional designs, which are applied with the spike of a yucca. Upon completion, a potter would lightly strike the side of the pot, and hold it to their ear. If the pot does not ring, then the pot will crack during firing. If this was found, the piece would be destroyed and ground into shards for future use.[10]

Communities

.jpg)

Acoma Pueblo people

- Marie Chino, traditional pottery artist

- Vera Chino, traditional pottery artist

- Lucy Lewis, traditional pottery artist

- Simon J. Ortiz, poet, author, and educator

- Anton Docher, "The Padre of Isleta", served as a priest in Acoma during his long period in Isleta.[18]

See also

- San Estevan Del Rey Mission Church

- Acoma Indian Reservation

- List of Indian reservations in the United States

- Solomon Bibo

- Enchanted Mesa

References

Notes

- ↑ Staff (2007-01-23). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ "Acoma Pueblo". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-06-14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Barry Pritzker (2000). A Native American encyclopedia: history, culture, and peoples. Oxford University Press. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-0-19-513897-9. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Barry Pritzker (2000). A Native American encyclopedia: history, culture, and peoples. Oxford University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-19-513897-9. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- 1 2 U.S. Census Bureau, Census 2000 Census 2000 American Indian and Alaska Native Summary File (AIANSF) - Sample Data, Acoma alone, H38

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Barry Pritzker (2000). A Native American encyclopedia: history, culture, and peoples. Oxford University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-19-513897-9. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- 1 2 "Acoma Pueblo." U*X*L Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. U*X*L. 2008. Retrieved August 14, 2012 from HighBeam Research: http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G2-3048800041.html

- ↑ Acoma Pueblo, Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes, January 1, 2008

- ↑ "Lucy M. Lewis Dies; Self-Taught Potter, 93". Obituaries. New York Times. 1992.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 David Zax (2008). "Ancient Citadel". Travel. Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- 1 2 3 "Acoma". Pueblo. Holmes Anthropology Museum. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- 1 2 3 Barry Pritzker (2000). A Native American encyclopedia: history, culture, and peoples. Oxford University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-19-513897-9. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ↑ Charles W. Snell (April 30, 1968). "National Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings: San Estevan del Rey Mission Church (Acoma)" (pdf). National Park Service. and Accompanying photos, exterior and interior, from 19 PDF (32 KB)

- 1 2 Barry Pritzker (2000). A Native American encyclopedia: history, culture, and peoples. Oxford University Press. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0-19-513897-9. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ↑ Shaun Griswold (2011). "Gov. Susana Martinez requests federal funding for flood victims". KOB. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- 1 2 Neala Schwartzberg (2006). "Acoma Pueblo, Sky City Cultural Center and Haak'u Museum". Offbeat Travel. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ↑ "Acoma and Laguna Pueblos: Planning a Trip", Frommers Guide

- ↑ Keleher and Chant. The Padre of Isleta. Sunstone Press, 2009, chap.4- p. 30.36.

Further reading

- Minge, Ward Alan and Simon Ortiz. Acoma: Pueblo in the Sky. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press (1991). ISBN 0-8263-1301-9

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Acoma Pueblo. |

- Official Acoma Pueblo website

- Official Sky City Cultural Center and Haak'u Museum website

- Official Sky City Casino and Hotel website

- AcomaZuni.com: Acoma "Sky City"

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. NM-6, "Pueblo of Acoma, Casa Blanca vicinity, Acoma Pueblo, Cibola County, NM", 87 photos, 86 measured drawings, 10 data pages, 1 photo caption page

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||