Sudan cheetah

| Sudan cheetah | |

|---|---|

| |

| A female Sudan cheetah in Zoo Landau, Germany. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Genus: | Acinonyx |

| Species: | A. jubatus |

| Subspecies: | A. j. soemmeringii |

| Trinomial name | |

| Acinonyx jubatus soemmeringii (Fitzinger, 1855) | |

| |

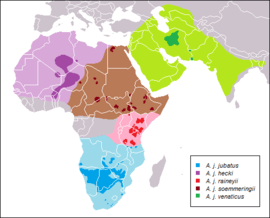

| A. j. soemmeringii range (brown) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Acinonyx jubatus megabalica | |

The Sudan cheetah[1] (Acinonyx jubatus soemmeringii) is a cheetah subspecies from Central and Northeast Africa. It lives in fragmented areas of the Sudan, Ethiopia, Somalia and the Central African Republic. It is also commonly known as Somali cheetah,[2] Northeast African cheetah or Central African cheetah.

Once widespread throughout central to northeast Africa, it was driven to extinction in Cameroon, Nigeria and Egypt. In the 1970s, the Sudan cheetah population of the Northeast region was estimated at 1,150 to 4,500 individuals.[3] Since 2002, it is classified as Vulnerable by IUCN, due to low densities, habitat loss and being smuggled from the Horn of Africa to the Middle East, and the Sudan cheetah population has been estimated at fewer than 2,000 cheetahs in the wild.[4] The population is still increasing slowly due to conservation efforts and breeding programs in Europe and the Middle East.

Once thought to be genetically identical to other Sub-Saharan cheetahs, it has been revealed that the Sudan cheetah is a distinct subspecies after being separated from their Southern African relative between 16,000 and 72,000 years ago.[5][6]

Taxonomy

In 1855, the Austrian zoologist Leopold Fitzinger proposed the trinomen Acinonyx jubatus soemmeringii for the cheetah subspecies living in Northeast and Central Africa, naming the species after German physicist Samuel Thomas von Soemmerring. The subspecies may also be respectively known as "Soemmerring's cheetah".

Following Fitzinger's trinomen, other zoologists proposed two more trinomen for the Northern cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus megabalica and Acinonyx jubatus wagneri), however, they were nominated as different subspecies living in specific areas of Sudan. They are not recognized as subspecies, therefore are considered as synonyms for the Sudan cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus soemmeringii).

Evolutionary history

The closest relative of the Sudan cheetah is the South African cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus jubatus). It was unknown whether or not the subspecies from Sudan is genetically different from other cheetah population from other African regions and Iran to deserve their status as a separate subspecies. It has been revealed that the Northeast African cheetahs to be a completely distinct subspecies in January 2011, having been diverged from their Southern African cousins between 16,000 and 72,000 years ago, therefore is distinguish from their closest neighbors from Iran, the Asiatic cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus). It was also discovered that the Northeast African cheetahs had a lot in common with the Saharan cheetahs from West Africa.[5][6]

Physical characteristics

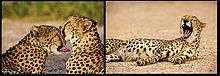

The Sudan cheetah, along with the Tanzanian cheetah, rank among the largest subspecies. Certain cheetahs can be smaller or medium-sized. However, it is the darkest in fur color. It has a densely tawny spotted coat with relatively thick and coarse fur in comparison to its relatives from eastern and northwestern Africa. It also has the largest and the most spread black spots. The belly of the Sudan cheetah is distinctly white while its breasts and throat can have some black spots similar to the eastern subspecies. This cheetah has distinct white patches around its eyes but the facial spotting can vary from very dense to relatively thin. The Sudan cheetah has been seen with both white and black tipped tails, although certain Sudan cheetahs' tails are white tipped. This subspecies' tail is also notably thick.

This subspecies has the largest head size, but sometimes can get relatively smaller, however, it does not have mustache markings. The tear marks of the Sudan cheetah are highly inconsistent, but they are frequently thickest at the mouth corners than the other four subspecies, making them quite unique.

The Sudan cheetah is the only subspecies not being reported to show a rare color variation. However, despite having the darkest fur color, certain Sudan cheetahs' fur color can be pale yellow or almost white as well.

In cold climates, such as in Whipsnade Zoo, Sudan cheetahs are the only African subspecies that can develop fluffy winter fur coats especially at very young age, though they are less developed than that of the Asiatic cheetah's.[7]

Habitat and population

Cheetahs live in wide open lands, savannahs, grasslands, semi-arid areas, mountainous regions and other open habitats where there is a large density of prey. The Sudan cheetah also thrive in deserts, steppes, including in regions of very hot tropical, humid and drier climate.

It is known there is the estimated total population of approximately 2,000 Sudan cheetahs in the wild, and there are apparently more in Ethiopia.[8] The Sudan cheetahs used to be widespread everywhere in central and northern Africa, ranging from the northern Democratic Republic of the Congo to Egypt. Currently, the population have lower density in their countries, unlike their eastern and southern cousins which are the most common, whilst the Northwest African and Asiatic cheetahs are listed as critically endangered. There is lower density in their current locations in other countries. The cheetahs are rarely seen in northern regions of Sudan, today they occur mostly on South Sudan. Wild cheetahs have been spotted in An Nil al Azraq, in the southeast region of Sudan.

The Sudan cheetahs are rarely seen outside of protected areas, although they can be spotted in various national parks and reserves, such as Manovo-Gounda St. Floris National Park, the Boma National Park and the Gambela National Park.

The cheetahs are often stated to be extinct in Egypt, although sightings of Northern cheetahs has been reported several times at the northern, western and northwestern parts of Qattara Depression. Finally, a conservation action plan was prepared for the cheetah and gazelle sancturary of present cheetah habitats in northwestern Qattara Depression.[9]

Former ranges

Other than those countries, the Northeast African cheetahs have been found in eastern parts of Nigeria, Niger, Cameroon, Chad, Eritrea, Djibouti, northern Somalia, Libya and Egypt. The subspecies might even shared borders with Northwest African and Tanzanian cheetahs. However, currently in the 21st century, the cheetah subspecies are thought to be regionally extinct in Nigeria and Libya.

Recently in July 2010, it was confirmed that the Northern cheetah, including the African wild dogs to be locally extinct in Cameroon.[10] The cheetahs, formerly extinct from Djibouti, are being reintroduced and bred at a wildlife refuge of the country. It is officially extinct in Eritrea.[11]

Prey

The Sudan cheetahs are carnivorous and mostly feed on herbivorous animals, such as Grant's gazelles, Soemmerring's gazelles, hares, guineafowls and large animals like zebras and ostriches on rare occasions.

History

Tamed cheetahs

.jpg)

Both continents of Africa and Asia had 100,000 cheetahs in the 19th century. Sudan cheetahs were once numerous in north, central and in the Horn of Africa. They ranged in Egypt and Libya on northern Africa, from Somalia to Niger on northeastern and central Africa. Cheetahs are known to be tamed, trained and to hunt herbivorous animals. Once existed in Egypt, the Ancient Egyptians often kept the cheetahs and raised them as pets, and also tamed and trained them for hunting mammals. Tamed cheetahs were taken to open hunting fields in low-sided carts or by horseback, hooded and blindfolded, and kept on leashes. When the prey was near enough, the cheetahs would be released to go after it.

This was the Egyptian tradition that was later passed on to the ancient Persians and brought to India, where the practice with Asiatic cheetahs was continued by Indian princes into the 12th century.

Threats

Like other cheetah subspecies, the Sudan cheetahs are threaten by illegal wildlife trade, hunting, poaching, habitat loss, lower densities of the population and lack of prey which reduces their numbers, making them hard and rare to spot them in the wild.[12] These animals can be highly threaten by other predators such as lions, leopards, African wild dogs and hyenas, as they could kill the cheetahs or steal their food.

The Sudan cheetah is also highly threatened by illegal pet trade from Somaliland.[13] Cheetah cubs can be sold on the black market for over $10,000 but rescuing a single cub costs over three times that much, and the majority of captive cheetah cubs may die before they ever leave Africa.[14] Though it is known that there are an increasing rate of Northeast African cheetah cubs mostly from Somaliland being smuggled into the Middle Eastern countries, such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and especially Yemen.[15] Fortunately, captive breeding projects in Europe and in the Middle East are slowly increasing their numbers and have been successful so far.

Conservation

The Sudan cheetah is currently listed as vulnerable in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Animals. There are breeding programs from Europe and the Middle East for the Sudan cheetah, such as the European Endangered Species Programme (EEP) which is reserved for European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). The breeding programs have been successful.[16] The captive breeding projects for the Northern cheetah first started in the Middle East, after several years of population of Sudan cheetah decreasing due to cubs being used for commercial purposes.[17] Then European zoos started afterwards once the captive-born Sudan cheetahs from the Arabian peninsula were sent to Zoological collections of Europe in Netherlands and Germany.

Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation

The Sudan cheetah, including the African wild dog are considered as emblematic to Ethiopia.[18] A conservation project for wild animals started first in 2006 after "real lack of awareness in Ethiopia about the treatment of animals".[17] The conservation goal is to ensure the increasing populations of cheetahs and other threatened wild animals in Ethiopia.[19] Following the illegal pet trade of cheetah cubs of Somaliland to the Middle East, the Ethiopian Born Free Foundation had confiscated the cheetah cubs from Somalia and started a semi-captive breeding project for them in order to save the species and reintroduce them into the wild.[20] The rescued Somali cheetahs reside at Ensessakotteh in a spacious enclosure.[21][22]

Semi-captive breeding program

There is a reproduction programme for the Sudan cheetahs at the Djibouti Cheetah Refuge in Djibouti City, which first started in 2004.[23] The Djibouti Cheetah Refuge (also known as DECAN Cheetah Refuge) was first constructed in 2002 and the initial phase was opened in a year later.[24]

Rewilding project in Arabia

There is also a rewilding project from the Breeding Centre for Endangered Arabian Wildlife for the Sudan cheetahs breeding in wildlife parks and those in captivity in the Middle-East, such as in the Arabian Wildlife Park from Sir Bani Yas, the Al-Ain Zoo and Sharjah's Arabian Wildlife Centre from the United Arab Emirates.[25][26]

Cheetahs once lived in the Arabian Peninsula until they became regionally extinct everywhere in the wild of the Middle-East in the early 1970s. The rewilding project officially started in 2008, when four captive-born Sudan cheetahs have been reintroduced into the wild of Sir Bani Yas Island to roam free and maintain natural balance. The cheetahs are taught to breed, to survive and feed on goitered and mountain gazelle on their own, then their offsprings would successfully learn those instincts from their parents.[27]

Cheetahs are known to be difficult to breed and therefore, the survival rate of cheetah cubs are low in the wild and in captivity. However, the project has been successful so far. In April 2010, the first four Sudan cheetah cubs have been born on the island from a successfully rewilded Sudan cheetah mother named Safira. According to conservation team, the cubs' mother have done an impressive job in taking care of her children. The cubs are recognized to be the first wild-born cheetahs to ever been born in Arabia after 40 years ago.[28][29][30][31]

The Al-Wabra Wildlife Preservation (AWWP) from Qatar, Al-Dhaid Wildlife Centre from Sharjah, the Nakelee Wildlife Centre and the Wadi Al-Safa Wildlife Centre from Dubai are also part of the international breeding programme to help save the rare Sudan cheetah population which are breeding in captivity. The breeding programmes of the Middle-East are aiming to release the Sudan cheetah into the wild of Africa. There are currently 23 adult and 7 cubs in Wadi Al-Safa.[2][32]

In captivity

Cheetahs are known to be difficult to breed, especially in captivity. The Sudan cheetah has been breeding in captivity for many years in Arabian zoos, such as Al Ain Zoo and Arabian wildlife centers from Qatar, Sharjah and Dubai. The Northern cheetahs breeding in European zoos are found at Zoo Landau and Tierpark Berlin from Germany, the Chester Zoo, Bristol Zoo, Whipsnade Zoo and Marwell Zoo from the United Kingdom, Zoo de Cerza, Parc zoologique de Bordeaux Pessac and La Palmyre Zoo from France, the Plzeň Zoo from the Czech Republic, Zoo Santo Inácio from Portugal, the DierenPark Amersfoort and Beekse Bergen Safari Park from Netherlands. The Fota Wildlife Park from Ireland, which bred hundreds of South African cheetahs, has bred its first Northern cheetah in 2013.[33]

The first captive breeding projects for the Northeast African cheetah started in Sheikh Butti Al-Maktoum's Wildlife Centre in early 1994, then followed by the Sharjah's Arabian Breeding Centre in late 2002, until captive-bred Sudan cheetahs from the Middle East were sent to two European zoos, Zoo Landau and Beekse Bergen Safari Park. La Palmyre Zoo would receive the cheetahs 6 months later as well.

See also

References

- ↑ Murray Wrobel. "Elsevier's Dictionary of Mammals". Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- 1 2 "Al Wabra Wildlife Preservation (AWWP)" (PDF). Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ↑ T. M. Caro (1994). "Cheetahs of the Serengeti Plains: Group Living in an Asocial Species". Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ↑ "Cheetah, Acinonyx jubatus". Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- 1 2 Ella Davies (24 January 2011). "Iran's endangered cheetahs are a unique subspecies". Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- 1 2 Three distinct cheetah populations, but Iran's on the brink, 18 January 2011, retrieved 4 February 2015

- ↑ "Big Picture: Bedfordshire's Easter cheetahs". 29 March 2013. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ↑ "Past and present cheetah range map.". Cheetah.org. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- ↑ "Cheetah in North Africa". IUCN The World Conservation Union. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ↑ Jeremy Hance (28 July 2010). "Cameroon says goodbye to cheetahs and African wild dogs". Jeremy Hance. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ↑ Durant, S., Marker, L., Purchase, N., Belbachir, F., Hunter, L., Packer, C., Breitenmoser-Würsten, C., Sogbohossou, E. & Bauer, H. (2008). "Acinonyx jubatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2015.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature.

- ↑ "Friedman Cheetah Conservation Grants Program". Panthera.org. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ↑ DOTWnews (17 July 2014). "Cheetahs traded as ‘luxury pets’ in Middle East at risk of extinction". Destinations Of The World News. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ↑ "Three cheetah cubs to enjoy new life after rescue from illegal pet trade". Wildlife Extra News. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ↑ "Acinonyx jubatus (Cheetah, Hunting Leopard)". IUCNRedList.org. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- ↑ "Captive breeding of North African cheetah, Acinonyx jubatus soemmeringii" (PDF). September 2006. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- 1 2 Emily Wax (9 January 2006). "Cheetahs Find Rare Refuge Amid Poverty Of Ethiopia". The Washington Post. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ↑ "National action plan for the conservation of cheetah and African wild dog in Ethiopia" (PDF). 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ↑ "Ethiopia’s Cheetahs, Wild Dogs, and Lions Get National Action Plans". Wildlife Conservation Society. 19 April 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ↑ "Wildlife Conservation". Born Free Foundation Keep Wildlife In The Wild. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ↑ "Rescued cheetahs". Born Free Foundation Keep Wildlife In The Wild. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ↑ "The Centre". Born Free Foundation Keep Wildlife In The Wild. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ↑ "Endangered cheetah gives birth to three cubs in Djibouti". terradaily.com. 22 June 2006. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ↑ "DECAN Cheetah Reserve". DoDLive.mil. 1 December 2011. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ↑ Rayeesa Absal (6 April 2010). "Birth of four cubs signals return of cheetah to UAE". GulfNews.com. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ Binsal Abdul Kader (1 January 2011). "Rewilding of Cheetahs a big success in Sir Baniyas Island". GulfNews.com. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ John Henzell (22 February 2010). "Survival instinct kicks in for Sir Bani Yas cheetahs". TheNational.ae. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ↑ "First wild born cheetah for 40 years in Arabia". WildlifeExtra.com. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ↑ "Sir Bani Yas Island nature reserve is an ‘Arabian Ark’". News.com.au. 13 February 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ↑ "The Northern Cheetah finds a new home on Sir Bani Yas Island". SirBaniYasIsland.com. 15 April 2010. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ↑ Andy Sambidge (5 April 2010). "Baby cheetahs born on Abu Dhabi island". HotelierMiddleEast.com. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ↑ Colin Simpson (29 July 2012). "Wildlife centres in UAE toast births of cheetahs". TheNational.ae. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ↑ "FOTA CELEBRATES BIRTH OF 1st BABY CHEETAH IN 5 YEARS". FotaWildlife.ie. 25 October 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Acinonyx jubatus soemmeringii. |

- Species portrait Cheetah; IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group

- Sudan cheetah at the Encyclopedia of Life

- Cheetah Conservation Fund