Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction

| Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction | |

|---|---|

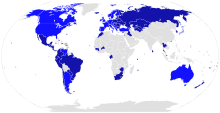

State parties to the convention

states that signed and ratified the convention)

states that acceded to the convention

state that ratified, but convention has not entered into force | |

| Signed | 25 October 1980 |

| Location | The Netherlands |

| Effective | 1 December 1983[1] |

| Parties | 93 (February 2015)[1] |

| Depositary | Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom of the Netherlands |

| Languages | French and English |

|

| |

The Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction (Dutch: Haags Kinderontvoeringsverdrag) or Hague Abduction Convention is a multilateral treaty developed by the Hague Conference on Private International Law (HCCH) that provides an expeditious method to return a child internationally abducted by a parent from one member country to another.

The Convention was concluded 25 October 1980 and entered into force between the signatories on 1 December 1983. The Convention was drafted to ensure the prompt return of children who have been abducted from their country of habitual residence or wrongfully retained in a contracting state not their country of habitual residence.[2]

The primary intention of the Convention is to preserve whatever status quo child custody arrangement existed immediately before an alleged wrongful removal or retention thereby deterring a parent from crossing international boundaries in search of a more sympathetic court. The Convention applies only to children under the age of 16.

As of February 2015, 93 states are party to the convention.[1] In 2014, the convention came into effect for Japan on April 1,[3] for Iraq on 1 July and for Zambia on 1 November.[1]

Procedural nature

| Family law |

|---|

|

Marriage and other equivalent or similar unions and status |

| Validity of marriages |

| Dissolution of marriages |

| Other issues |

| Private international law |

|

Family and criminal code (or criminal law) |

The Convention does not alter any substantive rights. The Convention requires that a court in which a Hague Convention action is filed should not consider the merits of any underlying child custody dispute, but should determine only that country in which those issues should be heard. Return of the child is to the member country rather than specifically to the left-behind parent.

The Convention requires the return of a child who was a “habitual resident” in a contracting party immediately before an action that constitutes a breach of custody or access rights.[4] The Convention provides that all Contracting States, as well as any judicial and administrative bodies of those Contracting States, “shall act expeditiously in all proceedings seeking the return of a children” and that those institutions shall use the most expeditious procedures available to the end that final decision be made within six weeks from the date of commencement of the proceedings.[5]

Wrongful removal or retention

The Convention provides that the removal or retention of a child is “wrongful” whenever:

"a. It is in breach of rights of custody attributed to a person, an institution or any other body, either jointly or alone, under the law of the State in which the child was habitually resident immediately before the removal or retention; and

"b. at the time of removal or retention those rights were actually exercised, either jointly or alone, or would have been so exercised but for the removal or retention." These rights of custody may arise by operation of law or by reason of a judicial or administrative decision, or by reason of an agreement having legal effect under the law of the country of habitual residence.[6]

"From the Convention's standpoint, the removal of a child by one of the joint holders without the consent of the other, is . . . wrongful, and this wrongfulness derives in this particular case, not from some action in breach of a particular law, but from the fact that such action has disregarded the rights of the other parent which are also protected by law, and has interfered with their normal exercise."[7]

Habitual residence

The Convention mandates return of any child who was “habitually resident” in a contracting nation immediately before an action that constitutes a breach of custody or access rights. The Convention does not define the term “habitual residence,” but it is not intended to be a technical term. Instead, courts should broadly read the term in the context of the Convention’s purpose to discourage unilateral removal of a child from that place in which the child lived when removed or retained, which should generally be understood as the child’s “ordinary residence.” The child’s “habitual residence” is not determined after the incident alleged to constitute a wrongful removal or retention. A parent cannot unilaterally create a new habitual residence by wrongfully removing or sequestering a child. Because the determination of “habitual residence” is primarily a “fact based” determination and not one which is encumbered by legal technicalities, the court must look at those facts, the shared intentions of the parties, the history of the children’s location and the settled nature of the family prior to the facts giving rise to the request for return.[8]

Special rules of evidence

The Convention provides special rules for admission and consideration of evidence independent of the evidentiary standards set by any member nation. Article 30 provides that the Application for Assistance, as well as any documents attached to that application or submitted to or by the Central Authority are admissible in any proceeding for a child's return.[9] The Convention also provides that no member nation can require legalization or other similar formality of the underlying documents in context of a Convention proceeding.[10] Furthermore, the court in which a Convention action is proceeding shall “take notice directly of the law of, and of judicial or administrative decisions, formally recognized or not in the State of habitual residence of the child, without recourse to the specific procedures for the proof of that law or for the recognition of foreign decisions which would otherwise be applicable" when determining whether there is a wrongful removal or retention under the Convention.[11]

Limited defenses to return

The Convention limits the defenses against return of a wrongfully removed or retained child. To defend against the return of the child, the defendant must establish to the degree required by the applicable standard of proof (generally determined by the lex fori, i.e. the law of the state where the court is located):

(a) that Petitioner was not “actually exercising custody rights at the time of the removal or retention” under Article 13; or

(b) that Petitioner “had consented to or acquiesced in the removal or retention” under Article 13; or

(c) that more than one year has passed from the time of wrongful removal or retention until the date of the commencement of judicial or administrative proceedings, under Article 12; or

(d) that the child is old enough and has a sufficient degree of maturity to knowingly object to being returned to the Petitioner and that it is appropriate to heed that objection, under Article 13; or

(e) that “there is grave risk that the child’s return would expose the child to physical or psychological harm or otherwise place the child in an intolerable situation,” under Article 13(b); or

(f) that return of the child would subject the child to violation of basic human rights and fundamental freedoms, under Article 20.

Non-compliance

.jpg)

Noncompliance with the terms and spirit of the Hague Convention has been a particularly difficult problem in the practical implementation of the Convention. In 2014, the United States declared Brazil, Mexico, Romania, and Ukraine as "Countries with Enforcement Concerns."[13] Additional countries are listed and reference to the most recent report should be made by concerned parties.

The Cuellar Versus Joyce case[14] was an example of the difficulties facing left behind parents applying to the US Central Authority.

The U.S. Department of State has primary responsibility over incoming Hague Convention abduction cases since April 2008; however, the National Missing and Exploited Children organization provides technical assistance and resources to parents, attorneys, judges and law enforcement officials involved in incoming Hague Convention case.

The case of Sean Goldman, a four-year-old boy abducted to Brazil, gained widespread media attention after the abducting mother died during the birth of another child. The mother's family, resident in Brazil, fought Sean's American father in Brazilian court to gain custody over Sean and keep him in the country. Ultimately, though, the Brazilian Supreme Federal Tribunal decided the case constituted child abduction under the terms of the Hague Convention, and had Sean sent back to America to live with his father.

Interpretation of article 13b: no return in case of "grave risks"

The principal purpose of the Abduction Convention is to cause the prompt return of a child to his or her "habitual residence." In certain exceptional cases under Article 13b, the court's mandatory return obligation is changed to a discretionary obligation, specifically, "the judicial or administrative authority of the requested State is not bound to order the return of the child if the person, institution or other body which opposes its return establishes that there is a grave risk that his or her return would expose the child to physical or psychological harm or otherwise place the child in an intolerable situation." The duty to return a child is however not abrogated by a finding under Art. 13(b) but merely changes from mandatory to discretionary. Since the general intent of the Convention is to cause the return of a child to his or her "habitual residence," unless there are some powerful and compelling reasons otherwise the court should normally and routinely exercise its discretion and return the child to his or her "habitual residence".

In the primary source of interpretation for the Convention, the Explanatory Report, Professor E. Perez–Vera noted the following:

"it would seem necessary to underline the fact that the three types of exception to the rule concerning the return of the child must be applied only so far as they go and no further. This implies above all that they are to be interpreted in a restrictive fashion if the Convention is not to become a dead letter. In fact, the Convention as a whole rests upon the unanimous rejection of this phenomenon of illegal child removals and upon the conviction that the best way to combat them at an international level is to refuse to grant them legal recognition. The practical application of this principle requires that the signatory States be convinced that they belong, despite their differences, to the same legal community within which the authorities of each State acknowledge that the authorities of one of them—those of the child's habitual residence—are in principle best placed to decide upon questions of custody and access. As a result, a systematic invocation of the said exceptions, substituting the forum chosen by the abductor for that of the child's residence, would lead to the collapse of the whole structure of the Convention by depriving it of the spirit of mutual confidence which is its inspiration."

In spite of the spirit and intent of the Convention as conveyed by the Convention itself and further reinforced by the Perez–Vera report, Article 13b is frequently used by abductors as a vehicle to litigate the child's best interests or custody. Although Article 13(b) inquiries are not intended to deal with issues or factual questions appropriate for custody proceedings, many countries use article 13b to request psychological profiles, detailed evaluations of parental fitness, evidence concerning lifestyle and the nature and quality of relationships.[15]

State parties

| State | Date of entry into force | State | Date of entry into force | State | Date of entry into force | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albania | 1 August 2007 | Gabon | 1 March 2011 | Peru | 1 August 2001 | ||

| Andorra | 1 July 2011 | Georgia | 1 October 1997 | Poland | 1 November 1992 | ||

| Argentina | 1 June 1991 | Germany | 1 December 1990 | Portugal | 1 December 1983 | ||

| Armenia | 1 June 2007 | Greece | 1 June 1993 | Romania | 1 February 1993 | ||

| Australia | 1 January 1987 | Guatemala | 1 May 2002 | Russian Federation | 1 October 2011 | ||

| Austria | 1 October 1988 | Guinea | 1 February 2012 | Saint Kitts and Nevis | 1 August 1994 | ||

| Bahamas | 1 January 1994 | Honduras | 1 March 1994 | San Marino | 1 March 2007 | ||

| Belarus | 1 April 1998 | Hungary | 1 July 1986 | Serbia | 27 April 1992 | ||

| Belgium | 1 May 1999 | Iceland | 1 November 1996 | Seychelles | 1 August 2008 | ||

| Belize | 1 September 1989 | Ireland | 1 October 1991 | Singapore | 1 March 2011 | ||

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 6 March 1992 | Israel | 1 December 1991 | Slovakia | 1 February 2001 | ||

| Brazil | 1 January 2000 | Italy | 1 May 1995 | Slovenia | 1 June 1994 | ||

| Bulgaria | 1 August 2003 | Korea, Republic of | 1 March 2013 | South Africa | 1 October 1997 | ||

| Burkina Faso | 1 August 1992 | Latvia | 1 February 2002 | Spain | 1 September 1987 | ||

| Canada | 1 December 1983 | Lesotho | 1 September 2012 | Sri Lanka | 1 December 2001 | ||

| Chile | 1 May 1994 | Lithuania | 1 September 2002 | Sweden | 1 June 1989 | ||

| China, People's Republic of (Hong-Kong & Macao only, by continuation of UK & Portugal) | Luxembourg | 1 January 1987 | Switzerland | 1 January 1984 | |||

| Colombia | 1 March 1996 | Malta | 1 January 2000 | Thailand | 1 November 2002 | ||

| Costa Rica | 1 February 1999 | Mauritius | 1 June 1993 | The Republic of Macedonia | 1 December 1991 | ||

| Croatia | 1 December 1991 | Mexico | 1 September 1991 | Trinidad and Tobago | 1 September 2000 | ||

| Cyprus | 1 February 1995 | Moldova, Republic of | 1 July 1998 | Turkey | 1 August 2000 | ||

| Czech Republic | 1 March 1998 | Monaco | 1 February 1993 | Turkmenistan | 1 March 1998 | ||

| Denmark | 1 July 1991 | Montenegro | 3 June 2006 | Ukraine | 1 September 2006 | ||

| Dominican Republic | 1 November 2004 | Morocco | 1 June 2010 | United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland | 1 August 1986 | ||

| Ecuador | 1 April 1992 | Netherlands | 1 September 1990 | United States of America | 1 July 1988 | ||

| El Salvador | 1 May 2001 | New Zealand | 1 August 1991 | Uruguay | 1 February 2000 | ||

| Estonia | 1 July 2001 | Nicaragua | 1 March 2001 | Uzbekistan | 1 August 1999 | ||

| Fiji | 1 June 1999 | Norway | 1 April 1989 | Venezuela | 1 January 1997 | ||

| Finland | 1 August 1994 | Panama | 1 May 1994 | Zambia | 1 November 2015 | ||

| France | 1 December 1983 | Paraguay | 1 August 1998 | Zimbabwe | 1 July 1995 |

See also

- International child abduction

- Child abduction

- Child laundering

- Child harvesting

- List of international adoption scandals

- Hague Adoption Convention

- Hague Abduction Convention Compliance Reports (US)

- International Child Abduction Remedies Act (US)

- Hague Conference on Private International Law

|

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 "Status table: Convention of 25 October 1980 on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction". Hague Conference on Private International Law. 14 June 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ↑ Hague Convention, Preamble.

- ↑ Family Law Week, “Japan signs and ratifies the 1980 Hague Child Abduction Convention", January 26, 2014

- ↑ Hague Convention, Article 4.

- ↑ Hague Convention, Article 11.

- ↑ Hague Convention, Article 3.

- ↑ Elisa Perez–Vera, Explanatory Report: Hague Conference on Private International Law, in 3 Acts and Documents of the Fourteenth Session ("Explanatory Report"), 71, at 447–48

- ↑ Mozes v. Mozes, 239 F.3d 1067, 1073 (US 9th Cir. 2001) Case details on the INCADAT website

- ↑ Hague Convention, Article 30

- ↑ Hague Convention, Article 23.

- ↑ Hague Convention, Article 14

- ↑ US Department of State, Report on Compliance with the Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction, April 2009

- ↑ http://travel.state.gov/content/dam/childabduction/complianceReports/2014.pdf

- ↑ see Cuellar v Joyce, --- F.3d ----, 2010 WL 624886 (9th Cir.(Mont.)

- ↑ William M. Hilton (1997). "The Limitations on Art. 13(b) of The Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction done at the Hague on 25 Oct 1980". Retrieved 2009-06-12.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hague Abduction Convention. |

- Full Text of the Convention

- Explanatory Report by Elisa Perez-Vera

- INCADAT—Case-law database of different jurisdictions concerning the 1980 Hague Child Abduction Convention

- US State Department International—Parental Child Abduction—Compliance Report 2011

- Contracting States

- The Child Abduction Section of the Hague Conference website

- Case law and materials including Hebrew documents

- Hague Conference Guides to good practice

- The Hague Domestic Violence Project International Child Abduction and Domestic Violence

- Multiple perspectives on the implications of the Hague Convention