A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

Front cover of the first edition, published by B. W. Huebsch in 1916 | |

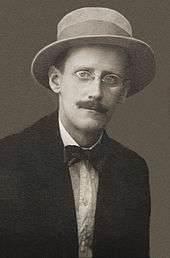

| Author | James Joyce |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Novel |

Publication date | 29 December 1916 |

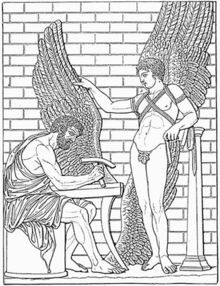

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is the first novel of Irish writer James Joyce. A Künstlerroman in a modernist style, it traces the religious and intellectual awakening of young Stephen Dedalus, a fictional alter ego of Joyce and an allusion to Daedalus, the consummate craftsman of Greek mythology. Stephen questions and rebels against the Catholic and Irish conventions under which he has grown, culminating in his self-exile from Ireland to Europe. The work uses techniques that Joyce developed more fully in Ulysses (1922) and Finnegans Wake (1939).

A Portrait began life in 1903 as Stephen Hero—a projected 63-chapter autobiographical novel in a realistic style. After 25 chapters, Joyce abandoned Stephen Hero in 1907 and set to reworking its themes and protagonist into a condensed five-chapter novel, dispensing with strict realism and making extensive use of free indirect speech that allows the reader to peer into Stephen's developing consciousness. American modernist poet Ezra Pound had the novel serialised in the English literary magazine The Egoist in 1914 and 1915, and published as a book in 1916 by B. W. Huebsch of New York. The publication of A Portrait and the short story collection Dubliners (1914) earned Joyce a place at the forefront of literary modernism.

In 1998, the Modern Library named the novel third on its list of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century.[1]

Background

Born into a middle-class family in Dublin, Ireland, James Joyce (1882–1941) excelled as a student, graduating from University College, Dublin, in 1902. He moved to Paris to study medicine, but soon gave it up. He returned to Ireland at his family's request as his mother was dying of cancer. Despite her pleas, the impious Joyce and his brother Stanislaus refused to make confession or take communion, and when she passed into a coma they refused to kneel and pray for her. James Joyce then took jobs teaching, singing and reviewing books, while drinking heavily.

Joyce made his first attempt at a novel, Stephen Hero, in early 1904. That June he met Nora Barnacle, with whom he eloped to Europe, first staying in Zürich before settling for ten years in Trieste (then in Austria-Hungary), where he taught English. There Nora gave birth to their children, George in 1905 and Lucia in 1907, and Joyce wrote fiction, signing some of his early essays and stories "Stephen Daedalus". The short stories he wrote made up the collection Dubliners (1914). He reworked the core themes of the novel Stephen Hero he had begun in Ireland in 1904 and abandoned in 1907 into A Portrait, published in 1916, a year after he had moved back to Zürich in the midst of the First World War.

Composition

Et ignotas animum dimittit in artes.

("And he turned his mind to unknown arts.")

At the request of its editors, Joyce submitted a work of philosophical fiction entitled "A Portrait of the Artist" to the Irish literary magazine Dana on 7 January 1904.[3] Dana's editor, W. K. Magee, rejected it, telling Joyce, "I can't print what I can't understand."[4] On his 22nd birthday, 2 February 1904, Joyce began a realist autobiographical novel, Stephen Hero, which incorporated aspects of the aesthetic philosophy expounded in A Portrait.[5] He worked on the book until mid-1905 and brought the manuscript with him when he moved to Trieste that year. Though his main attention turned to the stories that made up Dubliners, Joyce continued work on Stephen Hero. At 914 manuscript pages, Joyce considered the book about half-finished, having completed 25 of its 63 intended chapters.[6] In September 1907, however, he abandoned this work, and began a complete revision of the text and its structure, producing what became A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.[7] By 1909 the work had taken shape and Joyce showed some of the draft chapters to Ettore Schmitz, one of his language students, as an exercise. Schmitz, himself a respected writer, was impressed and with his encouragement Joyce continued work on the book.

In 1911 Joyce flew into a fit of rage over the continued refusals by publishers to print Dubliners and threw the manuscript of Portrait into the fire. It was saved by a "family fire brigade" including of his sister Eileen.[8] [7][lower-alpha 1] Chamber Music, a book of Joyce's poems, was published in 1907.[9]

Joyce showed, in his own words, "a scrupulous meanness" in his use of materials for the novel. He recycled the two earlier attempts at explaining his aesthetics and youth, A Portrait of the Artist and Stephen Hero, as well as his notebooks from Trieste concerning the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas expounded in the book in five carefully paced chapters.[10]

Stephen Hero is written from the point of view of an omniscient third-person narrator, but in Portrait Joyce adopts the free indirect style, a change that reflects the moving of the narrative centre of consciousness firmly and uniquely onto Stephen. Persons and events take their significance from Stephen, and are perceived from his point of view.[11] Characters and places are no longer mentioned simply because the young Joyce had known them. Salient details are carefully chosen and fitted into the aesthetic pattern of the novel.[12]

Publication history

In 1913 the Irish poet W. B. Yeats recommended Joyce's work to the avant-garde American poet Ezra Pound, who was assembling an anthology of verse. Pound wrote to Joyce,[13] and in 1914 Joyce submitted the first chapter of the unfinished Portrait to Pound, who was so taken with it that he pressed to have the work serialised in the London literary magazine The Egoist. Joyce hurried to complete the novel,[3] and it appeared in The Egoist in twenty-five instalments from 2 February 1914 to 1 September 1915.[14]

There was difficulty finding a British publisher for the finished novel, so Pound arranged for its publication by an American publishing house, B. W. Huebsch, which issued it on 29 December 1916.[3] The Egoist Press republished it in the United Kingdom on 12 February 1917 and Jonathan Cape took over its publication in 1924. In 1964 Viking Press issued a corrected version overseen by Chester Anderson. Garland released a "copy text" edition by Hans Walter Gabler in 1993.[14]

Major characters

Stephen Dedalus – The main character of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Growing up, Stephen goes through long phases of hedonism and deep religiosity. He eventually adopts a philosophy of aestheticism, greatly valuing beauty and art. Stephen is essentially Joyce's alter ego, and many of the events of Stephen's life mirror events from Joyce's own youth. His surname is taken from the ancient Greek mythical figure Daedalus, who also engaged in a struggle for autonomy.

Simon Dedalus – Stephen's father, an impoverished former medical student with a strong sense of Irish nationalism. Sentimental about his past, Simon Dedalus frequently reminisces about his youth. Loosely based on Joyce's own father and their relationship.

Emma Clery – Stephen's beloved, the young girl to whom he is fiercely attracted over the course of many years. Stephen constructs Emma as an ideal of femininity, even though (or because) he does not know her well.

Charles Stewart Parnell – An Irish political leader who is not an actual character in the novel, but whose death influences many of its characters. Parnell had powerfully led the Irish Parliamentary Party until he was driven out of public life after his affair with a married woman was exposed.

Cranly – Stephen's best friend at university, in whom he confides some of his thoughts and feelings. In this sense Cranly represents a secular confessor for Stephen. Eventually Cranly begins to encourage Stephen to conform to the wishes of his family and to try harder to fit in with his peers, advice that Stephen fiercely resents. Towards the conclusion of the novel he bears witness to Stephen's exposition of his aesthetic philosophy. It is partly due to Cranly that Stephen decides to leave, after witnessing Cranly's budding (and reciprocated) romantic interest in Emma.

Synopsis

Once upon a time and a very good time it was there was a moocow coming down along the road and this moocow that was coming down along the road met a nicens little boy named baby tuckoo ...His father told him that story: his father looked at him through a glass: he had a hairy face.

He was baby tuckoo. The moocow came down the road where Betty Byrne lived: she sold lemon platt.

— James Joyce, Opening to A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

The childhood of Stephen Dedalus is recounted using vocabulary that changes as he grows, in a voice not his own but sensitive to his feelings. The reader experiences Stephen's fears and bewilderment as he comes to terms with the world[15] in a series of disjointed episodes.[16] Stephen attends the Jesuit-run Clongowes Wood College, where the apprehensive, intellectually gifted boy suffers the ridicule of his classmates while he learns the schoolboy codes of behaviour. While he cannot grasp their significance, at a Christmas dinner he is witness to the social, political and religious tensions in Ireland involving Charles Stewart Parnell, which drive wedges between members of his family, leaving Stephen with doubts over which social institutions he can place his faith in.[17] Back at Clongowes, word spreads that a number of older boys have been caught "smugging"; discipline is tightened, and the Jesuits increase use of corporal punishment. Stephen is strapped when one of his instructors believes he has broken his glasses to avoid studying, but, prodded by his classmates, Stephen works up the courage to complain to the rector, Father Conmee, who assures him there will be no such recurrence, leaving Stephen with a sense of triumph.[18]

Stephen's father gets into debt and the family leaves its pleasant suburban home to live in Dublin. Stephen realises that he will not return to Clongowes. However, thanks to a scholarship obtained for him by Father Conmee, Stephen is able to attend Belvedere College, where he excels academically and becomes a class leader.[19] Stephen squanders a large cash prize from school, and begins to see prostitutes, as distance grows between him and his drunken father.[20]

As Stephen abandons himself to sensual pleasures, his class is taken on a religious retreat, where the boys sit through sermons.[21] Stephen pays special attention to those on pride, guilt, punishment and the Four Last Things (death, judgement, Hell, and Heaven). He feels that the words of the sermon are directed at himself and, overwhelmed, comes to desire forgiveness. Overjoyed at his return to the Church, he devotes himself to acts of repentance, though they soon devolve to mere acts of routine, as his thoughts turn elsewhere. His devotion comes to the attention of the Jesuits, and they encourage him to consider entering the priesthood.[22] Stephen takes time to consider, but has a crisis of faith because of the conflict between his spiritual beliefs and his aesthetic ambitions. Along Dollymount Strand he spots a girl wading, and has an epiphany in which he is overcome with the desire to find a way to express her beauty in his writing.[23]

As a student at University College, Dublin, Stephen grows increasingly wary of the institutions around him: Church, school, politics and family. In the midst of the disintegration of his family's fortunes his father berates him and his mother urges him to return to the Church.[24] An increasingly dry, humourless Stephen explains his alienation from the Church and the aesthetic theory he has developed to his friends, who find that they cannot accept either of them.[25] Stephen concludes that Ireland is too restricted to allow him to express himself fully as an artist, so he decides that he will have to leave. He sets his mind on self-imposed exile, but not without declaring in his diary his ties to his homeland:[26]

... I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.

Style

The novel mixes third-person narrative with free indirect speech, which allows both identification with and distance from Stephen. The narrator refrains from judgement. The omniscient narrator of the earlier Stephen Hero informs the reader as Stephen sets out to write "some pages of sorry verse," while Portrait gives only Stephen's attempts, leaving the evaluation to the reader.[27]

The novel is written primarily as a third-person narrative with minimal dialogue until the final chapter. This chapter includes dialogue-intensive scenes alternately involving Stephen, Davin and Cranly. An example of such a scene is the one in which Stephen posits his complex Thomist aesthetic theory in an extended dialogue. Joyce employs first-person narration for Stephen's diary entries in the concluding pages of the novel, perhaps to suggest that Stephen has finally found his own voice and no longer needs to absorb the stories of others.[28] Joyce fully employs the free indirect style to demonstrate Stephen's intellectual development from his childhood, through his education, to his increasing independence and ultimate exile from Ireland as a young man. The style of the work progresses through each of its five chapters, as the complexity of language and Stephen's ability to comprehend the world around him both gradually increase.[29] The book's opening pages communicate Stephen's first stirrings of consciousness when he is a child. Throughout the work language is used to describe indirectly the state of mind of the protagonist and the subjective effect of the events of his life.[30]

The writing style is notable also for Joyce's omission of quotation marks: he indicates dialogue by beginning a paragraph with a dash, as is commonly used in French, Spanish or Russian publications.

The novel, like all of Joyce's published works, is not dedicated to anyone.

Analysis

According to the literary scholar Hugh Kenner, "every theme in the entire life-work of James Joyce is stated on the first two pages of the Portrait".[31] The highly condensed recounting of young Stephen's growing consciousness "enact[s] the entire action [of the novel] in microcosm. An Aristotelian catalogue of senses, faculties, and mental activities is counterpointed against the unfolding of the infant conscience",[32] and themes that run through Joyce's later novels find expression there.[33]

The epigraph quotes from Ovid's Metamorphoses: the inventor Daedalus, who has built a labyrinth to imprison the Minotaur, and his son Icarus who are forbidden to leave the Island of Crete by its King, Minos. Daedalus, "turning his mind to unknown arts", fashions wings of birds' feathers and wax with which he and his son flee their island prison. Icarus flies so close to the sun that the wax on his pair melts and he plummets into the sea. To A. Nicholas Fargnoli and Michael Patrick Gillespie the epigraph parallels the heights and depths that end and begin each chapter, and can be seen to proclaim the interpretive freedom of the text.[2]

A Portrait belongs to the genres of Bildungsroman, the novel of education or coming of age, and Künstlerroman, a story of artistic development, of which A Portrait is the primary example in English.[34]

Autobiography

Stephen Hero is a directly autobiographical novel, including people and events because Joyce had personally experienced them. In contrast, in A Portrait Joyce refines his approach by selectively drawing on life events and reflecting them through the consciousness of Stephen Dedalus, a fictional character.[35]

Reception

A Portrait won Joyce a reputation for his literary skills, as well as a patron, Harriet Shaw Weaver, the business manager of The Egoist.[3]

In 1917 H. G. Wells wrote that "one believes in Stephen Dedalus as one believes in few characters in fiction," while warning readers of Joyce's "cloacal obsession," his insistence on the portrayal of bodily functions that Victorian morality had banished from print.[36]

Adaptations

A film version adapted for the screen by Judith Rascoe and directed by Joseph Strick was released in 1977. It features Bosco Hogan as Stephen Dedalus and T. P. McKenna as Simon Dedalus. John Gielgud plays Father Arnall, the priest whose lengthy sermon on Hell terrifies the teenage Stephen.[37]

Hugh Leonard's stage work Stephen D is an adaptation of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Stephen Hero. It was first produced at the Gate Theatre during the Dublin Theatre Festival of 1962.[38]

Notes

- ↑ The story is sometimes erroneously repeated as involving Stephen Hero and Joyce's common-law wife, Nora Barnacle. The error was first publicised by Joyce's patron Sylvia Beach in 1935, and was included in Herbert Gorman's biography James Joyce (1939).[7]

References

- ↑ "100 Best Novels". Random House. 1999. Retrieved 15 August 2014. This ranking was by the Modern Library Editorial Board of authors.

- 1 2 Fargnoli & Gillespie 2006, pp. 136–137.

- 1 2 3 4 Fargnoli & Gillespie 2006, p. 134.

- ↑ Fargnoli & Gillespie 2006, pp. 134–135.

- ↑ Fargnoli & Gillespie 2006, p. 154.

- ↑ Bulson (2006:47)

- 1 2 3 Fargnoli & Gillespie 2006, p. 155.

- ↑ Bulson (2006:47)

- ↑ Read 1967, p. 2.

- ↑ Johnson (2000:xviii)

- ↑ Johnson (2000:xvii)

- ↑ Johnson (2000:xvii)

- ↑ Read 1967, p. 1.

- 1 2 Herbert 2009, p. 7.

- ↑ Fargnoli & Gillespie 2006, p. 137.

- ↑ Fargnoli & Gillespie 2006, p. 136.

- ↑ Fargnoli & Gillespie 2006, p. 138.

- ↑ Fargnoli & Gillespie 2006, pp. 138–139.

- ↑ Fargnoli & Gillespie 2006, p. 139.

- ↑ Fargnoli & Gillespie 2006, pp. 139–140.

- ↑ Fargnoli & Gillespie 2006, p. 140.

- ↑ Fargnoli & Gillespie 2006, p. 141.

- ↑ Fargnoli & Gillespie 2006, pp. 141–142.

- ↑ Fargnoli & Gillespie 2006, p. 142.

- ↑ Fargnoli & Gillespie 2006, pp. 142—143.

- ↑ Fargnoli & Gillespie 2006, p. 143.

- ↑ Belanger 2001, p. xviii.

- ↑ Bulson (2006:51)

- ↑ Bulson (2006:50)

- ↑ Pericles Lewis. "A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man" (PDF). Cambridge Introduction to Modernism. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ↑ Kenner 1948, p. 365.

- ↑ Kenner 1948, p. 362.

- ↑ Kenner 1948, pp. 363–363.

- ↑ Bulson (2006:49)

- ↑ Bulson (2006:50)

- ↑ Wollaeger 2003, p. 4.

- ↑ A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Irish Playography, Stephen D by Hugh Leonard retrieved 7 July 2013

Works cited

- Belanger, Jacqueline (2001). "Introduction". A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Wordsworth Editions. pp. i–xxxii. ISBN 978-1-85326-006-3.

- Bulson, Eric (2006). "3". The Cambridge Introduction to James Joyce. Cambridge University Press. pp. 47–62. ISBN 0-521-84037-6.

- Fargnoli, A. Nicholas; Gillespie, Michael Patrick (2006). Critical Companion to James Joyce: A Literary Reference to His Life and Work. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-0848-3.

- Kenner, Hugh (Summer 1948). "The 'Portrait' in Perspective" 10 (3). Kenyon College. pp. 361–381. JSTOR 4332957.

- Read, Forrest, ed. (1967). Pound/Joyce; the Letters of Ezra Pound to James Joyce: With Pound's Essays on Joyce. New Directions Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8112-0159-9.

- Herbert, Stacey (2009). "Composition and publishing history of the major works: an overview". In McCourt, John. James Joyce in Context. Cambridge University Press. pp. 3–16. ISBN 978-0-521-88662-8.

- Johnson, Jeri (2000). "Introduction". A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Oxford world's classics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-283998-5.

- Wollaeger, Mark A. (2003). James Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: A Casebook. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-515076-6.

Further reading

- Attridge, Derek, ed. The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce, 2nd edition, Cambridge UP, 2004. ISBN 0-521-54553-6.

- Bloom, Harold. James Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. New York: Chelsea House, 1988. ISBN 1-55546-020-8.

- Brady, Philip and James F. Carens, eds. Critical Essays on James Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. New York: G. K. Hall, 1998. ISBN 978-0-7838-0035-6.

- Doherty, Gerald. Pathologies of Desire: The Vicissitudes of the Self in James Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. New York: Peter Lang, 2008. ISBN 978-0-8204-9735-8.

- Empric, Julienne H. The Woman in the Portrait: The Transforming Female in James Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. San Bernardino, CA: Borgo Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0-89370-193-2.

- Epstein, Edmund L. The Ordeal of Stephen Dedalus: The Conflict of Generations in James Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 1971. ISBN 978-0-8093-0485-1 .

- Harkness, Marguerite. Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: Voices of the Text. Boston: Twayne, 1989. ISBN 978-0-8057-8125-0.

- Morris, William E. and Clifford A. Nault, eds. Portraits of an Artist: A Casebook on James Joyce's Portrait. New York: Odyssey, 1962.

- Seed, David. James Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1992. ISBN 978-0-312-08426-4.

- Staley, Thomas F. and Bernard Benstock, ed. Approaches to Joyce's Portrait: Ten Essays. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1976. ISBN 978-0-82-293331-1.

- Thornton, Weldon. The Antimodernism of Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse UP, 1994. ISBN 978-0-8156-2587-2.

- Tindall, William York (1995). A Reader's Guide to James Joyce. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-0320-7.

- Wollaeger, Mark A., ed. James Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: A Casebook. Oxford and New York: Oxford UP, 2003. ISBN 978-0-19-515075-9.

- Yoshida, Hiromi. Joyce & Jung: The "Four Stages of Eroticism" in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. New York: Peter Lang, 2007. ISBN 978-0-8204-6913-3.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the novel: |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man |

- A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man at Project Gutenberg

- Hypertextual, self-referential version based on the Project Gutenberg edition, from an Imperial College London website

- Digitized copy of the first edition from Internet Archive

-

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man public domain audiobook at LibriVox

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man public domain audiobook at LibriVox - Study guide from SparkNotes

- Map of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|