A History of British Birds

Title page of 1847 edition | |

| Author | Thomas Bewick |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Thomas Bewick and workshop |

| Country | England |

| Subject | Birds |

| Genre | Natural history |

| Published | 1797-1804 (Bewick, Longman) |

A History of British Birds is a natural history book by Thomas Bewick, published in two volumes. Volume 1, "Land Birds", appeared in 1797. Volume 2, "Water Birds", appeared in 1804. A supplement was published in 1821. The text in "Land Birds" was written by Ralph Beilby, while Bewick took over the text for the second volume. The book is admired mainly for the beauty and clarity of Bewick's wood engravings, which are widely considered his finest work, and among the finest in that medium.

British Birds has been compared to works of poetry and literature. It plays a recurring role in Charlotte Brontë's novel Jane Eyre. William Wordsworth praised Bewick in the first lines of his poem "The Two Thieves": "Oh now that the genius of Bewick were mine, And the skill which he learned on the banks of the Tyne."

The book was effectively the first "field guide" for non-specialists. Bewick provides an accurate illustration of each species, from life if possible, or from skins. The common and scientific name(s) are listed, citing the naming authorities. The bird is described, with its distribution and behaviour, often with extensive quotations from printed sources or correspondents. Those who provided skins or information are acknowledged. The species are grouped into families such as "Of the Falcon", using the limited and conflicting scientific sources of the time. The families of land birds are further grouped into birds of prey, omnivorous birds, insectivorous birds, and granivorous birds, while the families of water birds are simply listed, with related families side by side.

Each species entry begins on a new page; any spaces at the ends of entries are filled with tail-pieces, small, often humorous woodcuts of country life. British Birds remains in print, and has attracted the attention of authors such as Jenny Uglow. Critics note Bewick's skill as a naturalist as well as an engraver.

Approach

The preface states that "while one of the editors [Thomas Bewick] of this work was engaged in preparing the cuts, which are faithfully drawn from Nature, and engraved upon wood, the compilation of the descriptions .. (of the Land Birds) was undertaken by the other [Ralph Beilby],[1] subject, however, to the corrections of his friend, whose habits had led him to a more intimate acquaintance with this branch of Natural History", and goes on to mention that the compilation of text was the "production of those hours which could be spared from a laborious employment", namely the long hours of work engraving the minutely detailed wood printing blocks.[lower-alpha 1] What the preface does not say is the reason for this statement about the "editors", which was an angry stand-off between Bewick and Beilby, caused by Beilby's intention to have an introduction which merely thanked Bewick for his "assistance", and a title page naming Beilby as the sole author. Bewick's friend (and his wife's godfather) Thomas Hornby heard of this, and informed Bewick. An informal trade panel met to judge the matter, and the preface was the result; and Beilby's name did not appear on the title page.[3]

Each species of bird is presented in a few pages (generally between two and four; occasionally, as with the mallard or "Common Wild Duck", a few more). First is a woodcut of the bird, always either perched or standing on the ground, even in the case of water birds – such as the smew – that (as winter visitors) do not nest in Britain, and consequently are rarely seen away from water there.[4] Bewick then presents the name, with variations, and the Latin and French equivalents. For example, "The Musk Duck" is also named on the line below as "Cairo, Guinea, or Indian Duck", and the next line "(Anas moschata, Linn.—Le Canard Musque, Buff.)" provides the scholarly references to the giving of the Latin binomial by Linn[aeus] and a French description by Buff[on].[5]

The text begins by stating the size of the bird. Bewick then describes the bird, typically in one paragraph, naming any notable features such as the colour of the eyes ("irides"), the bill, the legs, and plumage on each part of the body. Next, the origin and distribution of the species are discussed, with notes or quotations from authorities such as John Ray, Gilbert White and Buffon.

Bewick then mentions any other facts of interest about the bird; in the case of the musk duck, this concerns its "musky smell, which arises from the liquor secreted in the glands on the rump". If the bird hybridizes with other species, this is described, along with whether the hybrids are fertile ("productive").

Finally, Bewick acknowledges anyone who helped. The musk duck is stated to have been drawn from a "living specimen" which was however "excepting the head, entirely white", unlike the "general appearance" shown in the woodcut; the bird "was lent to this work by William Losh, Esq., of Point Pleasant, near Newcastle". Losh, one of Bewick's many collaborators, was a wealthy partner in Losh, Wilson and Bell, manufacturers of chemicals and iron.[7] Many of the birds, especially the rarer species, were necessarily illustrated from skins rather than from life. For example, for the Sabine's snipe, "The author was favoured by N. A. Vigors, Esq., [who had described the supposed species] with a preserved specimen, from which the above figure is taken."[lower-alpha 2] In A Memoir (posthumously published in 1862), Bewick states that he intended to "stick to nature as closely as I could", but admits that he had "in several cases" to rely on the stuffed "preserved skins" of his neighbour Richard Routledge Wingate.[10][11]

The grouping of species gave Bewick difficulty,[12] as the scientific sources of the time did not agree on how to arrange the species in families, or on a sequence or grouping of those families. Bewick for example uses family groups like "Of the Falcon", in which he includes buzzards and sparrowhawks as well as what are now called falcons. The families of land birds are further grouped into birds of prey, omnivorous birds, insectivorous birds, and granivorous birds, while the families of water birds are simply listed, with what seemed to be related families, such as "Of the Anas" (ducks) and "Of the Mergus" (sawbill ducks), side by side.

In this way the book takes the form of, and sets a precedent for, modern field guides.[4][13] Indeed, the French naturalist François Holandre (1753–1830) assembled a field guide using Bewick's woodcuts as early as 1800.[14]

Each account is closed with a miniature woodcut known from its position in the text as a tail-piece.[15] These small artworks depict aspects of country life, often with humorous subjects, but all with Bewick's eye for detail, style, and precision.[16] Some add to the illustration of the bird in question, as for example the heron, where the tail-piece shows one heron catching an eel, and another flying away. The tail-piece for Sabine's snipe, a gamebird, shows a hunter firing, and a small bird falling to the ground. There is no exclusion of human life from the images: one tail-piece depicts a works complete with smoking chimney beside a river.[lower-alpha 3]

Outline

Land birds

The first volume "containing the History and Description of Land Birds" begins with a preface, an introduction, and a list of technical terms illustrated with Bewick's woodcuts. The introduction begins:

In no part of the animal creation are the wisdom, the goodness, and the bounty of Providence displayed in a more lively manner than in the structure, formation, and various endowments of the feathered tribes.

The birds are divided into granivorous (grain eating) and carnivorous groups, which are explained in some detail. The speed, senses, flight, migration, pairing behaviour and feeding of birds are then discussed, with observations from Spallanzani and Gilbert White, whose Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne was published in 1789. The pleasure of watching birds is mentioned:

To the practical ornithologist there arises a considerable gratification in being able to ascertain the distinguishing characters of birds as they appear at a distance, whether at rest, or during their flight; for not only every genus has something peculiar to itself, but each species has its own appropriate marks, by which a judicious observer may discriminate almost with certainty.[18]

Bewick also mentions conservation, in the context of the probable local extinction of a valuable resource:

"Both this and the Great Bustard are excellent eating, and would well repay the trouble of domestication; indeed, it seems surprising, that we should suffer these fine birds to be in danger of total extinction,[lower-alpha 4] although, if properly cultivated, they might afford as excellent a repast as our own domestic poultry, or even as the Turkey, for which we are indebted to distant countries.[20]"

The 1847 edition, revised with additional woodcuts and descriptions, is organized as follows, with the species grouped into families such as the shrikes:

- Birds of Prey

- Of the Falcon (includes buzzard, sparrowhawk)

- Of the Owl

- Omnivorous Birds

- Insectivorous Birds

- Of the Shrike

- Of the Flycatchers

- Of the Warblers

- Of the Wagtail

- Granivorous Birds

- Of the Lark

- Of the Titmouse

- Of the Bunting

- Of the Finch

- Of the Woodpecker

- Of the Swallow

- Of the Gallinaceous kind (gamebirds)

- Of the Grouse

- Of the Bustard

Water birds

The second volume "containing the History and Description of Water Birds" begins with its own preface, and its own introduction. Bewick discusses the question of where many seabirds go to breed, revisits the subject of migration, and concludes with reflections on "an all-wise Providence" as shown in Nature.

The 1847 edition is organized as follows:[lower-alpha 5]

- Of the Oyster Catcher

- Of the Plover

- Of the Heron

- Of the Avoset (1 sp.)

- Of the Spoonbill (1 sp.)

- Of the Ibis (1 sp.)

- Of the Curlew

- Of the Sandpiper

- Of the Godwit

- Of the Snipe

- Of the Rail

- Of the Gallinule

- Of the Coot

- Of the Phalarope

- Of the Grebes

- Of the Terns

- Of the Gull

- Of the Predatory Gulls (the skuas)

- Of the Petrel

- Of the Anas (ducks, geese and swans)

- Of the Mergus (sawbill ducks)

- Of the Cormorant

- Of the Gannet (1 sp.)

- Of the Divers

- Of the Guillemot

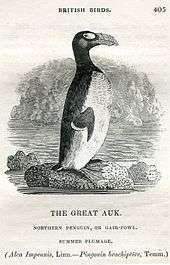

- Of the Auk

- Foreign Birds

The 'foreign birds' are not grouped but just listed directly as species, from Bearded Vulture to Mino. Fifteen birds are included, with no description, and despite their placement in the table of contents, they appear at the front of the volume as an 'Appendix'.

Reception

In 1805, the British Critic wrote that it was "superfluous to expatiate much on the merits of a work" that everyone liked because of "the aptness of its descriptions, the accuracy of its figures, the spirit of its wood engravings, and the ingenious variety of its vignettes."[21]

The 1829 Magazine of Natural History commented that "Montagu's Ornithological Dictionary and Bewick's Birds .. have rendered [the] department of natural history popular throughout the land".[22]

Ibis, reviewing the Memoir of Thomas Bewick, written by himself in 1862, compares the effect of Bewick and Gilbert White, writing "It was the pages of Gilbert White and the woodcuts of Bewick which first beguiled the English schoolboy to the observation of our feathered friends", and "how few of our living naturalists but must gratefully acknowledge their early debt to White's 'History' and to the life-like woodcuts of Bewick!" The reviewer judges that "Probably we shall not wrong the cultivated annalist of Selborne by giving the first place to Bewick." However, comparing them as people, "Bewick has not the slightest claim to rank with Gilbert White as a naturalist. White was what Bewick never was, a man of science; but, if no naturalist, Bewick was a lover of nature, a careful observer, and a faithful copier of her ever-varying forms. In this, and in this alone, lies his charm."[23]

The 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica's entry on Thomas Bewick describes "the British Birds" as "his great achievement, that with which his name is inseparably associated", observing that "Bewick, from his intimate knowledge of the habits of animals acquired during his constant excursions into the country, was thoroughly qualified to do justice to this great task."[24]

British Birds, reviewing a "lavishly illustrated" British Library book on Bewick, writes that "No ornithologist will ever regard Thomas Bewick, known primarily for The History of British Birds (1797–1804), as a naturalist of the same standing as contemporaries such as Edward Donovan, John Latham and James Bolton", noting however that Bewick helped to define "a certain English Romantic sensibility". More directly, the review notes that "Bewick was aware that his role was to offer a modest guide to birds that the common man not only could afford but would also want to possess." Bewick was not "a scientist, but he was a perfectionist". The book's text was written by "failed author" Ralph Beilby, but the text is "almost extraneous" given Bewick's masterpiece.[1]

The Tate Gallery writes that Bewick's " best illustrations ... are in his natural history books. The History of British Birds (2 vols, Newcastle upon Tyne, 1797–1804) reveals Bewick's gifts as a naturalist as well as an engraver (the artist was responsible for the text as well as the illustrations in the second volume)." The article notes that the book makes "extensive use of narrative tailpieces: vignettes in which manifold aspects of north-country life are expressed with affection, humour and a genuine love of nature. In later years these miniature scenes came to be more highly regarded than the figures they accompany."[16]

Dissenting from the general tone of praise for Bewick, Jacob Kainen cites claims that "many of the best tailpieces in the History of British birds were drawn by Robert Johnson", and that "the greater number of those contained in the second volume were engraved by Clennell. Granted that the outlook and the engraving style were Bewick's, and that these were notable contributions, the fact that the results were so close to his own points more to an effective method of illustration than to the outpourings of genius." Kainen argues that while competent, Bewick "was no Holbein, no Botticelli—it is absurd to think of him in such terms—but he did develop a fresh method of handling wood engraving."[25]

The Linnean Society writes that the History "shows that he was also an excellent naturalist, a meticulous observer of birds and animals in their habitats."[26]

The University of Maryland writes that "The Birds is specific to those species indigenous to Britain and is incredibly accurate due to Bewick's personal knowledge of the habits of birds in the wild acquired during his frequent bird-watching expeditions." It adds that "Bewick's woodcarvings are considered a pinnacle example of the medium."[27]

Jenny Uglow, writing in The Guardian, notes that "An added delight was the way he filled the blank spaces with 'tail-pieces', tiny, witty, vivid scenes of ordinary life." She describes the importance of Birds in Jane Eyre, and ends "He worked with precision and insight, in a way that we associate with poets such as Clare and Wordsworth, Gerard Manley Hopkins and Elizabeth Bishop. To Bewick, nature was the source of joy, challenge and perpetual consolation. In his woodcuts of birds and animals as well as his brilliant tail-pieces, we can still feel this today."[15] However, in her biography of Bewick, she adds that "The country might be beautiful but it also stank: in his vignettes men relieve themselves in hedges and ruins, a woman holds her nose as she walks between the cowpats, and a farmyard privy shows that men are as filthy as the pigs they despise."[28]

Hilary Spurling, reviewing Uglow's biography of Bewick in The Observer, writes that when Birds appeared, people all over Britain "became his pupils". Spurling cites Charles Kingsley's story of his father's hunting friends from the New Forest mocking him for buying "a book 'about dicky-birds", until, astonished, they saw the book and discovered "things they had known all their lives and never even noticed".[29]

John Brewer, writing in the London Review of Books, says that for his Birds, "Bewick had acquired national renown as the artist who most truthfully depicted the flora and fauna of the British countryside." He adds that "Bewick's achievement was both technical and aesthetic." In his view, Bewick "reconciled nature, science and art. His engravings of British birds, which represent his work at its finest, are almost all rendered with the precision of the ornithologist: but they also portray the animals in their natural habitat – the grouse shelters in his covert, the green woodpecker perches on a gnarled branch, waders strut by streams ..." He observes that "Most of the best engravings include a figure, incident or building which draws the viewer's eye beyond and behind the animal profile in the foreground. Thus the ploughboy in the distant field pulls our gaze past the yellow wagtail ..."[30]

In culture

The History is repeatedly mentioned in Charlotte Brontë's 1847 novel Jane Eyre. John Reed throws the History of British Birds at Jane when she is ten; Jane uses the book as a place to which to escape, away from the painful Reed household; and Jane also bases her artwork on Bewick's illustrations. Jane and Mr Rochester use bird names for each other, including linnet, dove, skylark, eagle, and falcon. Brontë has Jane Eyre explain and quote Bewick:[15][31]

I returned to my book--Bewick's History of British Birds: the letterpress thereof I cared little for, generally speaking; and yet there were certain introductory pages that, child as I was, I could not pass quite as a blank. They were those which treat of the haunts of sea-fowl; of 'the solitary rocks and promontories' by them only inhabited; of the coast of Norway, studded with isles from its southern extremity, the Lindeness, or Naze, to the North Cape--[32]

Where the Northern Ocean, in vast whirls,

Boils round the naked, melancholy isles

Of farthest Thule; and the Atlantic surge

Pours in among the stormy Hebrides.[1][a]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

JaneEyrewas invoked but never defined (see the help page).

Cite error: There are<ref group=lower-alpha>tags or{{efn}}templates on this page, but the references will not show without a{{reflist|group=lower-alpha}}template or{{notelist}}template (see the help page).

The English romantic poet William Wordsworth began his 1800 poem The Two Thieves; or, the Last Stage of Avarice with the lines[33][34]

Oh now that the genius of Bewick were mine

And the skill which he learned on the banks of the Tyne.

Then the Muses might deal with me just as they chose,

For I'd take my last leave both of verse and of prose.[1]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

WWpoemwas invoked but never defined (see the help page).

Peter Hall's 1974 film Akenfield (from the 1969 book by Ronald Blythe) contains a scene where the grandfather as a young man is reaping a cornfield. He weeps when he accidentally crushes a bird's egg, an image derived from Bewick's tail-piece woodcut for the partridge. The woodcut shows a reaper with a scythe, a dead bird and its nest of a dozen eggs on the ground under the scythe, which has just lifted. George Ewart Evans used the image on the title page of his 1956 book about Blaxhall (near Charsfield, on which 'Akenfield' is probably partly based).

Tail-pieces

A selection of tail-pieces from the book, where they have no captions.

-

Children in runaway cart

-

Women collecting shellfish

-

Hunter precariously retrieving duck from river

-

Old woman with ducks

-

Toy boats in river

-

Hunter in the snow[a]

-

That pisseth against a wall

-

Pegleg and peacock

- ^ Uglow, 2006. pp. 137–138.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

Principal editions

Volume 1 first appeared in 1797, and was reprinted several times in 1797, then again in 1798 and 1800. Volume 1 was priced 13s. in boards. Volume 2 first appeared in 1804 (price 11. 4s. in boards). The first imprint was "Newcastle : Printed by Sol. Hodgson, for Beilby & Bewick; London: Sold by them, and G.C. and J. Robinson, 1797–1804." The book was reprinted in 1805, 1809, 1816, and 1817.[36]

In 1821 a new edition appeared with supplements to both volumes and additional figures, with the imprint "Printed by Edward Walker, Pilgrim-Street, for T. Bewick: sold by him, and E. Charnley, Newcastle; and Longman and co., London, 1821." The book was reprinted in many subsequent versions with a 6th edition in 1826, another in 1832, an 8th edition in 1847, and a royal octavo 'Memorial Edition' in 1885.[36]

- A History of British Birds. First Edition.

- --- Bewick, Thomas; Beilby, Ralph (1797). Volume 1, Land Birds.

- --- Bewick, Thomas (1804). Volume 2, Water Birds.

Selected modern versions

- Bewick's British Birds (2010), Arcturus. (hardback) ISBN 978-1-84837-647-2

- Bewick, Thomas; Aesop; Bewick, Jane (2012). Memorial Edition Of Thomas Bewick's Works: A History Of British Birds. (reproduced in original format) Ulan Press.

Notes

- ↑ Bewick had a "strained" relationship with Beilby, who was first his tutor, then from 1777 his business partner. They produced A General History of Quadrupeds together in 1790, but after Land Birds in 1797 and "a period of dissatisfaction" they separated.[2]

- ↑ The "Sabine's snipe" species described by Vigors was treated as a common snipe by Barrett-Hamilton in 1895[8] and by Meinertzhagen in 1926, but was thought to be probably a Wilson's snipe in 1945. The skin that Bewick worked from was presumably Vigors' type specimen; it was much darker than a typical common snipe.[9]

- ↑ Bewick made dozens of woodcuts for coal certificates for collieries near Newcastle, in what is now Tyne and Wear. These depict buildings such as the Custom House with its smoking chimneys,[17] and one woodcut is boldly headed 'NEWCASTLE'.[2]

- ↑ Bewick's prediction was correct. The great bustard became extinct in Britain in the 1830s.[19]

- ↑ Some of the species in the book appear without any section heading.

References

- 1 2 "Thomas Bewick: the complete illustrative work, by Nigel Tattersfield". British Birds. 9 April 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- 1 2 "The Bewick Collection: About Thomas Bewick". Newcastle Collection. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ↑ Uglow, 2006. pp. 259–261.

- 1 2 Svensson, Lars (text, maps); Mullarney, Killian and Zetterström, Dan (plates, captions); Grant, Peter J. (2009). Collins Bird Guide 2nd Edition. Collins. p. 42.

- ↑ Bewick, 1797–1804.

- ↑ Vigors, NA (May 1825). "XXVI. A Description of a new Species of Scolopax lately discovered in the British Islands: with Observations on the Anas glocitans of Pallas, and a Description of the Female of that Species.". Transactions of the Linnean Society of London 14 (3): 556–562. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1823.tb00102.x.

- ↑ "Low Fell – Additional Pages". Low Fell History: Part 1. Gateshead Libraries. 2011. Retrieved 21 March 2012.

- ↑ Barrett-Hamilton, GEH (January 1895). "Sabine's Snipe. Gallinago Coelestis, var. Sabinii" (PDF). The Irish Naturalist 4 (1): 12–17.

- ↑ "General Notes" (PDF). The Wilson Bulletin 57 (1): 75–76. March 1945.

- ↑ Bewick, Thomas (1979) [1862]. A Memoir. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Sly, Debbie (2005). "'With skirmish and capricious passagings': ornithological and poetic discourse in the nightingale poems of Coleridge and Clare" (PDF). University of Worcester. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- ↑ Uglow, 2006. p. 249.

- ↑ Bate, Jonathan (15 August 2004). "A bird in the bush is always best". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- ↑ Jordan, Mary. "Searching the Skies, Searching the Stacks: Bird Field Guides in the Watkinson Library" (PDF). 2011. Trinity College, Hartford, Connecticut. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 Uglow, Jenny (14 October 2006). "The Guardian". Small wonders. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- 1 2 "Thomas Bewick 1753–1828". Tate Gallery. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ↑ "The Bewick Collection (Pease Bequest): Coal certificates - Tyne". Newcastle Collection. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ↑ Bewick, volume 1, Land Birds, 1847 edition. "Introduction".

- ↑ Cooper, Joanne (2013). "Otis tarda (great bustard)". Natural History Museum. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ↑ Bewick, volume 1, Land Birds, 2nd edition, 1847. "Little Bustard".

- ↑ Anon (1805). "A History of British Birds by Thomas Bewick". British Critic 26: 292–297.

- ↑ Loudon, John Claudius; Charlesworth, Edward; Denson, John (1829). Magazine of natural history. printed for Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green. pp. 360–364.

- ↑ Anon (October 1862). "Review of the recently published Memoir of Bewick". Ibis 4 (4): 368–378. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1862.tb07513.x.

- ↑ 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica: Bewick, Thomas

- ↑ Kainen, Jacob (1959). "Why Bewick Succeeded: A Note in the History of Wood Engraving". Smithsonian Institution United States National Museum Bulletin 218: 185–201.

- ↑ "Thomas Bewick, Engraver and Naturalist". Linnean Society. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ↑ "Thomas Bewick". University of Maryland. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ↑ Uglow, 2006. p. 314.

- ↑ Spurling, Hilary (24 September 2006). "The Observer". All about the birds and the bees. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ↑ Brewer, John (18 March 1982). "Progressive Agenda". London Review of Books 4 (5): 18–19.

- ↑ Taylor, Susan B. (March 2002). "Image and Text in Jane Eyre's avian vignettes and Bewick's History of British Birds.".

- ↑ Brontë, Charlotte (1847). "1". Jane Eyre. Smith, Elder & Co.

- ↑ "The Two Thieves; or, the Last Stage of Avarice". Bartleby.com. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ↑ Gannon, Thomas C. (2009). Skylark Meets Meadowlark: Reimagining the Bird in British Romantic and Contemporary Native American Literature. University of Nebraska Press. p. 340.

- ↑ Bewick, 1847. Volume 2, page 406.

- 1 2 "'History of British birds : the figures engraved on wood'". WorldCat. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

Bibliography

- Bewick, Thomas (1797–1804). A History of British Birds. Newcastle: Beilby and Bewick.

- Uglow, Jenny (2009). Nature's Engraver: A Life of Thomas Bewick. University of Chicago Press.

External links

- The Bewick Society: Publications

- Newcastle Collection: Bewick

- The Folio Society

- Free Project Gutenberg ebook: Why Bewick Succeeded