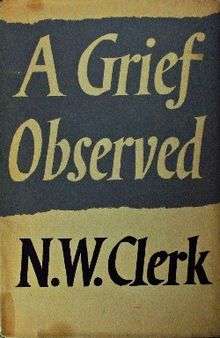

A Grief Observed

First edition | |

| Author | C. S. Lewis |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Published | 1961 (Faber and Faber) |

| Media type | Paperback |

| Pages | 160 |

A Grief Observed is a collection of C. S. Lewis's reflections on the experience of bereavement following the death of his wife, Joy Davidman, in 1960. The book was first published in 1961 under the pseudonym N.W. Clerk as Lewis wished to avoid identification as the author. Though republished in 1963 after his death under his own name, the text still refers to his wife as “H” (her first name, which she rarely used, was Helen).[1] The book is compiled from the four notebooks which Lewis used to vent and explore his grief. He illustrates the everyday trials of his life without Joy and explores fundamental questions of faith and theodicy. Lewis’s step-son (Joy’s son) Douglas Gresham points out in his 1994 introduction that the indefinite article 'a' in the title makes it clear that Lewis's grief is not the quintessential grief experience at the loss of a loved one, but one individual's perspective among countless others. The book helped inspire a 1985 television movie Shadowlands, as well as a 1993 film of the same name.

Summary

A Grief Observed explores the processes which the human brain and mind undergo over the course of grieving. The book questions the nature of grief, and whether or not returning to normalcy thereafter is even possible within the realm of human existence on earth. Based on a personal journal he kept, Lewis refers to his wife as "H" throughout this series of reflections, and reveals that she had died from cancer only three years after their marriage. The book is extremely candid, and it details the anger and bewilderment he had felt towards God after H's death, as well as his impressions of life without her. The period of his bereavement was marked by a process of moving in and out of various stages of grief and remembrance, and it becomes obvious that it heavily influenced his spirituality. In fact, Lewis ultimately comes to a revolutionary redefinition of his own characterisation of God: experiencing gratitude for having received and experienced the gift of a true love.

The book is divided into four parts, each headed with a Roman numeral, and each a collection of excerpts from his journals documenting scattered impressions and his continuously evolving state of mind.

Reactions

Lewis exhibits doubt and asks many fundamental questions of faith throughout the work. Because of his candid account of his grief and the doubts he voices, some of his admirers found it troubling. They were disinclined to believe that this Christian writer could be so close to despair. Some thought that it might be a work of fiction. Others, such as Lewis’s critics, suggested that he was wisest when he was overcome with despair.[2] When Lewis was first attempting to publish his manuscript, his literary agent, Spencer Curtis Brown, sent it to the publishing company Faber and Faber. One of the directors of the company at the time was T.S. Eliot, who found the book intensely moving.[3] Madeleine L’Engle, an American author best known for her young adult fiction, wrote a foreword for the 1989 printing of the book. In the forward, L’Engle speaks of her own grief after losing her husband and notes the similarities and differences. She makes a point similar to Douglas Gresham's— each grief is different even if they do bear similarities.[4]

A Grief Observed and The Problem of Pain

The book is often compared to another book by Lewis, The Problem of Pain, written approximately twenty years before A Grief Observed. The Problem of Pain seeks to provide theory behind the pain in the world. A Grief Observed is the reality of the theory in The Problem of Pain.[5] It was more difficult to apply the theories he posited to a pain with which he was so intimately involved. At first it is hard for Lewis to see the reason of his theories amidst the anguish of his wife's death but through the book one can see the gradual reacceptance of these theories, the reacceptance of the necessity of suffering.[2]

Lewis' difficulty is specifically reflected in the following passage from the book: "Is anything more certain than that in all those vast times and spaces, if I were allowed to search them, I should nowhere find her face, her voice, her touch? She died. She is dead. Is the word so difficult to learn?"[4] And Lewis' ultimate resolution of his dilemma is in part articulated in the book, as follows: "I will not, if I can help it, shin up either the feathery or the prickly tree. Two widely different convictions press more and more on my mind. One is that the Eternal Vet is even more inexorable and the possible operations even more painful than our severest imaginings can forebode. But the other, that 'all shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well'. "[4]

References

- ↑ Hooper, Walter. C.S. Lewis: A Companion and Guide. San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1996. Page 196. Print.

- 1 2 Talbot, Thomas. "A Grief Observed." The C.S. Lewis Reader's Encyclopedia. Ed. Jefferey D. Shultz, John G. West Jr. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan Publishing House, 1998. Print.

- ↑ Hooper. Page 194.

- 1 2 3 Lewis, C.S. A Grief Observed. New York: Harper & Row, 1961. Print.

- ↑ Walsh, Chad. The Literary Legacy of C.S. Lewis. New York: Hardcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1979. Page 238. Print.