Army Air Forces Antisubmarine Command

| Army Air Forces Antisubmarine Command | |

|---|---|

|

Emblem of I Bomber Command (1943-1946) | |

| Active | 1942-1946 |

| Country | United States |

| Branch | United States Army Air Forces |

| Type | Antisubmarine Warfare; Command and Control |

| Motto | Guard With Power |

The Army Air Forces Antisubmarine Command (AAFAC) was a direct reporting agency of the United States Army Air Forces during World War II. Its mission was to deal with Nazi Germany's U-boat threat.

History

Lineage

- Constituted as Army Air Forces Antisubmarine Command on 13 October 1942

- Activated on 15 October 1942

- Redesignated I Bomber Command 31 August 1943 and assigned to First Air Force

- Inactivated on 21 March 1946

- Disbanded on 8 October 1948

Assignments

- Headquarters, United States Army Air Forces, 15 October 1942

- First Air Force, 31 August 1943 – 21 March 1946

Stations

- 90 Church Street, New York City, New York, 15 October 1942

- Mitchel Field, New York, c. 1 October 1943 – 21 March 1946.

Units

Wing/Group

|

|

Squadron

The Command had twenty five Squadrons. Six were organized into two overseas groups and the balance into two Wings in the Americas.

- 4th Antisubmarine Squadron, 8 June-8 July 1943

- 6th Antisubmarine Squadron, 8 June-14 August 1943

- 13th Antisubmarine Squadron, 18 October-9 December 1942

- 17th Antisubmarine Squadron, 18 October-20 November 1942

- 19th Antisubmarine Squadron, 8 June-11 July 1943

- 20th Antisubmarine Squadron, 8 February-13 October 1943

- 22d Antisubmarine Squadron, 3–8 March 1943

Aircraft

Antisubmarine Command's units flew such aircraft as Douglas B-18 Bolo, Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, Consolidated B-24, North American B-25 Mitchell, Lockheed B-34 Ventura, North American O-47, O-52, Douglas A-20 Havoc, and the Lockheed A-29 Hudson.

Operations

Origins

The USAAF began flying antisubmarine patrols along the Atlantic coast immediately after the Pearl Harbor Attack. Initial patrols over the approaches to New York harbor were flown by First Air Force, I Bomber Command from Mitchel Field. Patrols over Boston were flown from Otis Field. However, despite the Battle of the Atlantic raging for the previous two years, the United States was not prepared for war against U-Boats. The United States lacked ships, aircraft, equipment, trained personnel, and a master plan to counter any serious submarine offensive.

The Navy's air arm in 1941 was as inadequate as its anti-submarine surface fleet. Initially, the Navy had no escort carriers, a type that eventually was very effective against the German submarines. It also lacked aircraft capable of long range patrols over the ocean to attack submarines when sighted. Prewar plans called for the AAF to support naval forces in case of an emergency. To supplement its meager anti submarine forces, the Navy turned to the AAF. Since 1938, however, the Air Corps/Army Air Forces had been restricted from conducting overwater operations beyond a 100-mile limit, and the AAF had no equipment or trained personnel for the specialized job of patrolling against, detecting, and attacking submarines from the air.

Also, the sudden entry of the United States into World War II caught Kriegsmarine Admiral Doenitz by surprise, with no submarines immediately available to send to American coastal waters. Doenitz quickly allocated five long distance submarines, all he could quickly make ready, to Operation DRUMBEAT, his code name for operations against shipping in U.S. coastal sea lanes. These sailed from Lorient, France, between 23 and 27 December 1941.

On 31 December 1941 a Coast Guard cutter reported a periscope in Portland Channel, and on 7 January 1942 an Army plane sighted a submarine off the coast of New Jersey. On that same day the Navy reported the presence of a fleet of U-boats in the waters south of Newfoundland. The British merchant ship SS Cyclops was sunk off Nova Scotia on 11 January, 125 miles south-east of Cape Sable. Cyclops was the first ship sunk in the German U-boat campaign against the East Coast of North America. Three days later the tanker Norness went down southeast of Nontauk Point, Long Island.

These sinkings of merchant vessels along the Atlantic coast made it clear to the American public the grim realities of war. These attacks on commercial shipping were not only a drain on supply lines of our British Allies, which was perilously thin at best, but the attacks virtually on our Atlantic seaboard threatened the coastal commerce as well. In the remaining days of January 1942, 13 more ships were sunk by U-Boats off the Northeast Atlantic coast.

War had arrived in the territorial waters of the United States.

I Bomber Command

As soon as the news of Pearl Harbor arrived, the Commander of the North Atlantic Naval Coastal Frontier requested the Commanding General of the Eastern Defense Command to undertake offshore patrols with all available aircraft. To meet the emergency developing along the northeast coast, the Army and Navy agreed to pool their resources in response to the U-Boat threat. However, the Air Force leadership considered its role in anti submarine war to be temporary, and the major thrust of its efforts remained strategic bombing. Thus the AAF somewhat reluctantly began flying anti submarine missions.

For nearly 10 months I Bomber Command bore the brunt of the air war along the Atlantic coast against the U-boats. However, the aircraft assembled by First Air Force were approximately 100 two-engine aircraft of various sizes and types largely obsolete. It was, however, all that could be made available.

The Germans between mid-January 1942 and the end of June sank 171 ships off the East Coast, many of them tankers. During the first half of 1942, the Allies lost three million tons of shipping, mostly in American waters. The submarine attacks claimed about 5,000 lives, and the loss of irreplaceable cargoes grievously endangered Great Britain's ability to continue the war.

The Air Force I Air Support Command dispatched observation and pursuit (fighter) aircraft on patrol out to 40 miles (64 km) offshore from Portland, Maine, south to Wilmington, North Carolina, but usually had fewer than ten aircraft per day on patrol. I Bomber Command relied on its medium B-25 Mitchell and B-18 Bolo bombers to fly up to 300 miles offshore and its heavy B-17 Flying Fortress's to cover up to 600 miles out. On the average, I Bomber Command had only three aircraft flying each day from Westover Field, Massachusetts, and three from Mitchel Field, New York, not nearly enough to patrol the Naval Eastern Sea Frontier effectively. The aircraft used against the U-boats by First Air Force were generally unsuited for antisubmarine missions. All, with the exception of a squadron of B-17's, were of relatively short range and limited carrying capacity. And all, of course, as yet lacked special detection equipment such as RADAR. The old B-18, though obsolescent, proved to be the most useful in the early months, but even they were at first scarce.

The AAF obtained the assistance of the Civil Air Patrol (CAP) to augment I Bomber Command's efforts. Organized a week before the war began, CAP consisted of civilian pilots willing to fly their own aircraft off the coast to look for submarines and to assist in the rescue of survivors. Receiving only aviation gasoline from the AAF, CAP began patrolling on 8 March 1942, eventually establishing 21 stations from Bar Harbor, Maine, to Brownsville, Texas. With the help of CAP, the I Bomber Command flew almost 8,000 hours in March 1942, about as much as in January and February combined. The additional patrols forced German submarines to remain submerged except on the darkest nights.

Most of the I Bomber Command units involved in the antisubmarine war in early 1942 were still in a training status, and those best trained had been taken away for service in the Southwest Pacific or being prepared for deployment to England. In addition, prewar agreements had assigned overwater operations to the Navy and had placed restrictions on Army overwater flying. So it is scarcely surprising that the Army planes entered on their adopted task with demolition bombs instead of depth charges and with crews who were ill-trained in naval identification or in the best method of attacking submarines.

The United States sought the guidance of Great Britain, which had been waging anti submarine war against Germany since 1939. As suggested by the British, the AAF and the U.S. Navy established a Joint Control and Information Center in New York City on 31 December 1941. The center tracked the movements of merchant shipping, plotted enemy contacts, and determined the locations of all surface and air anti submarine patrols. However, the two services worked independently in different parts of the same building, each maintaining its own situation plot and receiving intelligence from different sources.

The situation led to the Navy failing to send the information it did receive from the British to I Bomber Command, and the intelligence received not being used in operations against the U-Boats. Even if it were disseminated, intelligence data often lost its usefulness because it was not quickly communicated from Navy to Army organizations or down the chain of command in either service. In large part, this lapse was the result of the chaos and confusion that Army and Navy commands suffered in the first few months of the war. This confusion also led to faulty tactics that usually resulted in unsuccessful attacks on enemy submarines. Attacked submarines often escaped because the aerial and surface attacks were sporadic rather than sustained. Through inexperience, poor training, and lack of adequate forces, both Navy surface forces and AAF air crews often failed to follow up initial anti submarine attacks.

As the weeks passed, however, the situation began to improve. Air Force planes began to be equipped with depth charges instead of bombs, and primitive RADAR equipment was fitted to the long distance bombers. Training in over water navigation, along with ship recognition took place along with training from the British in anti-submarine attack tactics took place. There was some early success by I Bomber Command. Constant aerial patrolling to as far as 600 miles out to sea restricted opportunities for submarines to operate on the surface.

Until the first AAF aircraft received RADAR sets in March 1942, the submarines could surface and attack almost at will during dark nights or inclement weather, but the advent of night flights using RADAR to locate surfaced submarines added considerably to the value of the routine anti submarine air patrol. By June 1942, I Bomber Command aircraft had vastly increased sightings of and attacks on German submarines. The first successful AAF aircraft attack on a German submarine occurred on 7 July 1942, when a Lockheed A-29 Hudson of the 396th Bombardment Squadron attacked a submarine (U-701) seven miles from Cherry Point, North Carolina. According to the after-action report the aircrew "attacked from 50 feet (15 m) at 220 miles per hour (354 km/h), releasing three MK XVII depth charges in train about 20 seconds after the target submerged. The submarine was still visible underwater as the bombs fell. The first hit short of the stem; the second, just aft of the conning tower; the third, just forward of the conning tower. Fifteen seconds after the explosions, large quantities of air came to the surface, followed by 17 members of the crew."

By the spring of 1942, I Bomber Command was waging full-scale antisubmarine warfare, yet it was still theoretically acting in an emergency capacity in support of Naval forces, and its units might at any time be withdrawn to their normal duties of bombardment. The fact was that in 1942, Air Force units were sorely needed in the Southwest Pacific, and Eighth Air Force was building up its forces in England. Both the Pacific as well as European theaters needed every combat aircraft they could find as the means for large-scale production of aircraft had not yet been developed. Also, the antisubmarine patrols was seen by Air Force leaders as a secondary mission.

Also, no system of unified command between the Army Air Forces and the Navy had been set up specifically for joint operations peculiar to antisubmarine warfare. Units of the Army Air Force had been effectively discouraged by the Navy from undertaking practice reconnaissance flights over water beyond the 100-mile limit. Cooperation at the higher levels of the AAF and the Navy was elusive, partly because of historical rivalry. Between World Wars I and II, the two services had argued bitterly over the roles of their respective air arms, the Navy insisting on responsibility for all missions over the ocean and the Army insisting on controlling all long range, land based aircraft. The jurisdictional problem continued into the war and at times handicapped efforts to counter enemy submarine attacks in American waters.

AAF Commanding General Henry H. Arnold proposed to settle the question in a practical compromise. In a letter to Admiral Ernest King, Chief of Naval Operations, on 9 March 1942, he wrote: "To meet the present situation, I propose to recommend the establishment of a Coastal Command, within the Army Air Corps which will have for its purpose operations similar to the Coastal Command, RAF," operating "when necessary under the control of the proper Naval authority". The virtues of such an organization would, Arnold believed, be many. It would not only do the job, it would also have the flexibility necessary for antisubmarine action, and could readily be decreased as the need decreased, the units then simply reverting to normal bombardment duty without becoming stranded wastefully in a naval program which left no place for them.

In this proposal Arnold pointed the way to the settlement finally adopted in the creation of the Army Air Forces Antisubmarine Command.

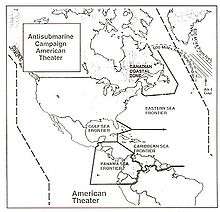

Gulf and Caribbean operations

- See Also: Antilles Air Command

.jpg)

Another issue was the of the German U-Boat campaign in American waters had spread south to the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea. In addition to the Atlantic coast, where Admiral Doenitz kept about 4 or 5 submarines on patrol, Doenitz deployed several U-Boats into the Gulf and Caribbean for operations. On 16 February, a German submarine sank two tankers off San Nicholas, Aruba, then moved into the harbor and shelled a refinery, inflicting little damage but killing four people. In February and March, the Germans operated six submarines in the Caribbean Sea, each patrolling for two to three weeks before returning to France.

The situation in the Gulf and Caribbean areas had become so serious that General Arnold requested the Third Air Force to use its units for antisubmarine patrol during their regular training missions flying over the Gulf. This shift of the German submarine offensive to the Gulf overwhelmed the resources of the Navy and the AAF. AAF antisubmarine operations had begun in December 1941 with operations from four states only, from Bangor, Maine, to Langley Field, Virginia. By September 1942 AAF antisubmarine patrols were operating in seven states, from Westover Field, Massachusetts to Galveston, Texas, stretching the limits of First and Third Air Forces to accommodate the antisubmarine mission which was barely adequate to defend against submarines along the Atlantic coast. In addition the commands also were charged with the important training mission of forces to be deployed overseas into the combat theaters.

The AAF, fearing a German or Japanese attack on the Panama Canal transferred to Sixth Air Force 80 additional fighter aircraft, nine heavy bombers, and four mobile radar sets. In February 1942, Sixth Air Force assumed responsibility for the aerial defense of the Panama Canal. Then in April 1942, when the German submarine threat became evident, Sixth Air Force, cooperating with the Navy, instituted anti submarine patrol flights as far east as Curaçao. Most flights were by tactical aircraft, such as Bell P-39 Airacobra’s and Northrup A-17A Nomad's, which could fly only during daylight; lacking radar and trained observers, the pilots had little luck in spotting enemy submarines. On the other hand, Sixth Air Force aircraft occasionally attacked friendly ships and submarines, fortunately without damaging them.

The AAF in February 1942 organized a provisional force, designated the Antilles Air Task Force under Sixth Air Force, headquartered at Borinquen Air Base, Puetro Rico. The Task Force (later Command) operated from scattered airfields throughout the Caribbean at Trinidad, Curaçao, Aruba, Saint Lucia, Surinam, British Guiana, Puerto Rico, Saint Croix, and Antigua. Initially it consisted of about 40 B-18 medium bombers, seven Douglas A-20 Havoc light bombers, and various fighter aircraft (P-39s, P-40s). The task force obtained radar equipped aircraft, which vastly increased its anti submarine capability. Prior to July the air crews reported few sightings of or attacks on submarines, but in July and August attacked 20. To supplement these efforts, First Air Force sent six B-18's equipped with radar to the Caribbean. Detachments of B-18's stationed at Trinidad, Curaçao, Dutch Guyana, and British Guyana began operations in June 1942, but these aircraft, lacking radar, could not stem the German efforts in the area during the summer.

AAF Antisubmarine Command

- See Also: 1st Search Attack Group

On 22 September 1942 the AAF began to organize the Army Air Forces Antisubmarine Command (AAFAC), using the personnel and equipment of I Bomber Command as its core for combat units, personnel and aircraft. The First Air Force had been engaged in anti submarine war for almost a year. During that time it had laid the basis for an effective organization and made plans for a larger anti submarine force. The new AAFAC was constituted on 13 October and activated on 15 October. Simultaneously, I Bomber Command was inactivated the same day and transferred to the Second Air Force.

The principal mission of AAFAC was to be "the location and destruction of hostile submarines wherever they may be operating". As a necessary means to this end it had the secondary mission of training crews and developing devices and techniques. The command was a direct reporting agency to the Commanding General, United States Army Air Forces, although its operations on the United States Navy Eastern and Gulf Sea Frontiers were to be conducted under the tactical control of Naval officials. The former I Bomber Command furnished the units, personnel, aircraft, and equipment for the new organization. By 20 November 1942, the AAFAC had organized the squadrons it had inherited from I Bomber Command into the 25th and 26th antisubmarine Wings with headquarters at New York and Miami respectively.

Initially, AAFAC had 19 operational antisubmarine Squadrons and only 20 B-24 Liberators, the aircraft type most useful for long range anti-submarine patrolling. The command grew rapidly until, by September 1943, there were 25 antisubmarine squadrons, most being equipped with B-24's specially modified for antisubmarine warfare. AAFAC squadrons were eventually located in the Americas from Newfoundland south to Brazil, and in Europe, based in Dorset, England, and French Morocco, with operating units as far east as Tunisia.

With the increasing number of RADAR-equipped B-24s over the Atlantic coastline and Gulf, the Germans found the hunting more profitable in the area of Trinidad until mid 1943. AAFAC consequently based B-18 Bolos s at Edinburgh Field, Trinidad, from early January until August 1943. In November and December 1942, German submarines sank 18 ships. Increased aerial patrols paid off with no losses of friendly ships near Trinidad from January to July 1943. During this time, the AAF B-18's engaged mostly in convoy escort and coverage missions. In July–August, German submarines sank four merchant vessels. The AAF anti submarine squadrons, flying both B-24's and B-18's, made six attacks and participated in two killer hunts to foil the enemy offensive in Trinidad waters.

In addition to the Trinidad area, the German submarines operated extensively in the South Atlantic Ocean in 1943, where merchant vessels sailed independently because there was no convoy system. AAFAC sent a detachment of B-24 aircraft in May from Trinidad to Natal, Brazil, to patrol the South Atlantic sea lanes at ranges beyond the reach of the Brazilian Air Force and flew patrols over the South Atlantic Ocean until August 1943.

In October 1941, far to the north, an Air Force detachment of four to six B-17 Flying Fortresses had begun anti submarine patrols over the northwest Atlantic Ocean from RCAF Station Gander, Newfoundland. The B-17's were armed with machine guns and bombs but carried no RADAR or depth charges. In July 1942, the 421st Bombardment Squadron (Heavy), also flying B-17's and with a primary mission of long range bombardment training, replaced the detachment. The squadron cooperated with Royal Canadian Air Force and United States Navy organizations in Newfoundland to carry on its secondary mission of anti submarine war. Then, in the fall of 1942, AAFAC made anti submarine patrol the squadron's primary mission, redesignating it the 20th Antisubmarine Squadron (Heavy).

During the 1943 Allied Conference in Casablanca, French Morocco, the United Kingdom and the United States agreed to deploy B-24 aircraft to patrol the mid Atlantic gap. Modified B-24's, with a radius up to 1,000 miles (1,609 km), could fly day or night in all but the worst weather to detect and attack submarines. The British immediately began operating Liberators, the Royal Air Force designation of the B-24, from bases in Ireland and Iceland to cover the eastern part of the gap, but the U.S. Navy did not send any aircraft to cover the western stretches of the mid Atlantic. During February 1943 21 ships totaling almost 200,000 tons were lost, mostly in the western gap. The next month in the Atlantic, the Allies lost 38 ships of 750,000 tons and an escort in four convoys.

On 18 March a B-24 detachment of the 25th Antisubmarine Wing established a headquarters at St. John's, Newfoundland, and began anti submarine patrols on 3 April 1943. By the end of the month AAFAC had three B-24 squadrons operating from RCAF Station Torbay and RCAF Gander in Newfoundland. The squadrons engaged in convoy coverage and in broad offensive sweeps ahead of the convoys. In April and May they made 12 sightings of German submarines, which resulted in three attacks, but the B-24's did not sink a submarine.

Inactivation

To be effective, the U-Boat hunt involved close cooperation among the operational forces of the Army Air Forces and the Navy. Unfortunately, this cooperative attitude did not lessen inter-service rivalries concerning organization, control, and the use of land-based aircraft. The Army Air Forces deemed the Navy's operational control practices involving its aircraft an intolerable situation, using most of AAFAC's specially trained aircraft and crews on endless preventive patrols off the East Coast looking at long stretches of water where submarines no longer ventured.

On 9 July 1943, as a result of a compromise proposal formulated in June by Arnold, Lt. Gen. Joseph T. McNarney, and Rear Adm. John S. McCain, Sr., the Army Air Forces and the U.S. Navy agreed that AAFAC would gradually withdraw from anti-submarine operations. In accordance with this agreement, the AAF by 6 October turned over 77 B-24 Liberators configured with antisubmarine equipment to the U.S. Navy in return for an equal number of unmodified B-24s from the U.S. Navy's allocation. The Navy would then continue to employ both its seaplane and land-based fixed-wing patrol squadrons (VP) and patrol bomber squadrons (VPB) in the antisubmarine warfare mission.

On 31 August the Air Force designated AAFAC as I Bomber Command again and assigned it to the First Air Force. The antisubmarine squadrons were redesignated as heavy bombardment squadrons. The 25th and 26th Antisubmarine Wings were inactivated, but the two antisubmarine groups stationed in England and French Morocco, the 479th Antisubmarine Group at RAF Dunkeswell, England and the 480th Antisubmarine Group at Port Lyautey, French Morocco, continued operations into October 1943 before being disbanded.

Thus, the AAF ended its antisubmarine mission, mostly disdained in spite of its strategic significance as temporary and secondary to the Air Force's responsibilities as a strategic bombing force.

As part of the overall Allied antisubmarine effort, the AAF significantly affected the outcome of the campaign. In terms of the force available, the AAF increased its antisubmarine force from a few obsolete observation aircraft, medium bombers, and B-17s, all without radar, to 187 operational B-24 Liberators, 80 B-25 Mitchells, 12 B-17 Flying Fortresss, and seven Lockheed B-34 Venturas, most equipped with microwave radar and other detection equipment. However the force was dissolved just as it reached a capability second only to escort carrier-based air operations in the ability to defeat submarines, and after the Battle of the Atlantic had peaked.

The AAF's antisubmarine campaign harassed the Germans to the point of ineffectiveness. Even the efforts of the small armed and unarmed Civil Air Patrol aircraft in the shallow coastal waters contributed to this outcome. The German policy from the beginning of the war was to withdraw from areas that became too dangerous because of heavy aerial patrols.

By May 1943, Germany had lost the strategic initiative in the Battle of the Atlantic. Aircraft had forced the enemy to submerge so frequently and stay down for such extended intervals that their targets escaped and U-boat activity became so handicapped that the returns barely justified the expense.

Unit awards

Presidential Unit Citation

480th Antisubmarine Group, 10 November 1942 to 28 October 1943 (Battle of the Atlantic)

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

- Maurer, Maurer (1983). Air Force Combat Units Of World War II. Maxwell AFB, Alabama: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0-89201-092-4.

- Maurer, Maurer, ed. (1982) [1969]. Combat Squadrons of the Air Force, World War II (PDF) (reprint ed.). Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0-405-12194-6. LCCN 70605402. OCLC 72556.

- Army Air Forces Antisubmarine Command History and Photos

- The Battle against the U-boat in the American Theater December 7, 1941 - September 2, 1945

See also

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)