Rotherhithe Tunnel

| |

|---|---|

|

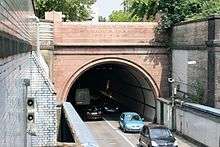

Rotherhithe Tunnel entrance | |

| Route information | |

| History: | Opened in 1904, completed in 1908 |

| Major junctions | |

| North-East end: | Limehouse |

|

| |

| South-West end: | Rotherhithe |

| Road network | |

The Rotherhithe Tunnel is a road tunnel under the River Thames in East London, connecting the Ratcliff district of Limehouse in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets north of the river to Rotherhithe in the London Borough of Southwark south of the river, designated the A101. It was formally opened in 1908 by George Prince of Wales (later King George V), and Richard Robinson, Chairman of the London County Council.

It should not be confused with the nearby earlier and much more historic Thames Tunnel, designed and built under the supervision of Marc Isambard Brunel and his son Isambard Kingdom Brunel, used by London Overground for the East London Line.

Construction

Designed by Sir Maurice Fitzmaurice, the Engineer to the London County Council, construction was authorised by the Thames Tunnel (Rotherhithe and Ratcliff) Act 1900 despite considerable opposition from local residents, nearly 3,000 of whom were displaced by the works.[1]

The work took place between 1904 and 1908, executed by resident engineer Edward H. Tabor and contractors Price and Reeves, at a cost of about £1 million. The tunnel was excavated partly using a tunnelling shield and partly by cut-and-cover. The entrance arches are the cutting edges of the tunnelling shield, which measured 30 feet 8 inches (9.35 m) in diameter,[2] forming in effect a loading gauge for the tunnel.

Physical characteristics

The tunnel consists of a single bore, 4,860 feet (1,481 m) long, carrying a two-lane carriageway 48 feet (14.5 m) below the high-water level of the Thames, with a maximum depth of 75 feet (23 m) below the surface. Four shafts were sunk alongside the tunnel to aid construction, later ventilation and entrance shafts. The two riverside shafts, red brick with stone dressings, had iron spiral staircases as pedestrian entrances. They are closed to the public (the roofs were damaged during World War II, and the iron staircases became dangerous), and the only entrances are the portals (the bases of the staircases can still be seen in the tunnel). Pedestrian and cycle access is permitted, but the distances involved for pedestrians increased significantly when the spiral staircases closed.

The tunnel is entered via a sloping brick-lined cutting at each end leading to the entrance portal, followed by a short cut-and-cover section until the first of the four shafts is reached. The tunneled section is between shafts 1 and 4, measures 3,689 feet (1,125 m) long and is lined with cast iron segments.[3] At the time of its construction, the tunnel was said to be "the largest subaqueous tunnel in existence".[4]

The tunnel was designed to serve foot and horse-drawn traffic between the docks on either side of the river. This accounts for some of its more unusual design features. The roadways are narrow, with each lane only some 8 feet (2.4 m) wide, and footpaths between 4 and 6 feet (1.2 to 2 m) wide on each side. The tunnel is shallow, with a maximum gradient of 1 in 36 (2.8%), to cater for non-mechanised traffic. It includes sharp, nearly right-angled bends at the points where it goes under the river bed. These served two purposes: avoiding the docks on each side of the river, and preventing horses from seeing daylight at the end of the tunnel too early, which might make them bolt for the exit.

This has made it difficult for vehicles to traverse the tunnel safely. Large vehicles cannot easily pass the sharp bends and are therefore banned. The speed limit is 20 miles per hour (32 km/h) and is enforced using average speed cameras. A 2003 survey rated the tunnel the tenth most dangerous tunnel in Europe due to its poor safety features.[5] Its proximity to the river also makes it vulnerable to flooding, as happened in the 1928 Thames flood.[6]

Usage

Like many other London tunnels and bridges, the tunnel carries far more traffic than it was designed for. It was well-used from the start, with 2,600 vehicles a day soon after it opened — a figure which was seen as easily justifying the expense of its construction. By 1955, usage had quadrupled to 10,500 vehicles a day[1] and by 2005 usage had tripled again, to over 34,000 vehicles a day.[7]The heavy usage, particularly during rush hours, can lead to significant congestion and tailbacks.

Alternative crossings include Tower Bridge to the west or the Greenwich foot tunnel to the east. Rotherhithe station is almost adjacent to the southern tunnel entrance, and Limehouse (in Ratcliffe Lane) is the closest station to the northern entrance.

Approximately 20 pedestrians use the tunnel per day.[7] For safety, most cyclists ride along the footpaths on either side of the carriageway.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rotherhithe Tunnel. |

- Crossings of the River Thames

- List of tunnels in the United Kingdom

- Tunnels underneath the River Thames

- Thames Tunnel

References

Notes

- 1 2 "Rotherhithe Tunnel Jubilee", P.L.A. Monthly, Port of London 1955

- ↑ Rolt Hammond, Civil Engineering Plant and Methods, p. 150. (Benn, 1952)

- ↑ Denis Smith, London and the Thames Valley, p. 17. (Thomas Telford, 2000)

- ↑ Henry Jephson, The Making of Modern London: progress & reaction: twenty-one years of the London County council, p. 62. (The London Liberal Federation, 1910)

- ↑ "UK's 'dangerous' road tunnels", BBC News Online, 24 April 2003

- ↑ "The South Side. Damage In Tooleystreet Area." The Times, 9 January 1928

- 1 2 London, Transport for (2005-05-05). "Rotherhithe Tunnel to close on Tuesday nights - Transport for London". tfl.gov.uk. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

External links

Coordinates: 51°30′23″N 0°02′55″W / 51.506501°N 0.048593°W

| |||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||