576i

576i is a standard-definition video mode originally used for broadcast television in most countries of the world where the utility frequency for electric power distribution is 50 Hz. Because of its close association with the colour encoding system, it is often referred to as simply PAL or PAL/SECAM when compared to its 60 Hz (typically, see PAL-M) NTSC-colour-encoded counterpart, 480i. In digital applications it is usually referred to as "576i"; in analogue contexts it is often called "625 lines",[1] and the aspect ratio is usually 4:3 in analogue transmission and 16:9 in digital transmission.

The 576 identifies a vertical resolution of 576 lines, and the i identifies it as an interlaced resolution. The field rate, which is 50 Hz, is sometimes included when identifying the video mode, i.e. 576i50; another notation, endorsed by both the International Telecommunication Union in BT.601 and SMPTE in SMPTE 259M, includes the frame rate, as in 576i/25.

Its basic parameters common to both analogue and digital implementations are: 576 scan lines or vertical pixels of picture content, 25 frames (giving 50 fields) per second.

In analogue 49 additional lines without image content are added to the displayed frame of 576 lines to allow time for older cathode ray tube circuits to retrace for the next frame,[2] giving 625 lines per frame. Digital information not to be displayed as part of the image can be transmitted in the non-displayed lines; teletext and other services and test signals are often implemented.

Analogue television signals have no pixels; they are rastered in scan lines, but along each line the signal is continuous. In digital applications, the number of pixels per line is an arbitrary choice as long as it fulfils the sampling theorem. Values above about 500 pixels per line are enough for conventional broadcast television; DVB-T, DVD and DV allow better values such as 704 or 720.

The video format can be transported by major digital television formats, ATSC, DVB and ISDB, and on DVD, and it supports aspect ratios of standard 4:3 and anamorphic 16:9.

Baseband interoperability (analogue)

When 576i video is transmitted via baseband (i.e., via consumer device cables, not via RF), most of the differences between the "one-letter" systems are no longer significant, other than vertical resolution and frame rate.

In this context, unqualified 576i invariably means

- 625 lines per frame, of which 576 carry picture content

- 25 frames per second interlaced yielding 50 fields per second

- Two interlaced video fields per frame

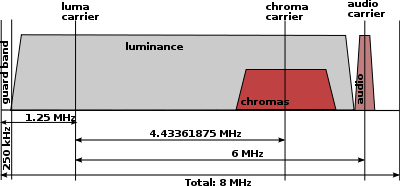

- With PAL or SECAM colour (4.43 MHz or 3.58 MHz (576i-N & 576i-NC))

- frequency-modulated or amplitude-modulated audio (mono)

- Mono or stereo audio, if sent via connector cables between devices

Modulation for TVRO transmission

576i when it is transmitted over free-to-air satellite signals is transmitted substantially differently from terrestrial transmission.

Full transponder mode (e.g., 72 MHz)

- Luma signal is frequency-modulated (FM), but with a 50 Hz dithering signal to spread out energy over the transponder

- Chroma is phase-modulated (PM)

- An FM subcarrier of 4.50, 5.50, 6.0, 6.50 or 6.65 MHz is added for mono sound

- Other FM subcarriers (usually 7.02, 7.20, 7.38, 7.56, 7.74 and 7.92 MHz) are added for a true-stereo service and can also carry multi-lingual sound and radio services. These additional subcarriers are normally narrower bandwidth than the main mono subcarrier and are companded using Panda 1 or similar to preserve the signal-to-noise ratio

- Data subcarriers may also be added

Half-transponder mode (e.g., 36 MHz)

- All of the above is done, but signal is bandwidth-limited to 18 MHz

- The bandwidth limiting does not affect audio subcarriers

Baseband interoperability (digital)

In digital video applications, such as DVDs and digital broadcasting, colour encoding is no longer significant; in that context, 576i means only

- 576 frame lines

- 25 frames or 50 fields per second

- Interlaced video

- PCM audio (baseband)

There is no longer any difference (in the digital domain) between PAL and SECAM. Digital video uses its own separate colour space, so even the minor colour space differences between PAL and SECAM become moot in the digital domain.

Use with progressive sources

When 576i is used to transmit content that was originally composed of 25 full progressive frames per second, the odd field of the frame is transmitted first. This is the opposite of NTSC. Systems which recover progressive frames, or transcode video should ensure that this field order is obeyed, otherwise the recovered frame will consist of a field from one frame and a field from an adjacent frame, resulting in 'comb' interlacing artifacts.

PAL speed-up

Motion pictures are typically shot on film at 24 frames per second. When telecined and played back at PAL's standard of 25 frames per second, films run about 4% faster. This also applies to most TV series that are shot on film or digital 24p.[3] Unlike NTSC's telecine system, which uses 3:2 pulldown to convert the 24 frames per second to the 30 fps frame rate, PAL speed-up results in the telecined video running 4% shorter than the original film as well as the equivalent NTSC telecined video.

Depending on the sound system in use, it also slightly increases the pitch of the soundtrack by 70.67 cents (0.7067 of a semitone). More recently, digital conversion methods have used algorithms which preserve the original pitch of the soundtrack, although the frame rate conversion still results in faster playback.

Conversion methods exist that can convert 24 frames per second video to 25 frames per second with no speed increase, however image quality suffers when conversions of this type are used. This method is most commonly employed through conversions done digitally (i.e. using a computer and software like VirtualDub), and is employed in situations where the importance of preserving the speed of the video outweighs the need for image quality.

Many movie enthusiasts prefer PAL over NTSC despite the former's speed-up, because the latter results in telecine judder, a visual distortion not present in PAL sped-up video.[4] states "the majority of authorities on the subject favour PAL over NTSC for DVD playback quality". Also DVD reviewers often make mention of this cause. For example, in his PAL vs. NTSC article,[5] the founder of MichaelDVD says: "Personally, I find [3:2 pulldown] all but intolerable and find it very hard to watch a movie on an NTSC DVD because of it." In the DVD review of Frequency,[6] one of his reviewers mentions: "because of the 3:2 pull-down artefacts that are associated with the NTSC format (…) I prefer PAL pretty much any day of the week". This is not an issue on modern upconverting DVD players and personal computers, as they play back 23.97 frame/s–encoded video at its true frame rate, without 3:2 pulldown.

Naturally, PAL speed-up does not occur on native 25 fps video, such as British or European TV-series or movies that are shot on video instead of film.

Software which corrects the speed-up is available for those viewing 576i DVD films on their computers, WinDVD's "PAL TruSpeed" being the most ubiquitous. However, this method involves resampling the soundtrack(s), which results in a slight decrease in audio quality.

See also

- List of common resolutions

- 4320p, 2160p, 1080p, 1080i, 720p, 576p, 480p, 480i, 360p, 240p

- Standard-definition television

References

- ↑ afterdawn.com - 576i

- ↑ The 625-line television standard was introduced in the early 1950s. After tracing a frame on a CRT, the electron beam has to be moved from the bottom right to the top left of the screen ready for the next frame. The beam is blanked, no information is transmitted for the duration of 49 lines, and circuitry relatively slow by modern standards executes the retrace.

- ↑ Demtschyna, Michael (2 November 1999). "PAL speedup". www.michaeldvd.com.au. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ↑ http://web.archive.org/web/20060114015926/http://www.dvdlard.co.uk/Content.aspx?ContentID=109 DVDLard] www.dvdlard.co.uk

- ↑ Demtschyna, Michael (7 July 2000). "PAL vs. NTSC". www.michaeldvd.com.au. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ↑ Williams, Paul (28 January 2001). "DVD review Frequency (2000) - R4 vs R1". www.michaeldvd.com.au. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||