31st Fighter Wing

| 31st Fighter Wing | |

|---|---|

| |

| Active | 1947-present |

| Country | United States |

| Branch | United States Air Force |

| Role | Fighter |

| Part of | United States Air Forces Europe |

| Garrison/HQ | Aviano Air Base |

| Motto | Return With Honor |

| Engagements |

|

| Decorations |

Distinguished Unit Citation Presidential Unit Citation Air Force Outstanding Unit Award w/ V Device Republic of Vietnam Gallantry Cross w/ Palm |

| Commanders | |

| Current commander | Brigadier General Barre R. Seguin |

| Notable commanders | Charles F. Wald |

The 31st Fighter Wing (31 FW) is a United States Air Force unit assigned to the United States Air Forces in Europe major command and the Third Air Force. It is stationed at Aviano Air Base, Italy, a North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) base run by the Italian Air Force.

The 31st Fighter Wing is the only United States fighter wing south of the Alps. This strategic location makes the wing important for operations in NATO's southern region.[1] The 31st FW maintains two F-16 fighter squadrons, the 555th Fighter Squadron[2] and the 510th Fighter Squadron,[3] allowing the wing to conduct offense and defensive combat air operations.

In peacetime, the 31st FW prepares for its combat role by maintaining aircraft and personnel in a high state of readiness.[1]

The commander of the 31st Fighter Wing is Brigadier General Barre R. Seguin.[4] The Command Chief Master Sergeant is Chief Master Sergeant Anthony Johnson.[5]

Overview

The 31st Fighter Wing first activated in 1947, but it traces its heritage to its World War II predecessor unit, the 31st Pursuit Group. The group’s lineage began with its activation at Selfridge Field Michigan, on 1 Feb 1940.[6] Redesignated as the 31 Fighter Group shortly before entering the war, it amassed an impressive record. Number one in the Mediterranean theater of operations in terms of aerial victories, the group was involved in 15 WWII campaigns and earned two Distinguished Unit Citations. The wing celebrates the heritage of its predecessor by flying its honors on the wing flag. The group is currently assigned to the wing as the 31st Operations Group.

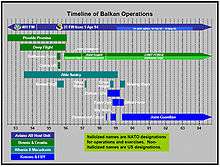

The wing traces its lineage to its activation on 20 November 1947, first designated as the 31st Fighter Wing, and stationed at Turner Airfield, Georgia. Since then, the wing has been stationed at George Air Force Base, California and Homestead Air Force Base, Florida, until finally coming to Aviano Air Base, Italy in April 1994.[6] The 31st Fighter Wing has acted as a key player in several significant engagements and operations during its long history, including several operations in Vietnam, the Balkans and Operation Odyssey Dawn.

Units

The 31st Fighter Wing is made up of four groups, each consisting of several squadrons.

The 31st Operations Group ensures the combat readiness of two F-16CG squadrons, one air control squadron, and one operational support squadron conducting and supporting worldwide air operations. The group prepares fighter pilots, controllers, and support personnel to execute US and North Atlantic Treaty Organization war plans and contingency operations. It trains, equips, plans, and provides weather, intelligence, standardization/evaluation, and command and control sustaining global flying operations.[7]

The 31st Maintenance Group provides peacetime and combat maintenance and munitions control, and executive support for the 31st Fighter Wing, geographically separated units under the command and control of the wing, and units gained during advanced stages of readiness. The group also responds to humanitarian and contingency logistics support requirements as directed by the Joint Chiefs of Staff through Headquarters United States Air Forces Europe (USAFE) to locations in Europe, Africa, and Southwest Asia.[8]

The 31st Mission Support Group’s goal is to provide infrastructure and service to support a premiere combat capability and quality of life to the 31st Fighter Wing, Aviano community and multiple geographically separated units.[9]

The 31st Medical Group supports the readiness of 31st Fighter Wing and associated units throughout the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) southern region, ensuring the health of its community by providing patient-focused medical care from internal, Department of Defense and host nation resources. The unit employs medical resources and preventive initiatives to ensure airmen remain mission ready to support the Expeditionary Air Force, US and NATO objectives worldwide.[10]

Aircraft

The 31st Fighter Wing currently has two operational squadrons, the 555th and 510th Fighter Squadrons flying the F-16G. Both use the tail code "AV" for AViano. Each F-16 has a tail markings in the squadron colors Green with the words "Triple Nickel" in white for the 555th FS and Purple with the words "Buzzards" in white for the 510th FS. The F-16 Fighting Falcon is a compact, multi-role fighter aircraft.[30] It is highly maneuverable and has proven itself in air-to-air combat and air-to-surface attack. It provides a relatively low-cost, high-performance weapon system for the United States and allied nations.[31]

Throughout the wing’s history, the 31st Fighter Wing and its predecessor group have flown several aircraft, including P-35, P-39, P-40 and P-51 aircraft in World War II, F-80 aircraft for a short period from 1946 to 1947, and then P-80s, F-51s and F-84s after World War II. The wing began flying F-100s before the Cuban Missile Crisis and flew that aircraft into the Vietnam War. After the U.S. force reduction in Vietnam, the wing switched to F-4s. In 1970 and 1980, the wing upgraded all F-4Es to F-4Ds and began training all F-4 aircrews. In 1985, the wing received its next aircraft, the F-16 and resumed an air defense mission.[32]

History

World War II

The 31st Pursuit Group, the predecessor unit of the wing's 31st Operations Group, was activated at Selfridge Field, Michigan, on 1 Feb 1940.

In June 1942, the 31st Pursuit Group was transferred to England without planes and began training in British Supermarine Spitfire Mk Vbs at Achem and High Ercall Air Bases. They held the distinction of being the first complete American combat group in the European Theater of Operations and the first to engage in combat.[32] From August through mid-October 1942 the group flew patrols and participated in operations over German controlled France including the Dieppe Raid on 19 Aug.. That day, 2nd Lt. Samuel Junkins became the first American operating in an American combat unit to shoot down a German aircraft operating over the British Isles.[33]

On 14 Oct 1942, the group was declared non-operational on prior to boarding ships bound for its next assignment.

That next assignment included participating in the invasion force that landed in North Africa on 8 Nov 1942, becoming the first American Air Force unit to see combat in theater.[32] They flew from Gibraltar to Tafaraoui Airfield, Algeria, where they scored their first victories in the campaign – shooting down three French fighters that were strafing the airfield just as the 31st arrived. From there they moved quickly from base to base throughout Algeria and Tunisia, engaging in ground attack missions and later escorting P-39s and A-20s on missions to attack German troop positions and convoys. They found themselves as close as 15 miles from the front lines, and this led to near disaster on at least one occasion. During a major German counteroffensive in February 1943, the group was forced to evacuate their position at Thelepte, Tunisia, only a few miles from the advancing German Army, leaving most of their supplies behind. The counteroffensive, however, was short-lived and by May 1943, the Germans surrendered in North Africa. During the North Africa campaign, the group claimed 61 Luftwaffe aircraft destroyed.[32]

One of the highlights of the group’s time in North Africa was the selection of the 308th Fighter Squadron to provide combat air patrols for the arrival of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill at the Casablanca conference in Morocco.[34]

As the Allied Forces looked to Europe, the 31st once again rose to the challenge as they were the first Army Air Forces unit in combat in Malta and Sicily and the first to land in Italy. They distinguished the unit by destroying seven enemy fighters attacking allied shipping during the invasion of Sicily and six more attacking the invasion force on the beaches of Salerno. Their missions consisted mainly of sweeps over allied positions and escorting bombers attacking German positions. January 1944 brought the Allied Landing at Anzio with the 31st the sole provider of air cover for the invasion and beachhead.[32]

In March 1944 the group exchanged their Spitfires for the new North American P-51 Mustangs. This brought about an immediate mission change as the Mustangs enjoyed a much longer range and were tasked to escort heavy bombers on long range missions into Romania, Bulgaria, Austria, France and Northern Italy. During one of their first missions over Ploesti, Romania on 21 April 1944, the group earned their first Distinguished Unit Citation for covering the raids despite severe weather and as many as 50 enemy fighters defending the area. They received their second Distinguished Unit Citation in July 1944 following a mission to escort P-38s on a raid from Ukraine into Romania and Poland. By the time they had returned to Italy, they had destroyed 37 enemy aircraft, including 21 enemy fighter bombers on their way to attack Russian ground forces with no losses of their own.

The 31st remained active through the end of the war, not only flying bomber escort, but also photo reconnaissance and troop carrier escort and took part in Operation Dragoon, the invasion of Southern France. When the shooting stopped, the 31st Fighter Group sat as the undisputed top scoring allied fighter group in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations and the fifth highest overall for the Army Air Forces with 570 confirmed aerial victories. The group sailed to home on 13 August 1945, one of the last units to depart Europe. The unit inactivated on 7 November 1945.[32]

Post World War II

Following the war, the 31st Fighter Group, as it was now called, activated at Giebelstadt Army Airfield, Germany as part of the US occupation forces, on 20 August 1946, where they flew Lockheed P-80 Shooting Stars, the first operational American jet fighter aircraft. From there the unit transferred without personnel of equipment to Langley Field, Virginia in June 1947 and then to Turner Field, Georgia, in September of that same year.

Two months later in November, the 31st Fighter Wing was organized as part of the test by the Air Force of the wing base organization system, which unified combat groups and their support organizations under a single wing, carrying the same number as the combat group. The 31st Fighter Group became the combat component of the new wing. The experiment proved successful and the Air Force adopted it on a permanent basis in the summer of 1948, making the wing its basic combat unit.[35] Originally assigned F-51 Mustangs, the wing began converting to Republic F-84 Thunderjets in August 1948. In 1950 the wing transferred from Tactical Air Command to Strategic Air Command and was redesignated as the 31st Fighter-Escort Wing.[6]

In August 1951 the 31st Wing became the first unit to receive the upgraded F-84G model of the Thunderjet. In addition to engine, armament and avionics updates, the F-84G was the first fighter designed for air refueling and the first single seat fighter-bomber with a designed nuclear delivery capability.[36]

Operation Fox Peter One

The wing pioneered the development of in flight refueling tactics. On 6 July 1952 the wing executed Operation Fox Peter One, the mass movement of the entire wing from Turner Field to Misawa Air Base, Japan using aerial refueling to fly non-stop from Turner to Travis Air Force Base, California, and from Travis to Hickam Air Force Base, Hawaii. The unit then island-hopped across the rest of the Pacific with stops at Midway and Wake Islands, Eniwetok Atoll, Guam, Iwo Jima and Yokota Air Base, Japan.[37]

The sheer magnitude of this accomplishment was sufficient to name the 31st Fighter Escort Wing as the recipient of the first-ever Air Force Outstanding Unit Award. The wing commander, Colonel David C. Schilling, won the Air Force Association Trophy, which was later named after him. This movement included the longest over-water flight attempted to that date and was the first trans-Pacific mass flight of jet aircraft. As an encore, on 20 August 1953, Col Schilling led a flight of eight F-84s on a 10.5-hour non-stop flight from Turner Field to Nouasseur Air Base, French Morocco. This successful flight culminated in the 40th Air Division of the Strategic Air Command receiving the Mackay Trophy[38] in 1953.

During 1953, the wing, then known as the 31st Strategic Fighter Wing, deployed to Japan and Alaska to provide air defense in the northern Pacific.

On 15 March 1959, the wing moved without people or equipment to George Air Force Base, California During the wing’s time in California, it deployed units for four-month alert rotations to Moron Air Base, Spain and Aviano Air Base, Italy.[32]

Cuban Missile Crisis and Vietnam War

During the Berlin Crisis in October and November 1961, the wing deployed its 309th Fighter Squadron to Spangdahlem Air Base, Germany to bolster the U.S. military forces in Europe. During 1962, the wing moved from George to Homestead Air Force Base, Florida, while simultaneously deploying a squadron to Kadena Air Base, Japan for four months without losing any operational capability. Then, during the Cuban missile crisis in October 1962, the 31st planned operational missions and participated in events that ultimately led to the removal of missiles from Cuba. In recognition of these achievements, the wing was awarded its second Outstanding Unit Award.[32]

On 8 February 1964, the 308th Fighter Squadron flew a non-stop mission from Homestead to Cigli Air Base, Turkey. The 6,600-mile trip required eight in-flight refuelings and set a new record for the longest mass flight of jet aircraft to cross the Atlantic. The flight also led to the wing receiving the Tactical Air Command Outstanding Fighter Wing Award for 1964 for the second consecutive year.[32]

In June 1965, the wing deployed the 307th Tactical Fighter Squadron to Bien Hoa Air Base, Republic of Vietnam. The wing sent the 308th Tactical Fighter Squadron to replace them in December on a permanent change of station. The following April, the 307th squadron moved to Torrejon Air Base, Spain and in November 1966, the wing received orders to deploy to Tuy Hoa Air Base, Republic of Vietnam.

The 31st wing arrived at Tuy Hoa, and was assigned to the 7th Air Force, on Christmas Day 1966. The wing provided close air support and air interdiction for US and Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) units in the central region of the country. In 1968 they helped defend installations against enemy forces during the Tet Offensive and the siege of Khe Sanh and were later singled out for their outstanding contribution during the extraction of friendly forces from Kham Duc. They reached the 100,000 combat sortie milestone in September 1969. The wing earned two Outstanding Unit Awards, one with a combat “V” device, a Presidential Unit Citation, two Republic of Vietnam Gallantry Crosses with Palm and ten campaign streamers for action in Vietnam. On 15 October 1970, the wing returned to Homestead without people or equipment as part of the United States force reduction in Vietnam. At the same time, the wing switched from flying North American F-100 Super Sabres to McDonnell Douglas F-4E Phantom IIs.[39]

1971–1990

The wing assumed a dual-role function with the primary mission of air defense of southern Florida and the secondary as a replacement training unit. Two of the wing's fighter squadrons, the 307th and 309th, were designated to perform pilot replacement training. From April to August 1972, the 308th deployed to Udorn Royal Thai Air Force Base, Thailand to augment tactical air forces already deployed to that country, followed in July by the 307th TFS. In June 1972, Captains John Cerak and David B. Dingee of the 308th Tactical Fighter Squadron were shot down and captured by North Vietnamese forces and were confirmed as prisoners of war. They were both released and returned to the United States in March 1973.[40][41] On 27 June 1972, Lt Col Farrell J. Sullivan and Captain Richard L. Francis of the 523d Tactical Fighter Squadron of the 405th Fighter Wing were shot down over Hanoi while flying an F-4E assigned to the 308th squadron while the 308th was on temporary duty at Udorn. Lt. Col Sullivan was classified as missing in action and following the war, was reclassified as killed in action. Captain Francis was captured and remained a POW until his release at the end of hostilities on 28 March 1973.

On 15 October 1972, Captains James L. Hendrickson and Gary M. Rubus[42] of the 307th Tactical Fighter Squadron[43] shot down a MiG-21 northeast of Hanoi. This marked the first aerial victory for the wing in Vietnam and the first for the wing since the end of World War II.

In 1979 and 1980, the wing transferred its F-4Es to Air National Guard units and the Egyptian Air Force, and began operating F-4Ds.[32]

On 30 March 1981, the wing assumed a larger responsibility for training all F-4 aircrews. Training became the wing's primary mission until 1985 when the wing received its next aircraft, the General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon, and resumed an air defense mission. The 31st Tactical Fighter Training Wing won the 1982 Daedalian Maintenance Trophy Award for the best maintenance complex in the United States Air Force.

Hurricane Andrew and Balkan Operations

As part of the most extensive restructuring since the Air Force became a separate service, Tactical Air Command was inactivated and Air Combat Command was activated and the 31st Tactical Fighter Wing was redesignated to its current name, the 31st Fighter Wing.[6]

On 24 August 1992 Hurricane Andrew swept across southern Florida, leaving extensive damage in its wake. Every building at Homestead AFB received some damage, many buildings were destroyed.[44] The fighter squadrons evacuated most of the planes before the storm but were unable to return. In the aftermath, the Secretary of Defense recommended complete closure of the base, but in June 1993, the Base Realignment and Closure Commission recommended realigning the base under the Air Force Reserve Command and inactivating the 31st Fighter Wing. The squadrons were assigned to other wings and the 31st began inactivation proceedings.

To avoid losing the wing’s heritage and history as the highest scoring Army Air Force unit in the Mediterranean Theater in WWII, the impressive combat record in Vietnam and number of significant firsts they produced in the early years of the Air Force, the 31st was chosen to move rather than fade into obscurity. On 1 April 1994, the 31st Fighter Wing inactivated at Homestead and subsequently activated at Aviano Air Base, Italy in place of the 401st Fighter Wing.[32]

The 31st received two new squadrons at that time, the 555th and 510th Fighter Squadrons, along with their Block-40 F-16s. The wing immediately become involved with events in Bosnia, part of the former communist country of Yugoslavia, in May 1994 as part of Operation Deny Flight. A year later, a massive search and rescue operation took place to extract Captain Scott O’Grady[45] of the 555th FS from behind enemy lines. An HH-53 of the United States Marine Corps picked him up after he evaded capture for six days.[45]

In August and September, Operation Deliberate Force began and the 31st conducted air strikes against Bosnian Serbs conducting ethnic purges among the Muslim population of the country. Peacekeeping operations continued in the Balkans through the end of 2004, when the European Union assumed responsibility for the region.[46]

In 1999, USAFE activated the 31st Air Expeditionary Wing-NOBLE ANVIL (31st AEW) at Aviano for Operation Allied Force, the NATO operation to stop Serbian atrocities in the Province of Kosovo. Assigned under a joint task force, the 31st AEW, flew from Aviano and joined NATO allies in a 78-day air campaign against Serbia. From 24 March to 10 June 1999, the 31st AEW, the largest expeditionary wing in Air Force history flew nearly 9,000 combat sorties and accumulated almost 40,000 hours of combat service over the skies of Kosovo, Serbia and the rest of the Balkans in support of NATO operations. The wing accomplished much during Opearation Allied Force as the two permanently assigned flying squadrons, the 510th and 555th, flew more than 2,400 combined sorties and more than 10,000 combat hours.[47]

Operations in Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya

In 2000, the wing began deployments in support of the Expeditionary Air Force. From March to September 2000, the 510th and 555th Fighter Squadrons conducted back-to-back deployments to Ahmed Al Jaber Air Base, Kuwait, in support of Operation Southern Watch. While at Al Jaber, the squadrons flew more than 400 combat sorties. From June through December 2001, the fighter squadrons deployed combat search and rescue capabilities three times and helped enforce the no fly zone over Iraq.

From August to December 2002, the 510th Fighter Squadron and 603d Air Control Squadron returned to Southwest Asia. The two squadrons supported Operation Enduring Freedom. Simultaneously, the 555th deployed personnel and aircraft to Decimomannu Air Base, Sardinia while the runway at Aviano closed for repairs.

The wing’s support of Operation Iraqi Freedom began in late 2003. Aviano served as the launch point for insertion of airborne forces opening a second front in northern Iraq. During that time, the wing secured, bedded and fed more than 2,300 Army and Air Force personnel. The operation, the largest airborne operation since 1989, constituted 62 missions, transporting 2,146 passengers and 2,433.7 tons of cargo.

Since the beginning of combat operations in Iraq, forces from the wing have been on regular combat rotations into the region. In late 2003, the wing’s 603rd Air Control Squadron became the first unit from the wing to deploy to Iraq. They also relocated their entire operation from Baghdad International Airport to Balad Air Base. Under combat conditions, the squadron transferred $73 million in equipment and more than 100 personnel with 20 convoys. On 10 April 2004, insurgents launched a mortar attack on Balad, killing Airman First Class Antoine Holt[48] and injuring two other 603rd members. Airman Holt’s death constituted the 31st wing’s first combat fatality since the Vietnam War.

The 31st Fighter Wing continued deploying forces in support of Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Force, with more than one-third of the wing deploying to support operations each year from 2003 to 2007.

In 2007, the 555th FS deployed to Kunsan Air Base, Republic of Korea. Since arriving at Aviano, the wing has also participated in numerous training exercises with international partners, including training deployments to Latvia, the Czech Republic, Romania, Bulgaria, Spain, Slovenia and Poland.

In March 2011, the 31st played a major role in the United Nations' response to the crisis in Libya, known as Operation Odyssey Dawn, in enforcing a no-fly zone over Libya.[49] The wing hosted four flying units and more than 1,350 personnel during the 15-day operation, 17–31 March. It worked around the clock to launch 2,250 flying operations out of Aviano. As the operation came to an end on 31 March, so began Operation Unified Protector, with NATO taking the lead until the operation's conclusion 31 Oct of that year.[32]

In July 2015, the United States and Turkey reached agreement on Turkish support for actions against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant. As a result of this agreement, the United States Central Command announded in August that six Fighting Falcons of the 31st had deployed to Incirlik Air Base to begin operations against the Islamic State.[50]

Lineage

- Designated as the 31st Fighter Wing on 6 November 1947

- Organized on 20 November 1947

- Discontinued on 25 August 1948

- Activated on 23 August 1948[note 1]

- Redesignated 31st Fighter-Bomber Wing on 20 January 1950

- Redesignated 31st Fighter-Escort Wing on 16 July 1950

- Redesignated 31st Strategic Fighter Wing on 20 January 1953

- Redesignated 31st Fighter-Bomber Wing on 1 April 1957

- Redesignated 31st Tactical Fighter Wing on 1 July 1958

- Redesignated 31st Tactical Training Wing on 30 March 1981

- Redesignated 31st Tactical Fighter Wing on 1 October 1985

- Redesignated 31st Fighter Wing on 1 October 1991.[6]

Assignments

|

|

Stations

- Turner Field (later Turner Air Force Base), Georgia, 20 November 1947

- George Air Force Base, California, 15 March 1959

- Homestead Air Force Base, Florida, 31 May 1962 – 6 December 1966

- Tuy Hoa Air Base, Republic of Vietnam, 16 December 1966 – 15 October 1970

- Homestead Air Force Base, Florida, 15 October 1970 – 1 April 1994

- Aviano Air Base, Italy, 1 April 1994–present[6]

Unit emblems

| Gallery |

|---|

|

See also

References

- ↑ The 1948 discontinuance and activation reflect a replacement of a Table of Distribution headquarters by a Table of Organization headquarters for the wing and do not change the wing lineage

Citations

- 1 2 3 "31st Fighter Wing Fact Sheet". 31st Fighter Wing Public Affairs Office. 23 September 2013. Archived from the original on 31 October 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- 1 2 "555th Fighter Squadron "Triple Nickel" Factsheet". 31st Fighter Wing Public Affairs Office. 15 April 2009. Archived from the original on 17 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- 1 2 "510th Fighter Squadron "Buzzards" Factsheet". 31st Fighter Wing Public Affairs Office. 28 April 2009. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ USAF Biography, Brigadier General Barre R. Seguin May 2013 Archived 30 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Aviano Air Base Biography Chief Master Sergeant Anthony Johnson June 2013 Archived 30 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Robertson, Patsy (22 September 2008). "Factsheet 31 Fighter Wing (USAFE)". Air Force Historical Research Agency. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- 1 2 "31st Operations Group Fact Sheet". 31st Fighter Wing Public Affairs Office. 24 April 2009. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- 1 2 "31st Maintenance Group Factsheet". 31st Fighter Wing Public Affairs Office. 28 April 2009. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- 1 2 "31st Mission Support Group Factsheet". 31st Fighter Wing Public Affairs Office. 28 April 2009. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- 1 2 "31st Medical Group Factsheet". 31st Fighter Wing Public Affairs Office. 24 April 2009. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "31st Comptroller Squadron Factsheet". 31st Fighter Wing Public Affairs Office. 1 January 2010. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "603d Air Control Squadron Factsheet". 31st Fighter Wing Public Affairs Office. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "31st Operations Support Squadron Factsheet". 31st Fighter Wing Public Affairs Office. 24 April 2009. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "31st Maintenance Squadron Factsheet". 31st Fighter Wing Public Affairs Office. December 7, 2009. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "31st Aircraft Maintenance Squadron Factsheet". 31st Fighter Wing Public Affairs Office. 20 April 2009. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "31st Maintenance Operations Squadron Factsheet". 31st Fighter Wing Public Affairs Office. 29 April 2009. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "31st Munitions Maintenance Squadron Factsheet". 31st Fighter Wing Public Affairs Office. February 10, 2010. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "731st Munitions Maintenance Squadron Factsheet". 31st Fighter Wing Public Affairs Office. 19 March 2010. Archived from the original on 27 February 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "31st Contracting Squadron Factsheet". 31st Fighter Wing Public Affairs Office. April 21, 2009. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "31st Security Forces Squadron Factsheet". 31st Fighter Wing Public Affairs Office. 21 April 2009. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "31st Force Support Squadron Factsheet". 31st Fighter Wing Public Affairs Office. 20 April 2009. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "31st Logistics Readiness Squadron Factsheet". 31st Fighter Wing Public Affairs Office. 24 August 2009. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "31st Communications Squadron Factsheet". 31st Fighter Wing Public Affairs Office. 21 April 2009. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "31st Civil Engineer Squadron Factsheet". 31st Fighter Wing Public Affairs Office. 20 April 2009. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "31st Aerospace Medicine Squadron Factsheet". 31st Fighter Wing Public Affairs Office. 22 March 2010. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "31st Dental Squadron Factsheet". 31st Fighter Wing Public Affairs Office. 16 December 2009. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "31st Medical Operations Squadron Factsheet". 31st Fighter Wing Public Affairs Office. 24 April 2009. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "31st Surgical Operations Squadron Factsheet". 31st Fighter Wing Public Affairs Office. 24 April 2009. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "31st Medical Support Squadron Factsheet". 31st Fighter Wing Public Affairs Office. 24 April 2009. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "F-16 Fighting Falcon Factsheet". Air Combat Command Public Affairs Office. 21 May 2012. Archived from the original on 1 August 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "F-16 Fighting Falcon". Lockheed Martin. Archived from the original on 10 April 2014. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Bourgeois, Lane M, (12 June 2012). "A History of the 31st Fighter Wing" (PDF). 31st Fighter Wing History Office. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 February 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "Air Force History Milestones". Air Force Historical Research Agency. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "This Week in 31st Fighter Wing History: 308th Fighter Squadron deploys to Morocco". www.aviano.af.mil. 18 January 2011. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ Ravenstein, p. xxi

- ↑ Knaack, p. 36

- ↑ Bourgeois, Lane. "31st FW celebrates historic operation". Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ Mackay Trophy

- ↑ "This Week in 31st Fighter Wing History: F-100s serve in Vietnam". www.aviano.af.mil. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "Military Times Hall of Valor John P. Cerak". Military Times. 22 September 2008. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "Veteran Tributes: David B. Dingee". Veteran Tributes.org. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "Biography, Colonel Gary M. Rubus". October 1998. Archived from the original on 31 March 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ the 307th replaced the 308th at Udorn

- ↑ Allen, Greg (23 August 2012). "Hurricane Andrew's Legacy: 'Like A Bomb' In Florida". www.npr.org. Archived from the original on 19 March 2014. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- 1 2 Fedarko, Kevin (19 June 1995). "RESCUING SCOTT O'GRADY: ALL FOR ONE". Time Magazine. Archived from the original on 12 August 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "Operation Deliberate Force: Ten years on". NATO. Archived from the original on 10 September 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "Factsheet Operation Allied Force". Air Force Historical Studies Office. 23 August 2012. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "Honor the Fallen" Airman 1st Class Antoine Holt". Military Times. 22 September 2008. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ UNSR 1973 United Nations Security Council Recolution 1973 (2011) Archived 1 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Pellerin, Cheryl (August 17, 2015). "US, Turkey finalizing details of anti-ISIL airstrikes". DoD News. Retrieved September 7, 2015.

Bibliography

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

- Knaack, Marcelle Size (1978). Encyclopedia of US Air Force Aircraft and Missile Systems (PDF). Vol. 1, Post-World War II Fighters 1945-1973. Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 978-0-912799-19-3.

- Ravenstein, Charles A. (1984). Air Force Combat Wings, Lineage & Honors Histories 1947-1977 (PDF). Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0-912799-12-9.

- Further reading

- Endicott, Judy G. Active Air Force Wings as of 1 October 1995; USAF Active Flying, Space, and Missile Squadrons as of 1 October 1995. Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama: Office of Air Force History, 1999. CD-ROM.

- Fletcher, Harry R (1993). Air Force Bases , Vol. II, Air Bases Outside the United States of America (PDF). Washington, DC: Center for Air Force History. ISBN 0-912799-53-6.

- Martin, Patrick (1994). Tail Code The Complete History of USAF Tactical Aircraft Tail Code Markings. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-0-88740-513-6.

- Mueller, Robert (1989). Air Force Bases, Vol. I, Active Air Force Bases Within the United States of America on 17 September 1982 (PDF). Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0-912799-53-6.

- Rogers, Brian (2005). United States Air Force Unit Designations Since 1978. Ian Allen Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85780-197-2.

External links

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||