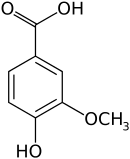

Vanillic acid

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

4-Hydroxy-3-methoxybenzoic acid | |||

| Other names

4-Hydroxy-m-anisic acid, Vanillate | |||

| Identifiers | |||

| 121-34-6 | |||

| ChEBI | CHEBI:30816 | ||

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL120568 | ||

| ChemSpider | 8155 | ||

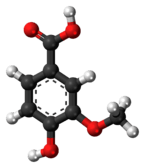

| Jmol interactive 3D | Image | ||

| PubChem | 8468 | ||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C8H8O4 | |||

| Molar mass | 168.14 g/mol | ||

| Appearance | White to light yellow powder or crystals | ||

| Melting point | 210 to 213 °C (410 to 415 °F; 483 to 486 K) | ||

| Hazards | |||

| NFPA 704 | |||

| Related compounds | |||

| Related compounds |

Vanillin, vanillyl alcohol | ||

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| | |||

| Infobox references | |||

Vanillic acid (4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzoic acid) is a dihydroxybenzoic acid derivative used as a flavoring agent. It is an oxidized form of vanillin. It is also an intermediate in the production of vanillin from ferulic acid.[2][3]

Occurrence in nature

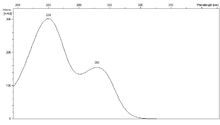

Vanillic acid UV visible spectrum

The highest amount of vanillic acid in plants known so far is found in the root of Angelica sinensis,[4] a herb indigenous to China, which is used in traditional Chinese medicine.

Occurrences in food

Açaí oil, obtained from the fruit of the açaí palm (Euterpe oleracea), is rich in vanillic acid (1,616 ± 94 mg/kg).[5]

It is one of the main natural phenols in argan oil.[6]

It is also found in wine and vinegar.[7]

Metabolism

Vanillic acid is one of the main catechins metabolites found in humans after consumption of green tea infusions.[8]

References

- ↑ "Vanillic acid (4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzoic acid)". chemicalland21.com. Retrieved 2009-01-28.

- ↑ Lesage-Meessen L, Delattre M, Haon M, Thibault JF, Ceccaldi BC, Brunerie P, Asther M (October 1996). "A two-step bioconversion process for vanillin production from ferulic acid combining Aspergillus niger and Pycnoporus cinnabarinus". J. Biotechnol. 50 (2–3): 107–113. doi:10.1016/0168-1656(96)01552-0. PMID 8987621.

- ↑ Civolani C, Barghini P, Roncetti AR, Ruzzi M, Schiesser A (June 2000). "Bioconversion of ferulic acid into vanillic acid by means of a vanillate-negative mutant of Pseudomonas fluorescens strain BF13". Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66 (6): 2311–2317. doi:10.1128/AEM.66.6.2311-2317.2000. PMC 110519. PMID 10831404.

- ↑ Duke, JA (1992). Handbook of phytochemical constituents of GRAS herbs and other economic plants. CRC Press, 999 edition. ISBN 978-0-8493-3865-6.

- ↑ Pacheco-Palencia LA, Mertens-Talcott S, Talcott ST (Jun 2008). "Chemical composition, antioxidant properties, and thermal stability of a phytochemical enriched oil from Acai (Euterpe oleracea Mart.)". J Agric Food Chem 56 (12): 4631–4636. doi:10.1021/jf800161u. PMID 18522407.

- ↑ Phenols and Polyphenols from Argania spinosa. Z. Charrouf and D. Guillaume, American Journal of Food Technology, 2007, 2, pp. 679–683, doi:10.3923/ajft.2007.679.683

- ↑ Analysis of polyphenolic compounds of different vinegar samples. Miguel Carrero Gálvez, Carmelo García Barroso and Juan Antonio Pérez-Bustamante, Zeitschrift für Lebensmitteluntersuhung und -Forschung A, Volume 199, Number 1, pp. 29–31, doi:10.1007/BF01192948

- ↑ Catechin metabolites after intake of green tea infusions. P. G. Pietta, P. Simonetti, C. Gardana, A. Brusamolino, P. Morazzoni and E. Bombardelli, BioFactors, 1998, Volume 8, Issue 1–2, pp. 111–118,doi:10.1002/biof.5520080119

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This article is issued from Wikipedia - version of the Monday, November 02, 2015. The text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share Alike but additional terms may apply for the media files.