Conjunctive normal form

In Boolean logic, a formula is in conjunctive normal form (CNF) or clausal normal form if it is a conjunction of clauses, where a clause is a disjunction of literals; otherwise put, it is an AND of ORs. As a normal form, it is useful in automated theorem proving. It is similar to the product of sums form used in circuit theory.

All conjunctions of literals and all disjunctions of literals are in CNF, as they can be seen as conjunctions of one-literal clauses and conjunctions of a single clause, respectively. As in the disjunctive normal form (DNF), the only propositional connectives a formula in CNF can contain are and, or, and not. The not operator can only be used as part of a literal, which means that it can only precede a propositional variable or a predicate symbol.

In automated theorem proving, the notion "clausal normal form" is often used in a narrower sense, meaning a particular representation of a CNF formula as a set of sets of literals.

Examples and non-examples

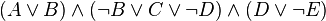

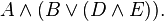

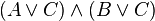

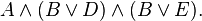

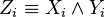

All of the following formulas in the variables A, B, C, D, and E are in conjunctive normal form:

The last formula is in conjunctive normal form because it can be seen as the conjunction of the two single-literal clauses  and

and  .

Incidentally, the last two formulas are also in disjunctive normal form.

.

Incidentally, the last two formulas are also in disjunctive normal form.

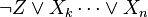

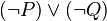

The following formulas are not in conjunctive normal form:

Every formula can be equivalently written as a formula in conjunctive normal form. In particular this is the case for the three non-examples just mentioned; they are respectively equivalent to the following three formulas, which are in conjunctive normal form:

Conversion into CNF

Every propositional formula can be converted into an equivalent formula that is in CNF. This transformation is based on rules about logical equivalences: the double negative law, De Morgan's laws, and the distributive law.

Since all logical formulae can be converted into an equivalent formula in conjunctive normal form, proofs are often based on the assumption that all formulae are CNF. However, in some cases this conversion to CNF can lead to an exponential explosion of the formula. For example, translating the following non-CNF formula into CNF produces a formula with  clauses:

clauses:

In particular, the generated formula is:

This formula contains  clauses; each clause contains either

clauses; each clause contains either  or

or  for each

for each  .

.

There exist transformations into CNF that avoid an exponential increase in size by preserving satisfiability rather than equivalence.[1][2] These transformations are guaranteed to only linearly increase the size of the formula, but introduce new variables. For example, the above formula can be transformed into CNF by adding variables  as follows:

as follows:

An interpretation satisfies this formula only if at least one of the new variables is true. If this variable is  , then both

, then both  and

and  are true as well. This means that every model that satisfies this formula also satisfies the original one. On the other hand, only some of the models of the original formula satisfy this one: since the

are true as well. This means that every model that satisfies this formula also satisfies the original one. On the other hand, only some of the models of the original formula satisfy this one: since the  are not mentioned in the original formula, their values are irrelevant to satisfaction of it, which is not the case in the last formula. This means that the original formula and the result of the translation are equisatisfiable but not equivalent.

are not mentioned in the original formula, their values are irrelevant to satisfaction of it, which is not the case in the last formula. This means that the original formula and the result of the translation are equisatisfiable but not equivalent.

An alternative translation, the Tseitin transformation, includes also the clauses  . With these clauses, the formula implies

. With these clauses, the formula implies  ; this formula is often regarded to "define"

; this formula is often regarded to "define"  to be a name for

to be a name for  .

.

First-order logic

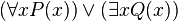

In first order logic, conjunctive normal form can be taken further to yield the clausal normal form of a logical formula, which can be then used to perform first-order resolution. In resolution-based automated theorem-proving, a CNF formula

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

, with  literals, is commonly represented as a set of sets literals, is commonly represented as a set of sets | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

. |

See below for an example.

Computational complexity

An important set of problems in computational complexity involves finding assignments to the variables of a boolean formula expressed in Conjunctive Normal Form, such that the formula is true. The k-SAT problem is the problem of finding a satisfying assignment to a boolean formula expressed in CNF in which each disjunction contains at most k variables. 3-SAT is NP-complete (like any other k-SAT problem with k>2) while 2-SAT is known to have solutions in polynomial time. As a consequence,[3] the task of converting a formula into a DNF, preserving satisfiability, is NP-hard; dually, converting into CNF, preserving validity, is also NP-hard; hence equivalence-preserving conversion into DNF or CNF is again NP-hard.

Typical problems in this case involve formulas in "3CNF": conjunctive normal form with no more than three variables per conjunct. Examples of such formulas encountered in practice can be very large, for example with 100,000 variables and 1,000,000 conjuncts.

A formula in CNF can be converted into an equisatisfiable formula in "kCNF" (for k>=3) by replacing each conjunct with more than k variables  by two conjuncts

by two conjuncts  and

and  with

with  a new variable, and repeating as often as necessary.

a new variable, and repeating as often as necessary.

Converting from first-order logic

To convert first-order logic to CNF:[4]

- Convert to negation normal form.

- Eliminate implications and equivalences: repeatedly replace

with

with  ; replace

; replace  with

with  . Eventually, this will eliminate all occurrences of

. Eventually, this will eliminate all occurrences of  and

and  .

. - Move NOTs inwards by repeatedly applying De Morgan's Law. Specifically, replace

with

with  ; replace

; replace  with

with  ; and replace

; and replace  with

with  ; replace

; replace  with

with  ;

;  with

with  . After that, a

. After that, a  may occur only immediately before a predicate symbol.

may occur only immediately before a predicate symbol.

- Eliminate implications and equivalences: repeatedly replace

- Standardize variables

- For sentences like

which use the same variable name twice, change the name of one of the variables. This avoids confusion later when dropping quantifiers later. For example,

which use the same variable name twice, change the name of one of the variables. This avoids confusion later when dropping quantifiers later. For example, ![\forall x [\exists y Animal(y) \land \lnot Loves(x, y)] \lor [\exists y Loves(y, x)]](../I/m/27f3ca063d06ce22104d44e1eb779738.png) is renamed to

is renamed to ![\forall x [\exists y Animal(y) \land \lnot Loves(x, y)] \lor [\exists z Loves(z,x)]](../I/m/1f642db8f8ee5e29d5330fdd91914cd8.png) .

.

- For sentences like

- Skolemize the statement

- Move quantifiers outwards: repeatedly replace

with

with  ; replace

; replace  with

with  ; replace

; replace  with

with  ; replace

; replace  with

with  . These replacements preserve equivalence, since the previous variable standardization step ensured that

. These replacements preserve equivalence, since the previous variable standardization step ensured that  doesn't occur in

doesn't occur in  . After these replacements, a quantifier may occur only in the initial prefix of the formula, but never inside a

. After these replacements, a quantifier may occur only in the initial prefix of the formula, but never inside a  ,

,  , or

, or  .

. - Repeatedly replace

with

with  , where

, where  is a new

is a new  -ary function symbol, a so-called "skolem function". This is the only step that preserves only satisfiability rather than equivalence. It eliminates all existential quantifiers.

-ary function symbol, a so-called "skolem function". This is the only step that preserves only satisfiability rather than equivalence. It eliminates all existential quantifiers.

- Move quantifiers outwards: repeatedly replace

- Drop all universal quantifiers.

- Distribute ORs inwards over ANDs: repeatedly replace

with

with  .

.

As an example, the formula saying "Who loves all animals, is in turn loved by someone" is converted into CNF (and subsequently into clause form in the last line) as follows (highlighting replacement rule redices in  ):

):

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

by 1.1 | ||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

by 1.1 | |||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

by 1.2 | |||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

by 1.2 | ||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

by 1.2 | ||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

by 2 | ||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

by 3.1 | |||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

by 3.1 | |||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

by 3.2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

by 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

by 5 | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(clause representation) |

Informally, the skolem function  can be thought of as yielding the person by whom

can be thought of as yielding the person by whom  is loved, while

is loved, while  yields the animal (if any) that

yields the animal (if any) that  doesn't love. The 3rd last line from below then reads as "

doesn't love. The 3rd last line from below then reads as " doesn't love the animal

doesn't love the animal  , or else

, or else  is loved by

is loved by  ".

".

The 2nd last line from above,  , is the CNF.

, is the CNF.

Notes

- ↑ Tseitin (1968)

- ↑ Jackson and Sheridan (2004)

- ↑ since one way to check a CNF for satisfiability is to convert it into a DNF, the satisfiability of which can be checked in linear time

- ↑ Artificial Intelligence: A modern Approach [1995...] Russell and Norvig

See also

References

- Paul Jackson, Daniel Sheridan: Clause Form Conversions for Boolean Circuits. In: Holger H. Hoos, David G. Mitchell (Eds.): Theory and Applications of Satisfiability Testing, 7th International Conference, SAT 2004, Vancouver, BC, Canada, May 10–13, 2004, Revised Selected Papers. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 3542, Springer 2005, pp. 183–198

- G.S. Tseitin: On the complexity of derivation in propositional calculus. In: Slisenko, A.O. (ed.) Structures in Constructive Mathematics and Mathematical Logic, Part II, Seminars in Mathematics (translated from Russian), pp. 115–125. Steklov Mathematical Institute (1968)

External links

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Conjunctive normal form", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- Java applet for converting to CNF and DNF, showing laws used

- Mayuresh S. Pardeshi, Dr. Bashirahamed F. Momin "Conversion of cnf to dnf using grid computing" IEEE, ISBN 978-1-4673-2816-6

- Mayuresh S. Pardeshi, Dr. Bashirahamed F. Momin "Conversion of cnf to dnf using grid computing in parallel" IEEE, ISBN 978-1-4799-4041-7