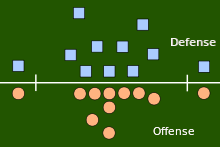

3–4 defense

In American football, the 3–4 defense is a defensive alignment consisting of three down linemen and four linebackers.

| “ | In general, ideal front-seven players in the 3–4 are bigger and need to take on and defeat blocks more often in the running game. | ” |

The 3–4 defense incorporates three defensive linemen - two defensive ends and one nose tackle, who line up opposite the other team's offensive line. Those three players are responsible for engaging the other team's offensive line, allowing the four linebackers to either rush the quarterback or drop back into coverage, depending on the situation. While the role of the defensive linemen is fairly consistent, the linebackers allow for the flexibility and versatility of the 3-4 scheme, and give defensive coaches nearly limitless options to confuse the other team's players and coaches. Depending on the situation, any number of linebackers can blitz, fake a blitz, "spy" the quarterback or running back, or cover receivers. In key situations, a rush linebacker may be sent to cover the flat on the opposite side of the blitzing defensive back; this is called a "zone blitz".

After becoming the predominant defensive alignment in the late 1970s-early 1980s,[2] the 3–4 defense declined in popularity over the next two decades, but experienced a resurgence in the 2000s among both professional and college football teams. As of 2015, NFL teams that regularly incorporate the 3–4 defensive alignment scheme as a base include the Cleveland Browns, Buffalo Bills, San Diego Chargers, Green Bay Packers, Baltimore Ravens, Arizona Cardinals, Indianapolis Colts, Kansas City Chiefs, New York Jets, San Francisco 49ers, Pittsburgh Steelers, Washington Redskins, Denver Broncos, Tennessee Titans, Houston Texans, and the Chicago Bears, who will be the last team to use the defense on a regular basis. The New England Patriots returned to a 4–3 defensive front at the end of the 2011 season..

The Pittsburgh Steelers have used the 3–4 as their base defense since 1982, the season after Hall of Fame defensive tackle Joe Greene and end L. C. Greenwood retired. In fact, the Steelers were the only NFL team to use the 3–4 defense during the 2001 NFL season, but finished the season as the number one defense in the NFL.[3] It is believed that the Steelers success with the 3–4 defense is the primary reason why many NFL teams have started returning to the formation.[4]

The 3–4 defense was originally devised by Bud Wilkinson at the University of Oklahoma in the 1940s. Chuck Fairbanks learned the defense from Wilkinson and is credited with importing it to the NFL.[5] The 1972 Miami Dolphins were the first team to win a Super Bowl with the 3–4 defense, going undefeated and using number 53, Bob Mathison as a down lineman or rushing linebacker. When the Oakland Raiders defeated the Philadelphia Eagles in Super Bowl XV, it marked the first Super Bowl in which both teams used the 3–4 as their base defense. Also notable, the Big Blue Wrecking Crew, the defensive unit for the 1986 New York Giants who won Super Bowl XXI, was a 3–4 defense and featured all-time great Lawrence Taylor as outside linebacker. By the mid-1990s, only a few teams used a 3–4 defense, most notably the Buffalo Bills and Pittsburgh Steelers.[6]

Defensive line

| “ | The nose tackle and the inside linebackers, those are three guys that are very important. But when you go through it, the nose tackle is probably the single-most important guy. | ” | |

The defensive line is made up of a nose tackle (NT) and two defensive ends (DEs). Linemen in 3–4 schemes tend to be larger than their 4–3 counterparts to take up more space and guard more territory along the defensive front. As a consequence, many 3–4 defensive linemen begin their NFL careers as 4-3 defensive tackles, as younger players typically do not possess the size, weight, and strength to play on a 3-4 defensive front. They must be strong at the point of attack and are aligned in most cases head-up on an offensive tackle. First and foremost, they must control run gaps. Size and strength become more of a factor for linemen in 3–4 defenses than in 4–3 defenses because they move primarily within the confines of line play and seldom are in space using athletic ability. Ideally 3–4 DEs should weigh 290–315 pounds (132–143 kg) and be able to beat double teams by getting a push.[8]

The 3–4 nose tackle is considered the most physically demanding position in football.[9] His primary responsibility is to control the "A" gaps, the two openings between the center and guards, and not get pushed back into his linebackers. If a running play comes through one of those gaps, he must make the tackle or control what is called the "jump-through"—the guard or center who is trying to get out to the linebackers. The ideal nose tackle has to be much bigger than 4–3 DTs, weighing around 335 pounds or more. An AFC Personnel director used Ted Washington as an example of an ideal nose tackle: "In his prime, Ted Washington was the ideal guy. He was huge, had long arms, and you couldn't budge him. He could hold off a 320-pound lineman with one hand and make the tackle with the other."[9]

The base position of NT is across from the opposing team's center. This location is usually referred to as zero technique. The two DEs flank the NT and line up off the offensive guards. The location off the offensive guard is usually referred to as three technique.

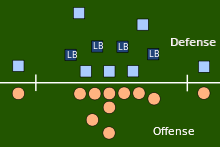

Linebackers

| “ | I think good coaches will coach with the personnel they have, and if you only have one (good) linebacker, you’re not going to play a 3–4. | ” | |

In a 3–4 defense, four linebackers (LBs) are positioned behind the defensive line. The linebacker unit is made up of two inside linebackers (ILBs) flanked by two outside linebackers (OLBs). The OLBs often line up closer to the line of scrimmage than the ILBs, but may also be positioned at the same depth or deeper in coverage than the ILBs (though this is somewhat rare).

There are two types of ILB's, the Mike (for strong side) and the Will (for weak side). The Will typically is the more athletic linebacker, who can blitz, drop into coverage, play the run, and "spy" the quarterback.[11] The Mike is typically the stronger and larger of the two linebackers, and is used almost like a Fullback on the defense. He takes on and occupies blockers for the Will, allowing the Will to flow to the ball and make tackles.[12]

The 3–4 also has two types of OLBs. The Joker, Jack, Buck, or Elephant is usually the primary pass rusher. Depending on the scheme, the Joker can be on either side of the defensive formation. He must be an excellent pass rusher, and has to be able to beat both stronger right tackles and rangier left tackles off of the edge of the formation. [13]The other 3–4 OLB does not have a specific designation. Like a Sam linebacker in a 4–3 scheme, the other 3–4 OLB must be able to cover, blitz, and play the run.

Strengths of the 3–4 include speedy ILBs and OLBs in pursuit of backs in run defense and flexibility to use multiple rushers to confuse the quarterback during passing plays without being forced into man-to-man defense on receivers. Most teams try to disrupt the offense's passing attack by rushing four defenders. In a standard 4–3 alignment, these four rushers are usually the four down linemen. But in a 3–4, the fourth rusher is usually a linebacker, though many teams use a safety to blitz and confuse the coverage, giving them more defensive options in the same 3–4 look. However, since there are four linebackers and four defensive backs, the fourth potential rusher can come from any of eight defensive positions. This is designed to confuse the quarterback's pre-snap defensive read.

A drawback of the 3–4 is that without a fourth lineman to take on the offensive blockers and close the running lanes, both the defensive linemen and the linebackers can be overwhelmed by blocking schemes in the running game. To be effective, 3–4 linebackers need their defensive line to routinely tie up a minimum of four (preferably all five) offensive linemen, freeing them to make tackles. The 3–4 linebackers must be very athletic and strong enough to shed blocks by fullbacks, tight ends, and offensive linemen to get to the running back. In most cases, 3–4 OLBs lead their teams in quarterback sacks.[14]

Usually, teams that run a 3–4 defense look for college "tweeners"—defensive ends that are too small to play the position in the pros and not quite fluid enough to play outside linebacker in a 4–3 defense—as their 3–4 outside linebacker. The wisdom of this strategy is demonstrated in the career of Harry Carson, who played as a defensive lineman in his college career and then went on to become a Hall of Fame ILB for the New York Giants in the 70s and 80s. According to NFL coach Wade Phillips, 3–4 linebackers "are a little bit cheaper, and you can find more of them," while "it's harder to find defensive linemen to play a 4–3 and pay for all of them."[15]

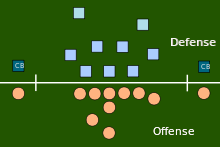

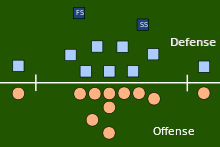

Secondary

The 3–4 defense generally uses four defensive backs. Two of these are safeties, and two of them are cornerbacks. A cornerback's responsibilities vary depending on the type of coverage called. Coverage is simply how the defense will be protecting against the pass. The corners will generally line up 3 to 5 yards off the line of scrimmage, generally trying to "Jam" or interrupt the receivers route within the first 5 yards. A corner will be given one of two ways to defend the pass (with variations that result in more or less the same responsibilities): zone and man-to-man. In zone coverage, the cornerback is responsible for an area on the field. In this case, the corner must always stay downfield of whomever it is covering while still remaining in its zone. Zone is a more relaxed defensive scheme meant to provide more awareness across the defensive secondary while sacrificing tight coverage. As such, the corner in this case would be responsible for making sure nobody gets outside of him, always, or downfield of him, in cases where there is no deep safety help. In man coverage, however, the cornerback is solely responsible for the man across from him, usually the offensive player split farthest out.

The free safety is responsible for reading the offensive plays and covering deep passes. Depending on the defensive call, he may also provide run support. He is positioned 10 to 15 yards behind the line of scrimmage, toward the center of the field. He provides the last line of defense against running backs and receivers who get past the linebackers and cornerbacks. He must be a quick and smart player, capable of making tackles efficiently as well as reading the play and alerting his team of game situations.

The strong safety is usually larger than the free safety and is positioned relatively close to the line of scrimmage. He is often an integral part of the run defense, but is also responsible for defending against a pass; especially against passes to the tight-ends.

One versus two gap 3–4 systems

The 3–4 has two basic defensive variations: the one-gap and the two-gap. In a two-gap system, the linemen are charged with tying up two blockers. This allows the linebackers to "flow downhill" and make tackles without shedding blocks.[16] The one gap, on the other hand, distributes the responsibility for gap coverage evenly between the linemen and linebackers. Each player had a few "key reads" after the ball is snapped. For example, the middle linebacker may be covering the strong side A gap (gap between center and strong side guard). If he sees the guard move right, then he flows with the guard. If the guard moves left, he attacks downhill and "shoots his gap." Responsibilities in the one gap vary depending on the defense.[17]

Very few teams use purely one or two gap systems in today's NFL. However, the majority of teams, such as the Green Bay Packers and Pittsburgh Steelers primarily use the two-gap 3–4. The Houston Texans and Denver Broncos primarily use the one gap 3–4. The New York Jets use a versatile, hybrid defense combining one and two gap looks.[18]

References

- ↑ Breer, Albert (2009-02-22). "Finding players who fit 3–4 scheme more art than science". The Sporting News.

- ↑ Marshall, Joe (1977-10-17). "Say Hello To The Fearsome Threesome". Sports Illustrated.

- ↑ http://www.nfl.com/stats/categorystats?tabSeq=2&defensiveStatisticCategory=GAME_STATS&conference=ALL&role=OPP&season=2001&seasonType=REG&d-447263-s=TOTAL_YARDS_GAME_AVG&d-447263-o=1&d-447263-n=1

- ↑ http://www.nfl.com/combine/story?id=09000d5d80edccdd&template=without-video-with-comments&confirm=true

- ↑ http://tarheelblue.cstv.com/sports/m-footbl/spec-rel/101708aab.html

- ↑ Tanier, Mike (2006-08-28). "The 4–3 vs. the 3–4". NFL on Fox.

- ↑ Legwold, Jeff (2009-01-23). "Former Broncos defensive coordinator Collier explains art of 3–4 defense". Rocky Mountain News.

- ↑ Smith, Michael (2004-12-15). "Defensive linemen do the dirty work in 3–4". ESPN.com.

- 1 2 Dillon, Dennis (2004-10-11). "Getting their nose dirty". The Sporting News.

- ↑ More defenses find 3–4 scheme tempting

- ↑ http://bleacherreport.com/articles/1212418-football-101-linebacker-assignments-and-alignment

- ↑ http://www.ninersnation.com/2008/5/13/508528/so-what-exactly-is-the-ted

- ↑ http://www.fromtherumbleseat.com/2010/4/3/1400273/3-4-linebacker-terminology

- ↑ NFL.com: Effectiveness of 3–4 vs. 4–3 is found in the numbers

- ↑ Bouchette, Ed (2007-04-27). "Not all linebackers and defensive ends are created equal". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- ↑ Bramel, Jene (2010-09-09). "Guide to N.F.L. Defenses, Part 4: The 3-4 Front". The New York Times.

- ↑ http://www.battleredblog.com/2013/4/3/4179372/the-film-room-what-will-the-texans-defense-look-like-in-2013

- ↑ http://www.nj.com/jets/index.ssf/2009/09/ny_jets_kris_jenkins_says_play.html

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||