2nd Battalion (Australia)

| 2nd Battalion | |

|---|---|

|

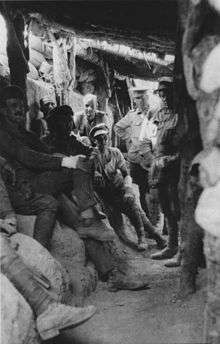

Officers from the 2nd Battalion at Giza, December 1914 | |

| Active |

1914–19 1921–29 1939–43 1948–60 1965–87 |

| Country | Australia |

| Branch | Australian Army |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | ~1,000 men[Note 1] |

| Part of |

1st Brigade 8th Brigade |

| Nickname(s) | City of Newcastle Regiment |

| Motto | Nulli Secundus (Second To None) |

| Colours | Purple over Green |

| March | Braganza |

| Engagements |

First World War Second World War |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders |

George Braund Thomas Blamey |

| Insignia | |

| Unit Colour Patch |

|

| Abbreviation | 2 RNSWR |

The 2nd Battalion was an infantry battalion of the Australian Army. It was initially raised for service during the First World War as part the Australian Imperial Force and saw action at Gallipoli before being sent to the Western Front in mid-1916, where it spent the next two-and-a-half years taking part in the fighting in the trenches of France and Belgium. Following the conclusion of hostilities, the battalion was disbanded in early 1919 as part of the demobilisation process.

In 1921, the battalion was re-raised as a part-time unit of the Citizens Forces based in Newcastle, New South Wales, drawing lineage from a number of previously existing infantry units. They remained in existence until 1929 when, due to austerity measures during the Great Depression and manpower shortages, the battalion was amalgamated with two other infantry battalions over the course of a number of re-organisations. It was re-formed in 1939 and undertook garrison duty in Australia during the Second World War until 1943 when it was merged once again.

Following the end of the war, the 2nd Battalion was re-raised as part of the Citizens Military Force in 1948. In 1960, it was reduced to a company-level formation but was re-formed as a battalion of the Royal New South Wales Regiment in 1965. It remained on the Australian order of battle until 1987 when it was amalgamated with the 17th Battalion, to form the 2nd/17th Battalion, Royal New South Wales Regiment, a unit which remains part of the Australian Army Reserve today.

History

First World War

Formation and training

The 2nd Battalion was raised at Randwick, New South Wales, in August 1914 as part of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF), which was formed from volunteers for overseas service shortly after the outbreak of the First World War.[2] Drawing the majority of its personnel from the Maitland, Newcastle and Hunter Valley regions of the state of New South Wales,[3][4] the battalion formed part of the 1st Brigade and, along with the 1st, 3rd and 4th Battalions,[5] it was one of the first infantry units raised by Australia following its entry into the war.[6] Upon formation, the battalion was established with a complement of over 1,000 men organised into a headquarters, a machine-gun section of two heavy Maxim medium machine-guns, and eight rifle companies, each consisting of three officers and 117 other ranks.[7][8] The battalion's first commanding officer was Lieutenant Colonel George Braund,[6] a citizen soldier and Member of Parliament in the New South Wales Legislative Assembly, who held the seat of Armidale.[9]

The physical standards under which the first contingent of the AIF was recruited were very strict, nevertheless by the end of August over 20,000 men had been recruited into one infantry division—the 1st Division—and one light horse brigade, the 1st Light Horse Brigade.[10] Following a brief period of training in Australia, the force set sail for the Middle East, assembling off Albany, Western Australia, in early November 1914 before leaving Australian waters,[11] with the 2nd Battalion embarked upon the HMAT Suffolk.[12]

Initially it had been planned that the Australians would be sent to the United Kingdom, where they would undertake further training prior to being sent to the Western Front in France and Belgium. However, the Ottoman Empire's entry into the war on Germany's side on 29 October meant that the strategically vital Suez Canal was threatened, and as a result of this and overcrowding in training grounds in the United Kingdom, upon the convoy reaching the Suez at the end of November, plans for the use of the Australian force were changed and they were disembarked in Egypt instead.[13]

The 2nd Battalion arrived in Egypt on 2 December.[6] The following month, it undertook further training along with the rest of the 1st Division. The battalion was also re-organised into four companies,[14] as the Australian Army converted to the new battalion structure that had been developed by the British Army. Although the battalion's authorised strength remained the same, the eight companies were merged into four, each consisting of six officers and 221 other ranks.[8]

In February 1915, Ottoman Empire forces attacked the Suez Canal,[15] and although some units of the 1st Division were put into the line,[Note 2] the 2nd Battalion was not required, and in the end the attack was turned back mainly by Indian units.[16] Later, in an effort to open shipping lanes to the Russians and also knock the Turks out of the war, the British high command decided to land a force on the Gallipoli peninsula near the Dardanelles using mainly British, French and Indian troops along with the Australians and New Zealanders.[17]

Gallipoli

During the Landing at Anzac Cove on 25 April 1915, the 2nd Battalion, under Braund's command, came ashore in the second and third waves,[6] landing a total of 31 officers and 937 other ranks.[18] Upon landing, the 2nd Battalion dispatched two companies, 'A' and 'D' to assist the 3rd Brigade who were pushing inland towards a high feature known as "Baby 700", which overlooked the beachhead.[19] One of the 2nd Battalion's platoons, under Lieutenant Leslie Morshead, advanced further than any other Australian unit, making it to the slopes of Baby 700, before a determined counter-attack by Ottoman forces drove them back in the afternoon.[20]

Meanwhile, the battalion's other two companies, 'B' and 'C', had been held back in reserve. In the early afternoon, Braund led them up the steep terrain under fire to the vital junction between two positions known as "Walker's Ridge" and "Russell's Top". The battalion proceeded to hold this position until reinforcements arrived from the Wellington Battalion two days later, at which time the 2nd Battalion undertook a bayonet charge which cleared the crest of Russell's Top.[21] A determined enemy counter-attack forced them back to the junction where they remained until 28 April when they were ordered into reserve on the beach.[21]

In early May, part of the battalion was sent to reinforce the 3rd Battalion. At around midnight on the night of 3/4 May, the 2nd Battalion's commanding officer, Braund, who was partially deaf, was accidentally killed as he attempted to visit 1st Brigade headquarters after failing to hear a challenge from a sentry, who shot him believing that he was an enemy soldier.[21] Following his burial, the battalion second-in-command, Robert Scobie, was promoted to lieutenant colonel and took over as commanding officer.[6]

Following the initial establishment of the beachhead, the campaign moved into a second phase as the Australians began work to consolidate and slowly expand their position around the lodgement.[22] During this time, the fighting at Anzac evolved into largely static trench warfare.[23] In mid-May, however, the Turks decided to launch an attack on Anzac. This began late on 18 May with the heaviest artillery bombardment of the campaign to that point, during which the 2nd Battalion's orderly room, located on "MacLaurin's Hill", was hit.[24] The assault began the following day, during which the 2nd Battalion, established around a position known as the "Pimple", was attacked by elements of the Ottoman 48th Regiment who poured into their forward positions through "Owen's Gulley", which rose as a re-entrant between the 2nd Battalion's position and that of 3rd Battalion which was on their left at the "Jolly".[25] At risk of having the line split in two and enduring heavy attack in their sap head, the 2nd called for reinforcements which came in the shape of artillerymen from the 8th Battery, who were pressed into the line as infantrymen.[26] With only limited machine-guns and with bad light hindering the supporting artillery, the job of turning back the Turkish assault fell to the riflemen and by maintaining strict fire discipline, great effect was achieved.[27] By 24 May, the attack had been decisively defeated and a brief truce was called for both sides to bury the dead. Following this, the Ottoman forces around Anzac adopted a defensive posture.[28] It was during this time, that one of the 2nd Battalion's soldiers, Lance Corporal (later Sergeant) William Beech, invented the periscope rifle.[29]

In early August, in order to create a diversion to draw Ottoman reserves away from a major attack at Hill 971, which had been conceived as part of an attempt to break the stalemate that had developed around the beachhead, the 1st Brigade conducted an attack at Lone Pine.[30] The 2nd Battalion was chosen to take part in the initial assault.[31] After gaining possession of the main enemy line, the Australians were subjected to a series of determined counter-attacks which would last the next three days, which, although successfully repulsed, proved very costly for the Australians.[32] The 2nd Battalion suffered considerably. Having started the action with 22 officers and 560 other ranks, they lost 21 officers and 409 other ranks killed or wounded.[33] Among those killed was its commanding officer, Scobie, who was shot dead while attempting to repulse a counter-attack on 7 August.[34] In Scobie's place, the battalion second-in-command, Major Arthur Stevens, who had been a second lieutenant less than 12 months before, took over as temporary commander.[35]

Elsewhere, the main offensive which had been launched at Hill 971 and Sari Bair, and the fresh landings that had taken place at Suvla Bay, also faltered. Ultimately, the August Offensive, of which the fighting at Lone Pine had been a part, failed to deliver the Sari Bair heights to the British Empire forces and their allies,[36] nor did it break the deadlock. Following this, stalemate returned to the peninsula during September and October, and although small skirmishes continued, the Australians were mainly involved in defensive actions.[37] As a result of the setback, many of the strategic goals that had been the basis of the campaign were abandoned and as a bitter winter set-in in November, there was much debate among the British high command about the utility of continuing the campaign.[38] In the intervening months, some personnel had been shifted away from Gallipoli as other the situation in other theatres became more relevant, and in late November, Lord Kitchener toured the peninsula.[36] Finally, on 8 December, the order to begin the evacuation was given.[39] The evacuation, which has been described as "more brilliantly conducted ... than any other phase of the campaign",[40] took place in stages, and with the maintenance of secrecy a key consideration, a series of "ruses" were used to conceal the withdrawal. Each unit left in drafts, maintaining a presence along the line until the very end. Finally, just before dawn on 20 December, the evacuation was complete.[41] A small element from the 2nd Battalion was among the last Australian troops to leave, with a group of 64 men remaining in possession of the "Black Hand" position until 2:50 am on the final morning.[42]

Egypt

Following the withdrawal from Gallipoli, the AIF returned to Egypt where they underwent a period of re-organisation.[43] Part of this saw the influx of large numbers of reinforcements and the expansion of the AIF. The 2nd Division had been formed in July 1915, and part of this had been dispatched to Gallipoli in the later stages of the campaign, but the large increase in volunteers in Australia meant that further plans for expansion could take place. The 3rd Division was raised in Australia, while two new divisions, the 4th and 5th Divisions, were raised in Egypt from reinforcements in holding depots and experienced cadre personnel which were drawn from the infantry battalions of the 1st Division.[44] In this regard, the 1st Brigade helped raise the 14th Brigade, with personnel from the 2nd Battalion being transferred to the 54th Battalion;[45] the split occurring while the battalion was at Tel el Kebir on 14 February. They were quickly brought up to full strength and training began shortly afterwards.[46]

Earlier in the month, Stevens was promoted to lieutenant colonel and placed in substantive command of the battalion; he would subsequently lead them through to November 1916.[35] Around this time, the units of the 1st Division, of which the 2nd Battalion was a part, became part of the larger I Anzac Corps, and in early March, this corps embarked for France – the 2nd Battalion leaving from Alexandria on the SS Ivernia[47] – where they were to take part in the fighting on the European battlefield.[48]

Western Front

After being landed in Marseilles,[49] they proceeded north by railway to staging areas near Hazebrouck.[50] Shortly afterwards, on 7 April, the units of I Anzac Corps were assigned to a "quiet" sector of the line near Armentières to gain experience of trench warfare.[51] Due to concerns about a German attack, almost immediately the Australians set to work to improve the defences around their position.[52] It had been hoped by the high command to initially keep the Australian presence a secret in order to gain some advantage from it, however, on 23 April it became apparent that the Germans had become aware of their arrival when a signal lamp flashed a message in Morse code from the trench opposite the 2nd Battalion's position stating, "Australians go home". To this, the Australians, despite orders against responding, replied matter-of-factly, "Why?"[53]

In June, during a brief period away from the line in billets, the battalion, along with the rest of the 1st Brigade, was reviewed by the Australian prime minister, Billy Hughes near Fleurbaix.[54] Following this, although several units from I Anzac Corps took part in a number of raids against the German line during late June and early July,[55] the 2nd Battalion was not involved and as such, apart from experiencing some enemy shelling, the 2nd Battalion's first significant action came at Pozières in July 1916.[6] The battalion entered the line on the night of 19/20 July as the 1st was sent forward to relieve the British 68th Brigade along with the 3rd Brigade;[56] just after midnight the 2nd Battalion, after an approach march over which they had endured gas attack, arrived at its position opposite the south-western side of the village.[57]

On 23 July, following an intense artillery barrage,[58] the attack began. Leaving their form-up point near the "Chalk Pit", the 2nd Battalion, which had been allocated the position of the left forward battalion in the assault with the 1st Battalion on their right and the 4th Battalion following them up,[59] moved out into no man's land just after midnight. A short time afterwards a flare was fired from the German lines followed by sporadic rifle and machine-gun fire, which was directed somewhere away from the battalion's axis-of-advance. As they advanced over the broken ground, suddenly a sentry called out a challenge and the entire battalion froze, but when firing broke out it became clear that it was directed away to their right towards the 3rd Brigade who were advancing over open ground.[60] Advancing beneath the supporting barrage, under the direction of their officers whose job it was to ensure that they did not get ahead of the creeping artillery, the battalion probed forward trying to locate the enemy defences, finally finding an abandoned trench located amongst a group of tree stumps.[61] After striking the railway, they began to dig-in just beyond it to secure the left flank, as the 3rd and 4th Battalions passed between them and advanced to secure the brigade's front along the line of the main Bapaume road. Following this, the 2nd Battalion maintained the left-most position on the brigade line, with its pits curling around the left flank and folding in behind the 4th Battalion's position.[62]

The Germans put in a determined counter-attack at dawn with a whole battalion, which was turned back after a stiff fight. That night, reinforcements were brought up from the 2nd Brigade, and early in the morning on 24 July the Germans opened up with a devastating artillery barrage.[63] On 25 July, the men of the 2nd Battalion, having suffered terribly in the open trenches, were relieved by the 7th Battalion.[64] During the operations around Pozières, the battalion lost 10 officers and 500 men killed or wounded.[35][65]

.jpg)

After this, they were sent to Pernois for rest and re-organisation,[66] and after being brought back up to about two-thirds strength,[67] the 2nd Battalion's next involvement in the fighting came around Mouquet Farm when they were briefly put into the line on 18/19 August to provide reinforcement, before being quickly relieved a few days later.[68] In early September, I Anzac Corps was transferred from the Somme region to Ypres, in Belgium, swapping with the Canadians for a rest.[69] Taking up a position north of the Ypres–Commines canal, the battalions of the 1st Division were placed in the centre of the line between those of the 4th, on the right to the south, and the 2nd on the left, to the north.[70] The sector was a relatively quiet one, although not without its dangers due to constant mortar attacks, sniping, and the need to maintain patrols in no man's land.[71] Nevertheless, duties in this time were focused mainly upon maintaining a defensive presence in the line and rebuilding the defences. In addition, a number of small-scale raids were also undertaken in an effort to draw some attention away from the fighting that was occurring on the Somme.[70]

On 6 October, in concert with three parties from the 1st Battalion, the 2nd carried out a minor raid on a German position to the north-east of a position known as "The Bluff" in order to gain intelligence. After encountering a German patrol, they were forced to abandon their attempt, however, a short time later, one of their own patrols captured a German soldier from the 414th Infantry Regiment in no man's land.[72] The next week, on 12 October, just after 6:00 pm a small party moved out into no man's land to raid another German position near The Bluff. After being spotted, they were subjected to several grenade attacks, forcing them to retire. Their covering force was already in position, however, and so a number of the attacking force joined them and together, at 6:30 pm, after a box barrage by the artillery had cut the wire in front of the German position, they entered it. Killing seven Germans, they overcame the enemy resistance and brought back two defenders as prisoners. On the way back, several of their own wounded became lost, although all except one of these men were later recovered. The other man, one of the officers, was later found to have died of his wounds. In total the raid had cost the battalion two killed and seven wounded.[73]

After this, the units of I Anzac Corps returned to the Somme, to relieve units of the Fourth Army, which had managed to push their lines to a position just below the Bapaume heights throughout September.[74] The 2nd Battalion was not involved in any major actions during this time, although elements from the 1st Brigade—specifically the 1st Battalion with support from the 3rd—put in an attack on a salient that had developed in the front line north of Gueudecourt, which failed amid exceptionally muddy conditions.[75]

Winter began to set in at this point, and even though combat operations all but ceased during this time, the battalion endured considerable hardships amid snow and rain, in a sector that has been described as "the worst ... of the sodden front".[76] For a brief period during December, Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Blamey commanded the battalion before taking over as acting commander of the 1st Brigade.[77] During this time, the battalion was reorganised as part of a wider-Army restructure that resulted in an attempt to increase the firepower of the each platoon. Earlier in the year, the battalion machine-gun section had been deleted and replaced by a single Lewis gun held within each company; by end of the year this had been increased to one Lewis per platoon.[78]

As 1917 began with the Allies making fresh plans, the Germans, finding themselves outnumbered and needing to shorten their lines, began a skilful staged withdrawal beginning in February and ending in April.[79] Falling back up to 31 miles (50 km) in some places, they took up positions along a series of heavily fortified, purpose-built strong-points which the Allies subsequently named the "Hindenburg Line", which, due to the reduced frontage, enabled them to free up some 13 divisions of reserves.[80] Following up the Germans, the Allies advanced towards this line, finding that the Germans had adopted a scorched earth policy as they had moved back; the result of this was that in order to establish their own lines, the Allies had to undertake significant construction work.[80]

Due to the shifting front line, the 2nd Battalion's first major engagement of 1917 did not come until 9 April when, on the periphery of the Arras offensive, they took part in an attack on Hermies, one of the outpost villages of the Hindenburg Line.[81] Under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Stanley Milligan, who had taken over on 17 March,[82] the battalion had departed Haplincourt at 7:30 pm the previous evening and marched to their form-up point. The plan was to attack with the battalion's four companies advancing side-by-side from the north-east to attack from behind the German defences, sweeping down on the village like a fan with the left-most company providing flank protection and establishing a series of posts to stop the garrison from escaping while the two centre and the right-most companies took the village. At the same time, two companies from the 3rd Battalion would attack the German main defensive position from the south-west.[83]

In the end, the Australians were detected while waiting to step off and, after being illuminated by flares and taking fire from a German picquet, hastily launched the attack.[84] After overcoming this, the left-centre company, having lost all of their officers, lost their formation and had to be re-organised before the attack on the eastern side of the village could continue. The two companies passed through hedges and the ruined buildings, clearing the outskirts of the village with little resistance. The left-most company then began its task of establishing outposts to the east.[85] At the same time, on the right, the right-most company had advanced to the Doignes–Hermies road when they had begun to take fire. Overcoming this and skirting a wire obstacle, they began moving towards the rear of the German main defence line. At this point, they came under fire from a low hill on the western outskirts of the village, which took them in the flank and pinned them on its slope. In the darkness, the location of the enemy machine-gun could not be ascertained initially. The Australians remained fixed there for almost an hour-and-a-half before members of the right centre company, who had avoided most of the German resistance, were able to locate it and destroy it from the rear just before dawn.[86] The two centre companies were then able to enter the village proper, forcing large numbers of the garrison to try to escape to the north-east, where they were taken prisoner in large numbers.[87] Here the left-most company had been establishing a number of posts in the open fields. Most of these were established with minimal resistance, however, one platoon became heavily engaged by a machine-gun positioned near a sandpit on the other side of a road. A small group of men crossed the road and attempted to provide covering fire for the platoon. Amongst this group was Private Bede Kenny who, under heavy fire, rushed the enemy position and destroyed it with grenades, taking the surviving Germans prisoner. For his actions, he was later awarded the Victoria Cross.[88][89] Minor skirmishing continued after this, but by 6:00 am the village had been captured and 200 prisoners taken, for a loss to the 2nd Battalion of eight officers and 173 other ranks killed or wounded.[90]

The battalion played only a limited, supporting role during the 1st Division's repulse of the German counter-attack at Lagnicourt in mid-April,[91] and following this the battalion's next major action came in early May when it was involved in the Second Battle of Bullecourt.[82] The day before the attack, the battalions of the 1st Brigade, despite being due for rest, had been attached to the 2nd Division, and they were subsequently employed to provide work parties to release reserves among the 2nd Division units to take part directly in the fighting.[92] Having not yet recovered its losses from the fighting around Hermies, and being subjected to artillery bombardment during their approach to the front, the 2nd Battalion entered the line on 4 May with just 16 officers and 446 other ranks,[93] subsequently relieving the 24th Battalion.[94] As the Germans attempted to force the Australians back, the 2nd Battalion was moved around a number of times to shore up the line,[95] until units of the 5th Division came up to relieve those of the 1st Brigade on 8 May.[96]

The battalion's next major action came in mid-September when they were committed to the fighting around Menin Road, which formed part of the wider Third Battle of Ypres, in a supporting role. On 16 September, the battalions of the 1st Brigade relieved the 47th (London) Division around Glencourse Ridge,[97] located about 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) east of Ypres,[98] holding the line until relieved on 18 September by the 2nd and 3rd Brigades who were to undertake the assault within the 1st Division's sector of the line.[97] Following the assault, the 1st Brigade, including the 2nd Battalion, went forward on 21 September and secured the ground that had been gained. They were subsequently relieved shortly afterwards on the night of 22/23 September by troops from the 14th Brigade,[99] as fresh divisions were brought up to continue the attack at Polygon Wood.[98][100] The battalion's casualties during this time amounted to 11 officers and 188 other ranks killed or wounded.[101]

After a brief period of rest, they returned to the line near Broodseinde on 1 October,[102] taking up a position near Molenaarelsthoek, on the right of I Anzac's position for the upcoming battle.[103] The attack went in on 4 October, and after overcoming an encounter with a German infantry regiment, the 212th, in no man's land, the Australians successfully managed to capture their objectives.[104] During the battle, the 2nd Battalion lost 10 officers and 144 other ranks killed or wounded,[105] some of which were suffered after an intense German mortar barrage had fallen upon the troops in their form-up point prior to the attack, killing or wounding up to one seventh of the assault force.[106]

On 19 December 1917, after the battalion had moved to the relatively quiet Messines sector in Flanders along with the other Australian divisions following their involvement in the Passchendaele operations,[107] Stevens resumed command;[35] Milligan having been elevated to the general staff.[82] Stevens would subsequently lead them through until September 1918 when he was granted "Anzac leave" which allowed personnel who had enlisted in 1914 to return Australia for an extended period of leave.[35]

Throughout the winter, the Australian divisions remained around Messines, where they had been formed into the Australian Corps.[108] During this time, the brigades rotated through the line, taking their turn to man the divisional sector. The 2nd Battalion had spent Christmas at Kemmel before moving on to Wytschaete Ridge on 26 December. They stayed there until late January when they moved on to Méteren.[109] In early 1918, the collapse of the Russian resistance on the Eastern Front enabled the Germans to transfer a large number of troops to the west.[Note 3][110] As a result, on 21 March, they launched an offensive along the Western Front.[111] On the opening day of the offensive, the 2nd Battalion's lines near Belgian Wood were raided by the 72nd Infantry Regiment and although the attack was beaten off, four men from the battalion were forcibly taken back to the German lines as prisoners.[112] The initial attack, coming along a 44-mile (71 km) front between La Bassée and La Fère,[111] was quite successful and with the Germans making rapid gains, the Australians were transferred to the Somme Valley where they were put into the line around Amiens to blunt the attack in early April.[113][114]

Shortly thereafter, during the Battle of the Lys, the 2nd Battalion, along with the rest of the 1st Division, were sent to Hazebrouck.[115] Upon arriving there on 12 April, they took up defensive positions around Strazelle to await the German advance.[116] On 17 April, while defending the village of Sec Bois, the battalion helped turn back a determined German attack.[117]

Following this, between late April and July, a period of lull followed.[113] During this time, the Australians undertook a series of small-scale operations that became known as "peaceful penetrations". After relieving the 3rd Brigade around Méteren on 27 April, the battalions of the 1st Brigade began patrols on 30 April to capture German soldiers to gain intelligence and harass the enemy.[118] These were generally met with considerable success, although they were not without mishap. Two separate patrols were undertaken by the 2nd Battalion on 2 May. The first resulted in one officer being shot while attempting to enter a German trench, while the second resulted in another being shot by an Australian sentry who had not been warned that a patrol had gone out.[119] Later in May, they took up a position opposite Merris, remaining there until the end of the month.[120] Throughout June and July they alternated between Meteren and Merris during which time they continued to raiding operations, which advanced the line about 1,000 yards (910 m) without significant loss.[121]

.jpg)

In August, having gained the initiative, the Allies launched their own offensive commencing at Amiens on 8 August 1918, where the battalions of the 1st Brigade were attached temporarily to the 4th Division, to act as its reserve,[122] guarding the river crossing at Cerisy.[123] Following this they were involved in the advance through Chipilly and Lihons,[124] remaining in reserve until 11 August.[125] Throughout the period of the first week of the offensive, the battalion suffered three officers and 45 other ranks killed or wounded.[126]

After this, the battalion continued operations throughout August and into September. On the night of 10/11 September, while around Hesbécourt,[127] the 2nd Battalion carried out peaceful penetration raids against German reserve positions around Jeancourt. Finding the village empty, they encountered a German patrol from the 81st Infantry Regiment, which was attacked and quickly overwhelmed.[127] At noon the following day, they launched a larger attack with artillery and mortar support, destroying two German outposts to the south of the village, killing eight Germans and capturing 22 others.[128] In their last action, against the Hindenburg Outpost Line on 18/19 September, the battalion suffered a further 77 casualties.[129]

On 23 September the battalion was relieved by American forces.[130] At this time they were withdrawn from the line along with the rest of the 1st Division.[131] They would take no further part in the fighting.[6] In early October, the rest of the Australian Corps, severely depleted due to heavy casualties and falling enlistments in Australia, was also withdrawn upon a request made by Prime Minister Billy Hughes, to re-organise in preparation for further operations.[132] On 11 November, an armistice came into effect, and as hostilities came to an end, the battalion's personnel were slowly repatriated back to Australia for demobilisation and discharge. This was completed in May 1919.[6]

Throughout the war, the 2nd Battalion lost 1,199 men killed and 2,252 wounded. Members of the battalion received the following decorations: one Victoria Cross, four Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George, 20 Military Crosses, 21 Distinguished Conduct Medals, 58 Military Medals with two Bars, four Meritorious Service Medals, 55 Mentioned in Despatches and five foreign awards.[6]

Inter war years and the Second World War

The battalion was re-raised in Newcastle, New South Wales, in May 1921 as part the re-organisation of the Australian military that took place at that time,[133] with the battalion becoming a part-time unit of the Citizens Forces, assigned to the 8th Brigade of the 2nd Military District.[134][135] Upon formation, the battalion drew its personnel from three previously existing Citizens Forces units: the 2nd and 5th Battalions of the 2nd Infantry Regiment and the 2nd Battalion of the 13th Infantry Regiment,[136][137] and perpetuated the battle honours and traditions of its associated AIF battalion.[133][138] As a result of this re-organisation, the battalion adopted the complex lineage of the 2nd Infantry Regiment, which could trace its history through a series of re-organisations back to the 1st Regiment, New South Wales Rifle Volunteers (Newcastle Volunteer Rifle Corps), which had been raised in 1860.[139]

In 1927, territorial unit titles were introduced into the Australian Army,[138] and the battalion adopted the title of the "City of Newcastle Regiment".[139] At the same time, the battalion was afforded the motto Nulli Secundus.[140] In 1929, following the election of the Scullin Labor government, the compulsory training scheme was suspended altogether as it was decided to maintain the part-time military force on a volunteer-only basis.[141] In order to reflect the change, the Citizen Forces was renamed the "Militia" at this time.[142] The end of compulsory training and the fiscal austerity that followed due to the economic downturn of the Great Depression meant that the manpower available to many Militia units at this time was limited and as a result their frontage dropped well below their authorised establishments. Because of this, the decision was eventually made to amalgamate a number of units.[143] Subsequently the 2nd Battalion was amalgamated with the 41st in 1929, forming the 2nd/41st Battalion, although they were later split in 1933 at which time the 2nd was merged with the 35th, becoming the 2nd/35th Battalion.[136][139]

Together these two units remained linked until 4 September 1939 when, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel William Jeater,[144] the 2nd Battalion was once again raised as a separate unit[139][145] as part of an effort by the Australian government to hastily expand the Militia following the outbreak of the Second World War.[146] During the war, although mobilised and assigned to the 1st Brigade,[147] the battalion did not see active service overseas and was instead used as a garrison force in Australia until 2 December 1943 when it was merged once again with the 41st Battalion, forming the 41st/2nd Battalion.[145] They remained linked until 17 December 1945, when they were disbanded as part of the demobilisation process.[136][137]

Post Second World War

In 1948, Australia's part-time military force, under the guise of the Citizens Military Force (CMF), was re-raised. At this time, only two divisions were formed along with other supporting units.[148] The 2nd Battalion was one of those units that was re-established, returning to the order of battle in April 1948,[137] as part of the 2nd Division.[149]

Between 1951 and 1960 a national service scheme had operated and during this time the CMF's numbers remained reasonably steady. However, in 1960 the scheme was suspended and the Australian Army was reorganised with the introduction of the Pentropic divisional structure.[150] As a result of this the CMF was greatly reduced and 14 infantry battalions were disbanded altogether, while many others were amalgamated into the battalions of the six sequentially numbered multi-battalion State-based regiments.[150] As a result of this, on 1 July 1960, the 2nd Battalion became part of the Royal New South Wales Regiment, and was reduced to a company-sized element of the Pentropic 2nd Battalion, Royal New South Wales Regiment (2 RNSWR), forming 'C' Company (City of Newcastle Company).[4][151][Note 4] Just prior to this, on 30 April 1960, the battalion had been afforded the Freedom of the City of Newcastle.[137][140]

In 1961, the Pentropic 2 RNSWR was entrusted with the battle honours that had been awarded to the 2/2nd Battalion, which had been raised as part of the Second Australian Imperial Force and which had served in North Africa, Greece, Crete and New Guinea.[4][152] These honours would be retained by the 2nd Battalion throughout the rest of its existence.[136]

The Australian Army abandoned the Pentropic divisional structure in 1965, and in an attempt to restore some of the regional ties of the State-based regiments, a number of the regional companies of the State-based regiments were split and used to form new battalions with their traditional numerical designations. As a result, on 1 July 1965, 'C' Company, 2 RNSWR was used to re-raise the 2nd Battalion in its own right.[4] This unit remained in existence until 1987, when further reforms to the Army Reserve led to a reduction in the number of infantry units across Australia and, at a ceremony held at Newcastle on 5 December 1987,[153] the 2nd Battalion was amalgamated with the 17th to form the 2nd/17th Battalion, Royal New South Wales Regiment,[4][154] within the 8th Brigade.[155] Before amalgamation, the battalion's regimental march was Braganza, which was confirmed in 1953.[140]

Alliances

The 2nd Battalion held the following alliances:[137][140]

- United Kingdom – The Queen's Royal Regiment (West Surrey): 1929–59;

- United Kingdom – The Queen's Royal Surrey Regiment: 1959–60;

- Canada – The Queen's Rangers (1st American Regiment): 1934–36;

- Canada – The Queen's York Rangers (1st American Regiment): 1936–60.

Battle honours

The 2nd Battalion received the following battle honours:

- First World War: Somme 1916–18, Pozières, Bullecourt, Ypres 1917, Menin Road, Polygon Wood, Broodseinde, Poelcappelle, Passchendaele, Lys, Hazebrouck, Amiens, Albert 1918 (Chuignes), Hindenburg Line, Epehy, France and Flanders 1916–18, ANZAC, Landing at ANZAC, Defence at ANZAC, Suvla, Sari Bair–Lone Pine, Egypt 1915–16, and Herbertshohe.[6][Note 5]

- Second World War: But–Dagua, North Africa, Bardia 1941, Capture of Tobruk, Greece 1941, Mount Olympus, Tempe Gorge, South-West Pacific 1942–45, Kokoda Trail, Eora Creek–Templeton's Crossing II, Oivi–Gorari, Buna–Gona, Sanananda Road, Liberation of Australian New Guinea, and Nambut Ridge.[152][Note 6]

Commanding officers

The following officers served as commanding officer of the 2nd Battalion during the First World War:[6]

- Lieutenant Colonel George Braund;

- Lieutenant Colonel Robert Scobie;

- Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Stevens;[35]

- Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Blamey;[77][156]

- Lieutenant Colonel Stanley Milligan.[82]

Lineage

The following represents the 2nd Battalion's lineage:[136][139][153]

- 1860–70: 1st Regiment, NSW Rifle Volunteers (Newcastle Volunteer Rifle Corps);

- 1870–76: The Northern Battalion Volunteer Rifles;

- 1876–78: The Northern Rifle Regiment;

- 1878–84: New South Wales Volunteer Infantry, Northern District;

- 1884–1901: 4th Admin Regiment, NSW Volunteer Infantry Northern Districts;

- 1901–03: 4th Infantry Regiment;

- 1903–08: 4th Australian Infantry Regiment;

- 1908–12: 1st Battalion, 4th Australian Infantry Regiment;

- 1912–14: 16th Infantry (Newcastle Battalion);

- 1914: 2nd Battalion (AIF) raised;

- 1915–18: 15th Infantry;

- 1918–19: 2nd Battalion, 2nd Infantry Regiment;

- 1919: 2nd Battalion (AIF) disbanded;

- 1921–27: 2nd Battalion;

- 1927–29: 2nd Battalion (The City of Newcastle Regiment);

- 1929–33: 2nd/41st Battalion;

- 1933–39: 2nd/35th Battalion;

- 1939–43: 2nd (The City of Newcastle) Battalion;

- 1939: 2/2nd Battalion (2nd AIF) raised;

- 1943–45: 41st/2nd Australian Infantry Battalion (AIF);

- 1945–46: 41st/2nd Australian Infantry Battalion (AIF) and 2/2nd Battalion (2nd AIF) disbanded;

- 1948–60: 2nd Infantry Battalion (The City of Newcastle Regiment);

- 1960–65: 'C' Company (City of Newcastle Company), 2nd Battalion, The Royal New South Wales Regiment;

- 1965–87: 2nd Battalion, The Royal New South Wales Regiment;

- 1987–present: 2nd/17th Battalion, The Royal New South Wales Regiment.

Notes

- Footnotes

- ↑ During the First World War, the authorised strength of an Australian infantry battalion was 1,023 men.[1]

- ↑ The 7th and 8th Battalions from the 2nd Brigade were dispatched to man defensive positions.[16]

- ↑ At 30 November 1917, there were 160 German divisions on the Western Front. Following the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, this rose to 208.[110]

- ↑ This battalion consisted of five companies, each of which had been formed from a battalion-level formation. The other battalions which had been merged into 2 RNSWR were: the 30th Bn (The New South Wales Scottish Regiment) which provided 'A' Coy (The New South Wales Scottish Coy); the 17th/18th Bn (The North Shore Regt) which provided 'B' Coy (The North Shore Coy); the 13th Bn (The Macquarie Regt) which provided 'D' Coy (The Macquarie Coy); and the 6th New South Wales Mounted Rifles which provided 'E' Coy (The Mounted Rifles Coy) and Spt Coy (The Kuring Gai Coy).[151]

- ↑ Awarded in 1927. The award of "Herbertshohe" was made because many 2nd Battalion soldiers served in the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force in German New Guinea in 1914.[136]

- ↑ Inherited by the 2nd Battalion from the 2/2nd Battalion (2nd AIF) in 1961.[4][136]

- Citations

- ↑ Kuring 2004, p. 47.

- ↑ Grey 2008, pp. 85 & 88.

- ↑ Bean 1941a, p. 41.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Harris, Ted. "Off Orbat RNSWR Battalions". Digger History. Archived from the original on 20 August 2008. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ Kuring 2004, p. 90.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "2nd Battalion". First World War, 1914–1918 units. Australian War Memorial. Archived from the original on 10 September 2011. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ Taylor & Cusack 1942, p. 29.

- 1 2 Ryan 2003, p. 11.

- ↑ Bean 1941a, p. 52.

- ↑ Grey 2008, p. 88.

- ↑ Grey 2008, p. 91.

- ↑ Mallett, Ross. "Part B: Branches – Infantry Battalions". First AIF Order of Battle 1914–1918. Australian Defence Force Academy. Archived from the original on 27 September 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ Grey 2008, p. 92.

- ↑ Taylor & Cusack 1942, p. 17.

- ↑ Grey 2008, p. 93.

- 1 2 Bean 1941a, p. 164.

- ↑ Grey 2008, pp. 93–94.

- ↑ Bean 1941a, p. 281.

- ↑ Bean 1941a, pp. 294, 296 & 299.

- ↑ Bean 1941a, pp. 309–316.

- 1 2 3 McIntyre 1979, pp. 392–393.

- ↑ Grey 2008, p. 94.

- ↑ Bean 1941b, p. 44.

- ↑ Bean 1941b, p. 137.

- ↑ Bean 1941b, p. 142.

- ↑ Bean 1941b, pp. 143–144.

- ↑ Bean 1941b, p. 144.

- ↑ Bean 1941b, pp. 167–168.

- ↑ Bean 1941b, p. 251.

- ↑ Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 107.

- ↑ Bean 1941b, p. 498.

- ↑ Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 108.

- ↑ Bean 1941b, p. 566.

- ↑ Bean 1941a, p. 296.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sweeting 1990, pp. 73–74.

- 1 2 Baldwin 1962, p. 61.

- ↑ Broadbent 2005, p. 251.

- ↑ Broadbent 2005, pp. 251–255.

- ↑ Broadbent 2005, p. 258.

- ↑ Baldwin 1962, p. 62.

- ↑ Cameron 2011, p. 316.

- ↑ Bean 1941b, p. 877.

- ↑ Grey 2008, p. 98.

- ↑ Grey 2008, pp. 99–100.

- ↑ Bean 1941c, p. 42.

- ↑ Bean 1941c, pp. 48–49.

- ↑ Taylor & Cusack 1942, p. 18.

- ↑ Grey 2008, p. 100.

- ↑ Bean 1941c, p. 69.

- ↑ Bean 1941c, p. 77.

- ↑ Grey 2008, p. 101.

- ↑ Bean 1941c, p. 189.

- ↑ Bean 1941c, p. 194.

- ↑ Bean 1941c, p. 471.

- ↑ Bean 1941c, pp. 260–283.

- ↑ Bean 1941c, p. 477.

- ↑ Bean 1941c, p. 478.

- ↑ Bean 1941c, p. 494.

- ↑ Bean 1941c, p. 495.

- ↑ Bean 1941c, pp. 496–497.

- ↑ Bean 1941c, p. 502.

- ↑ Bean 1941c, pp. 516–517.

- ↑ Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 117.

- ↑ Bean 1941c, p. 586.

- ↑ Bean 1941c, p. 593.

- ↑ Taylor & Cusack 1942, p. 19.

- ↑ Bean 1941c, p. 771.

- ↑ Bean 1941c, pp. 790–791.

- ↑ Bean 1941c, p. 877.

- 1 2 Bean 1941c, p. 878.

- ↑ Bean 1941c, p. 879.

- ↑ Bean 1941c, p. 884.

- ↑ Bean 1941c, pp. 884–885.

- ↑ Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 120

- ↑ Bean 1941c, p. 905.

- ↑ Bean 1941c, p. 950.

- 1 2 Horner 1998, pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Ryan 2003, p. 12.

- ↑ Baldwin 1962, pp. 98–100.

- 1 2 Baldwin 1962, p. 99.

- ↑ Taylor & Cusack 1942, p. 20.

- 1 2 3 4 Haken 1986, pp. 514–515.

- ↑ Bean 1941d, pp. 238–239.

- ↑ Bean 1941d, p. 239.

- ↑ Bean 1941d, p. 242.

- ↑ Bean 1941d, pp. 243–244.

- ↑ Bean 1941d, p. 244.

- ↑ Higgins 1983, pp. 571–572.

- ↑ Bean 1941d, pp. 245–246.

- ↑ Bean 1941d, p. 247.

- ↑ Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 126.

- ↑ Bean 1941d, p. 430.

- ↑ Bean 1941d, pp. 475–476.

- ↑ Bean 1941d, p. 488.

- ↑ Bean 1941d, pp. 492–521

- ↑ Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 127.

- 1 2 Bean 1941d, p. 750.

- 1 2 Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 131.

- ↑ Bean 1941d, p. 797.

- ↑ Bean 1941d, p. 788.

- ↑ Bean 1941d, p. 789.

- ↑ Bean 1941d, pp. 834 & 837.

- ↑ Bean 1941d, p. 841

- ↑ Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 132.

- ↑ Bean 1941d, p. 876.

- ↑ Bean 1941d, pp. 843–844.

- ↑ Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 134.

- ↑ Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 138.

- ↑ Taylor & Cusack 1942, p. 22.

- 1 2 Baldwin 1962, p. 126.

- 1 2 Baldwin 1962, p. 141.

- ↑ Bean 1941e, p. 112.

- 1 2 Grey 2008, p. 108.

- ↑ Bean 1941e, p. 420.

- ↑ Bean 1941e, pp. 443–444.

- ↑ Bean 1941e, p. 448.

- ↑ Bean 1941e, p. 484.

- ↑ Bean 1942, p. 49.

- ↑ Bean 1942, pp. 56–57.

- ↑ Bean 1942, pp. 384.

- ↑ Bean 1942, pp. 391, 410 & 420.

- ↑ Bean 1942, p. 601.

- ↑ Bean 1942, p. 617.

- ↑ Bean 1942, pp. 650 & 669.

- ↑ Bean 1942, p. 678.

- ↑ Bean 1942, p. 684.

- 1 2 Bean 1942, p. 887.

- ↑ Bean 1942, p. 888.

- ↑ Bean 1942, p. 931.

- ↑ Taylor & Cusack 1942, p. 333.

- ↑ Bean 1942, p. 935.

- ↑ Grey 2008, p. 109.

- 1 2 Grey 2008, p. 125.

- ↑ Palazzo 2001, p. 102.

- ↑ Harris, Ted. "Australian Infantry Unit Colour Patches 1921–1949". Digger History. Archived from the original on 6 March 2011. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Festberg 1972, p. 59.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "2nd Infantry Battalion". Regiments.org (archived). Archived from the original on 18 November 2007. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- 1 2 Stanley, Peter. "Broken Lineage: The Australian Army's Heritage of Discontinuity" (PDF). A Century of Service. Army History Unit. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 March 2011. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Harris, Ted. "Lineage of the Royal New South Wales Regiment". Digger History. Archived from the original on 13 October 2008. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Festberg 1972, p. 60.

- ↑ Grey 2008, p. 138.

- ↑ Palazzo 2001, p. 110.

- ↑ Keogh 1965, p. 44.

- ↑ "2 Infantry Battalion: Appointments". Orders of Battle.com. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- 1 2 "2 Infantry Battalion: History". Orders of Battle.com. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- ↑ Keogh 1965, p. 49.

- ↑ "2 Infantry Battalion: Superiors". Orders of Battle.com. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- ↑ Grey 2008, pp. 200–201.

- ↑ "A Brief History of the 2nd Division" (PDF). Army History Unit. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2009. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- 1 2 Grey 2008, p. 228.

- 1 2 Palazzo 2001, p. 259.

- 1 2 "2/2nd Battalion". Second World War, 1939–1945 units. Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- 1 2 2/17 Battalion History Committee 1998, pp. 332–333

- ↑ Shaw 2010, p. 11

- ↑ Kuring 2004, p. 436.

- ↑ Bean 1942, p. 193.

References

- 2/17 Battalion History Committee (1998). What We Have We Hold: A History of the 2/17 Australian Infantry Battalion, 1940–1945. Loftus, New South Wales: Australian Military History Publications. ISBN 1-876439-36-X.

- Baldwin, Hanson (1962). World War I: An Outline History. London: Hutchinson. OCLC 988365.

- Bean, Charles (1941a). The Story of ANZAC from the Outbreak of War to the End of the First Phase of the Gallipoli Campaign, May 4, 1915. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918 I (11th ed.). Sydney, New South Wales: Angus and Robertson. OCLC 37052344.

- Bean, Charles (1941b). The Story of ANZAC from May 4, 1915, to the Evacuation of the Gallipoli Peninsula. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918 II (11th ed.). Sydney, New South Wales: Angus and Robertson. OCLC 220898941.

- Bean, Charles (1941c). The Australian Imperial Force in France, 1916. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918 III (12th ed.). Sydney, New South Wales: Angus and Robertson. OCLC 220623454.

- Bean, Charles (1941d). The Australian Imperial Force in France, 1917. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918 IV (11th ed.). Sydney, New South Wales: Angus and Robertson. OCLC 220898229.

- Bean, Charles (1941e). The Australian Imperial Force in France during the Main German Offensive, 1918. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918 V (8th ed.). Sydney, New South Wales: Angus and Robertson. OCLC 220898057.

- Bean, Charles (1942). The Australian Imperial Force in France during the Allied Offensive, 1918. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918 VI (1st ed.). Sydney, New South Wales: Angus and Robertson. OCLC 41008291.

- Broadbent, Harvey (2005). Gallipoli: The Fatal Shore. Camberwell, Victoria: Penguin Group Australia. ISBN 0-670-04085-1.

- Cameron, David (2011). Gallipoli: The Final Battles and Evacuation of Anzac. Newport, New South Wales: Big Sky Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9808140-9-5.

- Coulthard-Clark, Chris (1998). Where Australians Fought: The Encyclopaedia of Australia's Battles. St Leonards, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86448-611-2.

- Festberg, Alfred (1972). The Lineage of the Australian Army. Melbourne, Victoria: Allara Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85887-024-6.

- Grey, Jeffrey (2008). A Military History of Australia (3rd ed.). Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-69791-0.

- Haken, J.K. (1986). "Milligan, Stanley Lyndall (1887–1968)". Australian Dictionary of Biography 10. Melbourne, Victoria: Melbourne University Press. pp. 514–515.

- Higgins, Matthew (1983). "Kenny, Thomas James Bede (1896–1953)". Australian Dictionary of Biography 9. Melbourne, Victoria: Melbourne University Press. pp. 571–572.

- Horner, David (1998). Blamey: The Commander-in-Chief. St Leonards, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86448-734-8.

- Keogh, Eustace (1965). The South West Pacific 1941–45. Melbourne, Victoria: Grayflower Productions. OCLC 7185705.

- Kuring, Ian (2004). Redcoats to Cams: A History of Australian Infantry 1788–2001. Loftus, New South Wales: Australian Military History Publications. ISBN 1-876439-99-8.

- McIntyre, Darryl (1979). "Braund, George Frederick (1866–1915)". Australian Dictionary of Biography 7. Melbourne, Victoria: Melbourne University Press. pp. 392–393.

- Palazzo, Albert (2001). The Australian Army. A History of its Organisation 1901–2001. South Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-551507-2.

- Ryan, Alan (2003). Putting Your Young Men in the Mud: Change, Continuity and the Australian Infantry Battalion. Land Warfare Studies Centre Working Papers. Working Paper No. 124. Duntroon, Australian Capital Territory: Land Warfare Studies Centre. ISBN 0-642-29595-6.

- Shaw, Peter (2010). "The Evolution of the Infantry State Regiment System in the Army Reserve". Sabretache (Garran, Australian Capital Territory: Military Historical Society of Australia) LI (4 (December)): 5–12. ISSN 0048-8933.

- Sweeting, A.J. (1990). "Stevens, Arthur Borlase (1880–1965)". Australian Dictionary of Biography 12. Melbourne, Victoria: Melbourne University Press. pp. 73–74.

- Taylor, Frederick; Cusack, Timothy (1942). Nulli Secundus: A History of the 2nd Battalion, AIF, 1914–1919. Sydney, New South Wales: New Century Press. OCLC 35134503.