Instrumental variable

In statistics, econometrics, epidemiology and related disciplines, the method of instrumental variables (IV) is used to estimate causal relationships when controlled experiments are not feasible or when a treatment is not successfully delivered to every unit in a randomized experiment.[1]

Instrumental variable methods allow consistent estimation when the explanatory variables (covariates) are correlated with the error terms of a regression relationship. Such correlation may occur when the dependent variable causes at least one of the covariates ("reverse" causation), when there are relevant explanatory variables which are omitted from the model, or when the covariates are subject to measurement error. In this situation, ordinary linear regression generally produces biased and inconsistent estimates.[2] However, if an instrument is available, consistent estimates may still be obtained. An instrument is a variable that does not itself belong in the explanatory equation and is correlated with the endogenous explanatory variables, conditional on the other covariates. In linear models, there are two main requirements for using an IV:

- The instrument must be correlated with the endogenous explanatory variables, conditional on the other covariates.

- The instrument cannot be correlated with the error term in the explanatory equation (conditional on the other covariates), that is, the instrument cannot suffer from the same problem as the original predicting variable.

Definitions

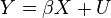

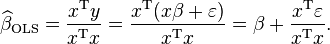

The theory of instrumental variables was first derived by Philip G. Wright, possibly in co-authorship with his son Sewall Wright, in his 1928 book The Tariff on Animal and Vegetable Oils.[3][4] Traditionally,[5] an instrumental variable is defined as a variable Z that is correlated with the independent variable X and uncorrelated with the "error term" U in the equation

However, this definition suffers from ambiguities in concepts such as "error term" and "independent variable," and has led to confusion as to the meaning of the equation itself, which was wrongly labeled "regression."[6]

General definitions of instrumental variables, using counterfactual and graphical formalism, were given by Pearl (2000; p. 248).[7] The graphical definition requires that Z satisfy the following conditions:

where  stands for d-separation [8] and

stands for d-separation [8] and  stands for the graph in which all arrows entering X are cut off.

stands for the graph in which all arrows entering X are cut off.

The counterfactual definition requires that Z satisfies

where Yx stands for the value that Y would attain had X been x and  stands for independence.

stands for independence.

If there are additional covariates W then the above definitions are modified so that Z qualifies as an instrument if the given criteria hold conditional on W.

The essence of Pearl's definition is:

- The equations of interest are "structural," not "regression."

- The error term U stands for all exogenous factors that affect Y when X is held constant.

- The instrument Z should be independent of U.

- The instrument Z should not affect Y when X is held constant (exclusion restriction).

- The instrument Z should not be independent of X.

These conditions do not rely on specific functional form of the equations and are applicable therefore to nonlinear equations, where U can be non-additive (see Non-parametric analysis). They are also applicable to a system of multiple equations, in which X (and other factors) affect Y through several intermediate variables. Note that an instrumental variable need not be a cause of X; a proxy of such cause may also be used, if it satisfies conditions 1-5.[7] Note also that the exclusion restriction (condition 4) is redundant; it follows from conditions 2 and 3.

Example

Informally, in attempting to estimate the causal effect of some variable x on another y, an instrument is a third variable z which affects y only through its effect on x. For example, suppose a researcher wishes to estimate the causal effect of smoking on general health.[9] Correlation between health and smoking does not imply that smoking causes poor health because other variables may affect both health and smoking, or because health may affect smoking. It is at best difficult and expensive to conduct controlled experiments on smoking status in the general population. The researcher may attempt to estimate the causal effect of smoking on health from observational data by using the tax rate for tobacco products as an instrument for smoking. The tax rate for tobacco products is a reasonable choice for an instrument because the researcher assumes that it can only be correlated with health through its effect on smoking. If the researcher then finds tobacco taxes and state of health to be correlated, this may be viewed as evidence that smoking causes changes in health.

Applications

IV methods are commonly used to estimate causal effects in contexts in which controlled experiments are not available. Credibility of the estimates hinges on the selection of suitable instruments. Good instruments are often created by policy changes. For example, the cancellation of a federal student-aid scholarship program may reveal the effects of aid on some students' outcomes. Other natural and quasi-natural experiments of various types are commonly exploited, for example, Miguel, Satyanath, and Sergenti (2004) use weather shocks to identify the effect of changes in economic growth (i.e., declines) on civil conflict.[10] Angrist and Krueger (2001) present a survey of the history and uses of instrumental variable techniques.[11]

Selecting suitable instruments

Since U is unobserved, the requirement that Z be independent of U cannot be inferred from data and must instead be determined from the model structure, i.e., the data-generating process. Causal graphs are a representation of this structure, and the graphical definition given above can be used to quickly determine whether a variable Z qualifies as an instrumental variable given a set of covariates W. To see how, consider the following example.

_2.png)

, which is used to determine whether Proximity is an instrumental variable.

, which is used to determine whether Proximity is an instrumental variable.

Suppose that we wish to estimate the effect of a university tutoring program on GPA. The relationship between attending the tutoring program and GPA may be confounded by a number of factors. Students that attend the tutoring program may care more about their grades or may be struggling with their work. This confounding is depicted in the Figures 1-3 on the right through the bidirected arc between Tutoring Program and GPA. If that students are assigned to dormitories at random, the proximity of the student's dorm to the tutoring program is a natural candidate for being an instrumental variable.

However, what if the tutoring program is located in the college library? In that case, Proximity may also cause students to spend more time at the library, which in turn improves their GPA (see Figure 1). Using the causal graph depicted in the Figure 2, we see that Proximity does not qualify as an instrumental variable because it is connected to GPA through the path Proximity  Library Hours

Library Hours  GPA in

GPA in  . However, if we control for Library Hours by adding it as a covariate then Proximity becomes an instrumental variable, since Proximity is separated from GPA given Library Hours in

. However, if we control for Library Hours by adding it as a covariate then Proximity becomes an instrumental variable, since Proximity is separated from GPA given Library Hours in  .

.

Now, suppose that we notice that a student's "natural ability" affects his or her number of hours in the library as well as his or her GPA, as in Figure 3. Using the causal graph, we see that Library Hours is a collider and conditioning on it opens the path Proximity  Library Hours

Library Hours  GPA. As a result, Proximity cannot be used as an instrumental variable.

GPA. As a result, Proximity cannot be used as an instrumental variable.

Finally, suppose that Library Hours does not actually affect GPA because students who do not study in the library simply study elsewhere, as in Figure 4. In this case, controlling for Library Hours still opens a spurious path from Proximity to GPA. However, if we do not control for Library Hours and remove it as a covariate then Proximity can again be used an instrumental variable.

Estimation

Suppose the data are generated by a process of the form

where

- i indexes observations,

-

is the dependent variable,

is the dependent variable, -

is an independent variable,

is an independent variable, -

is an unobserved error term representing all causes of

is an unobserved error term representing all causes of  other than

other than  , and

, and -

is an unobserved scalar parameter.

is an unobserved scalar parameter.

The parameter  is the causal effect on

is the causal effect on  of a one unit change in

of a one unit change in  , holding all other causes of

, holding all other causes of  constant. The econometric goal is to estimate

constant. The econometric goal is to estimate  . For simplicity's sake assume the draws of

. For simplicity's sake assume the draws of  are uncorrelated and that they are drawn from distributions with the same variance, that is, that the errors are serially uncorrelated and homoskedastic.

are uncorrelated and that they are drawn from distributions with the same variance, that is, that the errors are serially uncorrelated and homoskedastic.

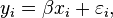

Suppose also that a regression model of nominally the same form is proposed. Given a random sample of T observations from this process, the ordinary least squares estimator is

where x, y and  denote column vectors of length T. When x and

denote column vectors of length T. When x and  are uncorrelated, under certain regularity conditions the second term has an expected value conditional on x of zero and converges to zero in the limit, so the estimator is unbiased and consistent. When x and the other unmeasured, causal variables collapsed into the

are uncorrelated, under certain regularity conditions the second term has an expected value conditional on x of zero and converges to zero in the limit, so the estimator is unbiased and consistent. When x and the other unmeasured, causal variables collapsed into the  term are correlated, however, the OLS estimator is generally biased and inconsistent for β. In this case, it is valid to use the estimates to predict values of y given values of x, but the estimate does not recover the causal effect of x on y.

term are correlated, however, the OLS estimator is generally biased and inconsistent for β. In this case, it is valid to use the estimates to predict values of y given values of x, but the estimate does not recover the causal effect of x on y.

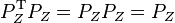

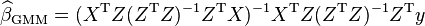

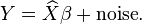

An instrumental variable z is one that is correlated with the independent variable but not with the error term. Using the method of moments, take expectations conditional on z to find

The second term on the right-hand side is zero by assumption. Solve for  and write the resulting expression in terms of sample moments,

and write the resulting expression in terms of sample moments,

When z and  are uncorrelated, the final term, under certain regularity conditions, approaches zero in the limit, providing a consistent estimator. Put another way, the causal effect of x on y can be consistently estimated from these data even though x is not randomly assigned through experimental methods.

are uncorrelated, the final term, under certain regularity conditions, approaches zero in the limit, providing a consistent estimator. Put another way, the causal effect of x on y can be consistently estimated from these data even though x is not randomly assigned through experimental methods.

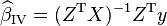

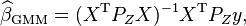

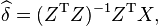

The approach generalizes to a model with multiple explanatory variables. Suppose X is the T × K matrix of explanatory variables resulting from T observations on K variables. Let Z be a T × K matrix of instruments. Then it can be shown that the estimator

is consistent under a multivariate generalization of the conditions discussed above. If there are more instruments than there are covariates in the equation of interest so that Z is a T × M matrix with M > K, the generalized method of moments (GMM) can be used and the resulting IV estimator is

where  .

.

Note that the second expression collapses to the first when the number of instruments is equal to the number of covariates in the equation of interest (just-identified case).

Developing the  expression:

expression:

In the just-identified case, we have as many instruments as covariates, so that the dimension of X is the same of Z. Hence,  and

and  are all squared matrices of the same dimension. We can expand the inverse, using the fact that, for any invertible n-by-n matrices A and B, (AB)−1 = B−1A−1 (see Invertible matrix#Properties):

are all squared matrices of the same dimension. We can expand the inverse, using the fact that, for any invertible n-by-n matrices A and B, (AB)−1 = B−1A−1 (see Invertible matrix#Properties):

Reference: see Davidson and Mackinnnon (1993)[12]:218

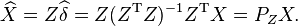

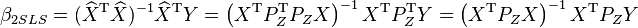

Interpretation as two-stage least squares

One computational method which can be used to calculate IV estimates is two-stage least-squares (2SLS or TSLS). In the first stage, each explanatory variable that is an endogenous covariate in the equation of interest is regressed on all of the exogenous variables in the model, including both exogenous covariates in the equation of interest and the excluded instruments. The predicted values from these regressions are obtained.

Stage 1: Regress each column of X on Z, ( )

)

and save the predicted values:

In the second stage, the regression of interest is estimated as usual, except that in this stage each endogenous covariate is replaced with the predicted values from the first stage.

Stage 2: Regress Y on the predicted values from the first stage:

Which gives:

Note that the usual OLS estimator is:  .

Replacing

.

Replacing  and noting that

and noting that  is a symmetric and idempotent matrix, so that

is a symmetric and idempotent matrix, so that

The resulting estimator of  is numerically identical to the expression displayed above. A small correction must be made to the sum-of-squared residuals in the second-stage fitted model in order that the covariance matrix of

is numerically identical to the expression displayed above. A small correction must be made to the sum-of-squared residuals in the second-stage fitted model in order that the covariance matrix of  is calculated correctly.

is calculated correctly.

Identification

In the instrumental variable regression, if we have multiple endogenous regressors  and multiple instruments

and multiple instruments  the coefficients on the endogenous regressors

the coefficients on the endogenous regressors  are said to be:

are said to be:

Exactly identified if m = k.

Overidentified if m > k.

Underidentified if m < k.

The parameters are underidentified (equivalently, not identified) if there are fewer instruments than there are covariates or, equivalently, if there are fewer excluded instruments than there are endogenous covariates in the equation of interest.

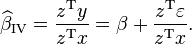

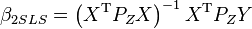

Non-parametric analysis

When the form of the structural equations is unknown, an instrumental variable  can still be defined through the equations:

can still be defined through the equations:

where  and

and  are two arbitrary functions and

are two arbitrary functions and  is independent of

is independent of  . Unlike linear models, however, measurements of

. Unlike linear models, however, measurements of  and

and  do not allow for the identification of the average causal effect of

do not allow for the identification of the average causal effect of  on

on  , denoted ACE

, denoted ACE

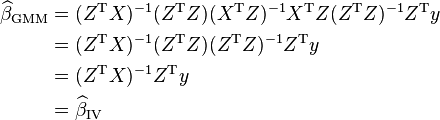

Balke and Pearl [1997] derived tight bounds on ACE and showed that these can provide valuable information on the sign and size of ACE.[13]

In linear analysis, there is no test to falsify the assumption the  is instrumental relative to the pair

is instrumental relative to the pair  . This is not the case when

. This is not the case when  is discrete. Pearl (2000) has shown that, for all

is discrete. Pearl (2000) has shown that, for all  and

and  , the following constraint, called "Instrumental Inequality" must hold whenever

, the following constraint, called "Instrumental Inequality" must hold whenever  satisfies the two equations above:[7]

satisfies the two equations above:[7]

On the interpretation of IV estimates

The exposition above assumes that the causal effect of interest does not vary across observations, that is, that  is a constant. Generally, different subjects will respond in different ways to changes in the "treatment" x. When this possibility is recognized, the average effect in the population of a change in x on y may differ from the effect in a given subpopulation. For example, the average effect of a job training program may substantially differ across the group of people who actually receive the training and the group which chooses not to receive training. For these reasons, IV methods invoke implicit assumptions on behavioral response, or more generally assumptions over the correlation between the response to treatment and propensity to receive treatment.[14]

is a constant. Generally, different subjects will respond in different ways to changes in the "treatment" x. When this possibility is recognized, the average effect in the population of a change in x on y may differ from the effect in a given subpopulation. For example, the average effect of a job training program may substantially differ across the group of people who actually receive the training and the group which chooses not to receive training. For these reasons, IV methods invoke implicit assumptions on behavioral response, or more generally assumptions over the correlation between the response to treatment and propensity to receive treatment.[14]

The standard IV estimator can recover local average treatment effects (LATE) rather than average treatment effects (ATE).[1] Imbens and Angrist (1994) demonstrate that the linear IV estimate can be interpreted under weak conditions as a weighted average of local average treatment effects, where the weights depend on the elasticity of the endogenous regressor to changes in the instrumental variables. Roughly, that means that the effect of a variable is only revealed for the subpopulations affected by the observed changes in the instruments, and that subpopulations which respond most to changes in the instruments will have the largest effects on the magnitude of the IV estimate.

For example, if a researcher uses presence of a land-grant college as an instrument for college education in an earnings regression, she identifies the effect of college on earnings in the subpopulation which would obtain a college degree if a college is present but which would not obtain a degree if a college is not present. This empirical approach does not, without further assumptions, tell the researcher anything about the effect of college among people who would either always or never get a college degree regardless of whether a local college exists.

Potential problems

Instrumental variables estimates are generally inconsistent if the instruments are correlated with the error term in the equation of interest. Another problem is caused by the selection of "weak" instruments, instruments that are poor predictors of the endogenous question predictor in the first-stage equation.[15] In this case, the prediction of the question predictor by the instrument will be poor and the predicted values will have very little variation. Consequently, they are unlikely to have much success in predicting the ultimate outcome when they are used to replace the question predictor in the second-stage equation.

In the context of the smoking and health example discussed above, tobacco taxes are weak instruments for smoking if smoking status is largely unresponsive to changes in taxes. If higher taxes do not induce people to quit smoking (or not start smoking), then variation in tax rates tells us nothing about the effect of smoking on health. If taxes affect health through channels other than through their effect on smoking, then the instruments are invalid and the instrumental variables approach may yield misleading results. For example, places and times with relatively health-conscious populations may both implement high tobacco taxes and exhibit better health even holding smoking rates constant, so we would observe a correlation between health and tobacco taxes even if it were the case that smoking has no effect on health. In this case, we would be mistaken to infer a causal effect of smoking on health from the observed correlation between tobacco taxes and health.

Sampling properties and hypothesis testing

When the covariates are exogenous, the small-sample properties of the OLS estimator can be derived in a straightforward manner by calculating moments of the estimator conditional on X. When some of the covariates are endogenous so that instrumental variables estimation is implemented, simple expressions for the moments of the estimator cannot be so obtained. Generally, instrumental variables estimators only have desirable asymptotic, not finite sample, properties, and inference is based on asymptotic approximations to the sampling distribution of the estimator. Even when the instruments are uncorrelated with the error in the equation of interest and when the instruments are not weak, the finite sample properties of the instrumental variables estimator may be poor. For example, exactly identified models produce finite sample estimators with no moments, so the estimator can be said to be neither biased nor unbiased, the nominal size of test statistics may be substantially distorted, and the estimates may commonly be far away from the true value of the parameter.[16]

Testing instrument strength and overidentifying restrictions

The strength of the instruments can be directly assessed because both the endogenous covariates and the instruments are observable.[17] A common rule of thumb for models with one endogenous regressor is: the F-statistic against the null that the excluded instruments are irrelevant in the first-stage regression should be larger than 10.

The assumption that the instruments are not correlated with the error term in the equation of interest is not testable in exactly identified models. If the model is overidentified, there is information available which may be used to test this assumption. The most common test of these overidentifying restrictions, called the Sargan test, is based on the observation that the residuals should be uncorrelated with the set of exogenous variables if the instruments are truly exogenous. The Sargan test statistic can be calculated as  (the number of observations multiplied by the coefficient of determination) from the OLS regression of the residuals onto the set of exogenous variables. This statistic will be asymptotically chi-squared with m − k degrees of freedom under the null that the error term is uncorrelated with the instruments.

(the number of observations multiplied by the coefficient of determination) from the OLS regression of the residuals onto the set of exogenous variables. This statistic will be asymptotically chi-squared with m − k degrees of freedom under the null that the error term is uncorrelated with the instruments.

References

- 1 2 Imbens, G.; Angrist, J. (1994). "Identification and estimation of local average treatment effects". Econometrica 62 (2): 467–476. JSTOR 2951620.

- ↑ Bullock, J. G.; Green, D. P.; Ha, S. E. (2010). "Yes, But What’s the Mechanism? (Don’t Expect an Easy Answer)". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 98 (4): 550–558. doi:10.1037/a0018933.

- ↑ "The Fall of OLS in Structural Estimation". doi:10.2307/2663184 (inactive 2015-03-23). JSTOR 2663184.

- ↑ Stock, James H.; Trebbi, Francesco (2003). "Retrospectives: Who Invented Instrumental Variable Regression?". Journal of Economic Perspectives 17 (3): 177–194. doi:10.1257/089533003769204416.

- ↑ Bowden, R.J.; Turkington, D.A. (1984). Instrumental Variables. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Angrist, J.D.; Imbens, G.W.; Rubin, D.B. (1996). "Identification and causal effects using instrumental variables". Journal of the American Statistical Association 91 (434): 444 455. doi:10.1080/01621459.1996.10476902.

- 1 2 3 Pearl, J. (2000). Causality: Models, Reasoning, and Inference. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-89560-X.

- ↑ Bayesian network

- ↑ Leigh, J. P.; Schembri, M. (2004). "Instrumental Variables Technique: Cigarette Price Provided Better Estimate of Effects of Smoking on SF-12". Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 57 (3): 284–293. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.08.006.

- ↑ Miguel, E.; Satyanath, S.; Sergenti, E. (2004). "Economic Shocks and Civil Conflict: An Instrumental Variable Approach". Journal of Political Economy 112 (4): 725–753. doi:10.1086/421174.

- ↑ Angrist, J.; Krueger, A. (2001). "Instrumental Variables and the Search for Identification: From Supply and Demand to Natural Experiments". Journal of Economic Perspectives 15 (4): 69–85. doi:10.1257/jep.15.4.69.

- ↑ Davidson, Russell; Mackinnon, James (1993). Estimation and Inference in Econometrics. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506011-3.

- ↑ Balke, A.; Pearl, J. (1997). "Bounds on treatment effects from studies with imperfect compliance". Journal of the American Statistical Association 92 (439): 1172–1176. doi:10.1080/01621459.1997.10474074.

- ↑ Heckman, J. (1997). "Instrumental variables: A study of implicit behavioral assumptions used in making program evaluations". Journal of Human Resources 32 (3): 441–462. JSTOR 146178.

- ↑ Bound, J.; Jaeger, D. A.; Baker, R. M. (1995). "Problems with Instrumental Variables Estimation when the Correlation between the Instruments and the Endogenous Explanatory Variable is Weak". Journal of the American Statistical Association 90 (430): 443. doi:10.1080/01621459.1995.10476536.

- ↑ Nelson, C. R.; Startz, R. (1990). "Some Further Results on the Exact Small Sample Properties of the Instrumental Variable Estimator". Econometrica 58 (4): 967–976. JSTOR 2938359.

- ↑ Stock, J.; Wright, J.; Yogo, M. (2002). "A Survey of Weak Instruments and Weak Identification in Generalized Method of Moments". Journal of the American Statistical Association 20 (4): 518–529. doi:10.1198/073500102288618658.

Further reading

- Greene, William H. (2008). Econometric Analysis (Sixth ed.). Upper Saddle River: Pearson Prentice-Hall. pp. 314–353. ISBN 978-0-13-600383-0.

- Gujarati, Damodar N.; Porter, Dawn C. (2009). Basic Econometrics (Fifth ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Irwin. pp. 711–736. ISBN 978-0-07-337577-9.

- Wooldridge, Jeffrey M. (2013). Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach (Fifth international ed.). Mason, OH: South-Western. pp. 490–528. ISBN 978-1-111-53439-4.

External links

- Layman's explanation of instrumental variables.

- Chapter from Daniel McFadden's textbook

- Econometrics lecture (topic: instrumental variable) on YouTube by Mark Thoma.

- Econmetrics lecture (topic: two-stages least square) on YouTube by Mark Thoma

![E [ y \mid z ] = \beta E [ x \mid z ] + E [ \varepsilon \mid z ]. \,](../I/m/bf4bd8db0424f1474b0c83305efece95.png)

![\text{ACE} = \Pr(y\mid \text{do}(x)) = \operatorname{E}_u[f(x,u)].](../I/m/8d699affa4fae1ac4fabbd411d310f5c.png)

![\max_x \sum_y [\max_z \Pr(y,x\mid z)]\leq 1.](../I/m/cfc14161a276b106e7138c79a8c59e51.png)