2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami

An aerial view of the Sendai region with black smoke coming from the Nippon Oil refinery | |

Tokyo Sendai | |

| Date | 11 March 2011 |

|---|---|

| Origin time | 14:46:24 JST (UTC+09:00) |

| Duration | 6 minutes[1] |

| Magnitude | 9.0 Mw[2][3] |

| Depth | 30 km (19 mi) |

| Epicenter | 38°19′19″N 142°22′08″E / 38.322°N 142.369°ECoordinates: 38°19′19″N 142°22′08″E / 38.322°N 142.369°E |

| Type | Megathrust |

| Areas affected |

Japan (shaking, tsunami) Pacific Rim (tsunami) |

| Total damage | Tsunami wave, flooding, landslides, fires, building and infrastructure damage, nuclear incidents including radiation releases |

| Max. intensity | IX (Violent) |

| Peak acceleration | 2.99 g |

| Tsunami |

Up to 40.5 m (133 ft) in Miyako, Iwate, Tōhoku |

| Landslides | Yes |

| Foreshocks | List of foreshocks and aftershocks of the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake |

| Aftershocks | 11,450 (as of 3 March 2015)[4] |

| Casualties |

15,893 deaths,[5] 6,152 injured,[6] 2,572 people missing[7] |

The 2011 earthquake off the Pacific coast of Tōhoku (東北地方太平洋沖地震 Tōhoku-chihō Taiheiyō Oki Jishin) was a magnitude 9.0 (Mw) undersea megathrust earthquake off the coast of Japan that occurred at 14:46 JST (05:46 UTC) on Friday 11 March 2011,[2][3][8] with the epicentre approximately 70 kilometres (43 mi) east of the Oshika Peninsula of Tōhoku and the hypocenter at an underwater depth of approximately 30 km (19 mi).[2][9] The earthquake is also often referred to in Japan as the Great East Japan earthquake (東日本大震災 Higashi nihon daishinsai)[10][11][12][fn 1] and also known as the 2011 Tohoku earthquake,[26] and the 3.11 earthquake. It was the most powerful earthquake ever recorded to have hit Japan, and the fourth most powerful earthquake in the world since modern record-keeping began in 1900.[8][27][28] The earthquake triggered powerful tsunami waves that reached heights of up to 40.5 metres (133 ft) in Miyako in Tōhoku's Iwate Prefecture,[29][30] and which, in the Sendai area, travelled up to 10 km (6 mi) inland.[31] The earthquake moved Honshu (the main island of Japan) 2.4 m (8 ft) east, shifted the Earth on its axis by estimates of between 10 cm (4 in) and 25 cm (10 in),[32][33][34] and generated sound waves detected by the low-orbiting GOCE satellite.[35]

On 10 March 2015, a Japanese National Police Agency report confirmed 15,893 deaths,[36] 6,152 injured,[37] and 2,572 people missing[38] across twenty prefectures, as well as 228,863 people living away from their home in either temporary housing or due to permanent relocation.[39] A 10 February 2014 agency report listed 127,290 buildings totally collapsed, with a further 272,788 buildings 'half collapsed', and another 747,989 buildings partially damaged.[40] The earthquake and tsunami also caused extensive and severe structural damage in north-eastern Japan, including heavy damage to roads and railways as well as fires in many areas, and a dam collapse.[31][41] Japanese Prime Minister Naoto Kan said, "In the 65 years after the end of World War II, this is the toughest and the most difficult crisis for Japan."[42] Around 4.4 million households in northeastern Japan were left without electricity and 1.5 million without water.[43]

The tsunami caused nuclear accidents, primarily the level 7 meltdowns at three reactors in the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant complex, and the associated evacuation zones affecting hundreds of thousands of residents.[44][45] Many electrical generators were taken down, and at least three nuclear reactors suffered explosions due to hydrogen gas that had built up within their outer containment buildings after cooling system failure resulting from the loss of electrical power. Residents within a 20 km (12 mi) radius of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant and a 10 km (6.2 mi) radius of the Fukushima Daini Nuclear Power Plant were evacuated.

Early estimates placed insured losses from the earthquake alone at US$14.5 to $34.6 billion.[46] The Bank of Japan offered ¥15 trillion (US$183 billion) to the banking system on 14 March in an effort to normalize market conditions.[47] The World Bank's estimated economic cost was US$235 billion, making it the costliest natural disaster in world history.[48][49]

Earthquake

The 9.0 magnitude (Mw) undersea megathrust earthquake occurred on 11 March 2011 at 14:46 JST (05:46 UTC) in the north-western Pacific Ocean at a relatively shallow depth of 32 km (19.9 mi),[2][50] with its epicenter approximately 72 km (45 mi) east of the Oshika Peninsula of Tōhoku, Japan, lasting approximately six minutes.[1][2] The earthquake was initially reported as 7.9 Mw by the USGS before it was quickly upgraded to 8.8 Mw, then to 8.9 Mw,[51] and then finally to 9.0 Mw.[3][52] Sendai was the nearest major city to the earthquake, 130 km (81 mi) from the epicenter; the earthquake occurred 373 km (232 mi) from Tokyo.[2]

The main earthquake was preceded by a number of large foreshocks, with hundreds of aftershocks reported. One of the first major foreshocks was a 7.2 Mw event on 9 March, approximately 40 km (25 mi) from the epicenter of the 11 March earthquake, with another three on the same day in excess of 6.0 Mw.[2][53] Following the main earthquake on 11 March, a 7.4 Mw aftershock was reported at 15:08 JST (6:06 UTC), succeeded by a 7.9 Mw at 15:15 JST (6:16 UTC) and a 7.7 Mw at 15:26 JST (6:26 UTC).[54] Over eight hundred aftershocks of magnitude 4.5 Mw or greater have occurred since the initial quake,[55] including one on 26 October 2013 (local time) of magnitude 7.1 Mw.[56] Aftershocks follow Omori's Law, which states that the rate of aftershocks declines with the reciprocal of the time since the main quake. The aftershocks will thus taper off in time, but could continue for years.[57]

One minute before the earthquake was felt in Tokyo, the Earthquake Early Warning system, which includes more than 1,000 seismometers in Japan, sent out warnings of impending strong shaking to millions. It is believed that the early warning by the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) saved many lives.[58][59] The warning for the general public was delivered about 8 seconds after the first P wave was detected, or about 31 seconds after the earthquake occurred. However, the estimated intensities were smaller than the actual ones in some places in Kanto and Tohoku regions. This was thought to be because of smaller estimated earthquake magnitude, smaller estimated fault plane, shorter estimated fault length, not having considered the shape of the fault, etc.[60] There were also cases where large differences between estimated intensities by the Earthquake Early Warning system and the actual intensities occurred in the aftershocks and triggered earthquakes.[61]

Geology

This megathrust earthquake was a recurrence of the mechanism of the earlier 869 Sanriku earthquake, which has been estimated as having a magnitude of at least 8.4 Mw, which also created a large tsunami that inundated the Sendai plain.[62][63] Three tsunami deposits have been identified within the Holocene sequence of the plain, all formed within the last 3,000 years, suggesting an 800 to 1,100 year recurrence interval for large tsunamigenic earthquakes. In 2001 it was reckoned that there was a high likelihood of a large tsunami hitting the Sendai plain as more than 1,100 years had then elapsed.[64]

This earthquake occurred where the Pacific Plate is subducting under the plate beneath northern Honshu; which plate is a matter of debate amongst scientists.[33][65] The Pacific plate, which moves at a rate of 8 to 9 cm (3.1 to 3.5 in) per year, dips under Honshu's underlying plate building large amounts of elastic energy. This motion pushes the upper plate down until the accumulated stress causes a seismic slip-rupture event. The break caused the sea floor to rise by several metres.[65] A quake of this magnitude usually has a rupture length of at least 500 km (300 mi) and generally requires a long, relatively straight fault surface. Because the plate boundary and subduction zone in the area of the Honshu rupture is not very straight, it is unusual for the magnitude of its earthquake to exceed 8.5 Mw; the magnitude of this earthquake was a surprise to some seismologists.[66] The hypocentral region of this earthquake extended from offshore Iwate Prefecture to offshore Ibaraki Prefecture.[67] The Japanese Meteorological Agency said that the earthquake may have ruptured the fault zone from Iwate to Ibaraki with a length of 500 km (310 mi) and a width of 200 km (120 mi).[68][69] Analysis showed that this earthquake consisted of a set of three events.[70] Other major earthquakes with tsunamis struck the Sanriku Coast region in 1896 and in 1933.

The source area of this earthquake has a relatively high coupling coefficient surrounded by areas of relatively low coupling coefficients in the west, north, and south. From the averaged coupling coefficient of 0.5–0.8 in the source area and the seismic moment, it was estimated that the slip deficit of this earthquake was accumulated over a period of 260–880 years, which is consistent with the recurrence interval of such great earthquakes estimated from the tsunami deposit data. The seismic moment of this earthquake accounts for about 93% of the estimated cumulative moment from 1926 to March 2011. Hence, earthquakes with magnitudes about 7 since 1926 in this area only had released part of the accumulated energy. In the area near the trench, the coupling coefficient is high, which could act as the source of the large tsunami.[71]

Most of the foreshocks are interplate earthquakes with thrust-type focal mechanisms. Both interplate and intraplate earthquakes appeared in the aftershocks offshore Sanriku coast with considerable proportions.[72]

The strong ground motion registered at the maximum of 7 on the Japan Meteorological Agency seismic intensity scale in Kurihara, Miyagi Prefecture.[73] Three other prefectures—Fukushima, Ibaraki and Tochigi—recorded an upper 6 on the JMA scale. Seismic stations in Iwate, Gunma, Saitama and Chiba Prefecture measured a lower 6, recording an upper 5 in Tokyo.

In Russia, the main shock could be felt in Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk (MSK 4) and Kurilsk (MSK 4). The aftershock at 06:25 UTC could be felt in Yuzhno-Kurilsk (MSK 5) and Kurilsk (MSK 4).[74]

Energy

The surface energy of the seismic waves from the earthquake was calculated to be at 1.9×1017 joules,[75] which is nearly double that of the 9.1 Mw 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami that killed 230,000 people. If harnessed, the seismic energy from this earthquake would power a city the size of Los Angeles for an entire year.[57] The seismic moment (M0), which represents a physical size for the event, was calculated by the USGS at 3.9×1022 joules,[76] slightly less than the 2004 Indian Ocean quake.

Japan's National Research Institute for Earth Science and Disaster Prevention (NIED) calculated a peak ground acceleration of 2.99 g (29.33 m/s2).[77][fn 2] The largest individual recording in Japan was 2.7 g, in the Miyagi Prefecture, 75 km from the epicentre; the highest reading in the Tokyo metropolitan area was 0.16 g.[80]

Geophysical effects

Portions of northeastern Japan shifted by as much as 2.4 metres (7 ft 10 in) closer to North America,[32][33] making some sections of Japan's landmass wider than before.[33] Those areas of Japan closest to the epicenter experienced the largest shifts.[33] A 400-kilometre (250 mi) stretch of coastline dropped vertically by 0.6 metres (2 ft 0 in), allowing the tsunami to travel farther and faster onto land.[33] One early estimate suggested that the Pacific plate may have moved westward by up to 20 metres (66 ft),[81] and another early estimate put the amount of slippage at as much as 40 m (130 ft).[82] On 6 April the Japanese coast guard said that the quake shifted the seabed near the epicenter 24 metres (79 ft) and elevated the seabed off the coast of Miyagi prefecture by 3 metres (9.8 ft).[83] A report by the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology, published in Science on 2 December 2011, concluded that the seabed in the area between the epicenter and the Japan Trench moved 50 metres (160 ft) east-southeast and rose about 7 metres (23 ft) as a result of the quake. The report also stated that the quake had caused several major landslides on the seabed in the affected area.[84]

The Earth's axis shifted by estimates of between 10 cm (4 in) and 25 cm (10 in).[32][33][34] This deviation led to a number of small planetary changes, including the length of a day, the tilt of the Earth, and the Chandler wobble.[34] The speed of the Earth's rotation increased, shortening the day by 1.8 microseconds due to the redistribution of Earth's mass.[85] The axial shift was caused by the redistribution of mass on the Earth's surface, which changed the planet's moment of inertia. Because of conservation of angular momentum, such changes of inertia result in small changes to the Earth's rate of rotation.[86] These are expected changes[34] for an earthquake of this magnitude.[32][85] The earthquake also generated sound waves detected by the GOCE satellite, which thus serendipitously became the first seismograph in orbit.[35]

Soil liquefaction was evident in areas of reclaimed land around Tokyo, particularly in Urayasu,[87][88] Chiba City, Funabashi, Narashino (all in Chiba Prefecture) and in the Koto, Edogawa, Minato, Chūō, and Ōta Wards of Tokyo. Approximately 30 homes or buildings were destroyed and 1,046 other buildings were damaged to varying degrees.[89] Nearby Haneda Airport, built mostly on reclaimed land, was not damaged. Odaiba also experienced liquefaction, but damage was minimal.[90]

Shinmoedake, a volcano in Kyushu, erupted three days after the earthquake. The volcano had previously erupted in January 2011; it is not known if the later eruption was linked to the earthquake.[91] In Antarctica, the seismic waves from the earthquake were reported to have caused the Whillans Ice Stream to slip by about 0.5 metres (1 ft 8 in).[92]

The first sign international researchers had that the earthquake caused such a dramatic change in the Earth’s rotation came from the United States Geological Survey which monitors Global Positioning Satellite stations across the world. The Survey team had several GPS monitors located near the scene of the earthquake. The GPS station located nearest the epicenter moved almost 4 m (13 ft). This motivated government researchers to look into other ways the earthquake may have had large scale effects on the planet. Scientists at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory did some calculations and determined that the Earth's rotation was changed by the earthquake to the point where the days are now 1.8 microseconds shorter.[93]

Aftershocks

Japan has experienced over 1,000 aftershocks since the earthquake, with 80 registering over magnitude 6.0 Mw and several of which have been over magnitude 7.0 Mw. A magnitude 7.4 Mw at 15:08 (JST), 7.9 Mw at 15:15 and a 7.7 Mw quake at 15:26 all occurred on 11 March.[94] A month later, a major aftershock struck offshore on 7 April with a magnitude of 7.1 Mw. Its epicenter was underwater, 66 km (41 mi) off the coast of Sendai. The Japan Meteorological Agency assigned a magnitude of 7.4 MJMA, while the U.S. Geological Survey lowered it to 7.1 Mw.[95] At least four people were killed, and electricity was cut off across much of northern Japan including the loss of external power to Higashidōri Nuclear Power Plant and Rokkasho Reprocessing Plant.[96][97][98] Four days later on 11 April, another magnitude 7.1 Mw aftershock struck Fukushima, causing additional damage and killing a total of three people.[99][100] On 7 December 2012 a large aftershock of magnitude 7.3 Mw caused a minor tsunami, and again on 26 October 2013 small tsunami waves were recorded after a 7.1 Mw aftershock.[101]

As of 16 March 2012 aftershocks continued, totaling 1887 events over magnitude 4.0; a regularly updated map showing all shocks of magnitude 4.5 and above near or off the east coast of Honshu in the last seven days[102] showed over 20 events.[103] As of 6 December 2013 there have been a total of 776 aftershocks of 5.0 Mw or greater, 112 of 6.0 Mw or greater, and 8 over 7.0 Mw as reported by the Japanese Meteorological Agency.[104]

The number of aftershocks was associated with decreased health across Japan.[105]

Tsunami

An upthrust of 6 to 8 metres along a 180-km-wide seabed at 60 km offshore from the east coast of Tōhoku,[106] resulted in a major tsunami that brought destruction along the Pacific coastline of Japan's northern islands. Thousands of lives were lost when entire towns were devastated. The tsunami propagated throughout the Pacific Ocean region reaching the entire Pacific coast of North and South America from Alaska to Chile. Warnings were issued and evacuations carried out in many countries bordering the Pacific. However, while the tsunami affected many of these places, the extent was minor.[107][108][109] Chile's Pacific coast, one of the furthest from Japan at about 17,000 km (11,000 mi) distant, was struck by waves 2 m (6.6 ft) high,[110][111][112] compared with an estimated wave height of 38.9 metres (128 ft) at Omoe peninsula, Miyako city, Japan.[30]

Japan

The tsunami warning issued by the Japan Meteorological Agency was the most serious on its warning scale; it rated as a "major tsunami", being at least 3 m (9.8 ft) high.[113] The actual height prediction varied, the greatest being for Miyagi at 6 m (20 ft) high.[114] The tsunami inundated a total area of approximately 561 km2 (217 sq mi) in Japan.[115]

The earthquake took place at 14:46 JST (UTC 05:46) around 67 km (42 mi) from the nearest point on Japan's coastline, and initial estimates indicated the tsunami would have taken 10 to 30 minutes to reach the areas first affected, and then areas farther north and south based on the geography of the coastline.[116][117] Just over an hour after the earthquake at 15:55 JST, a tsunami was observed flooding Sendai Airport, which is located near the coast of Miyagi Prefecture,[118][119] with waves sweeping away cars and planes and flooding various buildings as they traveled inland.[120][121] The impact of the tsunami in and around Sendai Airport was filmed by an NHK News helicopter, showing a number of vehicles on local roads trying to escape the approaching wave and being engulfed by it.[122] A 4-metre-high (13 ft) tsunami hit Iwate Prefecture.[123] Wakabayashi Ward in Sendai was also particularly hard hit.[124] At least 101 designated tsunami evacuation sites were hit by the wave.[125]

Like the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, the damage by surging water, though much more localized, was far more deadly and destructive than the actual quake. Entire towns were destroyed in tsunami-hit areas in Japan, including 9,500 missing in Minamisanriku;[126] one thousand bodies had been recovered in the town by 14 March 2011.[127]

Among several factors causing the high death toll from the tsunami, one was the unexpectedly large size of the water surge. The tsunami walls at several of the affected cities were based on much smaller tsunami heights. Also, many people caught in the tsunami thought that they were located on high enough ground to be safe.[128]

Large parts of Kuji and the southern section of Ōfunato including the port area were almost entirely destroyed.[129][130] Also largely destroyed was Rikuzentakata, where the tsunami was three stories high.[131][132][133] Other cities destroyed or heavily damaged by the tsunami include Kamaishi, Miyako, Ōtsuchi, and Yamada (in Iwate Prefecture), Namie, Sōma and Minamisōma (in Fukushima Prefecture) and Shichigahama, Higashimatsushima, Onagawa, Natori, Ishinomaki, and Kesennuma (in Miyagi Prefecture).[134][135][136][137][138][139][140] The most severe effects of the tsunami were felt along a 670-kilometre-long (420 mi) stretch of coastline from Erimo, Hokkaido, in the north to Ōarai, Ibaraki, in the south, with most of the destruction in that area occurring in the hour following the earthquake.[141] Near Ōarai, people captured images of a huge whirlpool that had been generated by the tsunami.[142] The tsunami washed away the sole bridge to Miyatojima, Miyagi, isolating the island's 900 residents.[143] A two-metre-high tsunami hit Chiba Prefecture about 2½ hours after the quake, causing heavy damage to cities such as Asahi.[144]

On 13 March 2011, the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) published details of tsunami observations recorded around the coastline of Japan following the earthquake. These observations included tsunami maximum readings of over 3 m (9.8 ft) at the following locations and times on 11 March 2011, following the earthquake at 14:46 JST:[145]

- 15:12 JST – off Kamaishi – 6.8 m (22 ft)

- 15:15 JST – Ōfunato – 3.2 m (10 ft) or higher

- 15:20 JST – Ishinomaki-shi Ayukawa – 3.3 m (11 ft) or higher

- 15:21 JST – Miyako – 4.0 m (13.1 ft) or higher

- 15:21 JST – Kamaishi – 4.1 m (13 ft) or higher

- 15:44 JST – Erimo-cho Shoya – 3.5 m (11 ft)

- 15:50 JST – Sōma – 7.3 m (24 ft) or higher

- 16:52 JST – Ōarai – 4.2 m (14 ft)

Many areas were also affected by waves of 1 to 3 metres (3.3 to 9.8 ft) in height, and the JMA bulletin also included the caveat that "At some parts of the coasts, tsunamis may be higher than those observed at the observation sites." The timing of the earliest recorded tsunami maximum readings ranged from 15:12 to 15:21, between 26 and 35 minutes after the earthquake had struck. The bulletin also included initial tsunami observation details, as well as more detailed maps for the coastlines affected by the tsunami waves.[146][147]

JMA also reported offshore tsunami height recorded by telemetry from moored GPS wave-height meter buoys as follows:[148]

- offshore of central Iwate (Miyako) – 6.3 m (20 ft)

- offshore of northern Iwate (Kuji) – 6.0 m (18 ft)

- offshore of northern Miyagi (Kesennuma) – 6.0 m (18 ft)

On 25 March 2011, Port and Airport Research Institute (PARI) reported tsunami height by visiting the port sites as follows:[149]

- Port of Hachinohe – 5–6 m (16–19 ft)

- Port of Hachinohe area – 8–9 m (26–29 ft)

- Port of Kuji – 8–9 m (26–29 ft)

- Port of Kamaishi – 7–9 m (23–30 ft)

- Port of Ōfunato – 9.5 m (31 ft)

- Run up height, port of Ōfunato area – 24 m (79 ft)

- Fishery port of Onagawa – 15 m (50 ft)

- Port of Ishinomaki – 5 m (16 ft)

- Shiogama section of Shiogama-Sendai port – 4 m (13 ft)

- Sendai section of Shiogama-Sendai port – 8 m (26 ft)

- Sendai Airport area – 12 m (39 ft)

The tsunami at Ryōri Bay (綾里白浜), Ōfunato was about 30 m high. Fishing equipment was scattered on the high cliff above the bay.[150] At Tarō, Iwate, the tsunami reached a height of 37.9 m (124 ft) up the slope of a mountain some 200 m (656 ft) away from the coastline.[151] Also, at the slope of a nearby mountain from 400 m (1,312 ft) away at Aneyoshi fishery port (姉吉漁港) of Omoe peninsula (重茂半島) in Miyako, Iwate, Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology found estimated tsunami run up height of 38.9 m (127 ft).[30] This height is deemed the record in Japan historically, as of reporting date, that exceeds 38.2 m (125 ft) from the 1896 Meiji-Sanriku earthquake.[152] It was also estimated that the tsunami reached heights of up to 40.5 metres (133 ft) in Miyako in Tōhoku's Iwate Prefecture. The inundated areas closely matched those of the 869 Sanriku tsunami.[153]

A Japanese government study found that only 58% of people in coastal areas in Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima prefectures heeded tsunami warnings immediately after the quake and headed for higher ground. Of those who attempted to evacuate after hearing the warning, only five percent were caught in the tsunami. Of those who didn't heed the warning, 49% were hit by the water.[154]

Elsewhere across the Pacific

Shortly after the earthquake, the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center (PTWC) in Hawaii issued tsunami watches and announcements for locations in the Pacific. At 07:30 UTC, PTWC issued a widespread tsunami warning covering the entire Pacific Ocean.[155][156] Russia evacuated 11,000 residents from coastal areas of the Kuril Islands.[157] The United States National Tsunami Warning Center issued a tsunami warning for the coastal areas in most of California, all of Oregon, and the western part of Alaska, and a tsunami advisory covering the Pacific coastlines of most of Alaska, and all of Washington and British Columbia, Canada.[158][159] In California and Oregon, up to 2.4-metre-high (7.9 ft) tsunami surges hit some areas, damaging docks and harbors and causing over US$10 million in damage.[160] In Curry County, Oregon $7 million in damages occurred including the destruction of 1,100 m (3,600 ft) of dockspace at the Brookings harbor; the county has received over $1 million in FEMA emergency grants.[161] Surges of up to 1 m (3.3 ft) hit Vancouver Island in Canada[159] prompting some evacuations, and causing boats to be banned from the waters surrounding the island for 12 hours following the wave strike, leaving many island residents in the area without means of getting to work.[162][163]

In the Philippines, waves up to 0.5 m (1.6 ft) high hit the eastern seaboard of the country. Some houses along the coast in Jayapura, Indonesia were destroyed.[164] Authorities in Wewak, East Sepik, Papua New Guinea evacuated 100 patients from the city's Boram Hospital before it was hit by the waves, causing an estimated US$4 million in damages.[165] Hawaii estimated damage to public infrastructure alone at US$3 million, with damage to private properties, including resort hotels such as Four Seasons Resort Hualalai, estimated at tens of millions of dollars.[166] It was reported that a 1.5-metre-high (4.9 ft) wave completely submerged Midway Atoll's reef inlets and Spit Island, killing more than 110,000 nesting seabirds at the Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge.[167] Some other South Pacific countries, including Tonga and New Zealand, and U.S. territories American Samoa and Guam, experienced larger-than-normal waves, but did not report any major damage.[168] However, in Guam some roads were closed off and people were evacuated from low-lying areas.[169]

Along the Pacific Coast of Mexico and South America, tsunami surges were reported, but in most places caused little or no damage.[170] Peru reported a wave of 1.5 m (5 ft) and more than 300 homes damaged.[170] The surge in Chile was large enough to damage more than 200 houses,[171] with waves of up to 3 m (9.8 ft).[172][173] In the Galápagos Islands, 260 families received assistance following a 3-metre (9.8 ft) surge which arrived 20 hours after the earthquake, after the tsunami warning had been lifted.[174][175] There was a great deal of damage to buildings on the islands and one man was injured but there were no reported fatalities.[174][176]

The tsunami broke icebergs off the Sulzberger Ice Shelf in Antarctica, 13,000 kilometres (8,100 mi) away. The main iceberg measured 9.5 by 6.5 kilometres (5.9 mi × 4.0 mi) (approximately the area of Manhattan Island) and about 80 metres (260 ft) thick. A total of 125 square kilometres (48 sq mi; 31,000 acres) of ice broke away.[177][178]

As of April 2012, wreckage from the tsunami spread around the oceans, including a soccer ball which was found in Alaska[179] and a Japanese motorcycle found in British Columbia, Canada.[180]

Land subsidence

The Geospatial Information Authority of Japan reported land subsidence based on the height of triangulation stations in the area measured by GPS as compared to their previous values from 14 April 2011.[181]

- Miyako, Iwate – 0.50 m (1.64 ft)

- Yamada, Iwate – 0.53 m (1.73 ft)

- Ōtsuchi, Iwate – 0.35 m (1.14 ft)[182]

- Kamaishi, Iwate – 0.66 m (2.16 ft)

- Ōfunato, Iwate – 0.73 m (2.39 ft)

- Rikuzentakata, Iwate – 0.84 m (2.75 ft)

- Kesennuma, Miyagi – 0.74 m (2.42 ft)

- Minamisanriku, Miyagi – 0.69 m (2.26 ft)

- Oshika Peninsula, Miyagi – 1.2 m (3.93 ft)[182]

- Ishinomaki, Miyagi – 0.78 m (2.55 ft)

- Higashimatsushima, Miyagi – 0.43 m (1.41 ft)

- Iwanuma, Miyagi – 0.47 m (1.54 ft)

- Sōma, Fukushima – 0.29 m (0.95 ft)

Scientists say that the subsidence is permanent. As a result, the communities in question are now more susceptible to flooding during high tides.[183]

Casualties

The National Police Agency has confirmed 15,893 deaths,[184] 6,152 injured,[185] and 2,572 people missing[186] across twenty prefectures.[40]

Of the 13,135 fatalities recovered by 11 April 2011, 12,143 or 92.5% died by drowning. Victims aged 60 or older accounted for 65.2% of the deaths, with 24% of total victims being in their 70s.[187] As of March 2012, Japanese police data showed that 70% of the 3,279 still missing were aged 60 or over, all found, including 893 in their 70s and 577 in their 80s. Of the total confirmed victims, 14,308 drowned, 667 were crushed to death or died from internal injuries, and 145 perished from burns.[188]

Save the Children reports that as many as 100,000 children were uprooted from their homes, some of whom were separated from their families because the earthquake occurred during the school day.[189] 236 children were orphaned in the prefectures of Iwate, Miyagi and Fukushima by the disaster;[190][191] 1,580 children lost either one or both parents,[192] 846 in Miyagi, 572 in Iwate, and 162 in Fukushima.[193] The quake and tsunami killed 378 elementary, middle-school, and high school students and left 158 others missing.[194] One elementary school in Ishinomaki, Miyagi, Okawa Elementary, lost 74 of 108 students and 10 of 13 teachers and staff.[195][196][197]

The Japanese Foreign Ministry has confirmed the deaths of nineteen foreigners.[198] Among them are two English teachers from the United States affiliated with the Japan Exchange and Teaching Program;[199] a Canadian missionary in Shiogama;[200] and citizens of China, North and South Korea, Taiwan, Pakistan and the Philippines.

By 9:30 UTC on 11 March, Google Person Finder, which was previously used in the Haitian, Chilean, and Christchurch, New Zealand earthquakes, was collecting information about survivors and their locations.[201][202] The Next of Kin Registry (NOKR) is assisting the Japanese government in locating next of kin for those missing or deceased.[203]

Japanese funerals are normally elaborate Buddhist ceremonies that entail cremation. The thousands of bodies, however, exceeded the capacity of available crematoriums and morgues, many of them damaged,[204][205] and there were shortages of both kerosene—each cremation requires 50 litres—and dry ice for preservation.[206] The single crematorium in Higashimatsushima, for example, could only handle four bodies a day, although hundreds were found there.[207] Governments and the military were forced to bury many bodies in hastily dug mass graves with rudimentary or no rites, although relatives of the deceased were promised that they would be cremated later.[208]

The tsunami is reported to have caused several deaths outside Japan. One man was killed in Jayapura, Papua, Indonesia after being swept out to sea.[209] A man who is said to have been attempting to photograph the oncoming tsunami at the mouth of the Klamath River, south of Crescent City, California, was swept out to sea.[210][211][212] His body was found on 2 April along Ocean Beach in Fort Stevens State Park, Oregon, some 330 miles (530 km) to the north.[213][214]

Noted individual fatalities within Japan included 104-year-old Takashi Shimokawara, holder of the world athletics records in the men's shot put, discus throw and javelin throw for the over-100s age category. He was killed by the earthquake and tsunami at Kamaishi, Iwate.[215]

As of 27 May 2011, three Japan Ground Self-Defense Force members had died while conducting relief operations in Tōhoku.[216] As of March 2012, the Japanese government had recognized 1,331 deaths as indirectly related to the earthquake, such as caused by harsh living conditions after the disaster.[217] As of 30 April 2012, 18 people had died and 420 had been injured while participating in disaster recovery or clean-up efforts.[218]

Damage and effects

The degree and extent of damage caused by the earthquake and resulting tsunami were enormous, with most of the damage being caused by the tsunami. Video footage of the towns that were worst affected shows little more than piles of rubble, with almost no parts of any structures left standing.[219] Estimates of the cost of the damage range well into the tens of billions of US dollars; before-and-after satellite photographs of devastated regions show immense damage to many regions.[220][221] Although Japan has invested the equivalent of billions of dollars on anti-tsunami seawalls which line at least 40% of its 34,751 km (21,593 mi) coastline and stand up to 12 m (39 ft) high, the tsunami simply washed over the top of some seawalls, collapsing some in the process.[222]

.jpg)

Japan's National Police Agency said on 3 April 2011, that 45,700 buildings were destroyed and 144,300 were damaged by the quake and tsunami. The damaged buildings included 29,500 structures in Miyagi Prefecture, 12,500 in Iwate Prefecture and 2,400 in Fukushima Prefecture.[223] Three hundred hospitals with 20 beds or more in Tōhoku were damaged by the disaster, with 11 being completely destroyed.[224] The earthquake and tsunami created an estimated 24–25 million tons of rubble and debris in Japan.[225][226]

An estimated 230,000 automobiles and trucks were damaged or destroyed in the disaster. As of the end of May 2011, residents of Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima prefectures had requested deregistration of 15,000 vehicles, meaning that the owners of those vehicles were writing them off as unrepairable or unsalvageable.[227]

Ports

All of Japan's ports were briefly shut down after the earthquake, though the ones in Tokyo and southwards soon re-opened. Fifteen ports were located in the disaster zone. The north eastern ports of Hachinohe, Sendai, Ishinomaki and Onahama were destroyed, while the Port of Chiba (which serves the hydrocarbon industry) and Japan's ninth-largest container port at Kashima were also affected, though less severely. The ports at Hitachinaka, Hitachi, Soma, Shiogama, Kesennuma, Ofunato, Kamashi and Miyako were also damaged and closed to ships.[228] All 15 ports reopened to limited ship traffic by 29 March 2011.[229] A total of 319 fishing ports, about 10% of Japan's fishing ports, were damaged in the disaster.[230] Most were restored to operating condition by 18 April 2012.[231]

The Port of Tokyo suffered slight damage; the effects of the quake included visible smoke rising from a building in the port with parts of the port areas being flooded, including soil liquefaction in Tokyo Disneyland's parking lot.[232][233]

Dams and water problems

The Fujinuma irrigation dam in Sukagawa ruptured,[234] causing flooding and washing away five homes.[235] Eight people were missing and four bodies were discovered by the morning.[236][237] Reportedly, some locals had attempted to repair leaks in the dam before it completely failed.[238] On 12 March, 252 dams were inspected and it was discovered that six embankment dams had shallow cracks on their crests. The reservoir at one concrete gravity dam suffered a small non-serious slope failure. All damaged dams are functioning with no problems. Four dams within the quake area were unreachable. When the roads clear, experts will be dispatched to conduct further investigations.[239]

In the immediate aftermath of the calamity, at least 1.5 million households were reported to have lost access to water supplies.[43][240] By 21 March 2011, this number fell dramatically to 1.04 million.[241]

Electricity

According to the Japanese trade ministry, around 4.4 million households served by Tōhoku Electric Power (TEP) in northeastern Japan were left without electricity.[242] Several nuclear and conventional power plants went offline after the earthquake, reducing TEPCO's total capacity by 21 GW.[243] Rolling blackouts began on 14 March due to power shortages caused by the earthquake.[244] The Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), which normally provides approximately 40 GW of electricity, announced that it could only provide about 30 GW. This was because 40% of the electricity used in the greater Tokyo area was supplied by reactors in the Niigata and Fukushima prefectures.[245] The reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi and Fukushima Dai-ni plants were automatically taken offline when the first earthquake occurred and sustained major damage related to the earthquake and subsequent tsunami. Rolling blackouts of approximately three hours were experienced throughout April and May while TEPCO scrambled to find a temporary power solution. The blackouts affected Tokyo, Kanagawa, Eastern Shizuoka, Yamanashi, Chiba, Ibaraki, Saitama, Tochigi, and Gunma prefectures.[246] Voluntary reduced electricity use by consumers in the Kanto area helped reduce the predicted frequency and duration of the blackouts.[247] By 21 March 2011, the number of households in the north without electricity fell to 242,927.[241]

Tōhoku Electric Power was not able to provide the Kanto region with additional power, because TEP's power plants were also damaged in the earthquake. Kansai Electric Power Company (Kepco) cannot share electricity, because its system operates at 60 hertz, whereas TEPCO and TEP operate their systems at 50 hertz; this is due to early industrial and infrastructure development in the 1880s that left Japan without a unified national power grid.[248] Two substations, one in Shizuoka Prefecture and one in Nagano Prefecture, were able to convert between frequencies and transfer electricity from Kansai to Kanto and Tōhoku, but their capacity to do so is limited to 1 GW. With the damage to so many power plants, it may be years before a long-term solution can be found.[249]

In an effort to help alleviate the shortage, three steel manufacturers in the Kanto region contributed electricity produced by their in-house conventional power stations to TEPCO for distribution to the general public. Sumitomo Metal Industries could produce up to 500 MW, JFE Steel 400 MW, and Nippon Steel 500 MW of electric power[250] Auto and auto parts makers in Kanto and Tohoku agreed in May 2011 to operate their factories on Saturdays and Sundays and close on Thursdays and Fridays to assist in alleviating the electricity shortage during the summer of 2011.[251]

Oil, gas and coal

A 220,000-barrel (35,000 m3)-per-day[252] oil refinery of Cosmo Oil Company was set on fire by the quake at Ichihara, Chiba Prefecture, to the east of Tokyo.[253][254] It was extinguished after ten days, injuring six people, and destroying storage tanks.[255] Others halted production due to safety checks and power loss.[256][257] In Sendai, a 145,000-barrel (23,100 m3)-per-day refinery owned by the largest refiner in Japan, JX Nippon Oil & Energy, was also set ablaze by the quake.[252] Workers were evacuated,[258] but tsunami warnings hindered efforts to extinguish the fire until 14 March, when officials planned to do so.[252]

An analyst estimates that consumption of various types of oil may increase by as much as 300,000 barrels (48,000 m3) per day (as well as LNG), as back-up power plants burning fossil fuels try to compensate for the loss of 11 GW of Japan's nuclear power capacity.[259][260]

The city-owned plant for importing liquefied natural gas in Sendai was severely damaged, and supplies were halted for at least a month.[261]

In addition to refining and storage, several power plants were damaged. These include Sendai #4, New-Sendai #1 and #2, Haranomachi #1 and #2, Hirono #2 and #4 and Hitachinaka #1.[262]

Nuclear power plants

The Fukushima Daiichi, Fukushima Daini, Onagawa Nuclear Power Plant and Tōkai nuclear power stations, consisting of a total eleven reactors, were automatically shut down following the earthquake.[263] Higashidōri, also on the northeast coast, was already shut down for a periodic inspection. Cooling is needed to remove decay heat after a Generation II reactor has been shut down, and to maintain spent fuel pools. The backup cooling process is powered by emergency diesel generators at the plants and at Rokkasho nuclear reprocessing plant.[264] At Fukushima Daiichi and Daini, tsunami waves overtopped seawalls and destroyed diesel backup power systems, leading to severe problems at Fukushima Daiichi, including three large explosions and radioactive leakage. Subsequent analysis found that many Japanese nuclear plants, including Fukushima Daiichi, were not adequately protected against tsunami.[265] Over 200,000 people were evacuated.[266]

The 7 April aftershock caused the loss of external power to Rokkasho Reprocessing Plant and Higashidori Nuclear Power Plant but backup generators were functional. Onagawa Nuclear Power Plant lost 3 of 4 external power lines and temporarily lost cooling function in its spent fuel pools for "20 to 80 minutes". A spill of "up to 3.8 litres" of radioactive water also occurred at Onagawa following the aftershock.[267]

A report by the IAEA in 2012 found that the Onagawa Nuclear Power Plant, the closest nuclear plant to the epicenter of the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, had remained largely undamaged. The plant's 3 reactors automatically shut down without damage and all safety systems functioned as designed. The plant's 14-metre-high (46 ft) seawall successfully withstood the tsunami.[268]

Europe's Energy Commissioner Günther Oettinger addressed the European Parliament on 15 March, explaining that the nuclear disaster was an "apocalypse".[269] As the nuclear crisis entered a second month, experts recognized that Fukushima Daiichi is not the worst nuclear accident ever, but it is the most complicated. Nuclear experts stated that Fukushima will go down in history as the second-worst nuclear accident ever.... while not as bad as Chernobyl disaster, worse than Three Mile Island accident. It could take months or years to learn how damaging the release of dangerous isotopes has been to human health and food supplies, and the surrounding countryside.[270]

Later analysis indicated three reactors at Fukushima I (Units 1, 2, and 3) had suffered meltdowns and continued to leak coolant water,[44] and by summer the Vice-minister for Economy, Trade and Industry, the head of the Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency, and the head of the Agency for Natural Resources and Energy, had lost their jobs.[271]

Fukushima meltdowns

Japan declared a state of emergency following the failure of the cooling system at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, resulting in the evacuation of nearby residents.[272][273][274] Officials from the Japanese Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency reported that radiation levels inside the plant were up to 1,000 times normal levels,[275] and that radiation levels outside the plant were up to 8 times normal levels.[276] Later, a state of emergency was also declared at the Fukushima Daini nuclear power plant about 11 km (7 mi) south.[277] This brought the total number of problematic reactors to six.[278]

It was reported that radioactive iodine was detected in the tap water in Fukushima, Tochigi, Gunma, Tokyo, Chiba, Saitama, and Niigata, and radioactive cesium in the tap water in Fukushima, Tochigi and Gunma.[279][280][281] Radioactive cesium, iodine, and strontium[282] were also detected in the soil in some places in Fukushima. There may be a need to replace the contaminated soil.[283] Many radioactive hotspots were found outside the evacuation zone, including Tokyo.[284] Food products were also found contaminated by radioactive matter in several places in Japan.[285] On 5 April 2011, the government of the Ibaraki Prefecture banned the fishing of sand lance after discovering that this species was contaminated by radioactive cesium above legal limits.[286] As late as July 2013 slightly elevated levels of radioactivity were found in beef on sale at Tokyo markets.[287] No death or morbidity has so far been reported as a result of the radioactive emissions.

Incidents elsewhere

A fire occurred in the turbine section of the Onagawa Nuclear Power Plant following the earthquake.[264][288] The blaze was in a building housing the turbine, which is sited separately from the plant's reactor,[272] and was soon extinguished.[289] The plant was shut down as a precaution.[290]

On 13 March the lowest-level state of emergency was declared regarding the Onagawa plant as radioactivity readings temporarily[291] exceeded allowed levels in the area of the plant.[292][293] Tohoku Electric Power Co. stated this may have been due to radiation from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accidents but was not from the Onagawa plant itself.[294]

As a result of the 7 April aftershock, Onagawa Nuclear Power Plant lost 3 of 4 external power lines and lost cooling function for as much as 80 minutes. A spill of a couple of litres of radioactive water occurred at Onagawa.[267]

The number 2 reactor at Tōkai Nuclear Power Plant was shut down automatically.[263] On 14 March it was reported that a cooling system pump for this reactor had stopped working;[295] however, the Japan Atomic Power Company stated that there was a second operational pump sustaining the cooling systems, but that two of three diesel generators used to power the cooling system were out of order.[296]

Wind power

None of Japan's commercial wind turbines, totaling over 2300 MW in nameplate capacity, failed as a result of the earthquake and tsunami, including the Kamisu offshore wind farm directly hit by the tsunami.[297]

Transport

Japan's transport network suffered severe disruptions. Many sections of Tōhoku Expressway serving northern Japan were damaged. The expressway did not reopen to general public use until 24 March 2011.[298][299] All railway services were suspended in Tokyo, with an estimated 20,000 people stranded at major stations across the city.[300] In the hours after the earthquake, some train services were resumed.[301] Most Tokyo area train lines resumed full service by the next day—12 March.[302] Twenty thousand stranded visitors spent the night of 11–12 March inside Tokyo Disneyland.[303]

A tsunami wave flooded Sendai Airport at 15:55 JST,[118] about 1 hour after the initial quake, causing severe damage. Narita and Haneda Airport both briefly suspended operations after the quake, but suffered little damage and reopened within 24 hours.[233] Eleven airliners bound for Narita were diverted to nearby Yokota Air Base.[304][305]

Various train services around Japan were also canceled, with JR East suspending all services for the rest of the day.[306] Four trains on coastal lines were reported as being out of contact with operators; one, a four-car train on the Senseki Line, was found to have derailed, and its occupants were rescued shortly after 8 am the next morning.[307] Minami-Kesennuma Station on the Kesennuma Line was obliterated save for its platform;[308] 62 of 70 (31 of 35) JR East train lines suffered damage to some degree;[229] in the worst-hit areas, 23 stations on 7 lines were washed away, with damage or loss of track in 680 locations and the 30-km radius around the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant unable to be assessed.[309]

There were no derailments of Shinkansen bullet train services in and out of Tokyo, but their services were also suspended.[233] The Tōkaidō Shinkansen resumed limited service late in the day and was back to its normal schedule by the next day, while the Jōetsu and Nagano Shinkansen resumed services late on 12 March. Services on Yamagata Shinkansen resumed with limited numbers of trains on 31 March.[310]

Derailments were minimized because of an early warning system that detected the earthquake before it struck. The system automatically stopped all high-speed trains, which minimized the damage.[311]

The Tōhoku Shinkansen line was worst hit, with JR East estimating that 1,100 sections of the line, varying from collapsed station roofs to bent power pylons, will need repairs. Services on the Tōhoku Shinkansen partially resumed only in Kantō area on 15 March, with one round-trip service per hour between Tokyo and Nasu-Shiobara,[312] and Tōhoku area service partially resumed on 22 March between Morioka and Shin-Aomori.[313] Services on Akita Shinkansen resumed with limited numbers of trains on 18 March.[314] Service between Tokyo and Shin-Aomori was restored by May, but at lower speeds due to ongoing restoration work; the pre-earthquake timetable was not reinstated until late September.[315]

The rolling blackouts brought on by the crises at the nuclear power plants in Fukushima had a profound effect on the rail networks around Tokyo starting on 14 March. Major railways began running trains at 10–20 minute intervals, rather than the usual 3–5 minute intervals, operating some lines only at rush hour and completely shutting down others; notably, the Tōkaidō Main Line, Yokosuka Line, Sōbu Main Line and Chūō-Sōbu Line were all stopped for the day.[316] This led to near-paralysis within the capital, with long lines at train stations and many people unable to come to work or get home. Railway operators gradually increased capacity over the next few days, until running at approximately 80% capacity by 17 March and relieving the worst of the passenger congestion.

Telecommunications

Cellular and landline phone service suffered major disruptions in the affected area.[317] Immediately after the earthquake cellular communication was jammed across much of Japan due to a surge of network activity. On the day of the quake, American broadcaster NPR was unable to reach anyone in Sendai with working phone or Internet.[318] Internet services were largely unaffected in areas where basic infrastructure remained, despite the earthquake having damaged portions of several undersea cable systems landing in the affected regions; these systems were able to reroute around affected segments onto redundant links.[319][320] Within Japan, only a few websites were initially unreachable.[321] Several Wi-Fi hotspot providers reacted to the quake by providing free access to their networks,[321] and some American telecommunications and VoIP companies such as AT&T, Sprint, Verizon,[322] T-Mobile[323] and VoIP companies such as netTALK[324] and Vonage[325] have offered free calls to (and in some cases, from) Japan for a limited time, as did Germany's Deutsche Telekom.[326]

Defense

Matsushima Air Field of the Japan Self-Defense Force in Miyagi Prefecture was struck by the tsunami, flooding the base and resulting in damage to all 18 Mitsubishi F-2 fighter jets of the 21st Fighter Training Squadron.[327][328][329] 12 of the aircraft were scrapped, while the remaining 6 were slated for repair at a cost of 80 billion yen ($1 billion), exceeding the original cost of the aircraft.[330] At the 2nd Regional Headquarters of the Japan Coast Guard in Shiogama, Miyagi, 2 patrol boats were swept away.[331]

Space center

JAXA (Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency) evacuated the Tsukuba Space Center in Tsukuba, Ibaraki. The Center, which houses a control room for part of the International Space Station, was shut down and some damage was reported.[332][333] The Tsukuba control center resumed full operations for the space station's Kibo laboratory and the HTV cargo craft on 21 March 2011.[334]

Cultural properties

754 cultural properties were damaged across nineteen prefectures, including five National Treasures (at Zuigan-ji, Ōsaki Hachiman-gū, Shiramizu Amidadō, and Seihaku-ji); 160 Important Cultural Properties (including at Sendai Tōshō-gū, the Kōdōkan, and Entsū-in, with its western decorative motifs); one hundred and forty-four Monuments of Japan (including Matsushima, Takata-matsubara, Yūbikan, and the Site of Tagajō); six Groups of Traditional Buildings; and four Important Tangible Folk Cultural Properties. Stone monuments at the UNESCO World Heritage Site: Shrines and Temples of Nikkō were toppled.[335][336][337] In Tokyo, there was damage to Koishikawa Kōrakuen, Rikugien, Hamarikyū Onshi Teien, and the walls of Edo Castle.[338] Information on the condition of collections held by museums, libraries and archives is still incomplete.[339] There was no damage to the Historic Monuments and Sites of Hiraizumi in Iwate prefecture, and the recommendation for their inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List in June was seized upon as a symbol of international recognition and recovery.[340]

Aftermath

The aftermath of the earthquake and tsunami included both a humanitarian crisis and a major economic impact. The tsunami resulted in over 340,000 displaced people in the Tōhoku region, and shortages of food, water, shelter, medicine and fuel for survivors. In response the Japanese government mobilized the Self-Defence Forces (under Joint Task Force - Tohoku, led by Lieutenant General Eiji Kimizuka), while many countries sent search and rescue teams to help search for survivors. Aid organizations both in Japan and worldwide also responded, with the Japanese Red Cross reporting $1 billion in donations. The economic impact included both immediate problems, with industrial production suspended in many factories, and the longer term issue of the cost of rebuilding which has been estimated at ¥10 trillion ($122 billion). In comparison to the 1995 Great Hanshin earthquake, the East Japan earthquake brought serious damage to an extremely wide range.[341]

The aftermath of the twin disasters also left Japan's coastal cities and towns with nearly 25 million tons of debris. In Ishinomaki alone, there were 17 trash collection sites 180 metres long and at least 4.5 metres high. An official in the city's government trash disposal department estimated that it would take three years to empty these sites.[342]

In April 2015, authorities off the coast of Oregon discovered debris that is thought to be from a boat destroyed during the tsunami. Cargo contained yellowtail jack fish, a species that lives off the coast of Japan, still alive. KGW estimates that over 1 million tons of debris still remain in the Pacific Ocean.[343]

Humanitarian response

According to Japan's foreign ministry, 116 countries and 28 international organizations offered assistance. Japan specifically requested assistance from teams from Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, and the United States.[344]

Media coverage

Japan's national public broadcaster, NHK, and Japan Satellite Television suspended their usual programming to provide ongoing coverage of the situation.[345] Other nationwide Japanese and international TV networks also broadcast uninterrupted coverage of the disaster. Ustream Asia broadcast live feeds of NHK, Tokyo Broadcasting System, Nippon TV, Fuji TV, TV Asahi, TV Tokyo, Tokyo MX, TV Kanagawa, and CNN on the Internet starting on 12 March 2011.[346] YokosoNews, an Internet webcast in Japan, dedicated its broadcast to the latest news gathered from Japanese news stations, translating them in real time to English.[347]

It was noted that the Japanese news media has been at times overly cautious to avoid panic and reliance on confusing statements by experts and officials.[348]

In this national crisis, the Japanese government provided Japanese Sign Language (JSL) interpreting at the press conferences related to the earthquake and tsunami.[349] Television broadcasts of the press conferences of Prime Minister Naoto Kan and Chief Cabinet Secretary Yukio Edano included simultaneous JSL interpreters standing next to the Japanese flag on the same platform.[350]

According to Jake Adelstein, most Japanese media accepted and parroted the misinformation put out by the Japanese government and TEPCO about the unfolding Fukushima nuclear crisis. Notable exceptions, according to Adelstein, were newspapers Sankei Shimbun and Chunichi Shimbun which questioned the accuracy of the information coming from the government and TEPCO. Because of the unquestioning nature of most Japanese media to hold to the "party line", many Japanese mid-level officials and experts spoke to foreign media to get their opinions and observations publicized.[351]

Atsushi Funahashi, director of Nuclear Nation notes that "when the overseas media was calling Fukushima a ‘meltdown,’ the Japanese government and media waited two months before admitting it."[352]

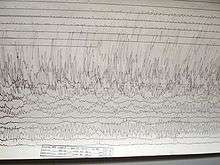

Nine days after the earthquake hit, a visualization and sonification were uploaded to YouTube allowing listeners to hear the earthquake as it unfolded in time. Two days of seismic activity made available by the IRIS Consortium were compressed into two minutes of sound. The large number of views made the video one of the most popular examples of sonification on the web.[353]

Scientific and research response

Seismologists anticipated a very large quake would strike in the same place as the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake — in the Sagami Trough, southwest of Tokyo.[354][355] The Japanese government had tracked plate movements since 1976 in preparation for the so-called Tokai earthquake, predicted to take place in that region.[356] However, occurring as it did 373 km (232 mi) north east of Tokyo, the Tōhoku earthquake came as a surprise to seismologists. While the Japan Trench was known for creating large quakes, it had not been expected to generate quakes above an 8.0 magnitude.[355][356]

The quake gave scientists the opportunity to collect a large amount of data so as to model in great detail the seismic events that took place.[32] This data is expected to be used in a variety of ways, providing as it does unprecedented information about how buildings respond to shaking, and other effects.[357]

Researchers have also analysed the economic effects of this earthquake and have developed models of the nationwide propagation via interfirm supply networks of the shock originated in Tohoku region.[358][359]

See also

- Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster

- Health crisis

- Hideaki Akaiwa

- List of largest earthquakes

- Nuclear power in Japan, section Seismicity

- Ryou-Un Maru

- Seismicity in Japan

Notes

- ↑ In the early days after the earthquake some other names were proposed and used. The Japan Meteorological Agency announced the English name as The 2011 off the Pacific coast of Tōhoku Earthquake.[13][14] NHK[15][16] used Tōhoku Kantō Great Earthquake disaster (東北関東大震災 Tōhoku Kantō Daishinsai); Tōhoku-Kantō Great Earthquake (東北・関東大地震 Tōhoku-Kantō Daijishin) was used by Kyodo News,[17] Tokyo Shimbun[18] and Chunichi Shimbun;[19] East Japan Giant Earthquake (東日本巨大地震 Higashi Nihon Kyodaijishin) was used by Yomiuri Shimbun,[20] Nihon Keizai Shimbun[21] and TV Asahi,[22] and East Japan Great Earthquake (東日本大地震 Higashi Nihon Daijishin) was used by Nippon Television,[23] Tokyo FM[24] and TV Asahi.[25]

- ↑ The 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami has been assigned GLIDE identifier EQ-2011-000028-JPN by the Asian Disaster Reduction Center.[78][79]

References

- 1 2 "震災の揺れは6分間 キラーパルス少なく 東大地震研". Asahi Shimbun. Japan. 17 March 2011. Archived from the original on 18 April 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Magnitude 9.03 – Near The East Coast Of Honshu, Japan". United States Geological Survey (USGS). Archived from the original on 5 April 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 Reilly, Michael (11 March 2011). "Japan's quake updated to magnitude 9.0". New Scientist (Short Sharp Science ed.). Archived from the original on 5 April 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ↑ 震度1以上の余震の最大震度別地震回数表(3月11日~) on 4 March 2015. Japan Meteorological Agency. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ↑ "Damage Situation and Police Countermeasures... 10 September, 2015" National Police Agency of Japan. Retrieved 14 September, 2015. (from "deaths" template)

- ↑ "Damage Situation and Police Countermeasures... 10 March, 2015" National Police Agency of Japan. Retrieved 11 March, 2015. (from "injured" template)

- ↑ "Damage Situation and Police Countermeasures... 10 September, 2015" National Police Agency of Japan. Retrieved 14 September, 2015. (from "missing" template)

- 1 2 "New USGS number puts Japan quake at 4th largest". CBS News. Associated Press. 14 March 2011. Archived from the original on 5 April 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ↑ "Tsunami hits north-eastern Japan after massive quake". BBC News. 12 March 2011. Archived from the original on 12 March 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ↑ Abstract of the 191th meeting of CCEP - website of the Japanese Coordinating Committee for Earthquake Prediction

- ↑ "Press Conference by Prime Minister Naoto Kan". Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet. Archived from the original on 18 April 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- ↑ "Kan names quake at pep talk". The Japan Times. 2 April 2011. Archived from the original on 5 April 2011. Retrieved 2 April 2011.

- ↑ Michael Winter (14 March 2011). "Quake shifted Japan coast about 13 feet, knocked Earth 6.5 inches off axis". USA Today. Archived from the original on 18 April 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ↑ "The 2011 off the Pacific coast of Tohoku Earthquake ~first report~". Japan Meteorological Agency. March 2011. Archived from the original on 13 March 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ↑ "NHKニュース 東北関東大震災(動画)". .nhk.or.jp. Archived from the original on 13 March 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ↑ "仙台放送局 東北関東大震災". .nhk.or.jp. Archived from the original on 12 March 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ↑ "東日本大震災 – 一般社団法人 共同通信社 ニュース特集". Kyodo News. Archived from the original on 18 April 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ 【東京】. "東京新聞:収まらぬ余震 …不安 東北・関東大地震:東京(TOKYO Web)". Tokyo-np.co.jp. Archived from the original on 17 March 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ 【中日新聞からのお知らせ】. "中日新聞:災害義援金受け付け 東日本大震災:中日新聞からのお知らせ(CHUNICHI Web)". Chunichi.co.jp. Archived from the original on 18 April 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ "東日本巨大地震 震災掲示板 : 特集 : YOMIURI ONLINE(読売新聞)". Yomiuri Shimbun. Japan. Archived from the original on 18 April 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ 東日本巨大地震 :特集 :日本経済新聞 (in Japanese). Nikkei.com. 1 January 2000. Archived from the original on 18 April 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ "【地震】東日本巨大地震を激甚災害指定 政府". News.tv-asahi.co.jp. Archived from the original on 17 March 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ "東日本大地震 緊急募金受け付け中". Cr.ntv.co.jp. Archived from the original on 18 April 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ "番組表 – TOKYO FM 80.0 MHz – 80.Love FM RADIO STATION". Tfm.co.jp. Archived from the original on 18 April 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ "「報道特番 ~東日本大地震~」 2011年3月14日(月)放送内容". Kakaku.com. Archived from the original on 17 March 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ USGS Updates Magnitude of Japan’s 2011 Tohoku Earthquake to 9.03 - website of the United States Geological Survey

- ↑ Branigan, Tania (13 March 2011). "Tsunami, earthquake, nuclear crisis – now Japan faces power cuts". The Guardian (London). Archived from the original on 15 March 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ↑ "Japan quake – 7th largest in recorded history". 11 March 2011. Archived from the original on 12 April 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ↑ "March 11th tsunami a record 40.5 metres high NHK". .nhk.or.jp. 13 August 2011. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- 1 2 3 Yomiuri Shimbun evening edition 2-11-04-15 page 15, nearby Aneyoshi fishery port (姉吉漁港)(Google map E39 31 57.8, N 142 3 7.6) 2011-04-15, 大震災の津波、宮古で38.9 m…明治三陸上回る by okayasu Akio (岡安 章夫) Archived 18 April 2011 at WebCite

- 1 2 Roland Buerk (11 March 2011). "Japan earthquake: Tsunami hits north-east". BBC. Archived from the original on 11 March 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Quake shifted Japan by over two metres". Deutsche Welle. 14 March 2011. Archived from the original on 14 March 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Chang, Kenneth (13 March 2011). "Quake Moves Japan Closer to U.S. and Alters Earth's Spin". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 March 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Chai, Carmen (11 March 2011). "Japan's quake shifts earth's axis by 25 centimetres". Montreal Gazette (Postmedia News). Archived from the original on 13 March 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- 1 2 "1-tonne GOCE satellite falls to Earth Sunday night". CBC News. 8 November 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ↑ "Damage Situation and Police Countermeasures... 10 September, 2015" National Police Agency of Japan. Retrieved 14 September, 2015. (from "deaths" template)

- ↑ "Damage Situation and Police Countermeasures... 10 March, 2015" National Police Agency of Japan. Retrieved 11 March, 2015. (from "injured" template)

- ↑ "Damage Situation and Police Countermeasures... 10 September, 2015" National Police Agency of Japan. Retrieved 14 September, 2015. (from "missing" template)

- ↑ "4th Anniversary today". Kobe Shinbun. 11 March 2015. p. 1.

- 1 2 "Damage Situation and Police Countermeasures... February 10, 2014" National Police Agency of Japan. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- ↑ Saira Syed – "Japan quake: Infrastructure damage will delay recovery" – 16 March 2011 – BBC News – Retrieved 18 March 2011. Archived 17 March 2011 at WebCite

- ↑ "Japanese PM: 'Toughest' crisis since World War II". CNN. 13 March 2011. Archived from the original on 12 April 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- 1 2 NPR Staff and Wires (14 March 2011). "Millions Of Stricken Japanese Lack Water, Food, Heat". NPR. Archived from the original on 12 April 2011. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

Nearly 1.5 million households had gone without water since the quake struck.

- 1 2 the CNN Wire Staff (6 June 2011). "Japan: 3 Nuclear Reactors Melted Down – News Story – KTVZ Bend". Ktvz.com. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ↑ "3 nuclear reactors melted down after quake, Japan confirms". CNN. 7 June 2011. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ↑ Molly Hennessy-Fiske (13 March 2011). "Japan earthquake: Insurance cost for quake alone pegged at $35 billion, AIR says". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 13 March 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ↑ Uranaka, Taiga; Kwon, Ki Joon (14 March 2011). "New explosion shakes stricken Japanese nuclear plant". Reuters. Archived from the original on 15 March 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ↑ Zhang, Bo. "Top 5 Most Expensive Natural Disasters in History". AccuWeather.com. News & Video. Archived from the original on 12 April 2011. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- ↑ Victoria Kim (21 March 2011). "Japan damage could reach $235 billion, World Bank estimates". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 12 April 2011. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ↑ Japan earthquake and tsunami: what happened and why|World news. The Guardian. Retrieved on 2011-04-03. Archived 12 March 2011 at WebCite

- ↑ Boadle, Anthony (11 March 2011). "UPDATE 3-USGS upgrades Japan quake to 8.9 magnitude". Reuters. Archived from the original on 18 April 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ↑ "USGS Updates Magnitude of Japan’s 2011 Tohoku Earthquake to 9.0". United States Geological Survey (USGS). 14 March 2011. Archived from the original on 14 March 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ↑ Lovett, Richard A. (14 March 2011). "Japan Earthquake Not the "Big One"?". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on 15 March 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ↑ "地震情報 – 2011年3月10日 15時6分 – 日本気象協会 tenki.jp". Archived from the original on 18 April 2011."地震情報 – 2011年3月11日 15時15分 – 日本気象協会 tenki.jp". Archived from the original on 18 April 2011."地震情報 – 2011年3月11日 15時26分 – 日本気象協会 tenki.jp". Archived from the original on 18 April 2011.

- ↑ "Earthquake Information". Japan Meteorological Agency. Archived from the original on 12 March 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ↑ "Earthquake strikes near Japan's Fukushima nuclear plant; no reports of damage". The Star (Toronto). AP. 2013-10-25. Archived from the original on 2013-10-25. Retrieved 2013-10-25.

A 7.3-magnitude earthquake struck early Saturday morning off Japan's east coast [...] Japan's meteorological agency said the quake was an aftershock of the magnitude-9.0 earthquake and tsunami that struck the same area in 2011.

- 1 2 Marcia McNutt (12 March 2011). Energy from quake: if harnessed, could power L.A. for a year. CBS News via YouTube (Google). Archived from the original on 18 April 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ↑ Foster, Peter. "Alert sounded a minute before the tremor struck". The Daily Telegraph (UK). Archived from the original on 11 March 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ↑ Talbot, David. "80 Seconds of Warning for Tokyo". MIT Technology Review. Archived from the original on 18 April 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ↑ "Ecast Report No.19". Eqh.dpri.kyoto-u.ac.jp. 11 March 2011. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ↑ 報道発表資料平成23年3月29日 (PDF). Japan Meteorological Agency (in Japanese). 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ↑ Sawai, Yuki; Namegaya, Yuichi (9 November 2012). "Challenges of anticipating the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami using coastal geology" (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters 39: L21309. Bibcode:2012GeoRL..3921309S. doi:10.1029/2012GL053692. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ↑ Goto, Kazuhisa; Chagué-Goff, Catherine (29 August 2012). "The future of tsunami research following the 2011 Tohoku-oki event" (PDF). Sedimentary Geology 282: 5, 9, 10. doi:10.1016/j.sedgeo.2012.08.003. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ↑ Minoura, K.; Imamura F., Sugawara D., Kono Y. & Iwashita T. (2001). "The 869 Jōgan tsunami deposit and recurrence interval of large-scale tsunami on the Pacific coast of northeast Japan" (PDF). Journal of Natural Disaster Science 23 (2): 83–88. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- 1 2 Ian Sample (11 March 2011). "newspaper: Japan earthquake and tsunami: what happened and why". The Guardian (London). Archived from the original on 12 March 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ↑ Maugh, Thomas H (11 March 2011). "Size of Japan's quake surprises seismologists". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 18 April 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ↑ "地震調査委 想定外の連動地震 NHKニュース". .nhk.or.jp. Archived from the original on 11 March 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ↑ "時事ドットコム:M8.8、死者300人超=行方不明540人以上−大津波10m・宮城で震度7". Jiji.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ↑ "気象庁"マグニチュードは9.0" NHKニュース". .nhk.or.jp. Archived from the original on 27 March 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ↑ "asahi.com(朝日新聞社):地殻破壊3連鎖、計6分 専門家、余震拡大に警鐘 – 東日本大震災". Asahi Shimbun. Japan. Archived from the original on 18 April 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ↑ Archived 7 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Spatial distribution and focal mechanisms of aftershocks of the 2011 off the Pacific coast of Tohoku Earthquake" by Y. Asano, T. Saito, Y. Ito, K. Shiomi, H. Hirose, T. Matsumoto, S. Aoi, S. Hori, and S. Sekiguchi.

- ↑ "Japan Meteorological Agency | Earthquake Information". Jma.go.jp. Archived from the original on 18 April 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ↑ "Quake | info". Ceme.gsras.ru. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ↑ "The 2011 Japan Earthquake, Tsunami and Nuclear Disaster". October 24, 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- ↑ "USGS.gov: USGS WPhase Moment Solution". Earthquake.usgs.gov. Archived from the original on 13 March 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ↑ Okada Yoshimitsu (President, NIED) (25 March 2011). "Preliminary report of the 2011 off the Pacific coast of Tohoku Earthquake" (PDF). National Research Institute for Earth Science and Disaster Prevention (NIED). Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ↑ "Asian Disaster Reduction Center(ADRC)". Adrc.asia. Archived from the original on 18 April 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ "Asian Disaster Reduction Center (ADRC) Information Sharing on Disaster Reduction". Adrc.asia. Archived from the original on 18 April 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ Erol Kalkan, Volkan Sevilgen (17 March 2011). "March 11, 2011 M9.0 Tohoku, Japan Earthquake: Preliminary results". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 31 March 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ↑ Rincon, Paul (14 March 2011). "How the quake has moved Japan". BBC News. Archived from the original on 14 March 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ↑ Reilly, Michael (12 March 2011). "Japan quake fault may have moved 40 metres". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 12 March 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ↑ Japan seabed shifted 24 metres after March quake | Reuters.com Archived 18 April 2011 at WebCite

- ↑ Jiji Press, "March temblor shifted seabed by 50 metres (160 ft)", Japan Times, 3 December 2011, p. 1.

- 1 2 "Earth's day length shortened by Japan earthquake". CBS News. 13 March 2011. Archived from the original on 13 March 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ↑ Harris, Bethan (14 March 2011). "Can an earthquake shift the Earth's axis?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 14 March 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ↑ Fukue, Natsuko, "Liquefaction driving away Chiba residents", Japan Times, 30 March 2012, p. 3.

- ↑ Fukue, Natsuko, "Urayasu still dealing with liquefaction", Japan Times, 8 April 2011, p. 4. Archived 11 April 2011 at WebCite

- ↑ Yomiuri Shimbun, "Liquefaction Damage Widespread", 10 April 2011.

- ↑ Bloomberg L.P., "Tokyo Disneyland's parking lot shows the risk of reclaimed land", Japan Times, 24 March 2011, p. 3. Archived 18 April 2011 at WebCite

- ↑ Hennessy-Fiske, Molly (13 March 2011). "Volcano in southern Japan erupts". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 13 March 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ↑ Ananthaswamy, Anil (15 March 2011). "Japan quake shifts Antarctic glacier". Archived from the original on 15 March 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ↑ Gross, Richard (19 March 2011). "Japan Earthquake May Have Shifted Earth’s Axis". NPR online.

- ↑ Magnitude 7.1 – NEAR THE EAST COAST OF HONSHU, JAPAN Archived 18 April 2011 at WebCite

- ↑ The CNN Wire Staff (8 April 2011). "Fresh quake triggers tsunami warning in Japan". CNN. Archived from the original on 9 April 2011. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- ↑ "Four dead as new tremor hits Japan disaster zone". Bangkok Post. 8 April 2011. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ↑ Fukushima Nuclear Accident Update Log, IAEA, 7 April 2011 Archived 18 April 2011 at WebCite

- ↑ NHK, "Strong aftershock kills four", 12 April 2011.

- ↑ "Magnitude 6.6 – EASTERN HONSHU, JAPAN". Earthquake.usgs.gov. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ↑ CNN Wire Staff (11 April 2011). "At least 6 killed in new Japan earthquake". CNN World News. Archived from the original on 2 June 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- ↑ 3県で津波観測、注意報を解除 福島沖でM7.1:朝日新聞デジタル (in Japanese). Asahi Broadcasting Corporation. 2013-10-26. Retrieved 2014-07-15.

- ↑ "USGS 10-degree Map Centered at 35°N,140°E of earthquakes of magnitude 4.5 or over". Earthquake.usgs.gov. 2 December 2009. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ↑ "Tohoku, Japan 2011 Tsunami". ngdc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ↑ 気象庁|M5.0以上の余震回数 (in Japanese). Japan Meteorological Agency. Retrieved 2014-07-15.

- ↑ Sugimoto T.; Shinozaki T.; Miyamoto Y. "Aftershocks Associated With Impaired Health Caused by the Great East Japan Disaster Among Youth Across Japan: A National Cross-Sectional Survey Interact J Med Res 2013;2(2):e31". doi:10.2196/ijmr.2585.

- ↑ NHK BS News reported 2011-04-03-02:55 JST

- ↑ "Tsunami bulletin number 3". Pacific Tsunami Warning Center/NOAA/NWS. 11 March 2011. Archived from the original on 12 April 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ↑ Wire Staff (11 March 2011). "Tsunami warnings issued for at least 20 countries after quake". CNN. Archived from the original on 12 March 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ↑ "PTWC warnings complete list". Archived from the original on 12 April 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ↑ "Distance between Dichato, Chile and Sendai, Japan is 17228km". Mapcrow.info. 23 October 2007. Archived from the original on 18 April 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ↑ Attwood, James (12 March 2011). "Chile Lifts Tsunami Alerts After Japan Quake Spawns Waves". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 13 March 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ↑ "Chilean site: (Tsunami) waves penetrated 70–100 m in different parts of the country". Publimetro.cl. Archived from the original on 12 March 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ Tsunami Warning System information, Japan Meteorological Agency Archived 18 April 2011 at WebCite

- ↑ "Tsunami Information (Estimated Tsunami arrival time and Height)". 11 March 2011. Archived from the original on 18 April 2011.

- ↑ 津波による浸水範囲の面積(概略値)について(第5報) (PDF) (in Japanese). Geospatial Information Authority in Japan(国土地理院). 18 April 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 June 2011. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- ↑ One estimate of 10–15 minutes came from German seismologist Rainer Kind of the Helmholtz Research Centre for Geosciences in Potsdam, as interviewed in Japan's tsunami victims only had 15 minutes warning, Deutsche Welle, 12 March 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011. Archived 18 April 2011 at WebCite

- ↑ Another estimate of 15–30 minutes came from Vasily V. Titov, director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Center for Tsunami Research, as reported in Japan tsunami: Toll could rise to more than 1,300, NDTV-hosted copy of an article by Martin Fackler, The New York Times, 12 March 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011. Archived 18 April 2011 at WebCite

- 1 2 "News: Tsunami rolls through Pacific, Sendai Airport under water, Tokyo Narita closed, Pacific region airports endangered". Avherald.com. 6 July 2001. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ↑ Kyodo News (11 March 2011). "10-meter tsunami observed in area near Sendai in Miyagi Pref.". The Japan Times Online. Archived from the original on 2011-10-26. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ↑ "World English". NHK. 12 March 2011. Archived from the original on 18 April 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ↑ "Japan 8.9-magnitude earthquake sparks massive tsunami". Herald Sun (Australia). Associated Press. Archived from the original on 18 April 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ↑ NHK News, ~16:00 JST.

- ↑ "Earthquake, tsunami wreak havoc in Japan". rian.ru. 11 March 2011. Archived from the original on 18 April 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.