Cholera outbreaks and pandemics

Although much is known about the mechanisms behind the spread of cholera, this has not led to a full understanding of what makes cholera outbreaks happen some places and not others. Lack of treatment of human feces and lack of treatment of drinking water greatly facilitate its spread. Bodies of water have been found to serve as a reservoir, and seafood shipped long distances can spread the disease. Cholera did not occur in the Americas for most of the 20th century after the early 1900s in New York City. It reappeared in the Caribbean toward the end of that century and seems likely to persist.[1]

Deaths in India between 1817 and 1860, in the first three pandemics of the nineteenth century, are estimated to have exceeded 15 million people. Another 23 million died between 1865 and 1917, during the next three pandemics. Cholera deaths in the Russian Empire during a similar time period exceeded 2 million.[2]

Pandemics

First, 1816-26

- The first cholera pandemic, though previously restricted, began in Bengal, and then spread across India by 1820. Hundreds of thousands of Indians and ten thousand British troops died during this pandemic.[3] The cholera outbreak extended as far as China, Indonesia (where more than 100,000 people succumbed on the island of Java alone) and the Caspian Sea in Europe, before receding.

Second, 1829-51

- A second cholera pandemic reached Russia (see Cholera Riots), Hungary (about 100,000 deaths) and Germany in 1831; it killed 130,000 people in Egypt that year.[4] In 1832 it reached London and the United Kingdom (where more than 55,000 people died)[5] and Paris. In London, the disease claimed 6,536 victims and came to be known as "King Cholera"; in Paris, 20,000 died (of a population of 650,000), and total deaths in France amounted to 100,000.[6] The epidemic reached Quebec, Ontario, Nova Scotia[7] and New York in the same year, and the Pacific coast of North America by 1834. In the center of the country, it spread through the cities linked by the rivers and steamboat traffic.[8] Cholera afflicted Mexico's populations in 1833 and 1850, prompting officials to quarantine some populations and fumigate buildings, particularly in major urban centers, but nonetheless the epidemics were disastrous.[9]

Over 15,000 people died of cholera in Mecca in 1846.[10] A two-year outbreak began in England and Wales in 1848, and claimed 52,000 lives.[11]

In 1849, a second major outbreak occurred in Paris. In London, it was the worst outbreak in the city's history, claiming 14,137 lives, over twice as many as the 1832 outbreak. Cholera hit Ireland in 1849 and killed many of the Irish Famine survivors, already weakened by starvation and fever.[12] In 1849, cholera claimed 5,308 lives in the major port city of Liverpool, England, an embarkation point for immigrants to North America, and 1,834 in Hull, England.[6]

An outbreak in North America took the life of former U.S. President James K. Polk. Cholera, believed spread from Irish immigrant ship(s) from England, spread throughout the Mississippi river system, killing over 4,500 in St. Louis[6] and over 3,000 in New Orleans.[6] Thousands died in New York, a major destination for Irish immigrants.[6] Cholera claimed 200,000 victims in Mexico.[13]

That year, cholera was transmitted along the California, Mormon and Oregon Trails as 6,000 to 12,000[14] are believed to have died on their way to the California Gold Rush, Utah and Oregon in the cholera years of 1849–1855.[6] It is believed more than 150,000 Americans died during the two pandemics between 1832 and 1849.[15][16]

In 1851, a ship coming from Cuba carried the disease to Gran Canaria. It is considered that more than 6,000 people died in the island during summer, out of a population of 80,000.

During this pandemic, the scientific community varied in its beliefs about the causes of cholera. In France doctors believed cholera was associated with the poverty of certain communities or poor environment. Russians believed the disease was contagious, although doctors did not understand how it spread. The United States believed that cholera was brought by recent immigrants, specifically the Irish, and epidemiologists understand they were carrying disease from British ports. Lastly, some British thought the disease might rise from divine intervention.[17]

Third, 1852-1860

- The third cholera pandemic mainly affected Russia, with over one million deaths. In 1852, cholera spread east to Indonesia, and later was carried to China and Japan in 1854. The Philippines were infected in 1858 and Korea in 1859. In 1859, an outbreak in Bengal contributed to transmission of the disease by travelers and troops to Iran, Iraq, Arabia and Russia.[10] Japan suffered at least seven major outbreaks of cholera between 1858 and 1902. Between 100,000 and 200,000 people died of cholera in Tokyo in an outbreak in 1858-60.[18]

- 1854: An outbreak of cholera in Chicago took the lives of 5.5% of the population (about 3,500 people).[6][19] In 1853–4, London's epidemic claimed 10,739 lives. The Soho outbreak in London ended after the physician John Snow identified a neighborhood Broad Street pump as contaminated and convinced officials to remove its handle.[20] His study proved contaminated water was the main agent spreading cholera, although he did not identify the contaminant. It would take many years for this message to be believed and acted upon. In Spain, over 236,000 died of cholera in the epidemic of 1854–55.[21] The disease reached South America in 1854 and 1855, with victims in Venezuela and Brazil.[13] During the third pandemic, Tunisia, which had not been affected by the two previous pandemics, thought Europeans had brought the disease. They blamed their sanitation practices. Some United States scientists began to believe that cholera was somehow associated with African Americans, as the disease was prevalent in the South in areas of black populations. Current researchers note their populations were underserved in terms of sanitation infrastructure, and health care, and they lived near the waterways by which travelers and ships carried the disease.[22]

Fourth, 1863-1875

The fourth cholera pandemic spread mostly in Europe and Africa. At least 30,000 of the 90,000 Mecca pilgrims died from the disease. Northern Africa was struck in 1865, and the disease reached Zanzibar, where 70,000 died in 1869–70.[23] Cholera claimed 90,000 lives in Russia in 1866.[24] The epidemic of cholera that spread with the Austro-Prussian War (1866) is estimated to have taken 165,000 lives in the Austrian Empire.[25] Hungary and Belgium each lost 30,000 people, and in the Netherlands, 20,000 perished. In 1867, Italy lost 113,000 lives.[26] 80,000 died of the disease in Algeria that year.[23]

- Outbreaks in North America in 1866–1873 killed some 50,000 Americans.[15]

- In London (June 1866[27]), a localized epidemic in the East End claimed 5,596 lives, just as the city was completing construction of its major sewage and water treatment systems (see London sewerage system); the East End section was not quite complete. William Farr, using the work of John Snow, et al., as to contaminated drinking water being the likely source of the disease, relatively quickly identified the East London Water Company as the source of the contaminated water. Quick action prevented further deaths.[6] Also, a minor outbreak occurred at Ystalyfera in South Wales, caused by the local water works using contaminated canal water. Workers associated with the company and their families were most affected, and 119 died. In the same year, more than 21,000 people died in Amsterdam, Netherlands. In the 1870s, cholera spread in the U.S. as an epidemic from New Orleans along the Mississippi River and to ports on its tributaries; thousands of people died.

Fifth, 1881-1896

- The fifth cholera pandemic, according to Dr A. J. Wall, the 1883–1887 part of the epidemic cost 250,000 lives in Europe and at least 50,000 in the Americas. Cholera claimed 267,890 lives in Russia (1892);[28] 120,000 in Spain;[29] 90,000 in Japan and over 60,000 in Persia.[28] In Egypt, cholera claimed more than 58,000 lives. The 1892 outbreak in Hamburg killed 8,600 people. Although the city government was generally held responsible for the virulence of the epidemic, it went largely unchanged. This was the last serious European cholera outbreak, as cities improved their sanitation and water systems.

Sixth, 1899-1923

- The sixth cholera pandemic had little effect in western Europe because of advances in public health, but major Russian cities and the Ottoman Empire were particularly hard hit by cholera deaths. More than 500,000 people died of cholera in Russia from 1900 to 1925, which was also a time of social disruption because of revolution and warfare.[30]

- The 1902–1904 cholera epidemic claimed 200,000 lives in the Philippines[31] including their revolutionary hero and first prime minister Apolinario Mabini. Cholera broke out 27 times during the hajj at Mecca from the 19th century to 1930.[30] The sixth pandemic killed more than 800,000 in India.

- The last outbreak in the United States was in 1910–1911, when the steamship Moltke brought infected people from Naples to New York City. Vigilant health authorities isolated the infected in quarantine on Swinburne Island. Eleven people died, including a health care worker at the hospital on the island.[32][33][34]

- In this time period, because immigrants and travelers often carried cholera from infected locales, the disease became associated with outsiders in each society. The Italians blamed the Jews and gypsies, the British who were in India accused the “dirty natives”, and the Americans saw the problem coming from the Philippines.[35]

Seventh, 1961-1975

- The seventh cholera pandemic began in Indonesia, called El Tor[36] after the strain, and reached East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) in 1963, India in 1964, and the Soviet Union in 1966. From North Africa, it spread into Italy by 1973. In the late 1970s, there were small outbreaks in Japan and in the South Pacific. There were also many reports of a cholera outbreak near Baku in 1972, but information about it was suppressed in the USSR. In 1970, a cholera outbreak struck Sağmalcılar district of Istanbul, then an impoverished slum, claiming more than 50 lives; eventually the incident led to the renaming of the district as present-day Bayrampaşa by the authorities who were harshly criticized. Also in 1970, August, a few cases were reported in Jerusalem.

Notable outbreaks (1991–2009)

- January 1991 – September 1994: Outbreak in South America, apparently initiated when a Chinese ship discharged ballast water. Beginning in Peru,[37] there were 1.04 million identified cases and almost 10,000 deaths. The causative agent was an O1, El Tor strain, with small differences from the seventh pandemic strain. In 1992 a new strain appeared in Asia, a non-O1, nonagglutinable vibrio (NAG), which was named O139 Bengal. It was first identified in Tamil Nadu, India and for a while displaced El Tor in southern Asia. It decreased in prevalence from 1995 to around 10% of all cases. It is considered to be an intermediate between El Tor and the classic strain, and occurs in a new serogroup. Scientists warn of evidence of wide-spectrum resistance by cholera bacteria to drugs such as trimethoprim, sulfamethoxazole and streptomycin.

- An outbreak in Goma, Democratic Republic of Congo in July 1994 claimed 12,000 lives by mid-August. During the worst period, it is estimated that as many as 3,000 people were dying per day from cholera.[38]

- A persistent strain of Gulf Coast cholera, 01, has been found in the brackish waters of marshes in Louisiana and Texas in the United States, leading to a situation of possible transmission by shipments of seafood from those areas to other parts of the country. Medical personnel were advised to think of cholera when assessing symptoms for people who had not been traveling. There have been occurrences in the South but no major outbreaks because of good sanitation and warning systems. It was noted there were more cases in two years from the Latin American epidemic, the El Tor strain, than in 20 years from the Gulf Coast strain.[39]

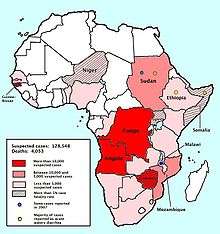

- In 2000, some 140,000 cholera cases were officially reported to WHO. Countries in Africa accounted for 87% of these cases.[40]

- July–December 2007: A lack of clean drinking water in Iraq led to an outbreak of cholera.[41][42] As of 2 December 2007, the UN had reported 22 deaths and 4,569 laboratory-confirmed cases.[43]

- August 2007: The cholera epidemic started in Orissa, India. The outbreak affected Rayagada, Koraput and Kalahandi districts, where more than 2,000 people were admitted to hospitals.[44]

- March–April 2008: 2,490 people from 20 provinces throughout Vietnam were hospitalized with acute diarrhea. Of those hospitalized, 377 patients tested positive for cholera.[45]

- August–October 2008: As of 29 October 2008, a total of 644 laboratory-confirmed cholera cases, including eight deaths, had been verified in Iraq.[46]

- November 2008: Médecins Sans Frontières reported an outbreak of cholera in a refugee camp in the Democratic Republic of the Congo's eastern provincial capital of Goma.[47] Some 45 cases were reportedly treated between November 7 and 9.

- January 2009: The Mpumalanga province of South Africa confirmed over 381 new cases of Cholera, bringing the total number of cases treated since November 2008 to 2276. Nineteen people died in the province since the outbreak.[48]

- August 2008 – April 2009: In the 2008 Zimbabwean cholera outbreak, which continued into 2009, an estimated 96,591 people in the country were infected with cholera and, by 16 April 2009, 4,201 deaths had been reported.[49][50] According to the World Health Organization, during the week of 22–28 March 2009, the "Crude Case Fatality Ratio (CFR)" had dropped from 4.2% to 3.7%.[49] The daily updates for the period 29 March 2009 to 7 April 2009, list 1748 cases and 64 fatalities, giving a weekly CFR of 3.66% (see table above).[51] Those for the period 8 April to 16 April list 1375 new cases and 62 deaths (and a resulting CFR of 4.5%).[51] The CFR had remained above 4.7% for most of January and early February 2009.[52]

Notable outbreaks (2010–present)

- August 2010: Cholera in Nigeria was reaching epidemic proportions after widespread confirmation of the disease outbreaks in 12 of its 36 states. 6400 cases have been reported with 352 reported deaths. The health ministry blamed the outbreak on heavy seasonal rainfall and poor sanitation.[53]

- October 2010 – January 2012, Haiti and Dominican Republic: Late in October 2010, a cholera outbreak was reported in Haiti.[54] As of November 16, the Haitian Health Ministry reported the number of dead to be 1,034, with hospitalizations for cholera symptoms totaling over 16,700.[55] The outbreak was blamed on a camp of Nepalese United Nations peacekeepers, but this was disputed. Scientists have found that Vibrio cholera bacteria can survive between outbreaks in brackish warm water, and it exists in Haitian waterways. The outbreak started on the upper Artibonite River.;[56] people first contracted the disease from this river.[57] In addition, scientists think the hurricane and weather conditions in Haiti worsened the consequences of the outbreak, and damaged sanitation systems allowed it to spread.[56] In the USA, a Florida woman who had recently moved from Haiti had cholera but was effectively treated. Officials noted that US water systems removed the risk of transmission by water supply.[58] By November 2010, the disease had spread into the neighboring Dominican Republic. As of January 2012, the epidemic has sickened nearly 500,000 people and killed nearly 7,000 in Haiti.[59]

- In January 2011, about 411 Venezuelan citizens attended a wedding in the Dominican Republic, where they ate ceviche (raw fish cooked in lemon juice) at the celebration. By the time they returned to Caracas and other Venezuelan cities, some of these travelers were suffering from symptoms of cholera. By January 28, almost 111 cases had been confirmed by the Venezuelan Health Authorities, who quickly set up an 800 number for people to call who wondered whether they were infected. Internationally, Colombia secured its eastern border against immigrants and probable transmission of the disease. Dominican officials started a nationwide study to determine the cause of the outbreak, and warned residents of the imminent danger associated with the consumption of raw fish and shellfish. As of January 29, 2011, none of the cases in Venezuela proved fatal, but two patients were hospitalized. Since the victims had quickly sought help, the outbreak was detected and contained.[60]

- 2011: Nigeria and Democratic Republic of Congo have had outbreaks; the latter has suffered years of disruption from warfare. Somalia has suffered a double hit of cholera and famine, associated with the refugee camps, limited sanitation, and severe drought causing famine and lowered resistance.[61]

- Cholera returned to southern India in 2012, where it was once thought to be eradicated, in relatively affluent Kerala. Toilets were being constructed in an effort to improve sanitation. Ironically, while these toilets were under construction workers defecated and contaminated community wells, causing the outbreak.[62]

- Cholera outbreak in 2011 and 2012 in multiple African nations, in all regions except North Africa, among them Ghana has led to intense campaign for handwashing.[63] In Sierra Leone, some 21,500 cases with 290 deaths have been reported in 2012.[64]

- Since 2010, fatal cholera outbreaks, not just travelers, have been reported in Haiti, Dominican Republic, Cuba, Venezuela, Iraq, Nepal, Pakistan, Iran, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, Afghanistan, India, China, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Kenya, Uganda, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Angola, Somalia, Ethiopia, Ivory Coast, DRC, Congo, Mozambique, Ghana, Guinea, Mali, Ukraine, and Niger.

- On August 21, 2013 the United States State Department issued a security message warning U.S. citizens in or traveling to Cuba about an outbreak of cholera in Havana, that may be linked to a reported outbreak of cholera in eastern Cuba.[65]

- An ongoing cholera outbreak in Ghana in 2014, hitting hard the capital Accra, has claimed some 100 lives and over 11,000 cases by September, but has been largely gone unnoticed as Ebola news in nearby countries has overshadowed it; yet, cholera can kill in hours, considerably faster than Ebola. In 2011 and 2012 Ghana had cholera epidemics combined totaled 16,000 cases and 130 deaths.[66]

- September 2015: Ongoing Cholera epidemic in Tanzania resulting in 13 deaths and almost 1000 cases so far - mainly in Dar es Salaam, but also in Morogoro and Iringa, caused by the O1 Ogawa strain.[67] There had been an earlier outbreak in the lake Tanganyika area, starting in the refugee population who had fled from Burundi. 30 deaths and 4400 cases were reported in May 2015. [68]

False reports

A persistent urban myth states 90,000 people died in Chicago of cholera and typhoid fever in 1885, but this story has no factual basis.[69] In 1885, a torrential rainstorm flushed the Chicago River and its attendant pollutants into Lake Michigan far enough that the city's water supply was contaminated. But, as cholera was not present in the city, there were no cholera-related deaths. As a result of the pollution, the city made changes to improve its treatment of sewage and avoid similar events.

See also

References

- ↑ Blake, PA (1993). "Epidemiology of cholera in the Americas.". Gastroenterology clinics of North America 22 (3): 639–60. PMID 7691740.

- ↑ Beardsley GW (2000). "The 1832 Cholera Epidemic in New York State: 19th Century Responses to Cholerae Vibrio (part 1)". The Early America Review 3 (2). Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- ↑ Pike J (2007-10-23). "Cholera- Biological Weapons". Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD). GlobalSecurity.com. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- ↑ Cholera Epidemic in Egypt (1947).

- ↑ "Asiatic Cholera Pandemic of 1817". Retrieved 2015-01-04.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Charles E. Rosenberg (1987). The cholera years: the United States in 1832, 1849 and 1866. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-72677-0.

- ↑ "Browsing Vol. 14 (1935) by Subject "Epidemic of cholera in Halifax, Nova Scotia....1834 [Title],"". dalspace.library.dal.ca. Retrieved 2015-06-19.

- ↑ Wilford JN (2008-04-15). "How Epidemics Helped Shape the Modern Metropolis". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

On a Sunday in July 1832, a fearful and somber crowd of New Yorkers gathered in City Hall Park for more bad news. The epidemic of cholera, cause unknown and prognosis dire, had reached its peak.

- ↑ Gabriela Soto Laveaga and Claudia Agostoni, "Science and Public Health in the Century of Revolution" in A Companion to Mexican History and Culture, ed. William H. Beezley. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2011, p. 562.

- 1 2 Asiatic Cholera Pandemic of 1846-63. UCLA School of Public Health.

- ↑ Cholera's seven pandemics, cbc.ca, December 2, 2008.

- ↑ The Irish Famine at the Wayback Machine (archived October 27, 2009)

- 1 2 Byrne, Joseph Patrick (2008). Encyclopedia of Pestilence, Pandemics, and Plagues: A-M. ABC-CLIO. p. 101. ISBN 0-313-34102-8.

- ↑ Unruh, John David (1993). The plains across: the overland emigrants and the trans-Mississippi West, 1840–60. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. pp. 408–10. ISBN 0-252-06360-0.

- 1 2 Beardsley GW (2000). "The 1832 Cholera Epidemic in New York State: 19th Century Responses to Cholerae Vibrio (part 2)". The Early America Review 3 (2). Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- ↑ Vibrio cholerae in recreational beach waters and tributaries of Southern California.

- ↑ Hayes, J.N. (2005). Epidemics and Pandemics: Their Impacts on Human History. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. pp. 214–219.

- ↑ Kaoru Sugihara, Peter Robb, Haruka Yanagisawa, Local Agrarian Societies in Colonial India: Japanese Perspectives, (1996), p. 313.

- ↑ Chicago Daily Tribune, 12 July 1854

- ↑ Snow, John (1855). On the Mode of Communication of Cholera.

- ↑ Kohn, George C. (2008). Encyclopedia of Plague and Pestilence: from Ancient Times to the Present. Infobase Publishing. p. 369. ISBN 0-8160-6935-2.

- ↑ Hayes, J.N. (2005). Epidemics and Pandemics: Their Impacts on Human History. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 233.

- 1 2 Byrne, Joseph Patrick (2008). Encyclopedia of Pestilence, Pandemics, and Plagues: A-M. ABC-CLIO. p. 107. ISBN 0-313-34102-8.

- ↑ Eastern European Plagues and Epidemics 1300-1918.

- ↑ Matthew R. Smallman-Raynor PhD and Andrew D. Cliff DSc, Impact of Infectious Diseases on War. .

- ↑ Vibrio Cholerae and Cholera - The History and Global Impact.

- ↑ Johnson, S: The Ghost Map (

- 1 2 Cholera. Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911. p. 265. Retrieved 2010-01-31.

- ↑ "The cholera in Spain". New York Times. 1890-06-20. Retrieved 2008-12-08.

- 1 2 "Cholera (pathology): Seven pandemics". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2009-06-27. Retrieved 2014-06-29.

- ↑ 1900s: The Epidemic years, Society of Philippine Health History.

- ↑ "Cholera Kills Boy. All Other Suspected Cases Now in Quarantine and Show No Alarming Symptoms." (PDF). New York Times. July 18, 1911. Retrieved 2008-07-28.

The sixth death from cholera since the arrival in this port from Naples of the steamship Moltke, thirteen days ago, occurred yesterday at Swineburne Island. The victim was Francesco Farando, 14 years old.

- ↑ "More Cholera in Port". Washington Post. October 10, 1910. Retrieved 2008-12-11.

A case of cholera developed today in the steerage of the Hamburg-American liner Moltke, which has been detained at quarantine as a possible cholera carrier since Monday last. Dr. A.H. Doty, health officer of the port, reported the case tonight with the additional information that another cholera patient from the Moltke is under treatment at Swinburne Island.

- ↑ The Boston Medical and Surgical journal. Massachusetts Medical Society. 1911.

In New York, up to July 22, there were eleven deaths from cholera, one of the victims being an employee at the hospital on Swinburne Island, who had been discharged. The tenth was a lad, seventeen years of age, who had been a steerage passenger on the steamship, Moltke. The plan has been adopted of taking cultures from the intestinal tracts of all persons held under observation at Quarantine, and in this way it was discovered that five of the 500 passengers of the Moltke and Perugia, although in excellent health at the time, were harboring cholera microbes.

- ↑ Hayes, J.N. (2005). Epidemics and Pandemics: Their Impacts on Human History. Santa Barbara CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 349.

- ↑ Sack DA, Sack RB, Nair GB, Siddique AK (January 2004). "Cholera". Lancet 363 (9404): 223–33. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15328-7. PMID 14738797.

- ↑ Nathaniel C. Nash (10 March 1992). "Latin Nations Feud Over Cholera Outbreak". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-02-16.

- ↑ Africa in the Time of Cholera. Retrieved 2015-01-04.

- ↑ P.A. Blake (September 1993). "Epidemiology of cholera in the Americas". Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 22(3) (pmid=7691740): 639–60.

- ↑ Disease fact sheet: Cholera. IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre.

- ↑ James Glanz; Denise Grady (12 September 2007). "Cholera Epidemic Infects 7,000 People in Iraq". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-02-26.

- ↑ "U.N. reports cholera outbreak in northern Iraq". CNN. 2007-08-30. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- ↑ Smith D (2007-12-02). "Cholera crisis hits Baghdad". The Observer (London). Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- ↑ Jena S (2007-08-29). "Cholera death toll in India rises". BBC News. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- ↑ Cholera Country Profile: Vietnam. WHO.

- ↑ "Situation report on diarrhoea and cholera in Iraq". ReliefWeb. 2008-10-29. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- ↑ Sky News Doctors Fighting Cholera In Congo.

- ↑ 381 new cholera cases in Mpumalanga, News24, 24 January 2009.

- 1 2 World Health Organization. Cholera in Zimbabwe: Epidemiological Bulletin Number 16 Week 13 (22-28 March 2009). March 31, 2009.; WHO Zimbabwe Daily Cholera Update, 16 April 2009.

- ↑ "Zimbabwe: Cholera Outbreak Kills 294". The New York Times. Associated Press. 22 November 2008. Retrieved 2011-02-26.

- 1 2 World Health Organization: Zimbabwe Daily Cholera Updates.

- ↑ Mintz & Guerrant 2009

- ↑ Cholera epidemic death toll rises to 352, MSNBC, 25 August 2010.

- ↑ "Haiti’s Latest Misery". The New York Times. 26 October 2010. Retrieved 2011-02-26.

- ↑ "Official: Cholera death toll in Haiti has passed 1,000". msnbc.com. Associated Press. 16 November 2010. Retrieved 2011-02-26.

- 1 2 Aubrey Ann Parker, "Cholera in Haiti: the Climate Connection", Circle of Blue, 2010

- ↑ "WHO, "Final Report of the Independent Panel of Experts on the Cholera Outbreak in Haiti"" (PDF). un.org. Retrieved 2015-06-19.

- ↑ Linda Shrieves, "Cholera case in Orange County poses little risk, experts say", Orlando Sentinel, 29 November 2010

- ↑ McNeil Jr, Donald G. (9 January 2012). "Haitian Cholera Epidemic Traced to First Known Victim". The New York Times.

- ↑ , WRAL

- ↑ Jeffrey Gettleman / New York Times News Service, "U.N.: Cholera scourge now ravaging Somalia", Bend Bulletin, 13 August 2011

- ↑ "The Pioneer". dailypioneer.com. Retrieved 2015-06-19.

- ↑ http://allafrica.com/stories/201210081462.html

- ↑ http://vaccinenewsdaily.com/africa/320429-cholera-outbreak-in-sierra-leone-slows/

- ↑ "State Department Warns U.S. Citizens of Cholera Outbreak in Havana, Cuba". The Weekly Standard. Retrieved 2013-08-21.

- ↑ "Cholera Death Toll Rises To 100". Retrieved 2015-01-04.

- ↑ "Cholera – United Republic of Tanzania". WHO. Retrieved 2015-09-12.

- ↑ "Tanzania cholera epidemic improving". UN. Retrieved 2015-09-12.

- ↑ "Did 90,000 people die of typhoid fever and cholera in Chicago in 1885?". The Straight Dope. 2004-11-12. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

| ||||||||||||||||||||