2008 Atlantic hurricane season

| |

| Season summary map | |

| First system formed | May 31, 2008 |

|---|---|

| Last system dissipated | November 9, 2008 |

| Strongest storm1 | Ike – 935 mbar (hPa) (27.61 inHg), 145 mph (230 km/h) |

| Total depressions | 17 |

| Total storms | 16 |

| Hurricanes | 8 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 5 |

| Total fatalities | 855 direct, 192 indirect |

| Total damage | ~ $47.534 billion (2008 USD) |

| 1Strongest storm is determined by lowest pressure | |

2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010 | |

| Related article | |

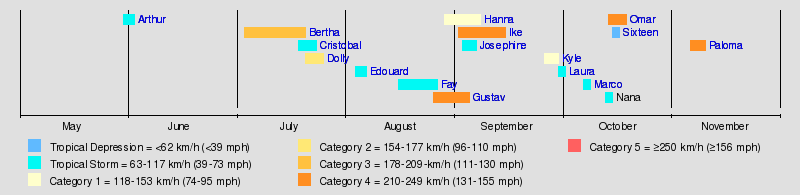

The 2008 Atlantic hurricane season was a very active hurricane season with sixteen named storms formed, including eight that became hurricanes and five that became major hurricanes. The season officially started on June 1 and ended on November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin. However, the formation of Tropical Storm Arthur caused the season to start two days early. This season is the fourth most costly on record, behind only the 2004, 2005 and 2012 seasons, with over $47.5 billion in damage (2008 USD). It was the fourth busiest year since 1944 and the only year on record in which a major hurricane existed in every month from July through November in the North Atlantic.[1] Bertha became the longest lived July tropical cyclone on record for the basin, the first of several long-lived systems during 2008. The season was devastating for Haiti, where over 800 people were killed by four consecutive tropical cyclones (Fay, Gustav, Hanna, and Ike), especially Hanna, in August and September. Hurricane Paloma's outer rain bands also made landfall over Haiti. Ike was also the most destructive storm of the season, as well as the strongest, devastating Cuba as a major hurricane and later making landfall near Galveston, Texas at Category 2 (nearly Category 3) intensity.

One very unusual feat was a streak of tropical cyclones affecting land. All but one system impacted land in 2008. The unprecedented number of storms with impact led to one of the deadliest and destructive seasons in the history of the Atlantic basin, especially with Hurricane Ike, as its overall damages made it the third costliest hurricane in the Atlantic.

Seasonal forecasts

| Source | Date | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes |

| CSU | Average (1950–2000)[2] | 9.6 | 5.9 | 2.3 |

| NOAA | Average (1950–2005)[3] | 11.0 | 6.2 | 2.7 |

| Record high activity | 28 | 15 | 8 | |

| Record low activity | 4 | 2 | 0 | |

| –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– | ||||

| CSU | December 7, 2007 | 13 | 7 | 3 |

| CSU | April 9, 2008 | 15 | 8 | 4 |

| NOAA | May 22, 2008 | 12–16 | 6–9 | 2–5 |

| CSU | June 3, 2008 | 15 | 8 | 4 |

| UKMO | June 18, 2008 | 15* | N/A | N/A |

| CSU | August 5, 2008 | 17 | 9 | 5 |

| NOAA | August 7, 2008 | 14-18 | 7-10 | 3-6 |

| Actual activity | 16 | 8 | 5 | |

| –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– | ||||

| * July–November only: 15 storms observed in this period. | ||||

Forecasts of hurricane activity are issued before each hurricane season by noted hurricane experts Dr. Philip J. Klotzbach, Dr. William M. Gray, and their associates at Colorado State University; and separately by NOAA forecasters.

Dr. Klotzbach's team (formerly led by Dr. Gray) defined the average number of storms per season (1950 to 2000) as 9.6 tropical storms, 5.9 hurricanes, and 2.3 major hurricanes (storms reaching at least Category 3 strength in the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale). A normal season, as defined by NOAA, has 9 to 12 named storms, with 5 to 7 of those reaching hurricane strength, and 1 to 3 major hurricanes.[2][3]

Pre-season forecasts

On December 7, 2007, Klotzbach's team issued its first extended-range forecast for the 2008 season, predicting above-average activity (13 named storms, 7 hurricanes, 3 of Category 3 or higher).[2] On April 9, 2008, the CSU issued a new forecast, anticipating a well above average hurricane season of 15 named storms, 8 hurricanes, and 4 intense hurricanes. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) predicted an above average season with 12 to 16 storms, 6 to 9 hurricanes, and 2 to 5 major hurricanes on May 22.[4][5]

Midseason outlooks

The CSU kept their April 9 forecast on June 3 with 15 storms, 8 hurricanes, and 4 major hurricanes. On June 18 the UK Met Office (UKMO) issued a forecast of 15 tropical storms in the July to November period with a 70% chance that the number would be in the range 10 to 20. However, actual predictions of the number of tropical storms, hurricanes, and major hurricanes were not given.[6] On August 5, following the intense start, the CSU called for 17 storms, 9 hurricanes, and 5 major hurricanes, slightly higher than their prior forecast of 15 storms. On August 7, in response to the season's strong start, NOAA reaffirmed its pre-season outlook of above-average activity. The organization increased its expected probability of such a season to 85% from 65% in its May forecast.[7]

Season summary

The 2008 hurricane season saw the first occurrence of major hurricanes in the months of July through November. Four storms formed before the start of August, and the season also had the earliest known date for three storms to be active on the same day: Hurricane Bertha, and Tropical Storms Cristobal and Dolly were all active on July 20. This season was also one of only nine Atlantic seasons on record to have a major hurricane form before August. This is also the first year four or more Category 4 storms have formed in a single year since 2005, which had 5, and was one of only 7 Atlantic seasons to feature a major hurricane in November.

The season was devastating for Haiti, where over 800 people were killed by four consecutive tropical cyclones (Fay, Gustav, Hanna, and Ike) in August and September. Hurricane Ike was the most destructive storm of the season, as well as the strongest, devastating Cuba as a major hurricane and later making landfall near Galveston, Texas at Category 2 (nearly Category 3) intensity. It caused a particularly devastating storm surge along the western Gulf Coast of the United States due to in part to its large size. Hurricane Hanna was the deadliest storm of the season, killing 537 people, mostly in Haiti. Hurricane Gustav was another very destructive storm, causing up to $6.61 billion in damage to Haiti, Jamaica, the Cayman Islands, Cuba, and the U.S. Hurricane Dolly caused up to $1.35 billion in damage to south Texas and northeastern Mexico. Hurricane Bertha was an early season Cape Verde-type hurricane that became the longest lived pre-August North Atlantic tropical cyclone on record, though it caused few deaths and only minor damage.

Other notable storms in the year included Tropical Storm Arthur, which marked the first recorded time the Atlantic saw a named storm form in May in consecutive years, Tropical Storm Fay, which became the first Atlantic tropical cyclone to make landfall in the same U.S. state on 4 separate occasions; Tropical Storm Marco, the smallest Atlantic tropical cyclone recorded since 1988, Hurricane Omar, a powerful late-season major hurricane which caused moderate damage to the ABC islands, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands in mid-October; and Hurricane Paloma, which became the third-strongest November hurricane in recorded history and caused about $900 million in damage to the Cayman Islands and Cuba. The only storm of the season to not reach tropical storm status, Tropical Depression Sixteen, caused significant flooding in Central America which killed more than 75 people and caused at least $150 million in damages.

Overall, the season's activity was reflected with a total cumulative accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 146.[8] ACE is, broadly speaking, a measure of the power of the hurricane multiplied by the length of time it existed, so storms that last a long time, as well as particularly strong hurricanes, have high ACEs. ACE is only calculated for full advisories on tropical systems at or exceeding 34 knots (39 mph, 63 km/h) or tropical storm strength. Although officially, subtropical cyclones are excluded from the total,[9] the figure above includes periods when storms were in a subtropical phase.

Storms

Tropical Storm Arthur

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | May 31 – June 1 | ||

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 1004 mbar (hPa) | ||

The storm formed late on May 30, 2008, and was designated Tropical Storm Arthur near the Belize coast early on May 31,[10] developing out of the interaction between a tropical wave and the remnants of Tropical Storm Alma, and made landfall on Belize later that day.[10] The system traversed the Yucatán Peninsula slowly and dissipated inland early on June 2.[10] When Arthur made landfall on Belize it caused an estimated US$78 million worth of damage and killed 9 people, 5 of them directly.[10]

Arthur is the first reported tropical storm to form in May since Tropical Storm Arlene in 1981. Other systems have formed, but were subtropical (such as Andrea in 2007). Given Arthur's very short lifespan, Jeff Masters questions whether it would have been reported and named in the years prior to today's technology.[11] The formation of Arthur also marks the first time that a named storm formed in May for two consecutive years.

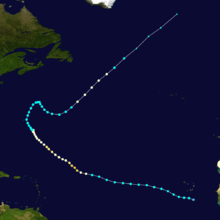

Hurricane Bertha

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | July 3 – July 20 | ||

| Peak intensity | 125 mph (205 km/h) (1-min) 952 mbar (hPa) | ||

Early on July 1, a weak tropical wave emerged off the coast of Africa.[12] By early the next day, a surface low developed and the wave became better organized.[13] The National Hurricane Center upgraded the system to Tropical Depression Two in the morning hours of July 3 after the system was able to maintain convection over its center for at least 12 hours.[14] The depression organized further and developed two distinct bands of convection. Six hours after becoming a depression, it was upgraded to Tropical Storm Bertha, the second named storm of the season.[15] The National Hurricane Center noted that this tropical cyclone was remarkably forecast up to a week in advance by many global computer models.[14]

After a bout of strengthening on July 6, Bertha was upgraded to a hurricane early on July 7 as satellite and microwave imagery indicated an eye feature had formed. It continued to strengthen that morning. Rapid intensification continued that afternoon and Bertha strengthened into a major hurricane with 125 mph (205 km/h) winds and a well-defined eye. The strengthening trend abated early on July 8, due to wind shear, and Bertha rapidly weakened back to a Category 1 hurricane that afternoon.

Bertha again began to rapidly intensify on July 9 as a new eye had formed and the system became more symmetrical. The NHC upgraded Bertha to a Category 2 with winds of 105 mph (170 km/h) and stated that Bertha could intensify further to major hurricane status again, but instead weakened into an 85 mph (135 km/h) Category 1 hurricane.[16] On July 12, Bertha slowed in movement, becoming almost stationary and by July 13 this slow movement weakened the storm to tropical storm strength. The storm brought rain and tropical storm-force winds to Bermuda on July 14, but no damage was reported. After slowly meandering to the east and then the southeast, Bertha regained hurricane strength on the 18th as it began accelerating towards the northeast.[17] As it moved over cooler waters, it weakened slightly to a tropical storm late on July 19. It finally became extratropical on July 20 southwest of Iceland.[18]

Tropical Storm Cristobal

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | July 19 – July 23 | ||

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) 998 mbar (hPa) | ||

A tropical disturbance located off the east coast central Florida formed on July 15. The system slowly developed into a Tropical Depression on July 18 while located 65 mi (105 km) to the south-southeast of Charleston, South Carolina. The depression gradually became better organized and was upgraded to Tropical Storm Cristobal the next day while located 225 mi (362 km) to the southwest of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. Cristobal paralleled the North Carolina coastline for the next two days with minimal to no impact as most of the convection and wind was located on the eastern half of the storm. However, there was some heavy rainfall amounting up to 5 in (130 mm) in localized areas of southern North Carolina. On July 20, Cristobal began to move away from the coastline and began to intensify as it passed over the Gulf Stream. Cristobal peaked the next day with winds of 65 mph (105 km/h). As Cristobal moved closer to Nova Scotia, it began to lose its tropical characteristics. By July 23, Cristobal had transitioned into an extratropical cyclone.[19]

Hurricane Dolly

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | July 20 – July 25 | ||

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min) 963 mbar (hPa) | ||

A strong tropical wave tracked across the Caribbean Sea in the third week of July. Despite producing strong convection and tropical storm-force sustained winds, it failed to develop a low-level circulation until July 20. That morning, reconnaissance aircraft found a low-level circulation and the system was declared Tropical Storm Dolly. This marked the fastest start of a hurricane season since 2005.[20]

It made landfall early on July 21 as a weak and disorganized tropical storm near Cancun, and emerged over the Gulf of Mexico later that morning. 17 deaths were reported in Guatemala from landslides caused by heavy rain on the fringes of Dolly.[21]

On July 22 at 4 p.m. CDT, it strengthened into the second hurricane of the season. It steadily strengthened that night into the morning of July 23 and reached Category 2 intensity. Dolly then weakened some before it made landfall at 1 p.m. CDT (1800 UTC) on South Padre Island as a Category 1 hurricane. Dolly caused no deaths in Texas; it did, however, become the most damaging hurricane to affect Texas since 2005's Hurricane Rita, with US$1.05 billion in damage. It was also the most destructive hurricane to make landfall in Texas since 1983's Alicia, and was the fourth costliest Texas hurricane in history, behind Hurricane Rita, Hurricane Alicia, and Hurricane Ike later in the season. The remnant low caused flash flooding and two deaths in New Mexico before dissipating late on July 27.

Tropical Storm Edouard

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | August 3 – August 6 | ||

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) 996 mbar (hPa) | ||

A shear line stalled in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico in early August as troughing aloft dug into the northeast Gulf of Mexico. This energy aloft helped to organize a surface low along the shearline early on August 2,[22] which slowly organized over the following day. It strengthened into Tropical Depression Five before gaining intensity and being named Tropical Storm Edouard on August 3. The storm made landfall in Southeast Texas near Port Arthur on the morning of August 5 as a strong tropical storm. As it moved inland, the system weakened into a tropical depression by afternoon. The depression dissipated late on August 6 while inland over Texas.

Tropical Storm Fay

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | August 15 – August 27 | ||

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) 986 mbar (hPa) | ||

A vigorous tropical wave tracked into the northeastern Caribbean in mid-August. It produced heavy rain across the Leeward Islands and into Puerto Rico before tracking westward, while unable to develop a low-level circulation despite producing tropical storm-force winds. On August 15, a closed circulation was found and the system was declared Tropical Storm Fay. Later that day Fay produced heavy rains on the island of Hispaniola prompting a major flash flood threat. Fay crossed Hispaniola, Cuba, and hit south Florida beginning late on August 18, slowly tracking northeastward across the peninsula. Significant flooding resulted in much of eastern Florida, along with some wind damage. After crossing into the Atlantic, Fay turned westward again and crossed northern Florida on August 22. As it zigzagged from water to land, it became the first storm in recorded history to make landfall in Florida four times.[23] Fay weakened into a tropical depression along the north coast of the Gulf of Mexico. Fay eventually became extratropical on the morning of August 27 while located over Tennessee. Fay was responsible for 36 deaths and at least $560 million in damage (2008 USD).

Hurricane Gustav

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | August 25 – September 4 | ||

| Peak intensity | 155 mph (250 km/h) (1-min) 941 mbar (hPa) | ||

A tropical wave formed in the coast of Africa on August 18. It intensified into a disturbance whichdeveloped in the deep tropical Atlantic in the fourth week of August. It tracked westward into the Caribbean Sea where it encountered more favorable conditions, and became a tropical depression on the morning of August 25, west of the Windward Islands. It rapidly intensified into Tropical Storm Gustav early that afternoon and into Hurricane Gustav early on August 26. Striking southwest Haiti, it weakened into a tropical storm on the evening of August 27 due to land interaction and slowed down considerably. It re-organized further south into a strong tropical storm once again on August 28 before speeding up and hitting Jamaica. Gustav killed 92 people in Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Jamaica. It then was upgraded to a hurricane again during the late afternoon of August 29. On the morning of August 30, Gustav was upgraded to a major Category 3 hurricane. After intensification slowed for a few hours, another round of rapid intensification occurred and Gustav was upgraded to a Category 4 hurricane during a hurricane hunter flight around 1 p.m. EDT (1700 UTC), with 145 mph (215 km/h) winds. Continuing to intensify, it became a 155 mph storm that afternoon before landfall. Soon after Gustav made landfall in Cuba, firstly on the island of Isla de la Juventud and later on the mainland near Los Palacios in Pinar del Río Province, causing catastrophic damage, although it was difficult to estimate it; damage was later estimated at 3 billion dollars (2008 USD). It then emerged into the Gulf of Mexico on August 30, weakening into a Category 3 hurricane with 115 mph (185 km/h) winds. However, the hurricane was still large, and early the next day, it made landfall on Louisiana. At 8 a.m. CDT September 1 the storm weakened to Category 2 just before landfall. On September 4, Gustav was absorbed by a cold front while over the Ozarks. Gustav is responsible for 153 deaths and at least $6.6 billion in damage.[24]

Hurricane Hanna

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | August 28 – September 7 | ||

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min) 977 mbar (hPa) | ||

Tropical Depression Eight formed on August 28 from a low pressure area east-northeast of the northern Leeward Islands. It was upgraded to a tropical storm later that day and named Hanna. On September 1, while Hanna was moving very near to the island of Mayaguana in the Bahamas, it was upgraded to Category 1 hurricane status. Hanna meandered around the southeastern Bahamas, weakening to a tropical storm while also dumping heavy rain on already-devastated Haiti. Hanna made landfall around Myrtle Beach, SC late on September 5, and quickly northeastward near the east coast of the United States as a tropical storm. Hanna transitioned into an extratropical cyclone as it moved offshore from Massachusetts early on September 7. At least 537 deaths were blamed on Hanna, primarily in Haiti.

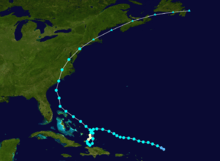

Hurricane Ike

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | September 1 – September 14 | ||

| Peak intensity | 145 mph (230 km/h) (1-min) 935 mbar (hPa) | ||

A tropical disturbance developed off the coast of Africa near the end of August. It tracked south of Cape Verde and slowly developed. On September 1 it became Tropical Depression Nine while west of the Cape Verde islands and intensified into a tropical storm later that day, when it was given the name Ike. Ike developed an eye late on September 3 as it underwent explosive intensification, as it strengthened from a tropical storm to a Category 4 hurricane in twelve hours with an estimated pressure drop of 43 millibars (1.3 inHg), from 991 to 948 millibars (29.3 to 28.0 inHg); and a 24 hour pressure drop of 61 millibars (1.8 inHg), from 996 to 935 millibars (29.4 to 27.6 inHg). Fearing that the new forecast tracks would come to fruition, residents in South Florida prepared for a direct strike from a strong hurricane, with forecasts measuring the storm to be stronger than Hurricane Wilma, which had struck the region three years earlier. Fortunately for Floridians, whose state had endured eight hurricane strikes in the period 2004 - 2005, a strong Bermuda high pressure system pushed Ike toward a more southerly track. Ike weakened to a Category 2 hurricane before re-intensifying back to Category 4. It ripped across Great Inagua Island and Grand Turk Island, where 80% of the buildings on Grand Turk were severely damaged or completely destroyed. It weakened to a strong Category 3 and then re-strengthened to Category 4 late in the afternoon of September 7 as it headed for the northeastern coast of Cuba that evening.[25] In addition, hurricane Ike killed at least 74 people in Haiti and 2 people in the Dominican Republic.[26]

As Ike crossed Cuba on September 8 it weakened to Category 1 and emerged into the Caribbean Sea, where it moved along the southern coast. Ike killed 7 people in Cuba, having traversed nearly the entirety of the island nation. It crossed into the Gulf of Mexico on September 9 and ballooned in size. Ike maintained a double eyewall structure across most of the Gulf of Mexico and continued to expand in size. It made landfall on Galveston Island on September 13 as a strong Category 2 hurricane, but its large size brought a storm surge of over 15 feet (4.6 m) from Galveston Island eastward into southern Louisiana. The Bolivar Peninsula was worst affected by the surge, while Galveston Island (where waves topped the seawall) and the Port Arthur areas also saw extensive damage. Power was knocked out to most of the Houston area and windows were blown out of skyscrapers in downtown Houston. As Ike moved inland, it brought extensive flooding and wind damage throughout the Midwest and as far north as Pennsylvania. Ike was categorized extratropical on September 14.

Damage from Ike is estimated at $37.5 billion (2008 USD) of which $29.5 billion was in the US, the third most destructive U.S. hurricane on record, behind Sandy of 2012 and Katrina in 2005.[27] At least 195 fatalities have been blamed on Ike, of which 112 were in the United States. It was the most destructive hurricane in Texas history. Ike was an extremely large and powerful storm. At one point, the diameter of Ike's tropical storm and hurricane force winds were 600 and 240 miles (965 and 390 km), respectively. Ike also had the highest Integrated Kinetic Energy (IKE) of any Atlantic storm. IKE is a measure of storm surge destructive potential, similar to the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale, though it is more complex and in many ways more accurate. On a scale that ranges from 1 to 6, with 6 being highest destructive potential, Ike registered 5.6.

Ike crossed the U.S. northward into southern Ontario, Canada, releasing copious rainfall which broke records dating back many years, in several cities. It was noted as the second most active tropical storm to have reached the Canadian mainland since Hazel in 1954. Like Ike, Hazel had also affected southern Ontario. The storm dissipated as it reached southern Québec on September 14.[28][29]

Tropical Storm Josephine

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | September 2 – September 6 | ||

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) 994 mbar (hPa) | ||

A tropical disturbance developed off the coast of Africa near the end of August. It tracked south of Cape Verde and slowly developed. On September 2 it became Tropical Depression Ten while south-southeast of the southernmost Cape Verde islands. The depression was upgraded to a tropical storm, "Josephine" later that same day as it passed to the south of the Cape Verde islands. Strong wind shear weakened the system over the next few days, and it dissipated on September 6 without coming near any land. On September 7 the ex-Josephine disturbance regained some organization and regeneration seemed possible, but the low became exposed again and the NHC discontinued their statement about regeneration possibilities. The remnant lingered on for a few days, with a report on September 11 that it might regenerate, but dissipated without further action.

As Josephine passed to the south of the Cape Verde islands on September 2, outer rain bands produced minor rainfall, totaling around 0.55 inches (14 mm).[30] There were no reports of damage or flooding from the rain and overall effects were minor.[31] Several days after the low dissipated, the remnant moisture from Josephine brought showers and thunderstorms to St. Croix where up to 1 in (25.4 mm) of rain fell. The heavy rains led to minor street flooding and some urban flooding. No known damage was caused by the flood.[32]

Hurricane Kyle

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | September 25 – September 29 | ||

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min) 984 mbar (hPa) | ||

A strong tropical disturbance tracked across the northeastern Caribbean Sea in the evening of September 20. It meandered around Puerto Rico and Hispaniola, dumping torrential rains across the islands causing a significant amount of damage, despite never developing a closed circulation. By September 24, it began to track northward away from the islands and into the open Atlantic water, and it became a tropical storm on September 25, thus being named Kyle. Kyle was upgraded to a hurricane during the afternoon of September 27. It continued northward and maintained hurricane strength until landfall near Yarmouth, Nova Scotia in Canada late on September 28. A few hours later, Kyle became extratropical as the cold waters of the Bay of Fundy took effect. In general, Maritimers were spared the anticipated damage.[33]

Tropical Storm Laura

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | September 29 – October 1 | ||

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) 994 mbar (hPa) | ||

In the last week of September, a very large non-tropical system over the north-central Atlantic slowly moved westward away from the Azores. As it entered warmer waters, it slowly gained tropical characteristics and was declared Subtropical Storm Laura early on September 29. It became fully tropical the next day and was reclassified as Tropical Storm Laura. On October 1 it became "post-tropical" as it moved over cooler waters.

Tropical Storm Marco

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | October 6 – October 7 | ||

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) 998 mbar (hPa) | ||

Tropical Depression Thirteen formed from a very small but well-organized low in the Bay of Campeche on October 6. It rapidly intensified into Tropical Storm Marco with 65 mph (100 km/h) winds that afternoon. Marco made landfall near Veracruz, Mexico the next morning at the same intensity. Marco dissipated that night as the small circulation moved inland. At one point, tropical storm-force winds were estimated to extend only 10 miles (16 km) from the center, which makes it the smallest tropical cyclone on record.

Tropical Storm Nana

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | October 12 – October 14 | ||

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min) 1004 mbar (hPa) | ||

A tropical wave exited the coast of Africa on October 6, accompanied by a broad area of low pressure moving westward over the Atlantic Ocean. Initially there was little convection, until October 8 when thunderstorms increased. Three days later, Dvorak classifications began, and following the development of convective banding features on October 12, the NHC reported the low developed into a tropical depression around 0600 UTC; at the time, it was located about 795 mi (1,280 km) west of the Cape Verde Islands.[34] Operationally, the NHC did not begin issuing advisories on the depression until it had become a tropical storm later on October 12, when satellite passes indicated sustained winds of 40 mph (65 km/h);[35] as such, it was named Nana.[34][36][37]

The newly upgraded storm tracked west-northwestward in response to a ridge to its north.[35] Little intensification took place due to increasing wind shear on the western side of the cyclone. The storm attained its lowest pressure of 1004 mbar (hPa; 29.65 inHg) around 0000 UTC on October 13.[34] Within 12 hours of its peak intensity, Nana weakened to a tropical depression as shear continued to displace convection from the center.[34][38] Upon weakening to a depression, it accelerated northwestward.[39] After a brief burst of convection early on October 14,[40] Nana degenerated into a non-convective remnant low pressure area.[41] The remnants persisted until 1200 UTC on October 15, when it dissipated 945 mi (1,520 km) east-northeast of the Leeward Islands.[34]

Hurricane Omar

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | October 13 – October 18 | ||

| Peak intensity | 130 mph (215 km/h) (1-min) 958 mbar (hPa) | ||

A tropical disturbance in the eastern Caribbean Sea was in an area unfavorable for development in the second week of October. While drifting across the region, upper-level winds diminished enough for the tropical disturbance to strengthen and to develop into Tropical Depression Fifteen on October 13. It strengthened to Tropical Storm Omar the next day. Omar quickly strengthened into a 70 mph (110 km/h) storm that afternoon, and became a hurricane that night. It remained a hurricane through that night and it changed little in intensity through the next day, but that evening Omar intensified quickly and became a 115 mph Category 3 storm, and became a 125 mph (205 km/h) storm the next morning. In a discussion supplied by the National Hurricane Center, it stated that Omar may have peaked as a minimal Category 4 early that morning. This was later confirmed in November in their Running Best Track.[42] However, wind shear and dry air quickly weakened Omar to a minimal hurricane that afternoon as it raced towards the northeast and soon it dropped to tropical storm strength. It then degenerated to a remnant low the next day. Omar caused at least $60 million in damage to the Lesser Antilles (2008 USD), and killed two people, both in Puerto Rico.

Tropical Depression Sixteen

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | October 14 – October 15 | ||

| Peak intensity | 30 mph (45 km/h) (1-min) 1004 mbar (hPa) | ||

A vigorous disturbance in the western Caribbean slowly developed off the east coast of Nicaragua. It organized enough to become Tropical Depression Sixteen on October 14. Because the depression hugged the Honduras coast it prevented much strengthening. The disorganized center made landfall in Punta Patuca, Honduras on October 15. It dissipated inland that evening. Its remnants however became nearly stationary in the area between northern Costa Rica and southeastern Mexico and continued to produce locally heavy rains for several days. However, it did not regenerate. This storm caused about $150 million in damage (2008 USD), and killed at least 75 people.

Hurricane Paloma

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | November 5 – November 9 | ||

| Peak intensity | 145 mph (230 km/h) (1-min) 944 mbar (hPa) | ||

An area of low pressure became stationary in the Caribbean Sea without showing tropical development for several days at the beginning of November. Finally, on November 5 the low pressure system organized and became Tropical Depression Seventeen just east of Nicaragua. The next day it strengthened to become Tropical Storm Paloma then later, Hurricane Paloma. The following days proved to be a rarity in terms of tropical cyclone intensity in the month of November. This was seen when Paloma was upgraded to a Category 2, then later a Category 3 major hurricane, making it the first P named storm to reach major hurricane status in the Atlantic Basin. On November 8, the system attained was upgraded to a Category 4 and reached its peak intensity with sustained winds of 145 mph (245 km/h). Thereafter, Paloma began a period of rapid weakening before making landfall as a Category 2 hurricane near Santa Cruz del Sur, Cuba. On November 9, Paloma was downgraded to a tropical storm and then a depression. Later that evening, the storm finally met its demise as it transformed into a remnant low. Paloma caused up to $300 million (2008 USD) in damage to Cuba, and $15 million in damage to the Cayman Islands. In the spring of 2009 the WMO retired the name Paloma, making it the first retired P named storm in the Atlantic Basin.

Storm names

The following names were used for named storms that formed in the North Atlantic in 2008. The list was the same as the 2002 list except for Ike and Laura, which replaced Isidore and Lili, respectively. The names Ike, Omar and Paloma were used for Atlantic storms the first time this year; the name Laura was previously used in 1971. Names that were not used are marked in gray.

Retirement

On April 22, 2009, at the 31st Session of the World Meteorological Organization's Regional Association IV Hurricane Committee, the WMO retired the names Gustav, Ike, and Paloma from its rotating name lists. The names were replaced with Gonzalo, Isaias, and Paulette.[43]

Season effects

This is a table of all of the storms that formed in the 2008 Atlantic hurricane season. It includes their duration, names, landfall(s) – denoted by bold location names – damages, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a wave, or a low, and all of the damage figures are in 2008 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category

at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (millions USD) |

Deaths | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthur | May 31 – June 2 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1004 | Belize, Yucatan Peninsula, Southwestern Mexico | 78 | 5 (4) | |||

| Bertha | July 3 – July 20 | Category 3 hurricane | 125 (205) | 952 | Cape Verde, Bermuda, United States East Coast | Minimal | 3 | |||

| Cristobal | July 19 – July 23 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 998 | Florida, The Carolinas, Atlantic Canada | 0.01 | None | |||

| Dolly | July 20 – July 25 | Category 2 hurricane | 100 (155) | 963 | Guatemala, Yucatan Peninsula (Quintana Roo), Northeastern Mexico, South Texas, New Mexico, Arizona | 1,350 | 1 (21) | |||

| Edouard | August 3 – August 6 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 996 | United States Gulf Coast (Southeast Texas) | 0.25 | 6 | |||

| Fay | August 15 – August 27 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 986 | Leeward Islands, Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Jamaica, Cuba, Southeastern United States (Florida) | 560 | 13 (23) | |||

| Gustav | August 25 – September 4 | Category 4 hurricane | 155 (250) | 941 | Lesser Antilles, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Jamaica, Cayman Islands, Western Cuba, United States Gulf Coast (Louisiana), Midwestern United States | 6,610 | 112 (41) | |||

| Hanna | August 28 – September 7 | Category 1 hurricane | 85 (140) | 977 | Puerto Rico, Turks and Caicos Islands, Bahamas, Haiti, Dominican Republic, United States East Coast (South Carolina), Atlantic Canada | 160 | ≥532 (5) | |||

| Ike | September 1 – September 14 | Category 4 hurricane | 145 (230) | 935 | Dominican Republic, Turks and Caicos Islands, Haiti, Bahamas, Cuba, United States Gulf Coast (Southeast Texas), Midwestern United States, Eastern Canada, Iceland | ≥37,500 | 103 (92) | |||

| Josephine | September 2 – September 6 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 994 | Cape Verde, Leeward Islands | Minimal | None | |||

| Kyle | September 25 – September 29 | Category 1 hurricane | 85 (140) | 984 | Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Bermuda, New England, The Maritimes (Nova Scotia) | 57.1 | 8 | |||

| Laura | September 29 – October 1 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 994 | British Isles, Netherlands, Norway | Minimal | None | |||

| Marco | October 6 – October 7 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 998 | Eastern Mexico (Veracruz) | Minimal | None | |||

| Nana | October 12 – October 14 | Tropical storm | 40 (65) | 1004 | None | None | None | |||

| Omar | October 13 – October 18 | Category 4 hurricane | 130 (215) | 958 | Leeward Antilles, Venezuela, Leeward Islands, Puerto Rico | 79 | 0 (1) | |||

| Sixteen | October 14 – October 15 | Tropical depression | 30 (45) | 1004 | Honduras, Belize | ≥150 | ≥75 | |||

| Paloma | November 5 – November 10 | Category 4 hurricane | 145 (230) | 944 | Nicaragua, Honduras, Cayman Islands, Jamaica, Cuba, Bahamas, Florida | 454.5 | 0 (1) | |||

| Season Aggregates | ||||||||||

| 17 cyclones | May 30 – November 9 | 155 (250) | 935 | ≥47,099 | ≥858 (188) | |||||

See also

- List of Atlantic hurricanes

- List of Atlantic hurricane seasons

- 2008 Pacific hurricane season

- 2008 Pacific typhoon season

- 2008 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 2007–08, 2008–09

- Australian region cyclone seasons: 2007–08, 2008–09

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 2007–08, 2008–09

References

- ↑ Azadeh Ansari and Reynolds Wolf (2008-12-01). "An unusually destructive hurricane season ends". CNN. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-01.

- 1 2 3 Philip J. Klotzbach and William M. Gray (2007-12-07). "Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and U.S. Landfall Strike Probability for 2008" (PDF). Colorado State University. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- 1 2 Climate Prediction Center (2006-08-08). "BACKGROUND INFORMATION: THE NORTH ATLANTIC HURRICANE SEASON". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 2010-11-15. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- ↑ Neale, Rick, Experts predict 'very active' Atlantic hurricane season, USA Today. Retrieved 2008-04-09.

- ↑ Klotzbach, Philip J. Klotzbach and William M. Gray EXTENDED RANGE FORECAST OF ATLANTIC SEASONAL HURRICANE ACTIVITY AND U.S. LANDFALL STRIKE PROBABILITY FOR 2008 (as of 9 April 2008), Department of Atmospheric Science, Colorado State University. Retrieved 2008-04-09.

- ↑ "UKMO North Atlantic tropical storms seasonal forecast for 2008". Retrieved 26 September 2009.

- ↑ NHC (2008-08-07). "Strong Start Increases NOAA’s Confidence for Above-Normal Atlantic Hurricane Season". NOAA. Archived from the original on 8 August 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-08.

- ↑ Hurricane Research Division (March 2011). "Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2011-07-23.

- ↑ David Levinson (2008-08-20). "2005 Atlantic Ocean Tropical Cyclones". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 2011-07-23.

- 1 2 3 4 Blake (2008-07-28). "Tropical Storm Arthur Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). NHC. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-23.

- ↑ Jeff Masters (2008-07-28). "The hurricane season of 2008 rings in with gender-confused Arthur". Weather Underground. Retrieved 2008-08-23.

- ↑ Blake (2008). "July 1 6z Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on August 4, 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-04.

- ↑ Cangialosi (2008). "July 2 2:05a EDT Tropical Weather Discussion". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on August 4, 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-04.

- 1 2 Blake (2008). "Tropical Depression Two Advisory 1 Discussion". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 3 August 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-04.

- ↑ Brown (2008). "Tropical Depression Two Advisory 2 Discussion". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 3 August 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-04.

- ↑ Rhome (2008). "Hurricane Bertha Public Advisory 27". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 12 July 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- ↑ Blake (2008). "Hurricane Bertha Public Advisory 63". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 1 August 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- ↑ National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division (June 4, 2015). "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ↑ Avila/Beven/Blake/Brown/Pasch (2008-08-01). "Atlantic Tropical Summary for the Month of July". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 3 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-04.

- ↑ National Hurricane Center. Atlantic Hurricane Database. Retrieved on 2008-07-21.

- ↑ Staff writer (2008-07-21). "Tropical storm Dolly kills 12 in Guatemala". Radio Netherlands Worldwide. Archived from the original on July 27, 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-21.

- ↑ Tropical Prediction Center. Surface Analysis: August 2, 1200 UTC. Retrieved on 2008-08-03.

- ↑ "Fay's 4th Florida landfall is one for record books", By BRENDAN FARRINGTON, Associated Press Writer, August 23, 2008

- ↑ Jindal, Landrieu Urge Congress Aid For Hurricanes Gustav, Ike Archived July 16, 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Ike makes landfall in Cuba as Category 3 hurricane". CNN.

- ↑ MSNBC - Hurricane Ike begins lashing Cuba

- ↑ "Wunder Blog : Weather Underground". Wunderground.com. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ Powell, Mark (2008-09-11). "Ike Integrated Kinetic Energy.". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Retrieved 2008-09-27.

- ↑ Masters, Jeff (2008-09-11). "Ike's storm surge extremes.". Weather Underground. Retrieved 2008-09-27.

- ↑ Computer Generated (2008-09-02). "Weather History for Praia, Cape Verde, September 2". Wunderground. Retrieved 2008-09-14.

- ↑ Knabb (2008-09-02). "Tropical Depression Ten Public Advisory One". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 8 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-04.

- ↑ Stuart Hinson (2008). "NCDC Event Report: Heavy Rain". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ globesports.com: Kyle fizzles over Fundy

- 1 2 3 4 5 Stacy R. Stewart (November 28, 2008). "Tropical Storm Nana Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 May 2009. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- 1 2 Brown (October 12, 2008). "Tropical Storm Nana Discussion One". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 11 May 2009. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- ↑ Associated Press (October 12, 2008). "Tropical Storm Nana expected to weaken". USA Today. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- ↑ Staff Writer (October 12, 2008). "Tropical Storm Nana Forms in Eastern Atlantic". Fox News. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- ↑ Staff Writer (October 13, 2008). "Tropical Storm Nana Fades but New Systems Develop". Reuters. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- ↑ Brown (October 13, 2008). "Tropical Depression Nana Discussion Five". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 11 May 2009. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- ↑ Rhome (October 14, 2008). "Tropical Depression Nana Discussion Six". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 11 May 2009. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- ↑ Blake (October 14, 2008). "Tropical Depression Nana Discussion Seven (Final)". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 11 May 2009. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- ↑ ftp://ftp.tpc.ncep.noaa.gov/atcf/tcweb/invest_al152008.invest

- ↑ "Gustav, Ike, and Paloma retired". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. April 22, 2009. Archived from the original on 2009-08-11. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

External links

- Satellite movie of 2008 Atlantic hurricane season

- HPC rainfall page for 2008 Tropical Cyclones

- National Hurricane Center Website

- National Hurricane Center's Atlantic Tropical Weather Outlook

| |||||||||||||