Hugh Grosvenor, 1st Duke of Westminster

| His Grace The Duke of Westminster KG PC JP | |

|---|---|

| |

| Master of the Horse | |

|

In office 3 May 1880 – 9 June 1885 | |

| Monarch | Queen Victoria |

| Prime Minister | William Ewart Gladstone |

| Preceded by | The Earl of Bradford |

| Succeeded by | The Earl of Bradford |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 13 October 1825 |

| Died | 22 December 1899 |

| Nationality | British |

| Political party | Liberal |

| Spouse(s) |

(1) Lady Constance Leveson-Gower (d. 1880) (2) Hon. Katherine Cavendish (1857–1941) |

| Alma mater | University of Oxford |

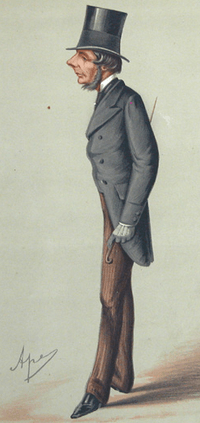

Hugh Lupus Grosvenor, 1st Duke of Westminster, KG, PC, JP (13 October 1825 – 22 December 1899), styled Viscount Belgrave between 1831 and 1845 and Earl Grosvenor between 1845 and 1869 and known as The Marquess of Westminster between 1869 and 1874, was an English landowner, politician and racehorse owner.

He inherited the estate of Eaton Hall in Cheshire and land in Mayfair and Belgravia, London, and spent much of his fortune in developing these properties. Although he was a member of parliament from the age of 22, and then a member of the House of Lords, his main interests were not in politics, but rather in his estates, in horse racing, and in country pursuits. He developed the stud at Eaton Hall and achieved success in racing his horses, winning the Derby on four occasions. Grosvenor also took an interest in a range of charities. At his death he was considered to be the richest man in Britain.

Personal life

Hugh Lupus Grosvenor was the second and eldest surviving son of Richard Grosvenor, 2nd Marquess of Westminster and Lady Elizabeth Leveson-Gower, the younger daughter of George Leveson-Gower, the 2nd Marquess of Stafford and later the 1st Duke of Sutherland. He was educated at Eton College and, until 1847, at Balliol College, Oxford. He left Oxford without taking a degree to become Member of Parliament (MP) for Chester. This seat had been held by his uncle, Robert Grosvenor (later the 1st Baron Ebury), who decided to move to one of the two unopposed Middlesex seats. In 1851 he toured India and Ceylon. The following year, on 28 April, he married his first cousin, Lady Constance Sutherland-Leveson-Gower, the fourth daughter of the 2nd Duke of Sutherland;[1] at the time of the wedding she was aged 17.[2] The wedding was held in the Chapel Royal in St. James's Palace, London, and was attended by Queen Victoria and Albert.[1] Constance's mother had been Mistress of the Robes to Queen Victoria and a "favourite" of the queen.[2] Their first child, a son, was born in 1853, and Queen Victoria became his godmother. By 1874 the couple had eleven children, eight of whom survived into adulthood; five sons and three daughters.[1]

In 1880 Constance died from Bright's disease (nephritis). Two years later, in June 1882, Grosvenor married Katherine Caroline, the third daughter of the 2nd Baron Chesham and Henrietta Frances Lascelles, who was then aged 24; she was younger than the duke's eldest son and two of his daughters. They had four children, two sons and two daughters.[1]

Family

The eight children from the first marriage who survived into adulthood were:

- Victor Alexander Grosvenor, Earl Grosvenor (28 April 1853 – 22 January 1884), who married Lady Sibell Mary Lumley, the daughter of Richard George Lumley, 9th Earl of Scarbrough and Frederica Mary Adeliza Drummond. He was the father of Hugh Grosvenor, 2nd Duke of Westminster

- Lady Elizabeth Harriet (11 October 1856 – 25 March 1928), who married James Butler, 3rd Marquess of Ormonde.

- Lady Beatrice Constance (14 November 1858 – 12 January 1911), who married her stepmother's nephew Charles Cavendish, 3rd Baron Chesham in 1877.

- Lieutenant-Colonel Lord Arthur Hugh (31 May 1860 – 29 April 1929), who married Helen, the daughter of Sir Robert Sheffield, 5th Baronet.

- Lord Henry George (23 June 1861 – 27 December 1914), who married, first, Dora Mina, the daughter of James Erskine-Wemyss, and was the father of William Grosvenor, 3rd Duke of Westminster; and second, Rosamund Angharad, the daughter of Edward Lloyd.

- Lord Robert Edward (19 March 1869 – 16 June 1888), who died unmarried.

- Margaret Evelyn (9 April 1873 – 27 March 1929), who married Adolphus Cambridge, 1st Marquess of Cambridge.

- Captain Lord Gerald Richard (14 July 1874 – 10 October 1940), who died unmarried.[3]

The four children from his second marriage were:

- Lady Mary Cavendish (12 May 1883 – 14 January 1959), who married, first Henry Crichton, Viscount Crichton (1872–1914), and was the mother of John Crichton, 5th Earl Erne; and second, Colonel the Hon. Algernon Francis Stanley (1874–1962).

- Lord Hugh William (6 April 1884 – 30 October 1914), who married Lady Mabel Florence Mary, the daughter of John Crichton, 4th Earl Erne, and who was the father of Gerald Grosvenor, 4th Duke of Westminster and Robert Grosvenor, 5th Duke of Westminster. He was killed in action in the First World War.

- Lady Helen Frances (5 February 1888 – 21 October 1970), who married Brigadier-General Lord Henry Seymour (1878–1939) and was the mother of Hugh Seymour, 8th Marquess of Hertford.

- Lord Edward Arthur (27 October 1892 – 26 August 1929), who married Lady Dorothy Margaret, the daughter of Valentine Browne, 5th Earl of Kenmare.[3]

Political and public life

Grosvenor was elected as Whig MP for Chester in 1847 and continued to represent that constituency until, on the death of his father in 1869, he succeeded as 3rd Marquess of Westminster and entered the House of Lords. His maiden speech in the Commons was made in 1851 in a debate on disorders in Ceylon, shortly following his tour of the country. Otherwise he took little interest in the affairs of the House of Commons until 1866 when he expressed his opposition to Gladstone's Reform Bill. This played a part in Gladstone's resignation, the election of the Conservative Derby government and Disraeli's Second Reform Act. The relationship between Grosvenor and Gladstone later improved and in Gladstone's resignation honours in 1874, Grosvenor was created the 1st Duke of Westminster. When Gladstone became Prime Minister again in 1880, he appointed Grosvenor as Master of the Horse, a position appropriate to his interests in horse racing but "not an actively political office".[1] In the 1880s Grosvenor disagreed with Gladstone again, this time about Home Rule for Ireland. During this dispute, Grosvenor sold his portrait of Gladstone that had been painted by Millais. Ten years later they were again reconciled when they both opposed atrocities by the Turks against the Armenians.[4] When Gladstone died in 1898, Grosvenor presided over a Gladstone National Memorial committee that commissioned statues of him, and rebuilt Gladstone's St Deiniol's Library at Hawarden in north Wales.[1]

In 1860 Grosvenor formed the Queen's Westminster Rifle Volunteers and became its Lieutenant Colonel. He led the Cheshire Yeomanry as Colonel Commandant from 1869.[5] He also supported charities; at one time or another, he was the president of five London hospitals, the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, the Metropolitan Drinking Fountain and Cattle Trough Association, the Gardeners' Royal Beneficent Association, the Hampstead Heath Protection Society, the Early Closing Association, the United Committee for the Demoralization of Native Races by the Liquor Traffic, and the Royal Agricultural Society. He was a member of the Council for the Promotion of Cremation; at that time cremation was unpopular with the Church.[1] Grosvenor was chairman of the Queen's Jubilee Nursing Fund, an organisation that provided district nurses for the sick poor, through which he became associated with Florence Nightingale.[6] In 1883 he was appointed as Lord Lieutenant of Cheshire, and when the London County Council was created in 1888, he became the first Lord Lieutenant of the County of London.[1]

Development of the estates

The Grosvenor country estate is at Eaton Hall in Cheshire. When Grosvenor inherited the estate it was worth at least £152,000 (£12,540,000 as of 2016),[7] a year. After inheriting the estate, one of his first acts was to commission a statue of his namesake, the Norman Hugh Lupus, who had been the 1st Earl of Chester, from G. F. Watts, to stand in the forecourt of the hall.[1] In 1870 Grosvenor commissioned Alfred Waterhouse to design a new house to replace the previous hall designed by William Porden and extended by William Burn. The core of the previous hall was retained, parts were completely rebuilt and other parts were refaced and remodelled. A private wing was built as a residence for the family, and this was connected to the main hall by a corridor. Waterhouse also designed Eaton Chapel and its associated clocktower, and redesigned the stables.[8] It is said that the hall's guests "were not greatly amused" by the carillon of 28 bells that played 28 tunes and sounded every quarter of the hour during the day and the night.[1] The work took 12 years to complete and it cost £803,000 (£72,230,000 as of 2016).[2][7] The hall has been described as "the most ambitious instance of Gothic Revival domestic architecture anywhere in the country",[8] and as "a vast, cheerless, Gothic structure".[1]

Grosvenor paid for many buildings on his estates. He was a patron of the Chester architect John Douglas. Douglas' biographer, Edward Hubbard, estimated that the duke commissioned four churches and chapels, eight large houses, about 15 schools and institutions, about 50 farms (in whole or part), about 300 cottages, lodges, smithies and the like, two cheese factories, two inns, and about 12 commercial buildings (for most of which Douglas was the architect) – and these were just the buildings in the city of Chester and on the Eaton estate.[9] He commissioned G. F. Bodley to rebuild St Mary's Church in his Cheshire estate village of Eccleston, which was completed in 1899, the year of his death.[10] He also spent money on Grosvenor House in London and Cliveden in Buckinghamshire, which he had inherited on the death of his mother-in-law. He built shooting lodges on sporting estates in Sutherland, in Scotland, that he rented from his cousin, the Duke of Sutherland.[1]

The Grosvenor wealth came mainly from the ground rents of Mayfair and Belgravia in London; these grew from about £115,000 (£9,830,000 as of 2016) in 1870 to about £250,000 (£25,130,000 as of 2016)[7] annually in 1899. He oversaw much rebuilding in Mayfair and commissioned architects, such as Norman Shaw, Aston Webb and Alfred Waterhouse to design new buildings. He held his own opinions on architectural styles and decoration, favouring the Queen Anne style rather than the Italianate stucco preferred by his father; for red brick and terracotta; for stucco to be painted bright orange, and railings in chocolate or red; and for Oxford Street to be paved with wooden blocks. He opposed the use of telegraph poles and wires, and would not allow any building work during the London season. He encouraged the provision of more urinals, both on his estates and in London generally, and has been described as a "one-man planning and enforcement officer".[1]

Personality and personal interests

Grosvenor's major interest was in horse racing. In 1875 he established a racing stable at Eaton, eventually employing 30 grooms and boys, with two or three stallions and about 20 breeding mares. He regarded this, not so much as an extravagance, but rather as an aristocratic duty. He never gambled or placed a bet on any of his horses. In 1880, one of his horses, Bend Or, ridden by Fred Archer, won the Derby, and he had more Derby successes in 1882, 1886, and 1899. With his successes and sale of horses, it is considered possible that this enterprise was self-financing. Grosvenor took an interest in the country pursuits of deer stalking and shooting, both in the Scottish Highlands and on his Cheshire estate and added to the family's art collection. Grosvenor was teetotal and a supporter of temperance. In his Mayfair estate he reduced the number of public houses and beerhouses from 47 to eight.[1]

Final year and death

In 1899, the last year of his life, he supported the Seats for Shops Assistants Bill (to reduce cruelty to women employees), stalked a stag in Scotland, shot 65 snipe in 1½ hours in Aldford on his Cheshire estate, and attended the wedding of one of his granddaughters.[11] Later that year, while visiting the same granddaughter in Cranborne, Dorset, he developed bronchitis, from which he died.

He was cremated in Woking Crematorium and his ashes were buried in the churchyard of Eccleston Church, Cheshire. The 1st Duke of Westminster had two cenotaphs erected in his honour, one in the Grosvenor Chapel of Eccleston Church and another in the south transept of Chester Cathedral.

He was succeeded as Duke of Westminster by his grandson, Hugh. At his death he was "reputedly the wealthiest man in Britain"; his estate for the purposes of probate was £594,229 (£59.7 million as of 2016),[7] and his real estate (entailed therefore not included in his personal estate under the law of that time) was valued at about £6,000,000.[1]

-

Grosvenor Chapel at Eccleston Church: Cenotaph and Garter Banner of the 1st Duke of Westminster

-

South transept at Chester Cathedral: Cenotaph of the 1st Duke of Westminster (detail)

-

.jpg)

Grave of Hugh Grosvenor, 1st Duke of Westminster

-

Grave of Constance Gertrude (née Leveson-Gower), first wife of the 1st Duke of Westminster

-

Grave of Katherine Caroline (née Cavendish), second wife of the 1st Duke of Westminster

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Thompson, F. M. L., (2004) (online edition 2006) 'Grosvenor, Hugh Lupus, first duke of Westminster (1825–1899)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Retrieved on 26 April 2010. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- 1 2 3 Newton & Lumby 2002, p. 27.

- 1 2 Lundy, Darryl (2010), Hugh Lupus Grosvenor, 1st Duke of Westminster, thePeerage.com, p. 10855, retrieved 7 June 2010

- ↑ Newton & Lumby 2002, pp. 36–37.

- ↑ Newton & Lumby 2002, p. 29.

- ↑ Newton & Lumby 2002, p. 36.

- 1 2 3 4 UK CPI inflation numbers based on data available from Gregory Clark (2015), "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)" MeasuringWorth.

- 1 2 Anon. (2002), Eaton Halls, Eaton: Eaton Estate, p. 6

- ↑ Hubbard 1991, pp. 63–64.

- ↑ Pevsner & Hubbard 2003, p. 213.

- ↑ Newton & Lumby 2002, p. 37.

Sources

- Hubbard, Edward (1991), The Work of John Douglas, London: The Victorian Society, ISBN 0-901657-16-6

- Newton, Diana; Lumby, Jonathan (2002), The Grosvenors of Eaton, Eccleston, Cheshire: Jennet Publications, ISBN 0-9543379-0-5

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Hubbard, Edward (2003) [1971], Cheshire, The Buildings of England, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-09588-0

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hugh Grosvenor, 1st Duke of Westminster. |

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by the Duke of Westminster

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Lord Robert Grosvenor Sir John Jervis |

Member of Parliament for Chester 1847–1869 With: Sir John Jervis 1847–1850 William Owen Stanley 1850–1857 Enoch Gibbon Salisbury 1857–1859 Philip Stapleton Humberston 1859–1865 William Henry Gladstone 1865–1868 Henry Cecil Raikes 1868–1869 |

Succeeded by Henry Cecil Raikes Norman de L'Aigle Grosvenor |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by The Earl of Bradford |

Master of the Horse 1880–1885 |

Succeeded by The Earl of Bradford |

| Honorary titles | ||

| Preceded by William Tatton Egerton |

Lord Lieutenant of Cheshire 1883–1899 |

Succeeded by The Earl Egerton |

| New office | Lord Lieutenant of the County of London 1889–1899 |

Succeeded by The Duke of Fife |

| Peerage of the United Kingdom | ||

| New creation | Duke of Westminster 1874–1899 |

Succeeded by Hugh Grosvenor |

| Preceded by Richard Grosvenor |

Marquess of Westminster 1869–1899 | |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||