1st Canadian Parachute Battalion

| 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion | |

|---|---|

|

Men of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, about to leave for the D-Day transit camp, England, May 1944. | |

| Active | 1942–1945 |

| Country |

|

| Branch |

|

| Type | Airborne forces |

| Role | Parachute infantry |

| Size | Battalion |

| Part of | British 3rd Parachute Brigade |

| Engagements |

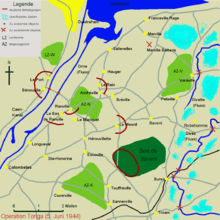

Operation Tonga Battle of the Bulge Operation Varsity |

| Battle honours |

Normandy Landing Dives Crossing The Rhine Northwest Europe 1944–45[1] |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders |

Commanding Officer Designate Major H.D. Proctor, July 1st, 1942-Sept. 7, 1942 Lt. Col. G.F.P. Bradbrooke, 1942–1944 Lt. Col. Jeff Nicklin 1944–1945 |

The 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion was an airborne infantry battalion of the Canadian Army formed in July 1942 during the Second World War; it served in North West Europe. Landing in Normandy during Operation Tonga, shortly before the D-Day landings of 6 June 1944 and in the airborne assault crossing of the River Rhine, Operation Varsity, in March 1945. After the end of hostilities in Europe, the battalion was returned to Canada where it was disbanded on 30 September 1945.

By the end of the war the battalion had gained a remarkable reputation: they never failed to complete a mission, and they never gave up an objective once taken. They are the only Canadians to participate in the Battle of the Bulge and had advanced deeper than any other Canadian unit into enemy territory.[2] Despite being a Canadian Army formation, it was assigned to the British 3rd Parachute Brigade, a British Army formation, which was itself assigned to the British 6th Airborne Division.

Early history

Colonel E.L.M. Burns was the leading mind behind the creation of a Canadian parachute battalion and fought endlessly for its creation.[3] The idea was denied several times because of its lack of relevance in regards to the home army.[2][3] Burns' attempted to suggest that the paratroopers would serve as a good way of transporting troops into obscure parts of Canada if a German attack were to occur.[2][3] It was not until the stunning accomplishments of the German fallschirmjägers, and the creation of British and American parachute regiments, that Canada's military would grant Burns' request.[2][3]

On 1 July 1942 the Department of National Defence authorized the raising of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion. The battalion had an authorised strength of 26 officers and 590 other ranks, formed into a battalion headquarters, three rifle companies and a headquarters company.[4][5] Later in the year, volunteers were also requested for the recently formed 2nd Canadian Parachute Battalion, which formed the Canadian contingent of the 1st Special Service Force.[4]

The initial training was carried out at Fort Benning in the United States and at RAF Ringway in England. Groups of recruits were dispatched to both countries with the intention of getting the best out of both training systems prior to the development of the Canadian Parachute Training Wing at CFB Shilo, Manitoba.[4] The group that traveled to Fort Benning in the United States included the unit's first Commanding Officer, Major H. D. Proctor, who was killed in an accident when his parachute rigging lines were severed by a following aircraft. He was replaced by Lieutenant Colonel G. F. P. Bradbrooke, who led the battalion until the end of operations in Normandy on 14 June 1944.[4]

Recruitment and training

Due to very high standards and an alarming dropout rate, the members of the battalion were the elite of the Canadian Army. The screening process for possible candidates was extreme and further grading systems were put into place to ensure that only the very finest were kept.

A: Outstanding

B: Superior

C: Average

D: Inferior but acceptable

E: Rejected

Only men who fell under the "A" category were kept for airborne training. That was 20% of the original volunteers.[6] The training was separated into four separate stages labelled "A", "B", "C", and "D".

"A" stage consisted of a series of gruelling exercises including Jiu-Jitsu and other hand-to-hand combat classes. Candidates were given the permission to quit at this point. The "A" stage was a way of weeding out men who were unfit to be a paratrooper.[6]

"B" stage saw the highest percentage of dropouts. It consisted of a series of landing exercises and also included "the man breaker" which was a thirty-two foot high structure used to practice plane exit drills.[6]

"C" stage was done using a 250-foot high tower to perform parachuting drills and important life saving techniques.[6]

"D" stage was the final step of the training. Soldiers had to complete five successful jumps from an airborne plane to successfully pass and become a Canadian paratrooper.[6]

England

In July 1943, the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion was dispatched to England and came under the command of the 3rd Parachute Brigade of the British 6th Airborne Division.[4][5] The Battalion then spent the next year in training for airborne operations. Major differences between their previous American training and the new regime included jumping with only one parachute, and doing it through a hole in the floor of the aircraft, instead of through the door of a C-47 Dakota.[4]

Operation Overlord

On the evening on 5 June 1944 the battalion was transported to France in fifty aircraft. Each man carried a knife, toggle rope, escape kit with French currency, and two 24-hour ration packs in addition to their normal equipment, in all totalling 70 pounds. The battalion landed one hour in advance of the rest of the brigade in order to secure the Drop zone (DZ). Thereafter they were ordered to destroy road bridges over the river Dives and its tributaries at Varaville, then neutralize strongpoints at the crossroads.[4][5]

In addition, the Canadians were to protect the left (southern) flank of the 9th Battalion, Parachute Regiment during that unit's attack on the Merville Battery, afterwards seizing a position astride the Le Mesnil crossroads, a vital position at the centre of the ridge.[4][5]

Lieutenant Colonel Bradbrooke issued the following orders to his company commanders:

C Company (Major H.M. MacLeod) was to secure the DZ, destroy the enemy headquarters (HQ), secure the SE corner of the DZ, destroy the radio station at Varaville, and blow the bridge over the Divette stream in Varaville. C Coy would then join the battalion at Le Mesnil cross roads.

A Company (Major D. Wilkins) would protect the left flank of 9th Btn during their attack on the Merville Battery and then cover 9th Battalion's advance to the Le Plein feature. They would seize and hold the Le Mesnil cross roads.

B Company (Major C. Fuller) was to destroy the bridge over the river Dives within two hours of landing and deny the area to the enemy until ordered to withdraw to Le Mesnil cross roads.

The Battalion landed between 0100 and 0130 hours on June 6, becoming the first Canadian unit on the ground in France. For different reasons, including adverse weather conditions and poor visibility, the soldiers were scattered, at times quite far from the planned drop zone. By mid-day, and in spite of German resistance, the men of the battalion had achieved all their objectives; the bridges on the Dives and Divette in Varaville and Robehomme were cut, the left flank of the 9th Parachute Battalion at Merville was secure, and the crossroads at Le Mesnil was taken. In the following days, the Canadians were later involved in ground operations to strengthen the bridgehead and support the advance of Allied troops towards the Seine River.

On 23 August 1944 Lieutenant Colonel Bradbrooke was appointed to the General Staff at Canadian Military Headquarters in London with Major Eadie taking temporary control of the battalion.[4] Three days later, on 26 August 1944, the 6th Airborne Division was pulled from the line in Normandy. Of the 27 officers and 516 men from the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion who took part in the Battle of Normandy, 24 officers and 343 men gave their lives. The unit had to be re-organized and retrained in order to regain its strength and combat-readiness. The Battle of Normandy had brought a major change to the way the war was fought. Airborne troops needed new training to prepare for an offensive role, including street fighting and capturing enemy positions.[4][5] On 6 September the Battalion left Normandy and returned to the Bulford training camp in the United Kingdom.[4][5] While there, Lieutenant Colonel Jeff Nicklin became battalion commander.

In December 1944, the Battalion was again sent to mainland Europe—on Christmas Day they sailed for Belgium, to counter the German offensive in the Ardennes what became known as the Battle of the Bulge.[4][5]

The Ardennes and Holland

On 2 January 1945, the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion was again committed to ground operations on the continent, arriving at the front during the last days of the Battle of the Bulge. They were positioned to patrol during both day and night and defend against any enemy attempts to infiltrate their area. The Battalion also took part in a general advance, taking them through the towns of Aye, Marche, Roy and Bande. The capture of Bande marked the end of the fight for the Bulge and the Battalion's participation in the operation.[4][5]

The Battalion was next moved into the Netherlands in preparation for the crossing of the River Rhine. They were active in carrying out patrols and raids and to establish bridge heads where and when suitable. Despite the heavy shelling of the Canadian positions, there were very few casualties considering the length of time they were there and the strength of the enemy positions.[4] During this time, the Battalion maintained an active defence as well as considerable patrol activity until its return to the United Kingdom on 23 February 1945.

On 7 March 1945, the Battalion returned from leave to start training for what would be the last major airborne operation of the war, Operation Varsity, the crossing of the Rhine.[4][5]

Operation Varsity

The 17th U.S. Airborne and 6th British Airborne divisions were tasked to capture Wesel across the Rhine River, to be completed as a combined paratrooper and glider operation conducted in daylight.[4][5]

3rd Para Brigade was tasked

- To clear the DZ and establish a defensive position road at the west end of the drop zone.

- To seize the Schnappenburg feature astride the main road running north and south of this feature.[4]

1st Canadian Parachute Battalion was ordered to seize and hold the central area on the western edge of the woods, where there was a main road running north from the Wesel to Emmerich, and to a number of houses. It was believed this area was held by German paratroopers. "C" Company would clear the northern part of the woods near the junction of the roads to Rees and Emmerich. Once this area was secure, "A" Company would advance through the position and seize the houses located near the DZ. "B" Company would clear the South-Western part of the woods and secure the battalion's flank.[4] Despite some of the paratroopers being dropped some distance from their landing zone, the Battalion managed to secure its objectives quickly.[4] The battalion lost its commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Jeff Nicklin, who was killed during the initial jump on 24 March 1945. Following the death of Nicklin, the last unit commander was Lt. Col. G.F. Eadie until the Battalion's disbandment.[4]

The outcome of this operation was the defeat of the I. Fallschirmkorps in a day and a half. In the following 37 days, the Battalion advanced 285 miles (459 km) as part of the British 6th Airborne Division, encountering the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp on 15 April 1945 and taking the city of Wismar on 2 May 1945 to prevent the Soviets from advancing too far West.[7][4][5] It was at Wismar that the battalion met up with the Red Army (the only Canadian army unit to do so during hostilities, other than a Canadian Film and Photo Unit detachment). The armistice was signed on 8 May and the battalion returned to England.[4][5]

The Battalion sailed for Canada on the Isle de France on 31 May 1945, and arrived in Halifax on 21 June.[4][5] They were the first unit of the Canadian Army to be repatriated and on September 30 the battalion was officially disbanded.[4][5]

Victoria Cross

One member of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion was awarded the Victoria Cross, Corporal Frederick George Topham,[8][9] east of the River Rhine, near Wesel, Germany, on 24 March 1945.

See also

References

- ↑ Eagle Sgt. "Allied Airborne Headquarters - CANADIAN AIRBORNE". homeusers.brutele.be. Retrieved 2014-07-28.

- 1 2 3 4 Horn, Bernd. Bastard Sons, and Examination of Canada's Airborne Experience 1942–1995. Vanwell Publishing Limited, 2001

- 1 2 3 4 Horn, Bernd. (1999). A Question of Relevance. Canadian Military History. 8, 27–38.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 "89fss".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "junobeach".

- 1 2 3 4 5 Horn, Bernd; Wyczynski, Michel Paras Versus the Reich: Canada's Paratroopers at War, 1942–45. Dundurn publishing, 2003

- ↑ Celinscak, Mark (2015). Distance from the Belsen Heap: Allied Forces and the Liberation of a Concentration Camp. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9781442615700.

- ↑ London Gazette, 3 August 1945

- ↑ Archived Citation from VictoriaCross.org

Further reading

- John A. Willes, Out of the Clouds: The History of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, 1995.

- Dan Hartigan, A Rising of Courage: Canada's Paratroops in the Liberation of Normandy, Calgary, Drop Zone Publishers, 2000.

- Bernd Horn & Michael Wyczynski, Tip of the Spear: An Intimate Account of 1 Canadian Parachute Battalion, Dundurn Press 2002.

- Gary Boegel, Boys of the Clouds: An Oral History of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion 1942–45, Trafford, 2005