1993 Storm of the Century

| Category 5 "Extreme" (RSI: 24.67) | |

| |

| Type |

Superstorm Extratropical cyclone Nor'easter Blizzard |

|---|---|

| Formed | March 12, 1993 |

| Dissipated | March 15, 1993 |

| Lowest pressure | 960 mb (hPa) |

| Lowest temperature | −12 °F (−24 °C) |

| Maximum snowfall or ice accretion |

69 in (180 cm) – Mt. Le Conte, TN |

| Damage | $8.7 billion (2013 US$)[1] |

| Casualties | 208 fatalities |

| Areas affected | Canada, United States, and Cuba |

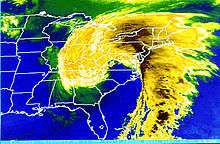

The 1993 Storm of the Century, also known as the '93 Super Storm, the Great Blizzard of 1993, or the No Name Storm, was a large cyclonic storm that formed over the Gulf of Mexico on March 12, 1993. The storm eventually dissipated in the North Atlantic Ocean on March 15, 1993. It was unique for its intensity, massive size, and wide-reaching effects, particularly in the southeastern United States.[2] At its height, the storm stretched from Canada to Central America, but it impacted mainly the eastern United States and Cuba. The cyclone moved through the Gulf of Mexico and then through the eastern United States before moving onto Canada.

Areas as far south as central Alabama and Georgia received 7 to 8 inches (18 to 20 cm) of snow. Areas such as Birmingham, Alabama received up to 12 inches (30 cm) with isolated reports of 16 inches (41 cm). The Florida Panhandle reported up to 4 inches (10 cm),[3] with hurricane-force wind gusts and record low barometric pressures. Between Louisiana and Cuba, the hurricane-force winds produced high storm surges across north-western Florida which, in combination with scattered tornadoes, killed dozens of people.

Record cold temperatures were seen across portions of the south and east of the US in the wake of this storm. In the United States, the storm was responsible for the loss of electric power to more than 10 million households. An estimated 40 percent of the country's population experienced the effects of the storm[4] with a total of 318 fatalities,[5] making it one of the most deadly weather events of the 20th century.

Forecasting

The 1993 Storm of the Century marked a milestone in the weather forecasting of the United States. By March 2, 1993, several operational numerical weather prediction models and medium-range forecasters at the United States National Weather Service recognized the threat of a significant snowstorm. This marked the first time National Weather Service meteorologists were able to predict accurately a system's severity five days in advance. Official blizzard warnings were issued two days before the storm arrived, as shorter-range models began to confirm the predictions. Forecasters were finally confident enough of the computer-forecast models to support decisions by several northeastern states to declare a State of Emergency even before the snow started to fall.[6]

Meteorological history

During March 11 and 12, 1993, temperatures over much of the eastern United States began to drop as an arctic high pressure system built over the Midwest and Great Plains. The extratropical area of low pressure formed in Mexico and moved eastward into the Gulf of Mexico along a stationary front, which developed thunderstorm activity near its center. A strong, short wave trough in the southern branch of the polar jet stream strengthened the surface low pressure area. As the area of low pressure moved through the central Gulf of Mexico, a short wave trough in the northern branch of the jet stream fused with the system in the southern stream, which further strengthened the surface low. A squall line developed along the system's cold front, which moved rapidly across the eastern Gulf of Mexico through Florida and Cuba.[7] The cyclone's center moved into north-west Florida early on the morning of March 13, 1993 with a significant storm surge in the northwestern Florida peninsula that drowned several people.

Barometric pressures recorded during the storm were low. Readings of 976.0 millibars (28.82 inHg) were recorded in Tallahassee, Florida, and even lower readings of 960.0 millibars (28.35 inHg) were observed in New England. Usually such low readings near the coast of the Gulf of Mexico are observed only in hurricanes of category 2 intensity on the Saffir-Simpson hurricane scale[8] or within cyclonic storms at sea. Snow began to spread over the eastern United States, and a large squall line moved from the Gulf of Mexico into Florida and Cuba. The storm system tracked up the East Coast during Saturday and into Canada by early Monday morning. In the storm's wake, unseasonably cold temperatures were recorded over the next day or two in the southeast.

Blizzard impact

This storm complex was massive, affecting at least 26 US states and much of eastern Canada. It brought in cold air along with heavy precipitation and hurricane-intense winds which, ultimately, caused a blizzard over the affected area; this also included thundersnow from Texas to Pennsylvania and widespread whiteout conditions. Snow fell as far south as Jacksonville, Florida,[9] and some areas of Central Florida received several inches of snow,[3] making it the most significant winter storm to affect the state since 1899.[10] Snow mixed in with the rain as temperatures in Tampa, Florida hovered below freezing after the front passed. The storm severely impacted both ground and air travel. Airports were closed all along the eastern seaboard, and flights were cancelled or diverted, thus stranding many passengers along the way. Every airport from Halifax, Nova Scotia, to Tampa, was closed for some time because of the storm. Highways were also closed or restricted all across the affected region, even in states generally well prepared for snow emergencies.

| Snowstorm Totals Totals are for the main system only. | |

|---|---|

| Snowshoe, WV | 44 in (110 cm)[11] |

| Syracuse, NY | 43 in (110 cm)[11] |

| Tobyhanna, PA | 42 in (110 cm)[11] |

| Lincoln, NH | 35 in (89 cm)[11] |

| Boone, NC | 33 in (84 cm) |

| Gatlinburg, TN | 30 in (76 cm)[11] |

| Pittsburgh, PA | 25.2 in (64 cm) |

| Chattanooga, TN | 23 in (58 cm)[11] |

| London, KY | 22 in (56 cm)[12] |

| Worcester, MA | 20.1 in (51 cm)[13] |

| Ottawa, ON | 17.7 in (45 cm)[14] |

| Birmingham, AL | 17 in (43 cm)[11] |

| Montreal, QC | 16.1 in (41 cm)[15] |

| Trenton, NJ | 14.8 in (38 cm) |

| Washington, D.C. (Dulles) | 14.1 in (36 cm) |

| Birmingham, AL | 13 in (33 cm) [16] |

| Boston, MA | 12.8 in (33 cm) |

| New York, NY (LaGuardia) | 12.3 in (31 cm) |

| Baltimore, MD (BWI) | 11.9 in (30 cm) |

| Atlanta, GA (northern suburbs) | 10.0 in (25 cm) |

| Huntsville, AL | 7 in (18 cm) [17] |

| Washington, D.C. (National Airport) | 6.6 in (17 cm) |

| Atlanta, GA (Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport) | 4.5 in (11 cm)[11] |

| Mobile, AL | 3 in (7.6 cm) |

| Tampa, FL | 1 in (2.5 cm) |

Some affected areas in the Appalachian region saw more than 3.6 feet (1.1 m) of snow, and snowdrifts were as high as 35 feet (11 m). The volume of the storm's total snowfall was later computed to be 12.91 cubic miles (53.8 km3), an amount which would weigh (depending on the variable density of snow) between 5.4 and 27 billion tons.

The weight of the record snow falls collapsed several factory roofs in the South; and snowdrifts on the windward sides of buildings caused a few decks with substandard anchors to fall from homes. Though the storm was forecast to strike the snow-prone Appalachian Mountains, hundreds of people were nonetheless rescued from the Appalachians, many caught completely off guard on the Appalachian Trail or in cabins and lodges in remote locales. Snow drifts up to 14 feet (4.3 m) were observed at Mount Mitchell. Snowfall totals of between 2 and 3 feet (0.61 and 0.91 m) were widespread across northwestern North Carolina. Boone, North Carolina—in a high-elevation area accustomed to heavy snowfalls—was nonetheless caught off guard by 36" plus of snow and 24 hours of temperatures below 0 °F (−18 °C) along with storm velocity winds which (according to NCDC storm summaries) gusted as high as 110 miles per hour (180 km/h). Electricity was not restored to many isolated rural areas for up to three weeks, with power cuts occurring all over the east. Nearly 60,000 lightning strikes were recorded as the storm swept over the country for a total of seventy-two hours. As one of the most powerful, complex storms in recent history, this March 1993 storm was described as the "Storm of the Century" by many of the areas affected.

Blizzard impact surrounding the Gulf of Mexico

Gulf of Mexico

The United States Coast Guard dealt with "absolutely incredible, unbelievable" conditions within the Gulf of Mexico. The 200-ft. freighter Fantastico sank 70 miles off of Ft. Myers, Florida during the storm. Seven of its crew died when a Coast Guard helicopter was forced back to base due to low fuel levels after rescuing three of its crew. The 147-ft. freighter Miss Beholding ran aground on a coral reef ten miles from Key West, Florida. Several other smaller vessels sank in the rough seas. In all, the Coast Guard rescued 235 people from over 100 boats across the Gulf of Mexico during the tempest.[18]

Florida

Besides producing record-low barometric pressure across a swath of the southeast and Mid-Atlantic states, and contributing to one of the nation's biggest snowstorms, the low produced a potent squall line ahead of its cold front. The squall line produced a serial derecho as it moved into Florida and Cuba shortly after midnight on March 13. Straight-line winds gusted above 100 mph (87 kn, 160 km/h) at many locations in Florida as the squall line moved through. The supercells in the derecho produced eleven tornadoes. One tornado killed three people when it struck a home which later collapsed, pinning the occupants under a fallen wall.[19] A substantial tree fall was seen statewide from this system.

A substantial storm surge was also generated along the gulf coast from Apalachee Bay in the Florida Panhandle to north of Tampa Bay. Due to the angle of the coast relative to the approaching squall, Taylor County along the eastern portion of Apalachee Bay and Hernando County north of Tampa were especially hard-hit.[3]

Storm surges in those areas reached up to 12 feet (3.7 m), higher than many hurricanes. With little advance warning of incoming severe conditions, some coastal residents were awakened in the early morning of March 13 by the waters of the Gulf of Mexico rushing into their homes.[20] More people died from drowning in this storm than during Hurricane Hugo and Hurricane Andrew combined.[4] Overall, the storm's surge, winds, and tornadoes damaged or destroyed 18,000 homes.[21] A total of 47 lives were lost in Florida due to this storm.[3]

In Florida, this storm was and still is referred to as the "No Name Storm".

Cuba

In Cuba, wind gusts reached 100 miles per hour (160 km/h) in the Havana area. A survey conducted by a research team from the Institute of Meteorology of Cuba suggests that the maximum winds could have been as high as 130 miles per hour (210 km/h). It is the most damaging squall line ever recorded in Cuba.

There was widespread and significant damage in Cuba, with damage estimated as intense as F2.[7] The squall line finally moved out of Cuba near sunrise, leaving 10 deaths and US$1 billion in damage on the island.

Tornadoes spawned by the storm

| F0 | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| F# | Location | County | Time (UTC) | Path length | Fatalities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Florida | ||||||

| F2 | NW of Chiefland | Levy | 0438 | 1 mile (1.6 km) | 3 deaths | |

| F1 | E of Crystal River | Citrus | 0438 | 0.5 miles (0.80 km) | ||

| F0 | St. Petersburg area | Pinellas | 0500 | 0.2 miles (0.32 km) | ||

| F0 | New Port Richey area | Pasco | 0504 | 0.1 miles (0.16 km) | ||

| F2 | Ocala area | Marion | 0520 | 15 miles (24 km) | ||

| F1 | N of LaCrosse | Alachua | 0520 | 0.8 miles (1.3 km) | 1 death | |

| F2 | NW of Howey Height to Alamonte Springs | Lake | 0530 | 30 miles (48 km) | 1 death | |

| F1 | Tampa area | Hillsborough | 0530 | 0.6 miles (0.97 km) | ||

| F1 | Jacksonville area (1st tornado) | Duval | 0600 | 0.8 miles (1.3 km) | ||

| F0 | Bartow area | Polk | 0600 | 0.1 miles (0.16 km) | ||

| F0 | Jacksonville area (2nd tornado) | Duval | 0610 | 0.1 miles (0.16 km) | ||

| Sources:

Tornado History Project Storm Data – March 12, 1993, Tornado History Project Storm Data – March 13, 1993 | ||||||

See also

References

- ↑ Chris Dolce,Jon Erdman,Nick Wiltgen. "Superstorm 1993: 20 Years Ago This Week". Retrieved March 24, 2013.

- ↑ Armstrong, Tim. "Superstorm of 1993: "Storm of the Century"". NOAA. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 National Climatic Data Center (1993). "Event Details". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 22, 2010.

- 1 2 Office of Meteorology (August 24, 2000). "Assessment of the Superstorm of March 1993" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 January 2011. Retrieved December 21, 2010.

- ↑ "Superstorm of 1993". National Weather Service.

- ↑ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (December 14, 2006). "Forecasting the "Storm of the Century"". Retrieved March 14, 2007.

- 1 2 Arnaldo P. Alfonso and Lino R. Naranjo (March 1996). "The 13 March 1993 Severe Squall Line over Western Cuba". Weather and Forecasting (American Meteorological Society) 11: 89–102. Bibcode:1996WtFor..11...89A. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(1996)011<0089:TMSSLO>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0434. Retrieved April 25, 2007.

- ↑ Satellite and Information Service Division (April 17, 2005). "Dvorak Current Intensity Chart". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 17 June 2006. Retrieved June 12, 2006.

- ↑ "History | Weather Underground". Wunderground.com. Retrieved 2012-11-01.

- ↑ T. Frederick Davis (1908). "Climatology of Jacksonville, Fla. and Vicinity" (PDF). United States Weather Bureau. Retrieved January 22, 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Neal Lott (May 14, 1993). "The Big One! A Review of the March 12–14, 1993 "Storm of the Century" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- ↑ David Sander & Glen Conner. "Fact Sheet: Blizzard of 1993". Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- ↑ Mike Carbone, Neal Strauss, Frank Nocera, Dave Henry (March 16, 2001). "Top 10 Record Snowfalls of New England". National Weather Service Forecast Office, Taunton, Massachusetts. Retrieved June 26, 2009.

- ↑ Reuters (March 15, 1993). "Plus de 100 morts de Cuba au Quebec". La Presse. p. A3.

- ↑ Lapointe, Pascal (March 15, 1993). "Le Québec y a goûté !". Le Soleil. p. A1.

- ↑ Gray, Jeremy (March 11, 2013). "Where were you during the Blizzard of '93? AL.com wants your pictures, memories". al.com. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ↑ Wilhelm, Mike (March 11, 2013). "20th Anniversary of Blizzard of 1993". Mike Wilhelm's Alabama Weather Blog. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ↑ John Galvin (December 18, 2009). "Superstorm: Eastern and Central U.S., March 1993". Popular Mechanics (Hearst Communication, Inc.): 1. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- ↑ Storm Prediction Center (August 4, 2004). "Summary of the Subtropical Derecho". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 21, 2010.

- ↑ Rick Gershman (March 18, 1993). "Losing a home, then losing a life". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved December 22, 2010.

- ↑ St. Petersburg Times (1999). "A storm with no name". Retrieved December 22, 2010.