The Last Temptation of Christ (film)

| The Last Temptation of Christ | |

|---|---|

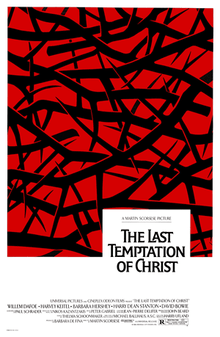

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Martin Scorsese |

| Produced by |

Barbara De Fina Harry Ulfland |

| Screenplay by |

Paul Schrader Uncredited: Martin Scorsese Jay Cocks |

| Based on |

The Last Temptation of Christ by Nikos Kazantzakis |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Peter Gabriel |

| Cinematography | Michael Ballhaus |

| Edited by | Thelma Schoonmaker |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 162 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States[2] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $7 million[3] |

| Box office | $8.8 million[4] |

The Last Temptation of Christ is a 1988 American epic drama film directed by Martin Scorsese. Written by Paul Schrader with uncredited rewrites from Scorsese and Jay Cocks, the film is a film adaptation of Nikos Kazantzakis' controversial 1953 novel of the same name. The film, starring Willem Dafoe, Harvey Keitel, Barbara Hershey, Andre Gregory, Harry Dean Stanton, and David Bowie, was shot entirely in Morocco.

Like the novel, the film depicts the life of Jesus Christ and his struggle with various forms of temptation including fear, doubt, depression, reluctance and lust. This results in the book and film depicting Christ being tempted by imagining himself engaged in sexual activities, a notion that has caused outrage from some Christians. The film includes a disclaimer explaining that it departs from the commonly accepted biblical portrayal of Jesus' life and is not based on the Gospels.

Scorsese received an Academy Award nomination for Best Director, and Hershey's performance as Mary Magdalene earned her a Golden Globe for Best Supporting Actress nomination, while Keitel's performance as Judas earned him a Golden Raspberry Award for Worst Supporting Actor nomination.

Plot

Jesus of Nazareth is a carpenter in Roman-occupied Judea, torn between his own desires and his knowledge that God has a plan for him. His conflict results in self-loathing, and he collaborates with the Romans to crucify Jewish rebels.

Judas Iscariot, a friend of Jesus' originally sent to kill him for collaboration, instead suspects that Jesus is the Messiah and asks him to lead a liberation war against the Romans. Jesus replies that his message is love of mankind; whereupon Judas joins Jesus in his ministry, but threatens to kill him if he strays from the purpose of rebellion. Jesus also has an undisclosed prior relationship with Mary Magdalene, a Jewish prostitute.

After saving Mary Magdalene from a mob gathered to stone her for prostitution and working on the sabbath, Jesus starts preaching. He acquires disciples, but remains uncertain of his role. He visits John the Baptist, who baptizes him, and the two discuss theology and politics. John's primary goal is to gain freedom from the Romans, while Jesus maintains people should tend to matters of the spirit. Jesus then goes into the desert to test God's connection to himself, where he is tempted by Satan, but resists and envisions himself with an axe, being instructed by John the Baptist in answer to Jesus' dilemma of whether to choose the path of love (symbolized by the heart) or the path of violence (represented by the axe). Jesus returns from the desert to the home of Martha and Mary of Bethany, who restore him to health and attempt to persuade him that the way to please God is to have a home, a marriage, and children. Jesus then appears to his waiting disciples to tear out his own heart and invites them to follow him. With newfound confidence he performs various miracles and raises Lazarus from the dead.

Eventually his ministry reaches Jerusalem, where Jesus performs the Cleansing of the Temple and leads a small army to capture the temple by force, but halts on the steps to await a sign from God. He begins bleeding from his hands, which he recognizes as a sign that he must die on the cross to bring salvation to mankind. Confiding in Judas, he persuades the latter to give him to the Romans, despite Judas' inclination otherwise. Jesus convenes his disciples for Passover seder, whereupon Judas leads a contingent of soldiers to arrest Jesus in the garden of Gethsemane. Jesus turns himself over. Pontius Pilate confronts Jesus and tells him that he must be put to death because he represents a threat to the Roman Empire. Jesus is flogged, a crown of thorns is placed on his head and finally he is crucified.

While on the cross, Jesus converses with a young lady who claims to be his guardian angel. She tells him that although he is the Son of God, he is not the Messiah, and that God is pleased with him, and wants him to be happy. She brings him down off the cross and, invisible to others, takes him to Mary Magdalene, whom he marries. They are soon expecting a child and living an idyllic life; but she abruptly dies, and Jesus is consoled by his angel; next he takes Mary and Martha, the sisters of Lazarus, for his wives. He starts a family with them, having many children, and lives his life in peace.

Many years later, Jesus encounters the apostle Paul preaching about the Messiah, telling stories of Jesus's resurrection and ascension to heaven. Jesus tries to tell Paul that he is the man about whom Paul has been preaching, and argues that salvation cannot be founded on lies. But Paul is unmoved, saying that even if his message is not the truth, it is what the world needs to hear, and nothing will stop him from proclaiming it.

Near the end of his life, an elderly Jesus calls his former disciples to his bed. Peter, Nathaniel, and a scarred John visit their master as Jerusalem is in the throes of the Jewish Rebellion against the Romans. Judas comes last and reveals that the youthful angel who released Jesus from the crucifixion is in fact Satan. Crawling back through the burning city of Jerusalem, Jesus reaches the site of his crucifixion and begs God to let him fulfill his purpose and to "let him be God's son."

Jesus then finds himself once more on the cross, having overcome the "last temptation" of escaping death, being married and raising a family, and the ensuing disaster that would have consequently encompassed mankind. Naked and bloody, Jesus cries out in ecstasy as he dies, "It is accomplished!" and the screen flickers to white.

Cast

- Willem Dafoe as Jesus

- Harvey Keitel as Judas Iscariot

- Barbara Hershey as Mary Magdalene

- Harry Dean Stanton as Saul/Paul of Tarsus

- David Bowie as Pontius Pilate

- Steve Shill as Centurion

- Verna Bloom as Mary, mother of Jesus

- Roberts Blossom as Aged Master

- Barry Miller as Jeroboam

- Gary Basaraba as Andrew

- Irvin Kershner as Zebedee

- Victor Argo as Peter

- Paul Herman as Philip

- John Lurie as James

- Michael Been as John

- Leo Burmester as Nathaniel

- Andre Gregory as John the Baptist

- Alan Rosenberg as Thomas

- Nehemiah Persoff as Rabbi

- Peter Berling as Beggar

- Leo Marks as Voice of Satan

- Juliette Caton as Girl Angel

- Martin Scorsese (uncredited) as Isaiah

Production

Scorsese had wanted to make a film version of Jesus' life since childhood. Scorsese optioned the novel The Last Temptation in the late 1970s, and he gave it to Paul Schrader to adapt. The Last Temptation was originally to be Scorsese's follow-up to The King of Comedy; production was slated to begin in 1983 for Paramount, with a budget of about $14 million and shot on location in Israel. The original cast included Aidan Quinn as Jesus, Sting as Pontius Pilate, Ray Davies as Judas Iscariot,[5] and Vanity as Mary Magdalene. Management at Paramount and its parent company, Gulf+Western grew uneasy due to the ballooning budget for the picture and protest letters received from religious groups. The project went into turnaround and was finally canceled in December 1983. Scorsese went on to make After Hours instead.

In 1986, Universal Studios became interested in the project. Scorsese offered to shoot the film in 58 days for $7 million,[3] and Universal greenlit the production. Critic and screenwriter Jay Cocks worked with Scorsese to revise Schrader's script. Aidan Quinn passed on the role of Jesus, and Scorsese recast Willem Dafoe in the part. Sting also passed on the role of Pilate, with the role being recast with David Bowie. Principal photography began in October 1987. The location shoot in Morocco (a first for Scorsese) was difficult, and the difficulties were compounded by the hurried schedule. "We worked in a state of emergency," Scorsese recalled. Scenes had to be improvised and worked out on the set with little deliberation, leading Scorsese to develop a minimalist aesthetic for the film. Shooting wrapped by December 25, 1987.

Music

The film's musical soundtrack, composed by Peter Gabriel, received a Golden Globe Award nomination for Best Original Score - Motion Picture in 1988 and was released on CD with the title Passion, which won a Grammy in 1990 for Best New Age Album. The film's score itself helped to popularize world music. Gabriel subsequently compiled an album called Passion – Sources, including additional material by various musicians that inspired him in composing the soundtrack, or which he sampled for the soundtrack.

Release

The film opened on August 12, 1988.[6] The film was later screened as a part of the Venice International Film Festival on September 7, 1988.[7] In response to the film's acceptance as a part of the film festival's lineup, director Franco Zeffirelli removed his film Young Toscanini from the program.[8]

Attack on Saint Michel theatre, Paris

On October 22, 1988, an integrist Catholic group set fire to the Parisian Saint Michel theatre while it was showing the film. A little after midnight, an incendiary device ignited under a seat in the less supervised underground room, where a different film was being shown. The incendiary device consisted of a charge of potassium chlorate, triggered by a vial containing sulphuric acid.[9]

The attack injured thirteen people, four of whom were severely burned.[10][11] The Saint Michel theatre was heavily damaged,[11] and reopened three years later after restoration. The Archbishop of Paris, Jean-Marie Cardinal Lustiger, had previously condemned the film without having seen it, but also condemned the attack, calling the perpetrators "enemies of Christ".[11]

The attack was subsequently blamed on a Christian fundamentalist group linked to Bernard Antony, a representative of the far-right Front National to the European Parliament in Strasbourg, and the excommunicated followers of Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre.[10] Similar attacks against theatres included graffiti, setting off tear-gas canisters and stink bombs, and assaulting filmgoers.[10] At least nine people believed to be members of the Christian fundamentalist group were arrested.[10] Five militants of a group called "General Alliance Against Racism and for Respect of the French and Christian Identity" (Alliance générale contre le racisme et pour le respect de l'identité française et chrétienne) were given suspended prison sentences of between 15 and 36 months, as well as a 450,000 franc fine for damages.[12]

Rene Remond, a historian, said of the Christian far-right, "It is the toughest component of the National Front and it is motivated more by religion than by politics. It has a coherent political philosophy that has not changed for 200 years: it is the rejection of the revolution, of the republic and of modernism."[10]

Controversy

The Last Temptation of Christ's eponymous final sequence depicts the crucified Jesus—tempted by what turns out to be Satan in the form of a beautiful, androgynous child—experiencing a dream or alternative reality where he comes down from the cross, marries Mary Magdalene (and later Mary and Martha), and lives out his life as a full mortal man. He learns on his deathbed that he was deceived by Satan and begs God to let him "be [God's] son," at which point he finds himself once again on the cross. At other points in the film, Jesus is depicted as building crosses for the Romans, being tormented by the voice of God, and lamenting the many sins he believes he has committed.

Because of these departures from the gospel narratives—and especially a brief scene wherein Jesus and Mary Magdalene consummate their marriage—several Christian groups organized vocal protests and boycotts of the film prior to and upon its release. One protest, organized by a religious Californian radio station, gathered 600 protesters to picket the headquarters of Universal Studios' parent company MCA;[13] one of the protestors dressed as MCA's Chairman Lew Wasserman and pretended to drive nails through Jesus' hands into a wooden cross.[6] Evangelist Bill Bright offered to buy the film's negative from Universal in order to destroy it.[13][14] The protests were effective in convincing several theater chains not to screen the film;[13] one of those chains, General Cinemas, later apologized to Scorsese for doing so.[6]

In some countries, including Greece, Turkey, Mexico, Chile, and Argentina, the film was banned or censored for several years. As of July 2010, the film continues to be banned in the Philippines and Singapore.[15]

Home media

Although Last Temptation was released on VHS and Laserdisc, many video rental stores, including the then-dominant Blockbuster Video, declined to carry it for rental as a result of the film's controversial reception.[16] In 1997, the Criterion Collection issued a special edition of Last Temptation on Laserdisc, which Criterion re-issued on DVD in 2000 and on Blu-ray disc in Region A in March 2012.[17]

Reception

Box office

The Last Temptation of Christ opened in 123 theaters on August 12, 1988 and grossed $401,211 in its opening weekend. At the end of its run, it had grossed $8,373,585 domestically and $487,867 in Mexico for a worldwide total of $8,861,452.[4]

Critical response

The film has been positively supported by film critics and some religious leaders. Review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes reports that 82% of 51 film critics have given the film a positive review, with a rating average of 7.4 out of 10.[18] Metacritic, which assigns a weighted average score out of 100 to reviews from mainstream critics, gives the film a score of 80 based on 18 reviews.[19]

In his review of the film, Roger Ebert, who gave the film four out of four stars, writes that Scorsese and screenwriter Paul Schrader "paid Christ the compliment of taking him and his message seriously, and they have made a film that does not turn him into a garish, emasculated image from a religious postcard. Here he is flesh and blood, struggling, questioning, asking himself and his father which is the right way, and finally, after great suffering, earning the right to say, on the cross, 'It is accomplished.'"[20] Ebert later included the film in his list of "Great Movies".[21]

Writers at NNDB claim that "Paul Schrader's screenplay and Willem Dafoe's performance made perhaps the most honestly Christ-like portrayal of Jesus ever filmed."[22]

Christian film critic Steven D. Greydanus has condemned the film, writing, "Poisonous morally and spiritually, it is also worthless as art or entertainment, at least on any theory of art as an object of appreciation. As an artifact of technical achievement, it may be well made; but as a film, it is devoid of redeeming merit."[23] A review associated with Catholic News Service claims that Last Temptation "fails because of artistic inadequacy rather than anti-religious bias."[24]

References

- ↑ "THE LAST TEMPTATION OF CHRIST (18)". British Board of Film Classification. September 2, 1988. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- ↑ http://www.tcm.com/tcmdb/title/80944/Last-Temptation-of-Christ-The/

- 1 2 "Last Temptation Turns Twenty-Five". Christianity Today. August 7, 2013. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- 1 2 "The Last Temptation of Christ (1988)". Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- ↑ Revealed in an interview with Mark Lawson on Front Row, BBC Radio 4, September 23, 2008.

- 1 2 3 Kelly, M. (1991). Martin Scorsese: A Journey. New York, Thunder's Mouth Press.

- ↑ "Venice Festival Screens Scorsese's 'Last Temptation'". Los Angeles Times. September 9, 1988. Retrieved December 9, 2012.

- ↑ "Zeffirelli Protests 'Temptation of Christ'". The New York Times. August 3, 1988. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ↑ Caviglioli, François (15 April 1990). "Le bûcher de Saint-Michel" (PDF). Le Nouvel Observateur. p. 110.

- 1 2 3 4 5 James M. Markham (1988-11-09). "Religious War Ignites Anew in France". New York Times.

- 1 2 3 Steven Greenhouse (1988-10-25). "Police Suspect Arson In Fire at Paris Theater". New York Times.

- ↑ "L'Absolution des terroristes". L'Humanité. 4 April 1990. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 WGBH. "Culture Shock Flashpoints: Martin Scorsese's The Last Temptation of Christ". Public Broadcasting Systems. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ↑ http://articles.latimes.com/1988-07-22/local/me-7602_1_universal-pictures

- ↑ Certification page at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Martin Scorsese et al. (1997). The Last Temptation of Christ [audio commentary] (Laserdisc/DVD/Blu-ray Disc). New York: The Criterion Collection.

- ↑ Katz, Josh (December 15, 2011). "Criterion Blu-ray in March: Scorsese, Kalatozov, Hegedus & Pennebaker, Baker, Lean (Updated)". Blu-ray.com. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- ↑ "The Last Temptation of Christ". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- ↑ "The Last Temptation of Christ". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (7 January 1998). "The Last Temptation of Christ". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ↑ Great Movies Roger Ebert

- ↑ Martin Scorsese Biography

- ↑ "The Last Temptation of Christ: An Essay in Film Criticism and Faith". Decentfilms.com. Retrieved 2013-06-10.

- ↑ "USCCB - (Film and Broadcasting) - Last Temptation of Christ, The". Old.usccb.org. Retrieved 2013-06-10.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Last Temptation of Christ (film) |

- The Last Temptation of Christ at the Internet Movie Database

- The Last Temptation of Christ at Box Office Mojo

- The Last Temptation of Christ at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Last Temptation of Christ at Metacritic

- "Criterion Collection Essay". Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- Pictures of opening day protests against "Last Temptation of Christ" at Wide Angle/Closeup

- "Identity and Ethnicity in Peter Gabriel’s Sound Track for The Last Temptation of Christ'' by Eftychia Papanikolaou; chapter in Scandalizing Jesus?: Kazantzakis’s 'The Last Temptation of Christ' Fifty Years On, edited by Darren J. N. Middleton, with a contribution by Martin Scorsese, 217-228. New York and London: Continuum, 2005.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||