1983–85 famine in Ethiopia

A widespread famine affected the inhabitants of today's Eritrea and Ethiopia from 1983 to 1985.[1] The worst famine to hit the country in a century,[2] in northern Ethiopia it led to more than 400,000 deaths,[3] but more than half this mortality can be attributed to human rights abuses that caused the famine to come earlier, strike harder, and extend further than would otherwise have been the case.[3] Other areas of Ethiopia experienced famine for similar reasons, resulting in tens of thousands of additional deaths.[3] The tragedy as a whole took place within the context of more than two decades of insurgency and civil war.[4]

The famine of 1983–85 is often ascribed to drought. While climatic causes and consequences certainly played a part in the tragedy, it has been suggested that widespread drought occurred only some months after the famine was under way.[5] The famines that struck Ethiopia between 1961 and 1985, and in particular the one of 1983–5, were in large part created by government policies, specifically the set of counter-insurgency strategies employed and so-called "social transformation" in non-insurgent areas.[6][7]

Background

Before the 1983–5 famine, two decades of wars of national liberation and other anti-government conflict had raged throughout Ethiopia and Eritrea. The most prominent feature of the fighting was the use of indiscriminate violence against civilians by the Ethiopian army and air force.[10] Excluding those killed by famine and resettlement, more than 150,000 people were killed.[10]

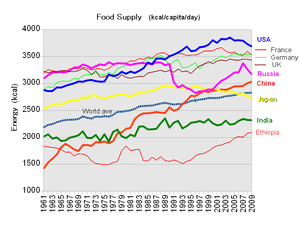

The economy of Ethiopia is based on agriculture: almost half of GDP, 60% of exports, and 80% of total employment come from agriculture.[11]

In 1973, a famine in Wollo killed an estimated 40,000 to 80,000, mostly of the marginalized Afar herders and Oromo tenant farmers, who suffered from the widespread confiscation of land by the wealthy classes and government of Emperor Haile Selassie. Despite attempts to suppress news of this famine, leaked reports contributed to the undermining of the government's legitimacy and served as a rallying point for dissidents, who complained that the wealthy classes and the Ethiopian government had ignored both the famine and the people who had died.[12] Then in 1974, a group of Marxist soldiers known as the Derg overthrew Haile Selassie. The Derg addressed the Wollo famine by creating the Relief and Rehabilitation Commission (RRC) to examine the causes of the famine and prevent its recurrence, and then abolishing feudal tenure on March 1975. The RRC initially enjoyed more independence from the Derg than any other ministry, largely due to its close ties to foreign donors and the quality of some its senior staff. As a result, insurgencies began to spread into the countries administrative regions.[13]

By late 1976 insurgencies existed in all of the country's fourteen administrative regions.[14] The Red Terror (1977–1978) marked the beginning of a steady deterioration in the economic state of the nation, coupled with extractive policies targeting rural areas. The reforms of 1975 were revoked and the Agricultural Marketing Corporation (AMC) was tasked with extracting food from rural peasantry at low rates to placate the urban populations. The very low fixed price of grain served as a disincentive to production, and some peasants had to buy grain on the open market in order to meet their AMC quota. Citizens in Wollo, which continued to be stricken with drought, were required to provide a "famine relief tax" to the AMC until 1984. The Derg also imposed a system of travel permits to restrict peasants from engaging in non-agricultural activities, such as petty trading and migrant labor, a major form of income supplementation. However, the collapse of the system of State Farms, a large employer of seasonal laborers, resulted in an estimated 500,000 farmers in northern Ethiopia losing a component of their income. Grain wholesaling was declared illegal in much of the country, resulting in the number of grain dealers falling from between 20,000 to 30,000 to 4,942 in the decade after the revolution.[15]

The nature of the RRC changed as the government became increasingly authoritarian. Immediately after its creation its experienced core of technocrats produced highly regarded analyses of Ethiopian famine and ably carried out famine relief efforts. However, by the 1980s the Derg had compromised its mission. The RRC began with the innocuous scheme of creating village workforces from the unemployed in state farms and government agricultural schemes but, as the counter-insurgency intensified, the RRC was given responsibility for a program of forced resettlement and villagization. As the go-between for international aid organizations and foreign donor governments, the RRC redirected food to government militias, in particular in Eritrea and Tigray. It also encouraged international agencies to set up relief programs in regions with surplus grain production, which allowed the AMC to collect the excess food. Finally, the RRC carried out a disinformation campaign during the 1980s famine, in which it portrayed the famine as being solely the result of drought and overpopulation and tried to deny the existence of the armed conflict that was occurring precisely in the famine-affected regions. The RRC also claimed that the aid being given by it and its international agency partners were reaching all of the famine victims.[16]

Famine

Five Ethiopian provinces—Gojjam, Eritrea, Hararghe, Tigray, and Wollo—all received record low rainfalls in the mid-1980s.[17] In the south, a separate and simultaneous cause was the government's response to Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) insurgency. In 1984, President Mengistu Haile Mariam announced that 46% of the Ethiopian Gross National Product would be allocated to military spending, creating the largest standing army in sub-Saharan Africa; the allocation for health in the government budget fell from 6% in 1973–4 to 3% by 1990–1.[18]

Although a UN estimate of one million deaths is often quoted for the 1983–5 famine, this figure has been challenged by famine scholar Alex de Waal. In a major study, de Waal criticized the United Nations for being "remarkably cavalier" about the numbers of people who died, with the UN's one-million figure having "absolutely no scientific basis whatsoever," a fact which represents "a trivialization and dehumanization of human misery.".[19] De Waal estimates that 400,000 to 500,000 died in the famine.[20]

Nevertheless, the magnitude of the disaster has been well documented: in addition to hundreds of thousands of deaths, millions were made destitute.[21] Media activity in the West, along with the size of the crisis, led to the "Do They Know It's Christmas?" charity single and the July 1985 concert Live Aid, which elevated the international profile of the famine and helped secure international aid. In the early to mid-1980s there were famines in two distinct regions of the country, resulting in several studies of one famine that try to extrapolate to the other or less cautious writers referring to a single widespread famine. The famine in the southeast of the country was brought about by the Derg's counterinsurgency efforts against the OLF. However, most media referring to "the Ethiopian famine" of the 1980s refers to the severe famine in 1983-5 centered on Tigray and northern Wollo, which further affected Eritrea, Begemder and northern Shewa.[22] Living standards had been declining in these government-held regions since 1977, a "direct consequence" of Derg agricultural policies.[23] A further major contributing factor to the famine were the Ethiopian government's enforced resettlement programs, utilized as part of its counter-insurgency campaign.

| E. Tigray | N. Wollo | N. Begemder | |

|---|---|---|---|

| November/December 1981 | 100 | 50 | 40 |

| November/December 1982 | 165 | 65 | 55 |

| November/December 1983 | 225 | 90 | 45 |

| November/December 1984 | 300 | 160 | 70 |

| June/July 1985 | 380 | 235 | 165 |

Despite RRC claims to have predicted the famine, there was little data as late as early 1984 indicating an unusually severe food shortage. Following two major droughts in the late 1970s, 1980 and 1981 were rated by the RRC as "normal" and "above normal". The 1982 harvest was the largest ever, with the exception of central and eastern Tigray. RRC estimates for people "at risk" of famine rose to 3.9 million in 1983 from 2.8 million in 1982, which was less than the 1981 estimate of 4.5 million. In February and March 1983, the first signs of famine were recognized as poverty-stricken farmers began to appear at feeding centers, prompting international aid agencies to appeal for aid and the RRC to revise its famine assessment. The harvest after the main (meher) harvest in 1983 was the third largest on record, with the only serious shortfall again being recorded in Tigray. In response, grain prices in the two northern regions of Begemder and Gojjam fell. However, famine recurred in Tigray. The RRC claimed in May 1984 that the failure of the short rains (belg) constituted a catastrophic drought, while neglecting to state that the belg crops form a fourth of crop yields where the belg falls, but none at all in the majority of Tigray. A quantitative measure of the famine are grain prices, which show high prices in eastern and central Tigray, spreading outward after the 1984 crop failure.[25]

A major drain on Ethiopia's economy was the ongoing civil war, which pitched rebel movements against the Soviet and Cuban backed Derg government. This crippled the country's economy further and contributed to the governments lack of ability to handle the crisis to come.

By mid-1984 it was evident that another drought and resulting famine of major proportions had begun to affect large parts of northern Ethiopia. Just as evident was the government's inability to provide relief. The almost total failure of crops in the north was compounded by fighting in and around Eritrea, which hindered the passage of relief supplies. Although international relief organizations made a major effort to provide food to the affected areas, the persistence of drought and poor security conditions in the north resulted in continuing need as well as hazards for famine relief workers. In late 1985, another year of drought was forecast, and by early 1986 the famine had spread to parts of the southern highlands, with an estimated 5.8 million people dependent on relief food. In 1986, locust plagues exacerbated the problem.

Response to the famine

Despite the fact that the government had access to only a minority of the famine-stricken population in the north, the great majority of relief was channelled through the government side, prolonging the war.[3]

The Ethiopian government's inability or unwillingness to deal with the 1984-85 famine provoked universal condemnation by the international community. Even many supporters of the Ethiopian regime opposed its policy of withholding food shipments to rebel areas. The combined effects of famine and internal war had by then put the nation's economy into a state of collapse.

The primary government response to the drought and famine was the decision to uproot large numbers of peasants who lived in the affected areas in the north and to resettle them in the southern part of the country. In 1985 and 1986, about 600,000 people were moved, many forcibly, from their home villages and farms by the military and transported to various regions in the south. Many peasants fled rather than allow themselves to be resettled; many of those who were resettled sought later to return to their native regions. Several human rights organizations claimed that tens of thousands of peasants died as a result of forced resettlement.

Another government plan involved villagization, which was a response not only to the famine but also to the poor security situation. Beginning in 1985, peasants were forced to move their homesteads into planned villages, which were clustered around water, schools, medical services, and utility supply points to facilitate distribution of those services. Many peasants fled rather than acquiesce in relocation, which in general proved highly unpopular. Additionally, the government in most cases failed to provide the promised services. Far from benefiting agricultural productivity, the program caused a decline in food production. Although temporarily suspended in 1986, villagization was subsequently resumed.

International view

Close to 8 million people became famine victims during the drought of 1984, and over 1 million died. In the same year (October 23),[26][27] a BBC news crew was the first to document the famine, with Michael Buerk describing "a biblical famine in the 20th Century" and "the closest thing to hell on Earth".[28] The report shocked Britain, motivating its citizens to bring world attention to the crisis in Ethiopia.

In January 1985 the RAF carried out the first airdrops from Hercules C-130s delivering food to the starving people. Other countries including Sweden,[29] East and West Germany, Poland, Canada, USA and the Soviet Union were also involved in the international response.

Charity

Buerk's news piece was seen by Irish singer Bob Geldof, who quickly organised the charity supergroup Band Aid. Their single, "Do They Know It's Christmas?", was released on 3 December 1984 and became Britain's best-selling single within a few weeks, eventually selling 3.69 million copies domestically. All proceeds from the single, apart from value-added tax, went to charities working to relieve the famine. Other charity singles soon followed; "We Are the World" by USA for Africa was the most successful of these, selling 20 million copies worldwide.

Live Aid, a 1985 fund-raising effort headed by Geldof, induced millions of people in the West to donate money and to urge their governments to participate in the relief effort in Ethiopia. Some of the proceeds also went to the famine hit areas of Eritrea.[30] The event raised £145 million.[31]

Effect on aid policy

The manner in which international aid was routed through the RRC gave rise to criticism that forever changed the way in which governments and NGOs respond to international emergencies taking place within conflict situations.[1] International aid supplied to the government and to relief agencies working alongside the government became part of the counter-insurgency strategy of the government. It therefore met real and immediate need, but also prolonged the life of Mengistu's government.[1] The response to the emergency raised disturbing questions about the relationship between humanitarian agencies and host governments.[1]

Aid money and rebel groups

On 3 March 2010, Martin Plaut of the BBC published evidence that millions of dollars worth of aid to the Ethiopian famine were spent in buying weapons by the Tigrayan People's Liberation Front, a communist group trying to overthrow the Ethiopian government at the time. Rebel soldiers said they posed as merchants as "a trick for the NGOs". The report also cited a CIA document saying aid was "almost certainly being diverted for military purposes". One rebel leader estimated $95 million (£63 million).[32] Plaut also said that other NGOs were under the influence or control of the Derg military junta. Some journalists suggested that the Derg was able to use Live Aid and Oxfam money to fund its enforced resettlement and "villagification" programmes, under which at least 3 million people are said to have been displaced and between 50,000 and 100,000 killed.[33] These reports were later refuted by the Band Aid Trust[34] and after a seven-month investigation,[35] the BBC found its reporting had been misleading regarding Band Aid's money and had also contained numerous errors of fact and misstatements of evidence:[34]

Following a complaint from the Band Aid Trust the BBC's Editorial Complaints Unit found in its ruling that that there was no evidence to support such statements and that "they should not have been broadcast". It also added that "The BBC wishes to apologise unreservedly to the Band Aid Trust for the misleading and unfair impression which was created".[34][36]

See also

- Birhan Woldu

- Economy of Ethiopia

- Famines in Ethiopia

- List of famines

- Tears Are Not Enough

- 2010 Sahel famine

- Sahel drought

- 2006 Horn of Africa food crisis

- Malawian food crisis

- 2011 East Africa drought

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 de Waal 1991, p. 2.

- ↑ Gebru 2009, p. 20.

- 1 2 3 4 de Waal 1991, p. 5.

- ↑ de Waal 1991, p. 1.

- ↑ de Waal 1991, p. 4.

- ↑ de Waal 1991, p. 4–6.

- ↑ Young 2006, p. 132.

- ↑ FAO FAOSTAT

- ↑ FAO Food Security

- 1 2 de Waal 1991, p. 3.

- ↑ Ethiopia: Economy, CIA World Factbook, 2009

- ↑ "Feeding on Ethiopia's famine". The Independent.

- ↑ de Waal 2002, pp. 106–9.

- ↑ Ofcansky & LaVerle 1993, p. 43.

- ↑ de Waal 2002, pp. 110–1.

- ↑ de Waal 2002, pp. 111–2.

- ↑ Webb & von Braun 1994, p. 25.

- ↑ Webb & von Braun 1994, p. 35.

- ↑ de Waal 1991, p. iv.

- ↑ http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/Ethiopia919.pdf (pg. 172)

- ↑ Webb & von Braun 1994, p. 29.

- ↑ de Waal 1991.

- ↑ Clay & Holcomb 1986, p. 189–90.

- ↑ de Waal 2002, p. 115.

- ↑ de Waal 2002, p. 113–4.

- ↑ Harvey, Oliver (24 October 2009). "Band Aid saved me but 25 years later my country is still hungry". The Sun (London). Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ↑ "1984: Extent of Ethiopia famine revealed (Video)". BBC News. 22 October 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ↑ Dowden, Richard (17 March 2010). "'Get real, Bob - buying guns might have been better than buying food': After Geldof's angry outburst, an expert on Africa hits back". Mail Online (London). Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ↑ Horisont 1984 (in Swedish). Bertmarks. 1984.

- ↑ "In 1984 Eritrea was part of Ethiopia, where some of the song's proceeds were spent". Archived from the original on 2009-05-11. Retrieved 2009-05-08.

- ↑ James Montgomery: A Look Back At Live Aid, By The Numbers; MTV,com, 2010 (retrieved 19 July 2015)

- ↑ Plaut, Martin. March 3, 2010, BBC World Service, "Ethiopia famine aid 'spent on weapons'". The CIA report is available on the CIA's Freedom of Information Act website, http://www.foia.cia.gov , search for Ethiopia and browse to the 1984/1985 section for the document entitled Ethiopia: Security and Political Impact of the Drought

- ↑ David Rieff (24 June 2005). "Cruel to be kind?". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- 1 2 3 "ECU Ruling: Claims that aid intended for famine relief in Ethiopia had been diverted to buy arms". BBC. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ↑ "News & latest headlines from AOL". AOL.com.

- ↑ "BBC apologises over Band Aid money reports".

References

- Abebe Zegeye; Pausewang, Siegfried (1994). Ethiopia in Change: Peasantry, Nationalism and Democracy. London: British Academic Press. ISBN 1-85043-644-4.

- Andargachew Tiruneh (1993). The Ethiopian Revolution, 1974–1987: A Transformation from an Aristocratic to a Totalitarian Autocracy. Cambridge: University Press. ISBN 0-521-43082-8.

- Clay, Jason; Holcomb, Bonnie (1986). Politics and the Ethiopian Famine 1984–1985. New Brunswick and Oxford: Transaction Books. ISBN 0-939521-34-2.

- Finn, James (1990). Ethiopia: The Politics of Famine. New York, NY: Freedom House. ISBN 0-932088-47-3.

- Gebru Tareke (2009). The Ethiopian Revolution: War in the Horn of Africa. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-14163-4.

- Gill, Peter (2010). Famine and Foreigners: Ethiopia since Live Aid. Oxford: University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-956984-7.

- Johns, Michael (1988). "Gorbachev's Holocaust: Soviet Complicity in Ethiopia's Famine", Policy Review, Summer 1988.

- Kissi, Edward (2006). Revolution and Genocide in Ethiopia and Cambodia. Oxford: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-1263-2.

- Ofcansky, Thomas P; Berry, LaVerle (1993). Ethiopia: A Country Study. Library of Congress Country Studies (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. ISBN 0-8444-0739-9.

- Pankhurst, Alula (1992). Resettlement and Famine in Ethiopia: The Villagers' Experience. Manchester: University Press. ISBN 0-7190-3537-6.

- de Waal, Alex (1991). Evil Days: Thirty Years of War and Famine in Ethiopia. New York & London: Human Rights Watch. ISBN 1-56432-038-3.

- de Waal, Alex (2002) [1997]. Famine Crimes: Politics & the Disaster Relief Industry in Africa. Oxford: James Currey. ISBN 0-85255-810-4.

- Webb, Patrick; von Braun, Joachim; Yohannes, Yisehac (1992). Famine in Ethiopia: Policy Implications of Coping Failure at National and Household Levels. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute. ISBN 0-89629-095-6.

- Webb, Patrick; von Braun, Joachim (1994). Famine and Food Security in Ethiopia: Lessons for Africa. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons.

- Young, John (2006) [1997]. Peasant Revolution in Ethiopia: The Tigray People's Liberation Front, 1975–1991. Cambridge: University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-02606-2.

External links

- The first Canadian TV report by Brian Stewart, produced by Tony Burman, which inspired famine aid projects around the world (1 November 1984)

- 2002 news story from the Australian Broadcasting Corporation

- Flashback 1984: Portrait of a famine

- Thoughts and photos from Brian Stewart, the first Western journalist to cover the story

- CBC News Indepth: Ethiopia