1981 South Africa rugby union tour

The 1981 South African rugby tour (known in New Zealand as the Springbok Tour, and in South Africa as the Rebel Tour) polarised opinions and inspired widespread protests across New Zealand. The controversy also extended to the United States, where the South African rugby team continued their tour after departing New Zealand.[1][2]

Apartheid had made South Africa an international pariah, and other countries were strongly discouraged from having sporting contacts with it. Rugby union was (and is) an extremely popular sport in New Zealand, and the South African team known as the Springboks were considered to be New Zealand's most formidable opponents.[3] Therefore, there was a major split in opinion in New Zealand as to whether politics should influence sport in this way and whether the Springboks should be allowed to tour.

Despite the controversy, the New Zealand Rugby Union decided to proceed with the tour. The government of Prime Minister Robert Muldoon was called on to ban it, but decided that commitments under the Gleneagles Agreement did not require the government to prevent the tour, and decided not to interfere due to their public position of "no politics in sport". Major protests ensued, aiming to make clear many New Zealanders' opposition to apartheid and, if possible, to stop the matches' taking place. This was successful at two games, but also had the effect of creating a law and order issue: whether a group of protesters could be allowed to prevent a lawful game taking place.

The dispute was similar to that involving Peter Hain in the United Kingdom in the early 1970s, when Hain's Stop the Tour campaign clashed with the more conservative 'Freedom Under Law' movement championed by barrister Francis Bennion. The allegedly excessive police response to the protests also became a focus of controversy. Although the protests were among the most intense in New Zealand's recent history, no deaths or serious injuries resulted.

After the tour, no official sporting contact took place between New Zealand and South Africa until the early 1990s, after apartheid had been abolished. The tour has been said to have led to a decline in the popularity of Rugby Union in New Zealand, until the 1987 Rugby World Cup.

Background

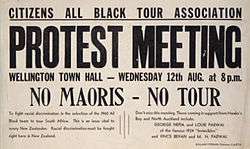

The Springboks and New Zealand's national rugby team, the All Blacks, have a long tradition of intense and friendly sporting rivalry.[4] From the 1940s to the 1960s, the South African apartheid had an impact on team selection for the All Blacks: the selectors passed over Māori players for some All Black tours to South Africa.[5] Opposition to sending race-based teams to South Africa grew throughout the 1950s and 60s. Prior to the All Blacks' tour of South Africa in 1960, 150,000 New Zealanders signed a petition supporting a policy of "No Maoris, No Tour".[5] The tour still happened, and in 1969 Halt All Racist Tours (HART) was formed.[6]

During the 1970s public protests and political pressure forced on the New Zealand Rugby Union (NZRFU) the choice of either fielding a team not selected by race, or not touring South Africa:[5] South African rugby authorities continued to select Springbok players by race.[4] As a result, the Norman Kirk Labour Government prevented the Springboks from touring during 1973.[6] In response, the NZRFU protested about the involvement of "politics in sport".

In 1976 the All Blacks toured South Africa with the blessing of the newly elected New Zealand Prime Minister, Robert Muldoon.[7] Twenty-five African nations protested against this by boycotting the 1976 Summer Olympics in Montreal.[8] In their view the All Black tour gave tacit support to the apartheid regime in South Africa. The 1976 tour contributed to the creation of the Gleneagles Agreement adopted by the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in 1977.[9]

Tour of New Zealand

By the early 1980s the pressure from other countries and from protest groups in New Zealand such as HART reached a head when the NZRU proposed a Springbok tour for 1981. This became a topic of political contention due to the international sports boycott. The Australian Prime Minister, Malcolm Fraser, refused permission for the Springboks' aircraft to refuel in Australia,[10] so the Springboks' flights to and from New Zealand went via Los Angeles and Hawaii.[11]

Despite pressure for the Muldoon government to cancel the tour, permission was granted, and the Springboks arrived in New Zealand on 19 July 1981. Since 1977 Muldoon's government had been a party to the Gleneagles Agreement, in which the countries of the Commonwealth accepted that it was:

- "the urgent duty of each of their Governments vigorously to combat the evil of apartheid by withholding any form of support for, and by taking every practical step to discourage contact or competition by their nationals with sporting organisations, teams or sportsmen from South Africa or from any other country where sports are organised on the basis of race, colour or ethnic origin."

Despite this, Muldoon argued that New Zealand was a free and democratic country, and that "politics should stay out of sport."

Some rugby supporters echoed the separation of politics and sport.[12][13] Others argued that if the tour were cancelled, there would be no reporting of the widespread criticism of apartheid in New Zealand in the controlled South African media. Muldoon's critics felt that he allowed the tour in order for his National Party to secure the votes of rural and provincial conservatives in the general election later in the year, which Muldoon won.[14]

The ensuing public protests polarised New Zealand.[14] While rugby fans filled the football grounds, protest crowds filled the surrounding streets, and on one occasion succeeded in invading the pitch and stopping the game.[15]

To begin with the anti-tour movement was committed to non-violent civil disobedience, demonstrations and direct action. As protection for the Springboks, the police created two special riot squads, the Red and Blue Squads.[16][17] These police were, controversially, the first in New Zealand to be issued with visored riot helmets and long batons (more commonly the side-handle baton). Some protesters were intimidated and interpreted this initial police response as overkill and heavy-handed tactics. After early disruptions, police began to require that all spectators assemble in sports grounds at least an hour before kick-off.

At Gisborne on 22 July,[18] protesters managed to break through a fence, but quick action by spectators and ground security prevented the game being disrupted. Some protesters were injured by police batons.

Hamilton: Game cancelled

At Rugby Park, Hamilton (the site of today's Waikato Stadium), on 25 July,[18] about 350 protesters invaded the pitch after pulling down a fence. The police arrested about 50 of them over a period of an hour, but were concerned that they could not control the rugby crowd, who were throwing bottles and other objects at the protesters.[19] Following reports that a stolen light plane (piloted by Pat McQuarrie)[20] was approaching the stadium, police cancelled the match.[19] The protesters were ushered from the ground and were advised by protest marshals to remove any anti-tour insignia from their attire, with enraged rugby spectators lashing out at them. Gangs of rugby supporters waited outside Hamilton police station for arrested protesters to be processed and released, and assaulted some protesters making their way into Victoria Street.[21]

Wellington: Molesworth Street protest

The aftermath of the Hamilton game, followed by the bloody batoning of marchers in Wellington's Molesworth Street in the following week, in which police batoned bare-headed protesters, led to the radicalisation of the protest movement. Because of this, many protesters began to wear motorcycle or bicycle helmets to protect themselves from batons and head injury.[22][23]

The authorities strengthened security at public facilities after protesters disrupted telecommunications by damaging a waveguide on a microwave repeater, disrupting telephone and data services, though TV transmissions continued as they were carried by a separate waveguide on the tower.[24] Army engineers were deployed, and the remaining grounds were surrounded with razor wire and shipping container barricades to decrease the chances of another pitch invasion. At Eden Park, an emergency escape route was constructed from the visitors' changing rooms for use if the stadium was overrun by protestors. Crowds of anti-tour protestors stood outside as the police were overwhelmed but the hundreds of police still managed to prevent the protestors from entering the stadium.[25]

Christchurch

At Lancaster Park, Christchurch, on 15 August,[18] some protesters managed to break through a security cordon and a number invaded the pitch. They were quickly removed and forcibly ejected from the stadium by security staff and spectators. A large, well-coordinated street demonstration managed to occupy the streets immediately outside the ground and confront the riot police. Spectators were kept in the ground until the protesters dispersed.

Auckland: plane invasion

A low-flying Cessna 172 piloted by Marx Jones and Grant Cole disrupted the final test at Eden Park, Auckland, on 12 September[18] by dropping flour-bombs on the pitch. In spite of the bombing, the game continued.[26] "Patches" of criminal gangs, such as traditional rivals Black Power and the Mongrel Mob, were also evident (interestingly, the Black Power were Muldoon supporters[27]). Footage was shown of the Clowns Incident, where police were shown beating unarmed clowns with batons.[28]

The protest movement

Some of the protest had the dual purpose of linking alleged racial discrimination against Māori in New Zealand to apartheid in South Africa. Some of the protesters, particularly young Māori, felt frustrated by the image of New Zealand as a paradise for racial unity.[13] Many opponents of what they saw as racism in New Zealand in the early 1980s saw it as useful to use the protests against South Africa as a vehicle for wider social action. However, some Maori supported the tour and attended games.

Tour of the United States

With the American leg of the tour following directly after the events of New Zealand, further protests and clashes with police were expected.[2] Threats of riots caused city officials in Los Angeles, Chicago, New York City and Rochester to withdrew their previous authorisation for the Springboks to play in their cities.[2]

The Springboks' match against the Midwest All Stars team had originally been intended to be played in Chicago. Following the anti-apartheid protests, it was secretly rescheduled to the mid morning of Saturday 19 September at Roosevelt Park in Racine, Wisconsin.[29] The secret strategy seemingly worked as around 500 spectators gathered to watch the match. Late in game, however, a small number of protestors arrived to disrupt proceedings and two were arrested after a brief altercation broke out on the field.[29]

Albany: pipe bomb

The cancelled New York City match against the Eastern All Stars was moved upstate to Albany.[30] The long serving Mayor of Albany, Erastus Corning, maintained that there was a right of peaceful assembly to “publicly espouse an unpopular cause,” despite his own stated view that “I abhor everything about apartheid”.[29]

Governor Hugh Carey argued that the event should be barred as the anti-apartheid demonstrators presented an “imminent danger of riot”, but a Federal court ruling allowing the game to be played was upheld in the United States Court of Appeals. A further appeal to Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall was also overruled on the grounds of free speech.[30]

The match went ahead with around a thousand demonstrators (including Pete Seeger) corralled 100 yards away from the field of play, which was surrounded by the police. No violence occurred at the game but a pipe bomb was set off in the early morning outside the headquarters of the Eastern Rugby Union resulting in damage to the building estimated at $50,000.[30] No one was injured.

Glenville

The final match of the tour, against the United States national team, took place in secret at Glenville in upstate New York.[31] The thirty spectators recorded at the match is the lowest ever attendance for an international rugby match.[1]

The rugby

In New Zealand

| Date | Venue | Team | Winner and score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wed 22 July | Gisborne | Poverty Bay | SA 6–24 |

| Sat 25 July | Hamilton | Waikato | cancelled |

| Wed 29 July | New Plymouth | Taranaki | SA 9–34 |

| Sat 1 August | Palmerston North | Manawatu | SA 19–31 |

| Wed 5 August | Wanganui | Wanganui | SA 9–45 |

| Sat 8 August | Invercargill | Southland | SA 6–22 |

| Tues 11 August | Dunedin | Otago | SA 13–17 |

| Sat 15 August | Christchurch | New Zealand (1st Test) | NZ 14–9 |

| Tues 19 August | Timaru | South Canterbury | cancelled |

| Sat 22 August | Nelson | Nelson Bays | SA 0–83 |

| Tues 25 August | Napier | NZ Maori | 12–12 |

| Sat 29 August | Wellington | New Zealand (2nd Test) | SA 12–24 |

| Tues 2 September | Rotorua | Bay of Plenty | SA 24–29 |

| Sat 5 September | Auckland | Auckland | SA 12–39 |

| Tues 8 September | Whangarei | North Auckland | SA 10–19 |

| Sat 12 September | Auckland | New Zealand (3rd Test) | NZ 25–22 |

In United States

| Date | Venue | Team | Winner and score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sat 19 September | Racine, WI | Midwest All Stars | SA 46–12 |

| Tue 22 September | Albany, NY | Eastern All Stars | SA 41–0 |

| Fri 25 September | Glenville, NY | United States (Test match) | SA 38–7 |

Aftermath

The Muldoon government was re-elected in the 1981 election losing three seats to leave it with a majority of one.

The NZRU constitution contained much high-minded wording about promoting the image of rugby and New Zealand, and generally being a benefit to society. In 1985 the NZRU proposed an All Black tour of South Africa. Two lawyers successfully sued it, claiming such a tour would breach its constitution. A High Court injunction by Justice Casey stopped the tour.[33][34] The All Blacks did not tour South Africa until after the fall of the apartheid régime (1990–1994), although after the 1985 tour was cancelled an unofficial tour took place in 1986 by a team that included 28 out of the 30 All Blacks selected for the 1985 tour, known as the New Zealand Cavaliers but often advertised in South Africa as the All Blacks or depicted with the Silver Fern.

The role of the police also became more controversial as a result of the tour.

The All Blacks won the 1987 Rugby World Cup and rugby union was once again the dominant sport – in both spectator and participant numbers – in New Zealand.[35]

In New Zealand culture

- Prominent artist Ralph Hotere painted a Black Union Jack series of paintings in protest against the tour.

- Merata Mita's documentary film Patu! tells the tale of the tour from a left-wing perspective.[36]

- John Broughton wrote the play 1981 examining the way the tour divided a family.

- Music popularly associated with the tour included the punk band RIOT 111, and the songs "Riot Squad" by the Newmatics and "There Is No Depression In New Zealand" by Blam Blam Blam.[37]

- Ross Meurant, commander of the police "Red squad", published Red Squad Story in 1982, giving a conservative view. ISBN 978-0-908630-06-6

- The TVNZ 1980s police drama Mortimer's Patch included a flashback episode of the (younger) main character's tour police duties

- In 1984 Geoff Chapple wrote the book 1981: The Tour, chronicling the events from the protesters' perspective. ISBN 978-0-589-01534-3

- In 1999 Glenn Wood's biography Cop Out covered the tour from the perspective of a frontline policeman. ISBN 978-0-908704-89-7

- David Hill's book The Name of the Game is the story of a schoolboy's personal struggles during the tour. ISBN 978-0-908783-63-2

- Tom Newnham's book By Batons And Barbed Wire is one of the largest collections of photos and general information of the protest movement during the tour. ISBN 978-0-473-00253-4 (hardback). ISBN 978-0-473-00112-4 (paperback)

- The documentary 1981: A Country At War chronicled the tour from various perspectives.[38]

- Te Papa has objects related to the tour including images, helmets[39][40] and an entrance ticket.[41] The exhibition Slice of Heaven: 20th Century Aotearoa has a section about the tour.[42]

- Rage, a dramatisation of the tour by Tom Scott, was filmed in mid-2011[43][44] and was broadcast on TV One on 4 September 2011.[45]

- The Engine Room, a play by Ralph McCubbin Howell, opened at BATS Theatre in Wellington on 27 September 2011. It contrasts the stories and viewpoints of John Key and Helen Clark during the tour and the 2008 general election.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Springbok Tour. |

- 1971 South Africa rugby union tour of Australia

- History of South Africa in the apartheid era

- John Minto

- Robert Muldoon

- Ces Blazey

- New Zealand Cavaliers

- Politics and sports

- Sporting boycott of South Africa

Notes and references

- 1 2 Miller, Chuck (10 April 1995). "Rugby in the national spotlight: The 1981 USA tour of the Springboks". Rugby Magazine. Archived from the original on 22 October 2007. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- 1 2 3 Grondahl, Paul (6 December 2013). "All eyes were on Albany and Apartheid in 1981". Times Union. Archived from the original on 13 May 2015. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ↑ "All Blacks versus Springboks". nzhistory.net.nz. 12 June 2014. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- 1 2 Watters, Steve. "A long tradition of rugby rivalry". nzhistory.net.nz. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- 1 2 3 Watters, Steve. "'Politics and sport don't mix'". nzhistory.net.nz. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- 1 2 Watters, Steve. "Stopping the 1973 tour". nzhistory.net.nz. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ↑ Fortuin, Gregory (20 July 2006). "It's time to close the final chapter". The New Zealand Herald.

- ↑ "On This Day 17 July 1976". bbc.co.uk. 17 July 1976. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ↑ Watters, Steve. "From Montreal to Gleneagles". nzhistory.net.nz. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ↑ "When talk of racism is just not cricket". The Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax. 16 December 2005. Retrieved 19 August 2007.

- ↑ Chapple 1984, p. 60.

- ↑ "Politics and sport – 1981 Springbok tour". New Zealand history online. Nzhistory.net.nz. 24 February 2009. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- 1 2 "Battle lines are drawn – 1981 Springbok tour | NZHistory.net.nz, New Zealand history online". Nzhistory.net.nz. 24 February 2009. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- 1 2 "Impact – 1981 Springbok tour |". Nzhistory.net.nz. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ↑ Ardern, Crystal (22 July 2006). "Springbok Tour 1981". Waikato Times. Archived from the original on 15 October 2008.

- ↑ "Protest! The Voice of Dissent at the Nelson Provincial Museum" (PDF 0.4 MB). Evidence. New Zealand Police Museum. April 2007. p. 2. Retrieved 15 October 2008.

- ↑ "Springbok Tour Special | CLOSE UP News". TVNZ. 4 July 2006. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 "Tour diary – 1981 Springbok tour". New Zealand history online. Nzhistory.net.nz. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- 1 2 Film: game cancelled in Hamilton, 1981 Springbok tour, Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Updated 11 May 2007. Retrieved 24 December 2008.

- ↑ Chapple, pp. 77–78, 91, 99–102.

- ↑ "Film: game cancelled in Hamilton, 1981 Springbok tour | NZHistory.net.nz, New Zealand history online". Nzhistory.net.nz. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ↑ "Film: clash on Molesworth St – 1981 Springbok tour | NZHistory.net.nz, New Zealand history online". Nzhistory.net.nz. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ↑ Eddie Gay (24 May 2008). "Minto's battered helmet to go on display at Te Papa". NZ Herald. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ↑ "Lecturer admits 1981 tour sabotage", The Press, 14 July 2001.

- ↑ Gay, Edward (7 August 2008). "Eden Park revamp uncovers secret escape route". New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- ↑ "Film: the third test – 1981 Springbok tour | NZHistory.net.nz, New Zealand history online". NZ Herald. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ↑ Hazlehurst, Kayleen M; Hazlehurst, Cameron, eds. (2008). Gangs and youth subcultures. Transaction.

- ↑ Bingham, Eugene (11 August 2001). "The code of silence over a tour's infamous bashing". NZ Herald. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 1981: Secret site curbs rugby protest. The Journal Times. 8 September 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Protesters in Albany shout as Springboks triumph in rainfall. New York Times. 23 September 1981.

- 1 2 A Test of the Times. Houston Press. 13 December 2001.

- ↑ Tour diary – 1981 Springbok tour | NZHistory

- ↑ Adlam, Geoff. "Rt Hon Sir Maurice Eugene Casey, 1923 – 2012". New Zealand Law Society. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ↑ Tahana, Yvonne (21 January 2012). "Judge's ruling halted divisive All Black tour". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ↑ McMurran, Alister (18 November 2005). "'87 Cup healed '81 tour's wounds". Otago Daily Times.

- ↑ "NZ Feature Project: Patu!". New Zealand Film Archive. 4 August 2006. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ↑ The Film Archive – Ready to Roll? | Blam Blam Blam – There is no Depression

- ↑ "1981: Hitting the Road". New Zealand Film Archive. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ↑ "Helmet". Collections Online. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- ↑ "Helmet". Collections Online. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- ↑ "Ticket to Springboks versus Waikato rugby game at Rugby Park in Hamilton on 25 July 1981". Collections Online. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- ↑ "1981 Springbok tour". Slice of Heaven – Diversity & civil rights. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- ↑ NZ On Air | News | Press Releases

- ↑ Rothwell, Kimberley (19 May 2011). "Springbok tour upheaval re-enacted with Rage". Stuff: Entertainment. Fairfax. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ↑ TVNZ Sunday Theatre webpage

Bibliography

- Cameron, Don (1981). Barbed Wire Boks. Auckland, New Zealand: Rugby Press Ltd. ISBN 978-0-908630-05-9.

- Chapple, Geoff (1984). 1981: The Tour. Wellington: A H & A W Reed. ISBN 978-0-589-01534-3.

- Newnham, Tom (1981). By Batons and Barbed Wire. New Zealand: Real Pictures Ltd. ISBN 978-0-473-00112-4.

- Richards, Trevor (1999). Dancing on Our Bones: New Zealand, South Africa, Rugby and Racism. Wellington, New Zealand: Bridget Williams Books. ISBN 1-877-242-004.

External links

- Posters at Christchurch City Libraries

- Images of the events surrounding the Springbok Tour in the collection of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

- Online account

- A time line and references

- The 1981 Springbok Tour

- The 1981 Springbok Tour, including history, images and video (NZHistory)

- Letters solicited from the New Zealand public after the 1981 Springbok Tour

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||