1970s in Angola

| Angola | |

| This article is part of the series: 20th century of Angola | |

| 1900s | |

| 1910s | |

| 1920s | |

| 1930s | |

| 1940s | |

| 1950s | |

| 1960s | |

| War of Independence (1961 to 1975) | |

| 1970-1975 (1970s) | |

| Civil War (1975 to 2002) | |

| 1980s | |

| 1990s | |

| 2000s | |

The 1970s in Angola, a time of political and military turbulence, saw the end of Angola's War of Independence (1961–1975) and the outbreak of civil war (1975–2002). Agostinho Neto, the leader of the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), declared the independence of the People's Republic of Angola on November 11, 1975, in accordance with the Alvor Accords.[1] UNITA and the FNLA also declared Angolan independence as the Social Democratic Republic of Angola based in Huambo and the Democratic Republic of Angola based in Ambriz. FLEC, armed and backed by the French government, declared the independence of the Republic of Cabinda from Paris.[2] The National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA) and the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA)) forged an alliance on November 23, proclaiming their own coalition government based in Huambo[3] with Holden Roberto and Jonas Savimbi as co-presidents and José Ndelé and Johnny Pinnock Eduardo as co-Prime Ministers.[4]

The South African government told Savimbi and Roberto in early November that the South African Defence Force (SADF) would soon end operations in Angola despite the coalition's failure to capture Luanda and therefore secure international recognition at independence. Savimbi, desperate to avoid the withdrawal of the largest, friendly, military force in Angola, asked General Constand Viljoen to arrange a meeting for him with South African Prime Minister John Vorster, Savimbi's ally since October 1974. On the night of November 10, the day before independence, Savimbi secretly flew to Pretoria, South Africa and the meeting took place. In a remarkable reversal of policy, Vorster not only agreed to keep troops through November but promised to withdraw the SADF troops only after the OAU meeting on December 9.[5][6] The Soviets, well aware of South African activity in southern Angola, flew Cuban soldiers into Luanda the week before independence. While Cuban officers led the mission and provided the bulk of the troop force, 60 Soviet officers in the Congo joined the Cubans on November 12. The Soviet leadership expressly forbid the Cubans from intervening in Angola's civil war, focusing the mission on containing South Africa.[7]

In 1975 and 1976 most foreign forces, with the exception of Cuba, withdrew. The last elements of the Portuguese military withdrew in 1975[8] and the South African military withdrew in February 1976.[9] On the other hand, Cuba's troop force in Angola increased from 5,500 in December 1975 to 11,000 in February 1976.[10] FNLA forces were crushed by Operation Carlota, a joint Cuban-Angolan attack on Huambo on January 30, 1976.[11] By mid-November, the Huambo government had gained control over southern Angola and began pushing north.[12]

Clark Amendment

President Gerald Ford approved covert aid to UNITA and the FNLA through Operation IA Feature on July 18, 1975, despite strong opposition from officials in the State Department and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Ford told William Colby, the Director of Central Intelligence, to "go ahead and do it" with an initial US$6 million in funding. He granted an additional $8 million in funding on July 27 and another $25 million in August.[13][14]

Two days prior to the program's approval, Nathaniel Davis, the Assistant Secretary of State, told Henry Kissinger, the Secretary of State, that he believed maintaining the secrecy of IA Feature would be impossible. Davis correctly predicted the Soviet Union would respond by increasing involvement in the Angolan conflict, leading to more violence and negative publicity for the United States. When Ford approved the program, Davis resigned.[15] John Stockwell, the CIA's station chief in Angola, echoed Davis' criticism saying the success required expanding the program, but the program's size already exceeded what could be hidden from the public eye. Davis' deputy, former U.S. ambassador to Chile Edward Mulcahy, also opposed direct involvement. Mulcahy presented three options for U.S. policy towards Angola on May 13, 1975. Mulcahy believed the Ford administration could use diplomacy to campaign against foreign aid to the Communist MPLA, refuse to take sides in factional fighting, or increase support for the FNLA and UNITA. He warned however that supporting UNITA would not sit well with Mobutu Sese Seko, the ruler of Zaire.[13][16]

Dick Clark, a Democratic Senator from Iowa, discovered the operation during a fact-finding mission in Africa, but Seymour Hersh, a reporter for The New York Times, revealed IA Feature to the public on December 13, 1975.[17] Clark proposed an amendment to the Arms Export Control Act, barring aid to private groups engaged in military or paramilitary operations in Angola. The Senate passed the bill, voting 54–22 on December 19, 1975 and the House passed the bill, voting 323–99 on January 27, 1976.[14] Ford signed the bill into law on February 9, 1976.[18] Even after the Clark Amendment became law, then-Director of Central Intelligence, George H. W. Bush, refused to concede that all U.S. aid to Angola had ceased.[19][20] According to foreign affairs analyst Jane Hunter, Israel stepped in as a proxy arms supplier for the United States after the Clark Amendment took effect.[21]

The U.S. government vetoed Angolan entry into the United Nations on June 23, 1976.[22] Zambia forbid UNITA from launching attacks from its territory after Angola became a member of the UN[23] on December 1, 1976.[24]

Vietnam

The Vietnam War tempered foreign involvement in Angola's civil war as neither the Soviet Union nor the United States wanted to be drawn into an internal conflict of highly debatable importance in terms of winning the Cold War. CBS Newscaster Walter Cronkite spread this message in his broadcasts to "try to play our small part in preventing that mistake this time."[25] The Politburo engaged in heated debate over the extent to which the Soviet Union would support a continued offensive by the MPLA in February 1976. Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko and Premier Alexei Kosygin led a faction favoring less support for the MPLA and greater emphasis on preserving détente with the West. Leonid Brezhnev, the then head of the Soviet Union, won out against the dissident faction and the Soviet alliance with the MPLA continued even as Neto publicly reaffirmed its policy of non-alignment at the 15th anniversary of the First Revolt.[26]

Angolan government and Cuban troops had control over all southern cities by 1977, but roads in the south faced repeated UNITA attacks. Savimbi expressed his willingness for rapprochement with the MPLA and the formation of a unity, socialist government, but he insisted on Cuban withdrawal first. "The real enemy is Cuban colonialism," Savimbi told reporters, warning, "The Cubans have taken over the country, but sooner or later they will suffer their own Vietnam in Angola." Government and Cuban troops used flame throwers, bulldozers, and planes with napalm to destroy villages in a 1.6 mile wide area along the Angola-Namibia border. Only women and children passed through this area, "Castro Corridor," because government troops had shot all males ten years of age or older to prevent them from joining the UNITA. The napalm killed cattle to feed government troops and to retaliate against UNITA sympathizers. Angolans fled from their homeland; 10,000 going south to Namibia and 16,000 east to Zambia, where they lived in refugee camps.[23] Foreign Secretary Lord Carrington of the United Kingdom expressed similar concerns over British involvement in Rhodesia's Bush War during the Lancaster House negotiations in 1980.[27]

Shaba invasions

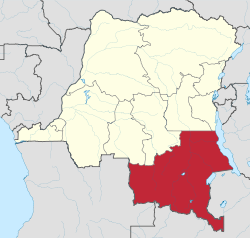

1,500 members of the Front for the National Liberation of the Congo (FNLC) invaded Shaba, Zaire from eastern Angola on March 7, 1977. The FNLC wanted to overthrow Mobutu and the Angolan government, suffering from Mobutu's support for the FNLA and UNITA, did not try to stop the invasion. The FNLC failed to capture Kolwezi, Zaire's economic heartland, but took Kasaji, and Mutshatsha. Zairian troops were defeated without difficulty and the FNLC continued to advance. Mobutu appealed to William Eteki of Cameroon, Chairman of the Organization of African Unity, for assistance on April 2. Eight days later, the French government responded to Mobutu's plea and airlifted 1,500 Moroccan troops into Kinshasa. This troop force worked in conjunction with the Zairian army and the FNLA[28] of Angola with air cover from Egyptian pilots flying French Mirage fighter aircraft to beat back the FNLC. The counter-invasion force pushed the last of the militants, along with a number of refugees, into Angola and Zambia in April.[29][30][31][32]

Mobutu accused the Angolan government, as well as the Cuban and Soviet governments, of complicity in the war.[33] While Neto did support the FNLC, the Angolan government's support came in response to Mobutu's continued support for Angola's anti-Communists.[34] The Carter Administration, unconvinced of Cuban involvement, responded by offering a meager $15 million-worth of non-military aid. American timidity during the war prompted a shift in Zaire's foreign policy from the U.S. to France, which became Zaire's largest supplier of arms after the intervention.[35] Neto and Mobutu signed a border agreement on July 22, 1977.[36]

John Stockwell, the Central Intelligence Agency's station chief in Angola, resigned after the invasion, explaining in an article for The Washington Post article Why I'm Leaving the CIA, published on April 10, 1977 that he had warned Secretary of State Henry Kissinger that continued American support for anti-government rebels in Angola could provoke a war with Zaire. He also said covert Soviet involvement in Angola came after, and in response to, U.S. involvement.[37]

The FNLC invaded Shaba again on May 11, 1978, capturing Kolwezi in two days. While the Carter Administration had accepted Cuba's insistence on its non-involvement in Shaba I, and therefore did not stand with Mobutu, the U.S. government now accused Castro of complicity.[38] This time, when Mobutu appealed for foreign assistance, the U.S. government worked with the French and Belgian militaries to beat back the invasion, the first military cooperation between France and the United States since the Vietnam War.[39][40] The French Foreign Legion took back Kolwezi after a seven-day battle and airlifted 2,250 European citizens to Belgium, but not before the FNLC massacred 80 Europeans and 200 Africans. In one instance the FNLC killed 34 European civilians who had hidden in a room. The FNLC retreated to Zambia and back to Angola, vowing to return. The Zairian army then forcibly evicted civilians along Shaba's 65-mile long border with Angola and Mobutu ordered them to shoot on sight.[41]

U.S. mediated negotiations between the Angolan and Zairian governments led to a peace accord and an end to support for insurgencies in each other's respective countries. Zaire temporarily cutoff support to FLEC, the FNLA, and UNITA and Angola forbid further activity by the FNLC.[39]

Nitistas

Neto's Interior Minister, Nito Alves, had successfully put down Daniel Chipenda's Eastern Revolt and the Active Revolt during Angola's War of Independence. Factionalism within the MPLA became a major challenge to Neto's power by late 1975 and he gave Alves the task of once again clamping down on dissension. Alves shut down the Cabral and Henda Committees while expanding his influence within the MPLA through his control of the nation's newspapers and state-run television. Alves visited the Soviet Union in October 1976. When he returned, Neto began taking steps to neutralize the threat he saw in the Nitistas, followers of Alves. Neto called a plenum meeting of the Central Committee of the MPLA. Neto formally designated the party Marxist-Leninist, abolished the Interior Ministry and DOM, the official branch of the MPLA used by the Nitistas, and established a Commission of Enquiry. Neto used the commission, officially created to examine and report factionalism, to target the Nitistas, and ordered the commission to issue a report of its findings in March 1977. Alves and Chief of Staff José Van-Dunem, his political ally, began planning a coup d'état against dos Santos.[42]

Alves represented the MPLA at the 25th Soviet Communist Party Congress in February 1977 and may have then obtained support for the coup from the Soviet Union. Alves and Van-Dunem planned to arrest Neto on May 21 before he arrived at a meeting of the Central Committee and before the commission released its report. The MPLA changed the meeting's location shortly before its scheduled start, throwing the plotters' plans into disarray, but Alves attended the meeting and faced the commission anyway. The commission released its report, accusing him of factionalism. Alves fought back, denouncing Neto for not aligning Angola with the Soviet Union. After twelve hours of debate, the party voted 26 to 6 to kick Alves and Van-Dunem out of power.[42]

Ten armored cars with the FAPLA's 8th Brigade broke into São Paulo prison at 4 a.m. on May 27, killing the prison warden and freeing more than 150 supporters, including 11 who had been arrested only a few days before. The brigade took control of the radio station in Luanda at 7 a.m. and announced their coup, calling themselves the MPLA Action Committee. The brigade asked citizens to show their support for the coup by demonstrating in front of the presidential palace. The Nitistas captured Bula and Dangereaux, generals loyal to Neto, but Neto had moved his base of operations from the palace to the Ministry of Defence in fear of such an uprising. Cuban troops retook the palace at Neto's request and marched to the radio station. After an hour of fighting, the Cubans succeeded and proceeded to the barracks of the 8th brigade, recaptured by 1:30 p.m. While the Cuban force captured the palace and radio station, the Nitistas kidnapped seven leaders within the government and the military, shooting and killing six.[43]

The government arrested tens of thousands of suspected Nitistas from May to November and tried them in secret courts overseen by Defense Minister Iko Carreira. Those who were found guilty, including Van-Dunem, Jacobo "Immortal Monster" Caetano, the head of the 8th Brigade, and political commissar Eduardo Evaristo, were then shot and buried in secret graves. The coup attempt had a lasting effect on Angola's foreign relations. Alves had opposed Neto's foreign policy of non-alignment, evolutionary socialism, and multiracialism, favoring stronger relations with the Soviet Union, which he wanted to grant military bases in Angola. While Cuban soldiers actively helped Neto put down the coup, Alves and Neto both believed the Soviet Union supported Neto's ouster. Raúl Castro sent an additional four thousand troops to prevent further dissension within the MPLA's ranks and met with Neto in August in a display of solidarity. In contrast, Neto's distrust in the Soviet leadership increased and relations with the USSR worsened.[43] In December, the MPLA held is first party Congress and changed its name to the MPLA-PT. The Nitista coup took a toll on the MPLA's membership. In 1975, the MPLA boasted of 200,000 members. After the first party congress, that number decreased to 30,000.[42][44][45][46][47]

Rise of dos Santos

On July 5, 1979, Neto issued a decree requiring all citizens to serve in the military for three years upon turning the age of eighteen. The government gave a report to the UN estimating $293 million in property damage from South African attacks between 1976 and 1979, asking for compensation on August 3, 1979. The Popular Movement for the Liberation of Cabinda, a Cabindan separatist rebel group, attacked a Cuban base near Tshiowa on August 11.[48]

President Neto died from inoperable cancer in Moscow on September 10, 1979. Lúcio Lara and Pascual Luvualo flew to Moscow and the MPLA declared 45 days of mourning. The government held his funeral at the Palace of the People on September 17. Many foreign dignitaries, including Organization of African Unity President William R. Tolbert, Jr. of Liberia, attended. The Central Committee of the MPLA unanimously voted in favor of José Eduardo dos Santos as President. He was sworn in on September 21. Under dos Santos' leadership, Angolan troops crossed the border into Namibia for the first time on October 31, going into Kavango. The next day, the governments of Angola, Zambia, and Zaire signed a non-aggression pact.[48]

See also

References

- ↑ Rothchild, Donald S. (1997). Managing Ethnic Conflict in Africa: Pressures and Incentives for Cooperation. pp. 115–116.

- ↑ Mwaura, Ndirangu (2005). Kenya Today: Breaking the Yoke of Colonialism in Africa. pp. 222–223.

- ↑ Crocker, Chester A.; Hampson, Fen Osler; Aall, Pamela R. (2005). Grasping The Nettle: Analyzing Cases Of Intractable Conflict. p. 213.

- ↑ Kalley, Jacqueline Audrey (1999). Southern African Political History: A Chronology of Key Political Events from Independence to Mid-1997. p. 1–2.

- ↑ Hilton, Hamann (2001). Days of the Generals. p. 34.

- ↑ Preez, Max Du (2003). Pale Native. p. 84.

- ↑ Westad, Odd Arne (2005). The Global Cold War: Third World Interventions and the Making of Our Times. p. 230–235.

- ↑ Martin, Peggy J.; Kaplan; Kaplan Staff (2005). SAT Subject Tests: World History 2005–2006. p. 316.

- ↑ Stearns, Peter N.; Langer, William Leonard (2001). The Encyclopedia of World History: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern, Chronologically Arranged. p. 1065.

- ↑ Mazrui, Ali Al 'Amin (1977). The Warrior Tradition in Modern Africa. p. 227.

- ↑ Angola Reds on Outskirts of Pro-Western capital city, January 30, 1976. The Argus, page 10, via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ↑ Porter, Bruce D. (1986). The USSR in Third World Conflicts: Soviet Arms and Diplomacy in Local Wars. p. 149.

- 1 2 Andrew, Christopher M. (1995). For the President's Eyes Only: Secret Intelligence and the American Presidency from Washington to Bush. p. 412.

- 1 2 Immerman, Richard H.; Theoharis, Athan G. (2006). The Central Intelligence Agency: Security Under Scrutiny. p. 325.

- ↑ Brown, Seyom (1994). The Faces of Power: Constancy and Change in United States Foreign Policy from Truman to Clinton. p. 303.

- ↑ Hanhim̀eaki, Jussi M. (2004). The Flawed Architect: Henry Kissinger and American Foreign Policy. p. 408.

- ↑ Baravalle, Giorgio (2004). Rethink: Cause and Consequences of September 11. p. cdxcii.

- ↑ Gates, Robert Michael (2007). From the Shadows: The Ultimate Insider's Story of Five Presidents and How They Won the Cold War. p. 68.

- ↑ Koh, Harold Hongju (1990). The National Security Constitution: Sharing Power After the Iran-Contra Affair. Yale University Press. ISBN.p. 52

- ↑ Fausold, Martin L.; Alan Shank (1991). The Constitution and the American Presidency. SUNY Press. ISBN. Pages 186–187.

- ↑ Wayne Madsen (2002). "Report Alleges US Role in Angola Arms-for-Oil Scandal". CorpWatch. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- ↑ Kalley (1999). Page 4.

- 1 2 Unknown (January 17, 1977). "'Absolute Hell Over There'". TIME Magazine. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ↑ Unknown. "Our Former Ambassadors" (PDF). United Nations. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ↑ Unknown (December 29, 1975). "The Battle Over Angola". TIME Magazine. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ↑ Unknown (February 16, 1976). "Angola's Three Troubled Neighbors". TIME Magazine. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ↑ Unknown (January 7, 1980). "Carrington on Rhodesia". TIME Magazine. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ↑ Garthoff, Raymond Leonard (1985). Détente and Confrontation: American-Soviet Relations from Nixon to Reagan. p. 624.

- ↑ Schraeder, Peter J. (1999). United States Foreign Policy Toward Africa: Incrementalism, Crisis and Change. p. 87–88.

- ↑ Danopoulos, Constantine Panos; Watson, Cynthia Ann (1996). The Political Role of the Military: An International Handbook. p. 451.

- ↑ Ihonvbere, Julius Omozuanvbo; Mbaku, John Mukum (2003). Political Liberalization and Democratization in Africa: Lessons from Country Experiences. p. 228.

- ↑ Tanca, Antonio (1993). Foreign Armed Intervention in Internal Conflict. p. 169.

- ↑ Dunn, Kevin C (2003). Imagining the Congo: The International Relations of Identity. p. 129.

- ↑ Mukenge, Tshilemalema (2002). Culture and Customs of the Congo. p. 31.

- ↑ Vine, Victor T. Le (2004). Politics in Francophone Africa. p. 381.

- ↑ Osmâanczyk, Edmund Jan; Mango, Anthony (2003). Encyclopedia of the United Nations and International Agreements. p. 95.

- ↑ Chomsky, Noam; Herman, Edward S. The political economy of human right. p. 308.

- ↑ Mesa-Lago, Carmelo; Belkin, June S. (1982). Cuba in Africa. p. 30–31.

- 1 2 George. (2005). Page 136.

- ↑ Gösta, Carl; Widstrand, Timothy M. Shaw, and Douglas George Anglin (1978). Canada, Scandinavia, and Southern Africa. p. 130.

- ↑ "Inside Kolwezi: Toll of Terror". TIME magazine. June 5, 1978. Retrieved 2007-09-20.

- 1 2 3 George, Edward (2005). The Cuban Intervention in Angola, 1965–1991: From Che Guevara to Cuito Cuanavale. p. 127–128.

- 1 2 George (2005). Pages 129–131.

- ↑ Hodges, Tony (2004). Angola: Anatomy of an Oil State. p. 50.

- ↑ Fauriol, Georges A.; Eva Loser (1990). Cuba: The International Dimension. p. 164.

- ↑ Domínguez, Jorge I. (1989). To Make a World Safe for Revolution: Cuba's Foreign Policy. p. 158.

- ↑ Radu, Michael S. (1990). The New Insurgencies: Anticommunist Guerrillas in the Third World. p. 134–135.

- 1 2 Kalley (1999). Page 12.