1954 Guatemalan coup d'état

| 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

|

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||

|

Jacobo Árbenz Carlos Enrique Díaz María Vilanova (asesor) |

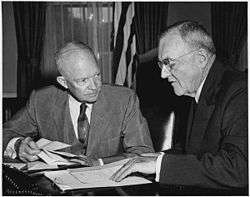

Elfego Hernán Monzón Aguirre Carlos Castillo Armas José Luis Cruz Salazar Mauricio Dubois Dwight D. Eisenhower | |||||||

The 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état was a covert operation carried out by the United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) that deposed the democratically elected Guatemalan President Jacobo Árbenz and ended the Guatemalan Revolution.[1] Code-named Operation PBSUCCESS, it installed the military dictatorship of Carlos Castillo Armas, the first in a series of U.S.-backed dictators who ruled Guatemala.

A popular revolution against the U.S.-backed dictator Jorge Ubico[2][3][4] in 1944 had led to Guatemala's first democratic election and the beginning of the Guatemalan Revolution.[5] The elections were won by Juan José Arévalo who wanted to turn Guatemala into a liberal capitalist society.[6] He implemented social reforms which included a minimum wage law, increased educational funding and near-universal suffrage. Arévalo's defense minister Jacobo Árbenz was elected President in 1950, and continued the social reform policies, as well as instituting land reform, which sought to grant land to peasants who had been victims of debt slavery prior to Arévalo. Despite their moderate policies, the Guatemalan Revolution was widely disliked by the United States government, which was predisposed by the Cold War to see it as communist, and the United Fruit Company (UFC), whose hugely profitable business had been affected by the end to brutal labor practices.[7][8] The attitude of the U.S. government was also influenced by a propaganda campaign carried out by the UFC.[9]

U.S. President Harry Truman authorized Operation PBFORTUNE to topple Árbenz in 1952, with the support of Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza García, but the operation was aborted when too many details became public. Dwight D. Eisenhower was elected U.S. President in 1952, promising to take a harder line against communism; the close links that his staff members John Foster Dulles and Allen Dulles had to the UFC also predisposed him to act against Árbenz. Eisenhower authorized the CIA to carry out Operation PBSUCCESS in August 1953. The CIA armed, funded, and trained a force of 480 men led by Carlos Castillo Armas. The force invaded Guatemala on 18 June 1954, backed by a heavy campaign of psychological warfare, including bombings of Guatemala City and an anti-Árbenz radio station claiming to be genuine news. The invasion force fared poorly militarily, but the psychological warfare and the possibility of a U.S. invasion intimidated the Guatemalan army, which refused to fight. Árbenz resigned on 27 June, and following negotiations in San Salvador, Carlos Castillo Armas became President on 7 July 1954.

The coup was widely criticized internationally, and created lasting anti-U.S. sentiment in Latin America. Castillo Armas quickly took dictatorial powers, banning all political parties, torturing and imprisoning political opponents, and reversing the social reforms of the Guatemalan Revolution. A series of U.S.-backed authoritarian governments ruled Guatemala until 1996. The repression sparked off the Guatemalan Civil War between the government and leftist guerrillas, during which the military committed massive human rights violations against the civilian population, including a genocidal campaign against the Maya peoples.[10] The coup has been described as the definitive deathblow to democracy in Guatemala.[11]

Historical background

.svg.png)

Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine was a philosophy of foreign policy articulated by U.S. President James Monroe in 1823. It warned the European powers not to indulge in further colonization in Latin America.[12][13] The stated aim of the doctrine was to maintain order and stability, and to make certain that access to resources and markets was not limited.[13] Historian Mark Gilderhus states that the doctrine also contained racially condescending language, which likened Latin American countries to fighting children.[13]

The U.S. did not initially have the power to enforce the Monroe Doctrine. Over the course of the 19th century many European powers withdrew from Latin America, and the U.S. expanded its sphere of influence.[12] In 1895, Grover Cleveland laid out a more militant version of the doctrine, stating that the U.S. was "practically sovereign" on the continent.[13] Following the Spanish–American War in 1898, this aggressive interpretation was used to create a U.S. economic empire across the Caribbean, such as with the 1903 treaty with Cuba that was heavily tilted in the U.S.' favor.[13] U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt believed that the U.S. should be the main beneficiary of production in Central America.[14] The U.S. enforced this hegemony with armed interventions in Nicaragua (1912–33), and Haiti (1915–34).[15] The U.S. did not need to use its military might in Guatemala, where a series of dictators were willing to accommodate U.S. economic interests in return for U.S. support.[15] From 1890 to 1920, economic control of Guatemalan resources and economy shifted away from Britain and Germany to the United States, which became the dominant Guatemalan trade partner.[15] The Monroe Doctrine continued to be applied to the country, and was used to justify the coup in 1954.[16]

Authoritarian governments

The surge in global coffee demand in the late 19th century led to the Guatemalan government making numerous concessions to plantation owners, such as by passing legislation that dispossessed the communal landholdings of the indigenous population and allowed coffee growers to purchase it.[17][18] Manuel Estrada Cabrera, president of Guatemala from 1898 to 1920, was one of several rulers who made huge concessions to foreign companies, including the United States-based United Fruit Company (UFC), which purchased large areas of land at favorable prices.[19] U.S. historian William Blum describes UFC's role in Guatemala as a "state within a state":[20] the company had a monopoly over the highly lucrative banana trade, and due to its close relationships with the Guatemalan dictators, also controlled the docks, the railroad, and the communications in the country.[21] The U.S. government was also closely involved with the Guatemalan state, frequently dictating financial policies, and ensuring that U.S. companies were granted several exclusive rights.[22] When Cabrera was overthrown in 1920, the U.S. sent an armed force to make certain that the new president remained friendly to the United States.[23]

Fearing a popular revolt following the unrest created by the Great Depression of 1929, wealthy Guatemalan landowners lent their support to Jorge Ubico, who had become known for his efficiency and ruthlessness as a provincial governor. Ubico won an uncontested election in 1931,[17][18] with the United States also lending him heavy political support.[23] Ubico's regime quickly became one of the most repressive in the region. He abolished debt peonage, replacing it with a vagrancy law, which stipulated that all landless men of working age needed to perform a minimum of 100 days of forced labor annually.[24] He authorized landowners to take any actions against their workers, including executions.[24][25][2] Ubico was a big admirer of European fascists like Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler, but was driven to ally with the United States for geopolitical reasons.[26] Following the American lead he declared war against Germany and Japan in 1941, and arrested all people of German descent in the country.[27] He continued to make massive concessions to the United Fruit Company, such as giving it 200,000 hectares (490,000 acres) of public land,[28] and exempting it from all taxes.[29]

Ubico amassed a large personal wealth, claiming an annual salary equivalent to 215,000 U.S. dollars.[29] He was strongly anti–communist, reacting to several peasant rebellions with incarcerations and massacres.[29][2][3][4] He held the indigenous Maya people in high contempt, likening them to donkeys.[2] Ubico continued to receive support from the U.S. right through his period in power.[30]

Guatemalan Revolution and Presidency of Arévalo

The repressive policies of the Ubico government resulted in a popular uprising led by university students and middle-class citizens in 1944.[6] Ubico fled, handing over power to a three-person junta led by Federico Ponce Vaides. The junta continued Ubico's policies until it was toppled by the October Revolution. The movement had the aim of transforming Guatemala into a liberal capitalist society.[6] The largely free election that followed installed a philosophically conservative university professor, Juan José Arévalo, as the President of Guatemala. Arévalo's administration drafted a more liberal labor code, built health centers, and increased funding to education. It stopped short of drastically changing labor relations in the countryside.[31] Arévalo enacted a minimum wage, and created state-run farms to employ landless laborers. He also cracked down on the communist party, and in 1945 criminalized all unions in workplaces with less than 500 workers.[32] By 1947, the remaining unions had grown strong enough to pressure him into drafting a new labor code, which made workplace discrimination illegal and created health and safety standards,[33] but Arévalo nonetheless refused to advocate land-reform of any kind.[31] Despite Arévalo's anti-communism, the United States was suspicious of him, and worried that he was under Soviet influence.[7] Another cause for U.S. worry was Arévalo's support of the Caribbean Legion, a group of progressive exiles, and revolutionaries who aimed to overthrow U.S. backed dictatorships across Central America.[34]

The government also faced opposition from within the country. Although popular among Guatemalan nationalists, Arévalo was disliked by the Catholic church and the military, and faced at least 25 unsuccessful coup attempts during his presidency.[35] Arévalo was prevented from contesting the 1950 elections by the constitution. The largely free elections were won by the popular Jacobo Árbenz, who had been one of the leaders of the October 1944 coup, and had served as defense minister to Arévalo.[36] Árbenz promised to continue and expand the reforms begun under Arévalo.[37] Despite having personal ties to some members of the communist Guatemalan Party of Labour which was legalized during his government,[36] Árbenz did not try to turn Guatemala into a communist country, instead choosing a moderate capitalist approach.[38]

Presidency of Árbenz and land reform

Under Árbenz, Guatemala constructed an Atlantic port and a highway to compete with United Fruit's holdings, and built a hydro-electric plant to offer cheaper energy than the US-controlled electricity monopoly. Arbenz's strategy was to limit the power of foreign companies through direct competition rather than through nationalization, except when it was impossible because a quantity was fixed, like land.[20]

The biggest component of Árbenz' policy was his agrarian reform bill.[39] Árbenz drafted the bill himself,[40] while also seeking advice from numerous economists from across Latin America.[39] The focus of the program was on transferring uncultivated land from large landowners to their poverty stricken laborers, who would then be able to begin a viable farm of their own.[39] Árbenz was also motivated to pass the bill because he needed to generate capital for his public infrastructure projects within the country. At the behest of the United States, the World Bank had refused to grant Guatemala a loan in 1951, which made the shortage of capital more acute.[41]

The official title of the agrarian reform bill was Decree 900. It expropriated all uncultivated land from landholdings that were larger than 673 acres (272 ha). If the estates were between 672 acres (272 ha) and 224 acres (91 ha) in size, uncultivated land was expropriated only if less than two-thirds of it was in use.[41] The owners were compensated with government bonds, the value of which was equal to that of the land expropriated. The value of the land itself was the value that the owners had declared in their tax returns in 1952.[41] Of the nearly 350,000 private land-holdings, only 1710 were affected by expropriation. The law itself was cast in a moderate capitalist framework; it was implemented with great speed, which resulted in occasional arbitrary land seizures. There was also some violence, directed at land-owners, as well as at peasants that had minor landholdings.[41]

By June 1954, 1.4 million acres of land had been expropriated and distributed. Approximately 500,000 individuals, or one-sixth of the population, had received land by this point.[41] The decree also included provision of financial credit to the people who received the land. The National Agrarian Bank (Banco Nacional Agrario, or BNA) was created on 7 July 1953.[41] The BNA developed a reputation for being a highly efficient government bureaucracy.[41] The loans had a high repayment rate; of the 3,371,185 U.S. dollars paid out between March and November 1953, 3,049,092 dollars had been repaid by June 1954.[41] The law also nationalized roads that passed through redistributed land, which greatly improved the connectivity of rural communities.[41]

Contrary to the predictions made by detractors of the government, the law resulted in a slight increase in Guatemalan agricultural productivity, and to an increase in cultivated area. Purchases of farm machinery also increased.[41] Overall, the law resulted in a significant improvement in living standards for many thousands of peasant families, the majority of whom were indigenous people. [41] Historian Piero Gleijeses stated that the injustices corrected by the law were far greater than the injustice of the relatively few arbitrary land seizures.[41] Historian Greg Grandin stated that the law was flawed in many respects; among other things, it was too cautious and deferential to the planters, and it created communal divisions among peasants. Nonetheless, it represented a fundamental power shift in favor of those that had been marginalized before then.[42]

Role of the United Fruit Company

History

The United Fruit Company (UFC) had been formed in 1899 by the merger of two large American corporations.[43] The new corporation held large tracts of land across Central America, and also controlled the railroads in the region, which it used to support its business of exporting bananas.[44] By 1900 it had become the largest exporter of bananas in the world.[45] By 1930 it had an operating capital of 215 million U.S. dollars, and had been the largest landowner and employer in Guatemala for several years.[46] Under the dictatorships of Manuel Estrada Cabrera and Jorge Ubico, the company had been granted a large number of economic and legal concessions in Guatemala that allowed it to massively expand its business. These concessions frequently came at the cost of tax revenue for the Guatemalan government.[45] The company supported Jorge Ubico in the leadership struggle that occurred from 1930 to 1932, and upon assuming power, Ubico expressed willingness to create a new contract with it. This new contract was immensely favorable to the company. It included a 99-year lease to massive tracts of land, exemptions from virtually all taxes, and a guarantee that no other company would receive any competing contract. Under Ubico, the company paid virtually no taxes, which greatly hindered the Guatemalan government's ability to deal with the Great Depression of 1929–32.[45] Ubico requested the UFC to cap the salary of its workers at only 50 cents a day, so that workers in other companies would be less able to demand higher wages.[46] The company also virtually owned Puerto Barrios, Guatemala's only port to the Atlantic Ocean, allowing the company to make profits from the flow of goods through the port.[46] By 1950, the company's annual profits were 65 million U.S. dollars, twice as large as the revenue of the government of Guatemala.[47]

Effects of the October revolution

Due to its long association with Ubico's government, the United Fruit Company (UFC) was seen as an impediment to progress by Guatemalan revolutionaries after 1944. This image was worsened by the company's discriminatory policies towards its colored workers.[48][49] Thanks to its position as the country's largest landowner and employer, the reforms of Arévalo's government affected the UFC more than other companies. Among other things, the labor code passed by the government allowed its workers to strike when their demands for higher wages and job security were not met. The company saw itself as being specifically targeted by the reforms, and refused to negotiate with the numerous sets of strikers, despite frequently being in violation of the new laws.[50] The company's labor troubles were compounded in 1952 when Jacobo Árbenz passed Decree 900, the agrarian reform law. Of the 550,000 acres (220,000 ha) that the company owned, 15% were being cultivated; the rest of the land, which was idle, came under the scope of the agrarian reform law.[50]

Lobbying the United States

The United Fruit Company responded with intensive lobbying of members of the United States government, leading many U.S. congressmen and senators to criticize the Guatemalan government for not protecting the interests of the company.[51] The Guatemalan government responded by saying that the company was the main obstacle to progress in the country. American historians observed that "To the Guatemalans it appeared that their country was being mercilessly exploited by foreign interests which took huge profits without making any contributions to the nation's welfare."[51] In 1953, 200,000 acres (81,000 ha) of uncultivated land was expropriated by the government, which offered the company compensation at the rate of 2.99 U.S. dollars to the acre (7.39 U.S. dollars per hectare), twice what the company had paid when it bought the property.[51] More expropriation occurred soon after, bringing the total to over 400,000 acres (160,000 ha); the government offered compensation to the company at the rate at which the UFC had valued its own property for tax purposes.[50] This resulted in further lobbying in Washington, particularly through Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, who had close ties to the company.[51] The company began a public relations campaign to discredit the Guatemalan government; it hired public relations expert Edward Bernays, who ran a concerted campaign of misinformation to portray the company as the victim of the Guatemalan government for several years.[52] The company stepped up its efforts after Dwight Eisenhower had been elected in 1952. These included commissioning a research study on Guatemala from a firm known to be hawkish, which produced a 235-page report that was highly critical of the Guatemalan government.[53] Historians have stated that the report was full of "exaggerations, scurrilous descriptions and bizarre historical theories."[53] The report nonetheless had a significant impact on the members of Congress that it was sent to. Overall, the company spent over a half-million U.S. dollars to influence both lawmakers and members of the public in the U.S. that the Guatemalan government needed to be overthrown.[53]

Operation PBFORTUNE

The U.S. government had become more hostile to the new Guatemalan government over the years of Arévalo's presidency. This was due partly to the intensification of the cold war, as well as a reduction in the massive concessions that the United Fruit Company had enjoyed under Ubico.[54] In addition, the company carried out an intensive lobbying campaign within the U.S. to discredit the Guatemalan government.[55] The worries of the U.S. increased after the election of Jacobo Árbenz in 1951 and his enactment of Decree 900, the agrarian reform law, in 1952.[54][56] The new law benefited approximately half a million people;[41] several hundred thousand acres of uncultivated land belonging to the United Fruit Company were expropriated. The compensation it was granted was based on the valuation the company had used for its tax payments. Since this was a major undervaluation, the company was unhappy with its compensation,[51] and intensified its lobbying against the Guatemalan government in Washington.[51]

In April 1952 Anastasio Somoza García, the U.S.-backed dictator of Nicaragua, made his first state visit to the U.S.[57] Somoza made several public speeches praising the United States, and was awarded a medal by New York City.[58] During a meeting with Truman and his senior staff, Somoza said that if the U.S. gave him the arms, he would "clean up Guatemala."[58] The proposal did not receive much immediate support, but Truman instructed the CIA to follow up on it. The CIA contacted Carlos Castillo Armas, the Guatemalan army officer who had been exiled from the country in 1949 following a failed coup attempt against the president.[59] In the belief that Armas would lead a coup with or without CIA assistance, the CIA created a plan to supply him with weapons and 225,000 U.S. dollars.[57]

The coup was planned in detail over the next few weeks by the CIA, the United Fruit Company, and Somoza. The CIA contacted Marcos Pérez Jiménez and Rafael Trujillo the U.S.-supported right-wing dictators of Venezuela and the Dominican Republic, respectively. The two dictators were supportive of the plan, and agreed to contribute some funding.[60] Although PBFORTUNE was officially approved on September 9, 1952, various planning steps had been taken earlier in the year. In January 1952, officers in the CIA's Directorate of Plans compiled a list of "top flight Communists whom the new government would desire to eliminate immediately in the event of a successful anti-Communist coup."[61] The CIA plan called for the assassination of over 58 Guatemalans, as well as the arrest of many others.[61]

The CIA put the plan into motion in late 1952. A freighter that had been borrowed from the United Fruit Company was specially refitted and loaded with weapons in New Orleans under the guise of agricultural machinery, and set sail for Nicaragua.[62] The State Department became aware that many details of the plan had already become public knowledge, thanks to Somoza discussing it openly with his government officials.[57] This came to the attention of Dean Acheson, the secretary of state, who called off the plot.[57] The freighter was redirected to Panama, where the arms were unloaded.[60] The CIA continued to support Castillo Armas; it granted him a retainer of 3000 U.S. dollars a month, and gave him the resources to maintain his rebel force.[57]

Operation PBSUCCESS

Genesis

In addition to the lobbying of the United Fruit Company, several other factors also led the United States to launch the coup that toppled Árbenz in 1954. The U.S. government had also grown more suspicious of the Guatemalan Revolution as the Cold War developed and the Guatemalan government clashed with U.S. corporations on an increasing number of issues.[63] The Cold War predisposed the Truman administration to see the Guatemalan government as communist.[63] Arévalo's support for the Caribbean Legion also worried the Truman administration, which saw it as a vehicle for communism, rather than as the anti-dictatorial force it was conceived as.[64] Until the end of its term, the Truman administration relied on purely diplomatic and economic means to try and reduce the communist influence.[65] The United States had refused to sell arms to the Guatemalan government after 1944; in 1951 it began to block weapons purchases by Guatemala from other countries.[66] The enactment of the agrarian reform law in 1952 provoked Truman to authorize Operation PBFORTUNE. Although this was quickly aborted, tension between the U.S. and Guatemala continued to rise, especially with the legalization of the communist Guatemalan Party of Labour and its inclusion in the government coalition for the elections of January 1953.[67] Articles published in the U.S. press often reflected this predisposition to see communist influence; for example, a New York Times article about the visit to Guatemala by Chilean poet Pablo Neruda highlighted Neruda's communist beliefs while neglecting to mention his reputation as the greatest living poet from Latin America.[68]

In November 1952, Dwight Eisenhower was elected president of the U.S. Eisenhower's campaign had included a pledge for a more active anti-communist policy, promising to rollback, rather than contain, communism. The campaign had been influenced by the rise of McCarthyism in the U.S. government, and so Eisenhower was more willing to use the CIA to remove governments the U.S. disliked.[69][70] Several figures in his administration, including Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and his brother and CIA director Allen Dulles had close ties to the United Fruit Company. The Dulles brothers had worked for the law firm of Sullivan & Cromwell, and in that capacity had arranged several deals for the UFC. Undersecretary of state Bedell Smith later became a director of the UFC, while the wife of the UFC public relations director was Eisenhower's personal assistant. These personal connections meant that the Eisenhower administration tended to conflate the interests of the UFC with U.S. national security interests, and made it more willing to overthrow the Guatemalan government.[71][72] The successful CIA operation to overthrow the democratic Iranian government also strengthened Eisenhower's belief in using the CIA to effect political change.[69]

Planning

The CIA operation to overthrow Jacobo Árbenz, code-named Operation PBSUCCESS, was authorized by Eisenhower in August 1953.[11] The operation was granted a budget of 2.7 million U.S. dollars for "psychological warfare and political action."[11] The total budget has been estimated at between 5 and 7 million dollars, and the planning employed over 100 CIA agents. In addition, the operation recruited scores of individuals from among Guatemalan exiles and the populations of the surrounding countries. The operational headquarters for the Operation was in the town of Opa-locka, Florida.[73] The plans included drawing up lists of people within Árbenz' government to be assassinated if the coup were to be carried out. Manuals of assassination techniques were compiled, and lists were also made of people whom the junta would dispose of.[11] The U.S. State department created a team of diplomats who would support PBSUCCESS. The leader of this team was John Peurifoy, who took over as the U.S. ambassador in Guatemala in October 1953,[74] an appointment which signaled the solidifying U.S. plot.[75] Peurifoy was a militant anti-communist, and had proven to be willing to work with the CIA during his previous posting in Greece.[76] Under his tenure diplomatic relations with Guatemala soured further, with the exception of relations between the U.S. government and the Guatemalan military. In a report to Dulles, Peurifoy stated that he was "definitely convinced that if [Árbenz] is not a communist, then he will certainly do until one comes along."[77] Within the CIA, the person heading the operation was CIA deputy director Frank Wisner, who had worked in the U.S. intelligence service since World War II. The field commander was U.S. army Colonel Albert Haney, who was then chief of the CIA station in South Korea. Haney reported directly to Wisner, thereby separating Operation PBSUCCESS from the CIA's Latin American division, a decision which created some tension within the agency.[78]

The CIA operation was complicated by the launch of a premature coup on 29 March 1953, when a futile raid against the Army garrison at Salamá, in the central Guatemalan department of Baja Verapaz. The rebellion was swiftly crushed, and a number of participants arrested. This incident resulted in a number of CIA agents and allies being imprisoned, weakening the coup effort. Thus the CIA came to rely more heavily on the Guatemalan exile-groups and their anti-democratic allies in Guatemala.[79] The CIA considered several candidates to lead the coup. Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes, the conservative candidate who had lost the 1950 election to Árbenz, held favor with the Guatemalan opposition but was rejected for his role in the Ubico regime, as well as his European visage, which was unlikely to appeal to the majority mixed-race mestizo population.[80] Another popular candidate was the coffee planter Juan Córdova Cerna, who had briefly served in Arévalo's cabinet before becoming the legal adviser to the UFC. The death of his son in an anti-government uprising in 1950 turned him against the government, and he had planned the small unsuccessful coup in Salamá in 1953 before fleeing to join Castillo Armas in exile. Although his status as a civilian gave him an advantage over Castillo Armas, he was diagnosed with throat cancer in 1954, taking him out of the reckoning.[81] This led to the selection of Carlos Castillo Armas, the lieutenant of Francisco Javier Arana and had been exiled following the failed coup in 1949.[81] Armas had been on the CIA payroll since the aborted Operation PBFORTUNE in 1951.[57]

Castillo Armas was given enough money to recruit a small force of approximately 150 mercenaries from among Guatemalan exiles and the populations of nearby countries. This band was called the "Army of Liberation."[82] The CIA established training camps in Nicaragua and Honduras, and supplied them with weapons as well as several bombers. Prior to the invasion of Guatemala the U.S. signed military agreements with both those countries, allowing it to move heavier arms freely. These preparations were only superficially covert: the CIA intended Árbenz to find out about them, as a part of its plan to convince the Guatemalan people that the overthrow of Árbenz was a fait accompli.[82] Additionally, the CIA made covert contact with a number of church leaders throughout the Guatemalan countryside, and persuaded them to incorporate anti-government messages into their sermons.[82]

Caracas conference and U.S. propaganda

While the preparations for Operation PBSUCCESS were being carried out, the U.S. government began a series of public statements denouncing the Guatemalan government, and alleging that it had been infiltrated by communists.[83] The U.S. State department also asked the Organization of American States to modify the agenda of the Tenth Inter-American Conference, which was scheduled to be held in Caracas in March 1954, requesting the addition of an item entitled "Intervention of International Communism in the American Republics," which was widely seen as a move targeting Guatemala.[83] In January 1954, the Guatemalan government published documents leaked to it by a member of Castillo Armas' team who had turned against him. A spate of arrests followed of allies of Castillo Armas within Guatemala, and the government issued statements implicating a "Government of the North" in a plot to overthrow Árbenz. The U.S. government denied the allegations, and the U.S. media uniformly took the side of the government; even publications which had until then provided relatively balanced coverage of Guatemala, such as the Christian Science Monitor, suggested that Árbenz had succumbed to communist propaganda. Several congressmen in the U.S. also stated that the allegations from the Guatemalan government proved that it had become communist.[84] At the conference in Caracas, the various Latin American governments sought economic aid from the U.S., while seeking to maintain the principle of non-intervention by the U.S. government in their internal affairs.[85] The aim of the U.S. government was to pass a resolution condemning the supposed spread of communism in the Western Hemisphere. The Guatemalan foreign minister Guillermo Toriello argued strongly against the resolution, stating that it represented the "internationalization of McCarthyism. Despite support among the delegates for Toriello's views, the resolution passed with only Guatemala voting against, because of the votes of dictatorships dependent on the U.S. and the threat of economic pressure applied by Dulles.[86] Although support among the delegates for Dulles' strident anti-communism was less strong than Dulles and Eisenhower had hoped for,[85] the conference represented a success for the U.S., because it had been able to make concrete Latin American views on communism.[86]

The U.S. had stopped selling arms to Guatemala in 1951 while signing bilateral defense agreements and increasing arms shipments to Honduras and Nicaragua, and promising the Guatemalan military that they too could obtain arms if Árbenz were deposed. In 1953, the State Department aggravated the American arms embargo by thwarting Árbenz Government arms purchases from Canada, Germany, and Rhodesia.[87][88] By 1954 Árbenz had become desperate for weapons, and decided to acquire them secretly from Czechoslovakia, which would have been the first time that a Soviet bloc country shipped weapons to the Americas.[89][90] The weapons were delivered to Guatemala at the Atlantic Ocean port of Puerto Barrios, by the Swedish freight ship MS Alfhem, which sailed from the port of Szczecin in the People's Republic of Poland.[90] The U.S. tried and failed to intercept the shipment despite imposing a naval quarantine on Guatemala, which violated international law at the time.[91] In the words of the New York Times, the weapons were "worthless military junk".[92] The shipment of these weapons was portrayed by the CIA as Soviet interference in the United States' backyard, and acted as the final spur for the CIA to launch its coup.[90]

U.S. rhetoric abroad also had an effect on the Guatemalan military. The military had always been anti-communist, and John Peurifoy had been applying a lot of pressure to high-ranking officers since his arrival in Guatemala in October 1953.[93] Árbenz had intended the shipment of weapons from the Alfhem to be used to bolster peasant militia, in the event of army disloyalty, but the U.S. informed the Guatemalan army chiefs of the shipment, forcing Árbenz to hand them over to the military, and deepening the rift between him and the chiefs of his army.[93]

Castillo Armas' invasion

Castillo Armas' force of 480 men had been split into four teams, ranging in size from 198 to 60. On 15 June 1954 these four forces left their bases in Honduras and El Salvador, and assembled in various towns just outside the Guatemalan border. The largest force was supposed to attack the Atlantic harbor town of Puerto Barrios, while the others attacked the smaller towns of Esquipulas, Jutiapa, and Zacapa, the Guatemalan army's largest frontier post.[94] The invasion plan quickly faced difficulties; the 60-man force was intercepted and jailed by Salvadoran policeman before it got to the border.[94] At 8:20 am on 18 June 1954, Castillo Armas led his invading troops over the border. Ten trained saboteurs preceded the invasion, with the aim of blowing up railways and cutting telegraph lines. At about the same time, Castillo Armas' planes flew over a pro-government rally in the capital.[94] Castillo Armas' demanded Árbenz' immediate surrender.[95] The invasion provoked a brief panic in the capital, which quickly decreased as the rebels failed to make any striking moves. Bogged down by supplies and a lack of transportation, Castillo Armas' forces took several days to reach their targets, although their planes blew up a bridge on 19 June.[94]

When the rebels did reach their targets, they met with further setbacks. The force of 122 men targeting Zacapa were intercepted and decisively beaten by a small garrison of 30 Guatemalan soldiers, with only 30 rebels escaping death or capture.[96] The force that attacked Puerto Barrios was dispatched by policemen and armed dockworkers, with many of the rebels fleeing back to Honduras. In an effort to regain momentum, the rebel planes tried air attacks on the capital.[96] These attacks caused little material damage, but they had a significant psychological impact, leading many citizens to believe that the invasion force was more powerful than it actuality was. The rebel bombers needed to fly out of the Nicaraguan capital of Managua; as a result, they had a limited payload. A large number of them substituted dynamite or Molotov cocktails for bombs, in an effort to create loud bangs with a lower payload.[97] The planes targeted ammunition depots, parade grounds, and other visible targets. Early in the morning of 27 June 1954, a CIA Lockheed P-38M Lightning attacked Puerto San José and dropped napalm bombs on the British cargo ship, SS Springfjord, on charter to the U.S. company W.R. Grace and Company Line, which was being loaded with Guatemalan cotton and coffee.[98] This incident cost the CIA one million U.S. dollars in compensation.[97] On 22 June, another rebel plane bombed the Honduran town of San Pedro de Copán; Dulles claimed the attack had been by the Guatemalan air force, thus avoiding diplomatic consequences.[99] The handful of bombers that the rebel forces had begun with were shot down by the Guatemalan army within a few days, causing Castillo Armas to demand more from the CIA. Eisenhower quickly agreed to provide these additional planes, bolstering the rebel force.[100]

Psychological warfare

Castillo Armas' army of 480 men was not large enough to defeat the Guatemalan military, even with U.S. supplied planes. Therefore, the plans for Operation PBSUCCESS called for a campaign of psychological warfare, which would present Castillo Armas' victory as a fait accompli to the Guatemalan people, and would force Árbenz to resign.[11][101] The U.S. propaganda campaign had begun well before the invasion, with the USIA writing hundreds of articles on Guatemala based on CIA reports, and distributing tens of thousands of leaflets throughout Latin America. The CIA persuaded the governments that were friendly to it to screen video footage of Guatemala that supported the U.S. version of events. [102]

The success of the Alfhem in evading the U.S. effort to stop it led to the U.S. escalating its intimidation of Guatemala through the use of its navy. On 24 May, the U.S. launched Operation HARDROCK BAKER, a naval blockade of Guatemala. Ships and submarines patrolled the Guatemalan coasts, and all approaching ships were stopped and searched. This included ships from Britain and France, which was a violation of international law at the time.[103] Britain and France did not protest very strongly, in the hope that the U.S. would not interfere with their efforts to subdue rebellious colonies in the Middle East.[103] The intimidation was not solely naval; on 26 May one of Castillo Armas planes flew over the capital, dropping leaflets that exhorted people to struggle against communism and support Castillo Armas.[103]

The most wide-reaching psychological weapon was the radio station known as the "Voice of Liberation." This station began broadcasting on 1 May 1954, carrying anti-communist messages, telling its listeners to resist the Árbenz government and support the liberating forces of Castillo Armas.[104] The station claimed to be broadcasting from deep within the jungles of the Guatemalan hinterland, a message which many listeners chose to believe. In actuality, the broadcasts were concocted in Miami by Guatemalan exiles, flown to Central America, and broadcast through a mobile transmitter.[104] The station made an initial broadcast that was repeated four times, after which it took to transmitting two-hour bulletins twice a day. The transmissions were initially only heard intermittently in Guatemala City; a week later, the CIA significantly increased their transmitting power, allowing clear reception in the Guatemalan capital.[104] The radio broadcasts have been given a lot of credit by historians for the success of the coup, due to the unrest they created through the country. They were unexpectedly assisted by the outage of the government-run radio station, which stopped transmitting for three weeks while a new antenna was being fitted.[104] These transmissions continued throughout the conflict, broadcasting news of rebel troops converging on the capital, and contributing to massive demoralization among both the army and the civilian population.[105]

Guatemalan response

The Árbenz Government originally meant to repel the invasion by arming the military-age populace, the workers' militia, and the Guatemalan Army. Resistance from the armed forces, as well as public knowledge of the secret arms purchase, compelled the President to supply arms only to the Army.[98] From the beginning of the invasion Árbenz was confident that Castillo Armas could be defeated militarily, and expressed this confidence in public.[106] He was worried that a defeat for Castillo Armas would provoke a U.S. invasion. This also contributed to his decision not to arm civilians initially; lacking a military reason to do so, this could have cost him the support of the army.[106] Carlos Enrique Díaz, the chief of the Guatemalan armed forces, also told Árbenz that arming the civilians would be unpopular within the army, and that "the army [would] do its duty."[106]

Árbenz instead told Díaz to select officers to lead a counter-attack. Díaz chose a corps of officers who were all known to be men of personal integrity, and who were loyal to Árbenz.[106] On the night of 19 June, most of the Guatemalan troops in the capital region left for Zacapa, joined by smaller detachments from other garrisons.[107] Árbenz stated that "the invasion was a farce." He worried that if it was defeated on the Honduran border, Honduras would use it as an excuse to declare war on Guatemala, which would lead to a U.S. invasion.[107] Due to the rumours spread by the Voice of Liberation, peasants throughout the countryside were worried that a fifth column attack was imminent, and so large numbers went to the government and asked for weapons to defend their country. They were repeatedly told that the army was "successfully defending our country."[107] Nonetheless, peasant volunteers assisted the government war effort, manning roadblocks and donating supplies to the army. Weapons shipments dropped by rebel planes were intercepted and turned over to the government.[107]

The Árbenz government also pursued diplomatic means to try and end the invasion. It sought support from El Salvador and Mexico; Mexico declined to get involved, and the Salvadoran government merely reported the Guatemalan effort to John Peurifoy.[108] Árbenz' largest diplomatic initiative was in taking the issue to the United Nations Security Council. On 18 June the Guatemalan foreign minister petitioned the Council to "take measures necessary...to put a stop to the aggression," which he said Nicaragua and Honduras were responsible for, along with "certain foreign monopolies which have been affected by the progressive policy of my government."[108] The security council looked at Guatemala's complaint at an emergency session on20 June. The debate was lengthy and heated, with Nicaragua and Honduras denying any wrongdoing, and the U.S. stating that Eisenhower's role as a general in World War II demonstrated that he was against imperialism.[109] The Soviet Union was the only country to support Guatemala. When the U.S. and its allies proposed referring the matter to the Organization of American States, the USSR vetoed the proposal.[109] Guatemala continued to press for a Security Council investigation, a proposal that received the support of Britain and France. On 24 June the U.S. vetoed the proposal, exercising its veto against its allies for the first time in United Nations history.[109] The U.S. accompanied this with threats to the foreign offices of both countries that the U.S. would stop supporting their other initiatives.[109] United Nations Secretary General Dag Hammarskjöld called the U.S. position "the most serious blow so far aimed at the [United Nations]."[110] A fact-finding mission was set up by the Inter-American Peace Committee; the United States used its influence to delay the entry of the committee until the coup was complete and the military dictatorship installed.[109]

Árbenz' resignation

Árbenz was initially confident that his army would quickly dispatch the rebel force. The victory of a small garrison of 30 soldiers over the 180 strong rebel force outside Zacapa strengthened his belief.[108] By 21 June, Guatemalan soldiers had gathered at Zacapa under the command of Colonel Víctor M. León, who was believed to be loyal to Árbenz. León reported to Árbenz that the counter-attack would be delayed due to logistical reasons, but stated that this was not reason to worry, and that Castillo Armas would be defeated very soon.[108] Other members of the government were not so certain. Army Chief of Staff Parinello inspected the troops at Zacapa on 23 June, and returned to the capital believing that the army would not fight. Afraid of a U.S. intervention in Castillo Armas' favor, he did not tell Árbenz of his suspicions.[108] The leaders of the communist party also began to have their suspicions. Alvarado Monzón, the acting secretary general of the PGT, sent a member of the central committee to Zacapa to investigate. He returned on 25 June, reporting that the army was highly demoralized, and would not fight.[111][112] Monzón reported this to Árbenz, who quickly sent another investigator. He, too, returned the same report; additionally, he brought a message back to Árbenz from the officers at Zacapa, asking Árbenz to resign. The officers believed that given U.S. support for the rebels, defeat was inevitable, and Árbenz was to blame for it.[112] He stated that if Árbenz did not resign, the army was likely to strike a deal with Castillo Armas, and march on the capital with him.[112][111]

During this period, Castillo Armas had begun to intensify his aerial attacks, with the extra planes that Eisenhower had approved. They had limited material success; many of their bombs were surplus material from World War II, and failed to explode. Nonetheless, they had a significant psychological impact.[113] On 25 June, the same day that he received the army's ultimatum, Árbenz learned that Castillo Armas had scored what later proved to be his only military victory, defeating the Guatemalan garrison at Chiquimula.[112] Historian Piero Gleijeses has stated that if it were not for U.S. support for the rebellion, the officer corps of the Guatemalan army would have remained loyal to Árbenz because, although they were not uniformly his supporters, they were more wary of Castillo Armas, and also had strong nationalist views. As it was, they believed that the U.S. would intervene militarily, leading to a battle they could not win.[112]

On the night of 25 June, Árbenz called a meeting of the senior leaders of the government, the political parties, and the labor unions. Colonel Díaz was also present.[114] The President told them that the army at Zacapa had abandoned the government, and that the civilian population needed to be armed in order to defend the country.[114] Díaz raised no objections, and the unions pledged several thousand troops between them.[114][105] When the troops were mustered the next day, only a few hundred showed up.[114][105] The civilian population of the capital had fought alongside the Guatemalan Revolution twice before; during the popular uprising of 1944, and again during the attempted coup of 1949. On both those occasions some of the army had fought alongside the citizenry; intimidated by the United States, the army refused to fight on this occasion, and the union members were reluctant to fight both the invasion and their own military.[114][105] Seeing this, Díaz reneged on his support of the president, and began plotting to overthrow Árbenz with the assistance of other senior army officers. They informed Peurifoy of this plan, asking him to stop the hostilities in return for Árbenz' resignation.[115] Peurifoy promised to arrange a truce, and the plotters went to Árbenz and informed him of their decision. Árbenz, utterly exhausted and seeking to preserve at least a measure of the democratic reforms that he had brought, agreed without demur. After informing his cabinet of his decision, he left the presidential palace at 8 pm on 27 June 1954, having taped a resignation speech that was broadcast an hour later.[115] In it, he stated that he was resigning in order to eliminate the "pretext for the invasion," and that he wished to preserve the gains of the October Revolution.[115] He walked to the nearby Mexican Embassy, seeking political asylum.[116] Two months later he was granted safe conduct out of the country, and flew to exile in Mexico.[117]

Military governments

Immediately after the President announced his resignation, Díaz announced on the radio that he was taking over the presidency, and that the army would continue to fight against the invasion of Castillo Armas.[118] Two days later Peurifoy told Díaz that he had to resign because, in the words of the CIA officer who spoke to Díaz, he was "not convenient for American foreign policy."[119][120] Peurifoy castigated Díaz for allowing Árbenz to criticize the United States in his resignation speech; meanwhile, a U.S.-trained pilot dropped a bomb on the army's main powder magazine, in order to intimidate the colonel.[121] Díaz initially attempted to placate Peurifoy by forming a three-person junta, which he led; Peurifoy continued to insist that Díaz resign, and he was overthrown by a rapid bloodless coup led by Elfego Hernán Monzón Aguirre, a more pliable army colonel.[119] Díaz later stated that Peurifoy had presented him with a list of names, and demanded that all of them be shot by the next day, because they were communists; Díaz had refused, turning Peurifoy further against him.[122] On 17 June, the army leaders at Zacapa had begun to negotiate with Castillo Armas. They signed a pact, known as the Pacto de Las Tunas, three days later, which placed the army at Zacapa under Castillo Armas, in return for a general amnesty.[119] The army returned to its barracks a few days later, "despondent, with a terrible sense of defeat."[119]

Although Monzón was staunchly anti-communist and repeatedly spoke of his loyalty to the U.S., he was unwilling to hand over power to Castillo Armas.[119] The fall of Díaz had led Peurifoy to believe that the CIA should make way and let the U.S. State Department play the lead role in negotiating with the new government of Guatemala.[123] The State Department asked Óscar Osorio, the dictator of El Salvador, to invite all players to talk in San Salvador. Osorio agreed, and Monzón and Castillo Armas arrived in the Salvadoran capital on 30 June.[119] Peurifoy initially remained in Guatemala City, to avoid the appearance of a heavy U.S. role; he was forced to travel to San Salvador when the negotiations came close to breaking down on the first day.[119][124] In the words of Dulles, Peurifoy's role was to "crack some heads together."[124] Neither Monzón nor Castillo Armas could have remained in power without U.S. support, and thus Peurifoy was able to force an agreement, which was announced at 4:45 am on 2 July. Under the agreement, Castillo Armas and his subordinate Major Enrique Trinidad Oliva joined the three person junta headed by Monzón, with Monzón remaining president.[119] On 7 July Colonels Dubois and Cruz Salazar, Monzón's supporters on the junta, resigned, according to the secret agreement they had made without Monzón's knowledge. Outnumbered, Monzón also resigned, allowing Castillo Armas to be unanimously elected president of the junta.[119] The two colonels were paid 100,000 U.S. dollars apiece for their cooperation.[119] The U.S. promptly recognized the new government on 13 July.[125] Elections were held in early October, from which all political parties were barred from participating. Castillo Armas was the only candidate; he won the election with 99% of the vote, completing his transition into power.[126][127]

Reactions

The Guatemalan coup d'état was reviled internationally, with the French and British press, Le Monde and The Times, attacking the United States' coup as a "modern form of economic colonialism". In Latin America, public and official opinions expressed much political criticism of the U.S., and Guatemala became symbolic to many of armed resistance to the perceived U.S. hegemony over Latin America.[11] British Prime Minister Clement Attlee called it "a plain act of aggression."[128] The Secretary General of the United Nations, Dag Hammarskjöld (1953–61), said that the paramilitary invasion with which the U.S. deposed the elected government of Guatemala was a geopolitical action that violated the human rights stipulations of the UN Charter. Even the usually pro–U.S. newspapers of West Germany condemned the Guatemalan coup d'état. Kate Doyle, the Director of the Mexico Project of the National Security Archives, said that the 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état was the definitive deathblow to democracy in the Republic of Guatemala.[11] The coup had broad support among politicians in the United States. Historian Piero Gleijeses writes that the foreign policy of both major U.S. political parties had consisted of an intransigent assertion of U.S. hegemony over Central America, making it predisposed to seeing a communist threat where none existed.[129] Thus Eisenhower's continuation of the Monroe Doctrine had continued bipartisan support.[129] The coup met with strong negative reactions in Latin America; a wave of anti-United States protests followed the overthrow of Árbenz. These sentiments persisted for several decades afterwards; historians have pointed to the coup as a reason for the hostile reception given to U.S. Vice President Richard Nixon when he visited Latin America four years later.[130] A State Department study found that negative public reactions to the coup had occurred in eleven Latin American countries, including a few that were otherwise pro-American.[131]

Operation PBHISTORY

Operation PBHISTORY was an effort by the CIA to analyze documents from the Árbenz government to justify the 1954 coup after the fact.[132] Due to the quick overthrow of the Árbenz government, the CIA believed that the government would not have been able to destroy any incriminating documents, and that these could be analyzed to demonstrate Árbenz' supposed ties to the Soviet Union.[133] The CIA also believed that it could better understand the workings of Latin American communist parties, on which subject the CIA had very little real information.[133] A final motivation was that international responses to the coup had been very negative, even among allies of the U.S., and the CIA wished to counteract the anti-U.S. sentiment.[134] The operation began on 4 July 1954 with the arrival of four CIA agents in Guatemala City, led by a specialist in the structure of communist parties. Targets included Árbenz' personal belongings, police documents, and the headquarters of the Guatemalan Party of Labour.[135] Although the initial search failed to find any links to the Soviet Union, the CIA decided to extend the operation, and on 4 August a much larger team was deployed, with members from many government departments, including the state department and the U.S. information agency. The task force was given the cover name "Social Research Group."[136] In order to avoid confrontation with Guatemalan nationalists, the CIA opted to leave the documents in Guatemalan possession, instead funding the creation of a Guatemalan intelligence agency that would try to dismantle the communist organizations. The Comite' de Defensa Nacional Contra el Comunismo (National Committee for Defense against Communism) was created on 20 July, and granted a great deal of power over military and police functions.[137] The personnel of the new agency were also put to work analyzing the same documents.[138]

The document processing phase of the operation was terminated on 28 September 1954, having examined 500,000 documents.[138] There was tension between the different U.S. government agencies about using the information; the CIA wished to use it to subvert communists, whereas USIA wished to use it for propaganda. The CIA's leadership of the operation allowed it to retain control over any documents deemed necessary for clandestine operations.[139] A consequence of PBHISTORY was the opening of a CIA file on Ernesto Che Guevara.[140] In the subsequent decade, the documents gathered were used by the authors of several books, most frequently with covert CIA assistance, which described the Guatemalan Revolution and the 1954 coup in terms favorable to the CIA.[141] Despite the efforts of the CIA, both international and academic reaction to U.S. policy remained highly negative. Even books partially funded by the CIA were somewhat critical of the role played by the CIA. PBHISTORY failed in its chief objective; finding convincing evidence that Guatemalan communists had been instruments of the Soviet Union,[142] and found scant evidence of any connection to Moscow whatsoever.[143] The Soviet description of the coup, that the U.S.A. had crushed a democratic revolution to protect the United Fruit Company's control over the Guatemalan economy, became much more widely accepted.[144]

Aftermath

Political legacy

The 1954 coup had a large political fallout both inside and outside Guatemala. The relatively easy overthrow of Árbenz, coming soon after the similar overthrow of the democratically elected Iranian Prime Minister in 1953, made the CIA overconfident in its abilities, which led to the Bay of Pigs disaster in 1961.[145][146] Among the civilians living in Guatemala City during the coup was a twenty-five-year-old Ernesto Che Guevara. After a couple of abortive attempts to fight on the side of the government, Guevara took shelter at the embassy of Argentina, before eventually being granted safe passage to Mexico, where he would join the Cuban Revolution. His experience of the Guatemalan coup was a large factor in convincing him "of the necessity for armed struggle...against imperialism", and would inform his successful military strategy during the Cuban Revolution.[147] Árbenz' experience during the Guatemalan coup also helped Fidel Castro's Cuban regime in thwarting the CIA invasion.[148] Throughout the years of the Guatemalan Revolution, both United States policy makers and the U.S. media had tended to believe the theory of a communist threat. When Árbenz had announced evidence of U.S. complicity in the Salama incident, it had been dismissed, and virtually the entire U.S. press portrayed Castillo Armas invasion as a dramatic victory against communism.[149] The press in Latin America were less restrained in their criticism of the U.S., and the coup resulted in lasting anti-United States sentiment in the region.[150][151]

Within Guatemala, Castillo Armas worried that he lacked popular support, and thus tried to eliminate all opposition. He promptly arrested several thousand opposition leaders, branding them communists, repealed the constitution of 1945, and granted himself virtually unbridled power.[152] Concentration camps were built to hold the prisoners when the jails overflowed. Acting on the advice of Dulles, Castillo Armas also detained a number of citizens trying to flee the country. He also created a National Committee of Defense Against Communism, with sweeping powers of arrest, detention, and deportation. Over the next few years, the committee investigated nearly 70,000 people. Many were imprisoned, executed, or "disappeared", frequently without trial.[152] He outlawed all political parties, labor unions, and peasant organizations.[153] Castillo Armas' dependence on the officer corps and the merceneries who had put him in power led to widespread corruption, and the Eisenhower administration was soon subsidizing the Guatemalan government with many millions of U.S. dollars.[154] Castillo Armas also reversed the agrarian reforms of Árbenz, leading the U.S. embassy to comment that it was a "long step backwards" from the previous policy.[155] The United Fruit Company also did not profit from the coup; despite regaining most of its privileges, its profits continued to decline, and it was eventually merged with another company to save itself from bankruptcy.[156]

Civil War in Guatemala

The rolling-back of the progressive policies of the civilian governments resulted in a series of leftist insurgencies in the countryside, beginning in 1960.[157] This triggered the thirty-six-year Guatemalan Civil War, between the U.S.-backed military government of Guatemala and the leftist insurgencies, which frequently had a large degree of popular support.[157] The largest of these movements was led by the Guerrilla Army of the Poor, which at its largest point had 270,000 members.[157] The civil war ran from 1960 to 1996. By the end of it 200,000 civilians were dead.[157] During the civil war, atrocities against civilians were committed by both sides; 93% of these violations were committed by the United States-backed military,[157][158][159][160] which included a genocidal scorched-earth campaign against the indigenous Maya population in the 1980s.[157] The violence was particularly brutal during the presidencies of Ríos Montt and Lucas García.[161] Numerous other human rights violations were committed, including massacres of civilian populations, rape,[162] aerial bombardment, and forced disappearances,[157] leading Gleijeses to write that Guatemala was "ruled by a culture of fear," and that it held the "macabre record for human rights violations in Latin America."[163] These violations were partially the result of a particularly brutal counter-insurgency strategy adopted by the government.[161][157] The civil war came to an end in 1996, with a peace accord between the guerrillas and the government of Guatemala, which included an amnesty for all the fighters, both among the military and the guerrillas.[161]

Apologies

In March 1999, US President Bill Clinton apologized to the Guatemalan government for the atrocities committed by the US-backed dictatorships.[164]

In October 2011, the government of Guatemala formally apologized to Juan Jacobo Árbenz, the son of the deposed President, Jacobo Árbenz. At the same time, the textbooks used in the public school system were revised to portray Árbenz in a positive light, depicting him as a Guatemalan patriot. A highway was also renamed in his honor. The Árbenz family continue to request an apology from the government of the United States for having overthrown the government of Guatemala in 1954.[165]

See also

- Banana republic

- CIA activities in the Americas

- Covert U.S. regime change actions

- Guatemalan Civil War

- Guatemalan Revolution

- History of Guatemala

- John Peurifoy

- National Committee of Defense Against Communism

- Operation Kufire

- Operation Kugown

- Operation PBFORTUNE

- Operation PBHISTORY

- Operation WASHTUB

- Plausible deniability

Notes and references

References

- ↑ Gleijeses 1991, pp. 1–5.

- 1 2 3 4 Streeter 2000, pp. 11–12.

- 1 2 Immerman 1982, pp. 34–37.

- 1 2 Cullather 2006, pp. 9–10.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, pp. 41–43.

- 1 2 3 Streeter 2000, pp. 12–13.

- 1 2 Streeter 2000, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, pp. 48–50.

- ↑ Paterson 2009, p. 304.

- ↑ May 1999, pp. 58–91.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kornbluh 1997.

- 1 2 Streeter 2000, p. 8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gilderhus 2006.

- ↑ LaFeber 1993, p. 34.

- 1 2 3 Streeter 2000, pp. 8–10.

- ↑ Smith 1995, p. 6.

- 1 2 Forster 2001, pp. 12–15.

- 1 2 Gleijeses 1991, pp. 10–11.

- ↑ Chapman 2008, p. 83.

- 1 2 William Blum (2003). Killing Hope: US Military and CIA Interventions Since World War II. Gospons Papers Limited. p. 75.

- ↑ LaFeber 1993, pp. 76–77.

- ↑ LaFeber 1993, p. 77.

- 1 2 Streeter 2000, pp. 10–11.

- 1 2 Forster 2001, p. 29.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1991, p. 13.

- ↑ LaFeber 1993, p. 79.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1991, p. 20.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1991, p. 22.

- 1 2 3 Streeter 2000, p. 12.

- ↑ Streeter 2000, p. 11-12.

- 1 2 Streeter 2000, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Forster 2001, pp. 98–99.

- ↑ Forster 2001, pp. 99–101.

- ↑ Streeter 2000, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Streeter 2000, pp. 16–17.

- 1 2 Gleijeses 1991, pp. 73–84.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ Streeter 2000, pp. 18–19.

- 1 2 3 Immerman 1982, pp. 64–67.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1991, pp. 144–146.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Gleijeses 1991, pp. 149–164.

- ↑ Grandin 2000, pp. 200–201.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, pp. 68–70.

- ↑ Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, pp. 65–68.

- 1 2 3 Immerman 1982, pp. 68–72.

- 1 2 3 Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, pp. 67–71.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, pp. 73-76.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, pp. 73–76.

- ↑ Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, p. 71.

- 1 2 3 Immerman 1982, pp. 75–82.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, p. 72-77.

- ↑ Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, pp. 78–90.

- 1 2 3 Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, pp. 90–97.

- 1 2 Cullather 2006, pp. 14–28.

- ↑ Cullather 2006, p. 18-19.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1991, p. 228.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cullather 2006, pp. 28–35.

- 1 2 Gleijeses 1991, pp. 228–229.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1991, pp. 59–69.

- 1 2 Gleijeses 1991, pp. 229–230.

- 1 2 Haines 1995.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1991, p. 230.

- 1 2 Immerman 1982, pp. 82–100.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, p. 95.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, pp. 109–110.

- ↑ Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, p. 102.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1991, p. 231.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, p. 96.

- 1 2 Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, pp. 100–101.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1991, p. 234.

- ↑ Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, pp. 106–107.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, pp. 122–127.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, pp. 138–143.

- ↑ Cullather 2006, p. 45.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, p. 137.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1991, pp. 251–254.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1991, p. 255.

- ↑ Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, pp. 108–109.

- ↑ Cullather 1994, p. 21.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, pp. 141–142.

- 1 2 Immerman 1982, pp. 141–143.

- 1 2 3 Immerman 1982, pp. 162–165.

- 1 2 Gleijeses 1991, pp. 256–257.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1991, pp. 259–262.

- 1 2 Gleijeses 1991, pp. 267–278.

- 1 2 Immerman 1982, pp. 146–150.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, pp. 144–150.

- ↑ Cullather 1994, p. 36.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1991, pp. 280–285.

- 1 2 3 Immerman 1982, pp. 155–160.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1991, pp. 310–316.

- ↑ William Blum (2003). Killing Hope: US Military and CIA Interventions Since World War II. Gospons Papers Limited. p. 73.

- 1 2 Gleijeses 1991, pp. 300–311.

- 1 2 3 4 Cullather 2006, pp. 87–89.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, p. 161.

- 1 2 Cullather 2006, pp. 90–93.

- 1 2 Immerman 1982, pp. 166–167.

- 1 2 Gordon 1971.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1991, p. 340.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, pp. 168–169.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, p. 165.

- ↑ Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, p. 166.

- 1 2 3 Cullather 2006, pp. 82–83.

- 1 2 3 4 Cullather 2006, pp. 74–77.

- 1 2 3 4 Cullather 2006, pp. 100–101.

- 1 2 3 4 Gleijeses 1991, pp. 320–323.

- 1 2 3 4 Gleijeses 1991, pp. 323–326.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gleijeses 1991, pp. 326–329.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Immerman 1982, pp. 169–172.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1991, p. 331.

- 1 2 Cullather 2006, p. 97.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gleijeses 1991, pp. 330–335.

- ↑ Cullather 2006, pp. 98–100.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gleijeses 1991, pp. 342–345.

- 1 2 3 Gleijeses 1991, pp. 345–349.

- ↑ Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, p. 201.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1991, p. 390.

- ↑ Cullather 2006, pp. 102–105.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Gleijeses 1991, pp. 354–357.

- ↑ Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, p. 206.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, p. 175.

- ↑ Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, pp. 207–208.

- ↑ Cullather 2006, p. 102.

- 1 2 Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, pp. 212–215.

- ↑ Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, p. 216.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, pp. 173–178.

- ↑ Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, pp. 224–225.

- ↑ Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, p. 217.

- 1 2 Gleijeses 1991, pp. 361–170.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1991, p. 371.

- ↑ Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, p. 189.

- ↑ Holland 2004, p. 300.

- 1 2 Holland 2004, pp. 301–302.

- ↑ Holland 2004, pp. 302–303.

- ↑ Holland 2004, pp. 302–305.

- ↑ Holland 2004, p. 305.

- ↑ Holland 2004, p. 306.

- 1 2 Holland 2004, p. 307.

- ↑ Holland 2004, p. 308.

- ↑ Holland 2004, p. 309.

- ↑ Holland 2004, pp. 318–320.

- ↑ Holland 2004, pp. 321–324.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, p. 185.

- ↑ Holland 2004, p. 322.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1991, pp. 370–377.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, pp. 189–190.

- ↑ Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, pp. 184–185.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, pp. 194–195.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1991, pp. 366–370.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1991, pp. 370–371.

- ↑ Cullather 2006, p. 112.

- 1 2 Immerman 1982, pp. 198–201.

- ↑ Cullather 2006, p. 113.

- ↑ Cullather 2006, pp. 114–115.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1991, p. 382.

- ↑ Cullather 2006, pp. 118–119.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 McAllister 2010.

- ↑ Alexander Mikaberidze (2013). Atrocities, Massacres, and War Crimes: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, LLC. p. 216.

- ↑ Jennifer Harbury (2005). Truth, Torture, and the American Way: The History and Consequences of U.S Involvement in Torture. Beacon Press. p. 35.

- ↑ Leslie Alan Horvitz, Christopher Catherwood (2006). Encyclopedia of War Crimes and Genocide. Facts On File Inc. p. 183.

- 1 2 3 May 1999, pp. 68–91.

- ↑ Paul R. Bartrop, Steven Leonard Jacobs (2015). Modern Genocide: The Definitive Resource and Document Collection. ABC-CLIO. p. 963.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1991, p. 383.

- ↑ John M. Broder, Clinton Offers His Apologies To Guatemala, The New York Times, March 11, 1999

- ↑ Malkin 2011.

Sources

- Chapman, Peter (2008). Bananas!: How The United Fruit Company Shaped the World. Canongate Books. ISBN 1-84195-881-6.

- Cullather, Nicholas (1994). Operation PBSUCCESS: The United States and Guatemala, 1952–1954.

- Cullather, Nicholas (2006). Secret History: The CIA's classified account of its operations in Guatemala, 1952–1954. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-5468-2.

- Forster, Cindy (2001). The time of freedom: campesino workers in Guatemala's October Revolution. University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 978-0-8229-4162-0.

- Gilderhus, Mark T. (March 2006). "The Monroe Doctrine: Meanings and Implications". Presidential Studies Quarterly 36 (1): 5–16. doi:10.1111/j.1741-5705.2006.00282.x.

- Gleijeses, Piero (1991). Shattered Hope: The Guatemalan Revolution and the United States, 1944–1954. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02556-8.

- Gordon, Max (Summer 1971). "A Case History of U. S. Subversion: Guatemala, 1954". Science and Society 35 (2).

- Grandin, Greg (2000). The blood of Guatemala: a history of race and nation. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-2495-9.

- Haines, Gerald (June 1995). "CIA and Guatemala Assassination Proposals, 1952–1954" (PDF). CIA Historical Review Program.

- Holland, Max (2004). "Operation PBHISTORY: The Aftermath of SUCCESS". International Journal of Intelligence and Counter-Intelligence 17 (2): 300–332. doi:10.1080/08850600490274935.

- Immerman, Richard H. (1982). The CIA in Guatemala: The Foreign Policy of Intervention. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Kornbluh, Peter; Doyle, Kate, eds. (May 23, 1997) [1994], "CIA and Assassinations: The Guatemala 1954 Documents", National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 4 (Washington, D.C.: National Security Archive)

- LaFeber, Walter (1993). Inevitable Revolutions: The United States in Central America. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-03434-8.

- May, Rachel (March 1999). ""Surviving All Changes is Your Destiny": Violence and Popular Movements in Guatemala". Latin American Perspectives 26 (2): 68–91. doi:10.1177/0094582x9902600204.

- Malkin, Elisabeth (20 October 2011). "An Apology for a Guatemalan Coup, 57 Years Later". The New York Times.

- McAllister, Carlota (2010). "A Headlong Rush into the Future". In Grandin, Greg; Joseph, Gilbert. A Century of Revolution. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. pp. 276–309. ISBN 9780822392859. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- Paterson, Thomas G. (2009). American Foreign Relations: A History, Volume 2: Since 1895. Cengage Learning. ISBN 0547225695.

- Schlesinger, Stephen; Kinzer, Stephen (1999). Bitter Fruit: The Story of the American Coup in Guatemala. David Rockefeller Center series on Latin American studies, Harvard University. ISBN 9780674019300.

- Smith, Gaddis (30 November 1995). The Last Years of the Monroe Doctrine, 1945–1993. Macmillan. ISBN 9780809015689.

- Streeter, Stephen M. (2000). Managing the Counterrevolution: The United States and Guatemala, 1954–1961. Ohio University Press. ISBN 9780896802155.

Further reading

- Handy, Jim (1994). Revolution in the Countryside: Rural Conflict and Agrarian Reform in Guatemala 1944–54. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-4438-1.

- Shea, Maureen E (2001). Standish, Peter, ed. Culture and Customs of Guatemala. Culture and Customs of Latin American and the Caribbean. London: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-30596-X.

- Shillington, John (2002). Grappling with Atrocity: Guatemalan Theater in the 1990s. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-3930-6.

External links

- CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room – CIA's declassified documents on Guatemala CIA Documents Chronicling the 1954 Coup

- US State Dept. site – Foreign Relations, 1952–1954: Guatemala

- American Accountability Project at the Wayback Machine (archived October 30, 2005) – The Guatemala Genocide

- Guatemala Documentation Project – Provided by the National Security Archive.

- Video: Devils Don't Dream! Analysis of the CIA-sponsored 1954 coup in Guatemala.

- The Guatemala 1954 Documents

- From Árbenz to Zelaya: Chiquita in Latin America – video report by Democracy Now!

- The short film U.S. Warns Russia to Keep Hands off in Guatemala Crisis (1955) is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- U.S. Congressional involvement in the coup

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||