1933 Outer Banks hurricane

| Category 4 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

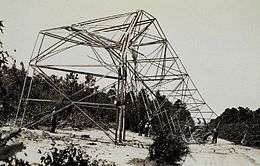

Wind damage in North Carolina from the hurricane | |

| Formed | September 8, 1933 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated |

September 22, 1933 (extratropical after September 18) |

| Highest winds |

1-minute sustained: 140 mph (220 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 947 mbar (hPa); 27.96 inHg |

| Fatalities | Over 24 reported, 2 missing |

| Damage | $4.75 million (1933 USD) |

| Areas affected | Outer Banks of North Carolina, Tidewater Virginia, New England, Nova Scotia |

| Part of the 1933 Atlantic hurricane season | |

The 1933 Outer Banks hurricane lashed portions of the North Carolina and Virginia coasts less than a month after another hurricane hit the general area. The twelfth tropical storm and sixth hurricane of the 1933 Atlantic hurricane season, it formed by September 8 to the east of the Lesser Antilles. It moved generally to the north-northwest and strengthened quickly to peak winds of 140 mph (220 km/h) on September 12. This made it a major hurricane and a Category 4 on the Saffir-Simpson scale.[nb 1] The hurricane remained at or near that intensity for several days while tracking to the northwest. It weakened approaching the southeastern United States, and on September 16 passed just east of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina with winds of about 100 mph (160 km/h). Turning to the northeast, the hurricane became extratropical on September 18 before moving across Atlantic Canada, eventually dissipating four days later.

The threat of the hurricane prompted widespread tropical cyclone warnings and watches along the eastern United States and prompted some people to evacuate. Damage was heaviest in southeastern North Carolina near New Bern, where the combination of high tides and swollen rivers flooded much of the town. Across North Carolina, the hurricane caused power outages, washed out roads, and damaged crops. Several houses were damaged, leaving about 1,000 people homeless. Damage was estimated at $4.5 million,[nb 2] and there were 21 deaths in the state, mostly from drowning. Hurricane force winds extended into southeastern Virginia, where there were two deaths. High tides isolated a lighthouse near Norfolk and covered several roads. Farther north, two people on a small boat were left missing in Maine, and another person was presumed killed when his boat sank in Nova Scotia.

Meteorological history

Beginning on September 7, there was an area of disturbed weather near and east of the Lesser Antilles,[3] by which time there was a nearly closed circulation. At 0800 UTC the next day, a ship reported winds of about 35 mph (55 km/h); on that basis, it is estimated a tropical depression developed eight hours earlier and into a tropical storm by the time of the report. The storm tracked generally to the north-northwest,[4] passing about 300 mi (480 km) northeast of Saint Martin. Based on continuity and subsequent reports, it is estimated the storm intensified into a hurricane on September 10. Early on September 12, a ship reported a barometric pressure of 947 mbar (28.0 inHg) in the periphery of the storm while reporting winds of 70 mph (110 km/h). This suggested winds of 140 mph (220 km/h), making it the equivalent of a modern Category 4 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson scale.[4]

For over two days, the hurricane remained near peak intensity while tracking to the northwest, and during that time several ships reported low pressure and strong winds. The hurricane weakened as it turned to the north-northwest toward the eastern United States. At around 1100 UTC on September 16, the eye of the hurricane passed over Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, around which time a pressure of 957 mbar (28.3 inHg) was recorded. The eye also passed over Diamond Shoals, where a pressure of 952 mbar (28.1 inHg) was recorded. Based on the reading, it was estimated the hurricane remained about 15 mi (25 km) east of the Outer Banks, with winds of about 100 mph (160 km/h) occurring along the coast. By that time, the size of the storm had greatly increased, and hurricane force winds also extended into southeastern Virginia.[4] The hurricane turned to the northeast, ahead of an approaching cold front,[5] producing tropical storm force winds along the eastern United States through New England. After passing southeast of Cape Cod, the storm increasingly lost its tropical characteristics, and was an extratropical cyclone by 1100 UTC on September 18 when it made landfall on eastern Nova Scotia. Continuing to the northeast, the former hurricane crossed the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and subsequently near Newfoundland and Labrador, eventually dissipating on September 22 between southern Greenland and Iceland.[4]

Preparations and impact

While the hurricane was approaching the Carolinas, the Weather Bureau issued storm warnings from Jacksonville, Florida to Beaufort, North Carolina at 2100 UTC on September 14. Six hours later, these were extended northward to Virginia Capes. By 1530 UTC on September 15, forecasters predicted that the hurricane would hit North Carolina in 12 hours and ordered hurricane warnings from Wilmington, North Carolina to Cape Hatteras. At the same time, the storm warning was expanded northward to Boston, Massachusetts, and later to Eastport, Maine. The early warnings gave ample time for preparation for the storm in Norfolk, reducing damages considerably.[3] Residents in Virginia evacuated farther inland to escape the storm.[6]

The outer rainbands of the hurricane dropped moderate to heavy rainfall, peaking at 12.6 in (320 mm) in Cape Hatteras.[5] Due to the storm remaining offshore, damage was much less than another hurricane less than a month prior. Damage from this hurricane was heaviest near New Bern, North Carolina, where the storm surge reached 3 to 4 ft (0.91 to 1.22 m), which was 2 ft (0.61 m) higher than the record set in 1913.[3] Much of the town was flooded due to the high tide and swollen nearby rivers.[6] Strong winds in the city uprooted several trees and damaged roofs. Morehead City suffered similar but slightly lesser damage, including hundreds of downed trees, and Beaufort experienced one of its worst storms in the memory of its residents.[3] Across the region, the storm downed telephone and telegraph lines. Several roads were washed out, and there was moderate agriculture damage, including hundreds of drowned livestock and flooded cotton crop. There were 21 deaths, mostly related to drownings, and damage was estimated at $4.5 million. About 1,000 people were left homeless.[7] After the storm, relief agencies provided food and medical crews for the storm victims.[8]

In southeastern Virginia, winds reached 79 mph (128 km/h).[4] At Sewell's Point in Norfolk, the storm produced 8.3 ft (2.5 m) high tides, which turned the peninsula containing New Point Comfort Light into an island.[9] Several roads were flooded, which disrupted traffic and forced residents to travel by rowboat.[7] About 2,000 people lost power, and due to well-executed preparations, there were two deaths in the state.[10] Damage was estimated at $250,000.[7] Outside of Virginia, damage was minimal north of Cape Henry. Wind peaks included 48 mph (77 km/h) in Atlantic City, New Jersey and 52 mph (84 km/h) on Block Island.[3] A boat required rescue in the Delaware Bay.[6] Precipitation fell on the western periphery of the hurricane, associated with an approaching cold front. In Provincetown, Massachusetts, the storm dropped 12.3 in (310 mm) of rainfall it passed the region.[5] In New England, high waves damaged waterfront properties. On Block Island, two boats were damaged, and another sank.[7] In Maine, the rainfall flooded cellars and damaged roads. Two people were reported missing in Boothbay Harbor after venturing into the storm in a small boat.[11]

Still maintaining strong winds by the time it struck Canada, the former hurricane washed one boat ashore, left three missing, and capsized one. One person was presumed killed when his boat sunk in Lockeport, Nova Scotia. The storm dropped heavy rainfall across the region, including 1.1 in (27 mm) in Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, and about 3 in (75 mm) in 15 hours in Gagetown, New Brunswick; there, the rains flooded roads and damaged crops. At Harvey Station in the same province, high rainfall washed out a 75 ft (22 m) portion of a rail line.[12]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind scale was developed in 1971,[1] and has been retroactively applied to the entirety of the Atlantic hurricane database.[2]

- ↑ All damage totals are in 1933 United States dollars.

References

- ↑ Jack Williams (2005-05-17). "Hurricane scale invented to communicate storm danger". USA Today. Retrieved 2013-08-04.

- ↑ Chronological List of All Continental United States Hurricanes: 1851-2012 (Report). Hurricane Research Division. June 2013. Retrieved 2013-08-03.

- 1 2 3 4 5 C. L. Mitchell (October 1933). "Tropical Disturbances of September 1933" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review (American Meteorological Society) 61 (9): 275–276. Bibcode:1933MWRv...61..274M. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1933)61<274:TDOS>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 2013-09-17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Chris Landsea; et al. (May 2012). Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT (1933) (Report). Hurricane Research Division. Retrieved 2013-09-17.

- 1 2 3 R.W. Schoner, R.W.; S. Molansky; Sinclair Weeks; F.W. Reichelderfer; W.M. Brucker; S.D. Sturgis (July 1956). Rainfall Associated With Hurricanes (And Other Tropical Disturbances) (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: National Hurricane Research Project. pp. 189, 282. Retrieved 2013-09-20.

- 1 2 3 "Storm Sweeps East Coast of Nation; Cities Raked by Gale". The Southeast Missourian. Associated Press. 1933-09-16. Retrieved 2013-09-19.

- 1 2 3 4 Mary O. Souder (September 1933). "Severe Local Storms" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review 61 (9): 291. Bibcode:1933MWRv...61..291.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1933)61<291:slss>2.0.co;2. Retrieved 2013-09-19.

- ↑ "Carolina Hit Hard on Coast". The Evening Independent. Associated Press. 1933-09-18. Retrieved 2013-09-19.

- ↑ David Roth (2007-03-01). Early Twentieth Century Virginia Hurricane History (Report). Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved 2013-09-19.

- ↑ Hurricane History (Report). Virginia Department of Emergency Management. 2012. Retrieved 2013-09-19.

- ↑ Wayne Cotterly (2002-10-17). Hurricane-No Name (1933) (PDF) (Report). Retrieved 2013-09-19.

- ↑ Detailed Storm Impacts - 1933-13 (Report). Environment Canada. 2009-11-18. Retrieved 2013-09-17.

| |||||||||||||