Execution of the Romanov family

The Russian Imperial Romanov family (Tsar Nicholas II, his wife Tsarina Alexandra and their five children Olga, Tatiana, Maria, Anastasia, and Alexei) and all those who chose to accompany them into exile – notably Eugene Botkin, Anna Demidova, Alexei Trupp and Ivan Kharitonov – were shot in Yekaterinburg on 17 July 1918.[1] The Tsar and his family were executed by Bolsheviks led by Yakov Yurovsky under the orders of the Ural Regional Soviet.

Some historians attribute the order to the government in Moscow, specifically Yakov Sverdlov and Vladimir Lenin, who wished to prevent the rescue of the Imperial Family by the approaching Czechoslovak Legion (fighting with the White Army against Bolsheviks) during the ongoing Russian Civil War.[2][3] This is supported by a passage in Leon Trotsky's diary.[4] However, a recent investigation led by Vladimir Solovyov concluded that there is no document that indicates that either Lenin or Sverdlov were responsible.[5][6][7][8]

Background

On 22 March 1917, Nicholas, no longer a monarch and addressed with contempt by the sentries as "Nicholas Romanov", was reunited with his family at the Alexander Palace in Tsarskoe Selo. He was placed under house arrest with his family by the Provisional Government, surrounded by guards and confined to their quarters.[9]

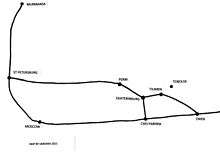

In August 1917, Alexander Kerensky's provisional government evacuated the Romanovs to Tobolsk, allegedly to protect them from the rising tide of revolution. There they lived in the former governor's mansion in considerable comfort. After the Bolsheviks came to power in October 1917, the conditions of their imprisonment grew stricter, and talk of putting Nicholas on trial grew more frequent. Nicholas was forbidden to wear epaulettes, and the sentries scrawled lewd drawings on the fence to offend his daughters. On 1 March 1918, the family was placed on soldier's rations, which meant parting with 10 devoted servants and giving up butter and coffee.[10]

As the Bolsheviks gathered strength, the government in April moved Nicholas, Alexandra, and their daughter Maria to Yekaterinburg under the direction of Vasily Yakovlev. Alexei was too ill to accompany his parents and remained with his sisters Olga, Tatiana, and Anastasia, not leaving Tobolsk until May 1918. The family was imprisoned with a few remaining retainers in Yekaterinburg's Ipatiev House, which was designated The House of Special Purpose (Russian: Дом Особого Назначения).

The Romanovs were being held by the Red Army in Yekaterinburg, since Bolsheviks initially wanted to put them on trial. As the civil war continued and the White Army (a loose alliance of anti-Communist forces) was threatening to capture the city, the fear was that the Romanovs would fall into White hands. This was unacceptable to the Bolsheviks for two reasons: first, the tsar or any of his family members could provide a beacon to rally support to the White cause; second, the tsar, or any of his family members if the tsar were dead, would be considered the legitimate ruler of Russia by the other European nations. This would have meant the ability to negotiate for greater foreign intervention on behalf of the Whites. Soon after the family was executed, the city fell to the White Army.

In mid-July 1918, forces of the Czechoslovak Legion were closing on Yekaterinburg, to protect the Trans-Siberian Railway, of which they had control. According to historian David Bullock, the Bolsheviks falsely believed that the Czechoslovaks were on a mission to rescue the family, panicked and executed their wards. The Legions arrived less than a week later and on July 25 captured the city.[11]

Execution

Around midnight, Yakov Yurovsky, the commandant of The House of Special Purpose, ordered the Romanovs' physician, Dr. Eugene Botkin, to awaken the sleeping family and ask them to put on their clothes, under the pretext that the family would be moved to a safe location due to impending chaos in Yekaterinburg.[12] The Romanovs were then ordered into a 6 m × 5 m (20 ft × 16 ft) semi-basement room. Nicholas asked if Yurovsky could bring two chairs, on which Tsarevich Alexei and Alexandra sat.[13]

The prisoners were told to wait in the cellar room while the truck that would transport them was being brought to the House. A few minutes later, an execution squad of secret police was brought in and Yurovsky read aloud the order given him by the Ural Executive Committee:

| “ | Nikolai Alexandrovich, in view of the fact that your relatives are continuing their attack on Soviet Russia, the Ural Executive Committee has decided to execute you.[14] | ” |

Nicholas, facing his family, turned and said "What? What?"[15] Yurovsky quickly repeated the order and the weapons were raised. The Empress and Grand Duchess Olga, according to a guard's reminiscence, had tried to cross themselves, but failed amid the shooting. Yurovsky reportedly raised his gun at Nicholas's torso and fired; Nicholas fell dead. Yurovsky then shot Alexei. The other executioners then began shooting chaotically until all the intended victims had fallen. Several more shots were fired and the doors opened to scatter the smoke.[15] There were some survivors, so Peter Ermakov stabbed them with bayonets because the shots could be heard outside.[15] The last to die were Tatiana, Anastasia, and Maria, who were carrying a few pounds (over 1.3 kilograms) of diamonds sewn into their clothing, which had given them a degree of protection from the firing.[16] However, they were speared with bayonets as well. Olga sustained a gunshot wound to the head. Maria and Anastasia were said to have crouched up against a wall covering their heads in terror until they were shot down. Yurovsky himself killed Tatiana and Alexei. Tatiana died from a single bullet through the back of her head.[17] Alexei received two bullets to the head, right behind the ear after the executioners realized he had not been killed by the first shot.[18] Anna Demidova, Alexandra's maid, survived the initial onslaught but was quickly stabbed to death against the back wall while trying to defend herself with a small pillow which she had carried that was filled with precious gems and jewels.[19]

An official announcement appeared in the national press, two days later. It reported that the monarch had been executed on the order of Uralispolkom under pressure posed by the approach of the Czechoslovaks.[20] Although official Soviet accounts place the responsibility for the decision with the Uralispolkom, Leon Trotsky in his diary reportedly suggested Vladimir Lenin. Trotsky wrote:

My next visit to Moscow took place after the fall of Yekaterinburg. Talking to Sverdlov I asked in passing, "Oh yes and where is the Tsar?" "It's all over," he answered. "He has been shot." "And where is his family?" "And the family with him." "All of them?" I asked, apparently with a touch of surprise. "All of them," replied Yakov Sverdlov. "What about it?" He was waiting to see my reaction. I made no reply. "And who made the decision?" I asked. "We decided it here. Ilyich [Lenin] believed that we shouldn't leave the Whites a live banner to rally around, especially under the present difficult circumstances."[4]

However, as of 2011 there has been no conclusive evidence that either Lenin or Sverdlov gave the order.[5] V.N. Solovyov, the leader of the Investigative Committee of Russia's 1993 investigation on the shooting of the Romanov family,[6] has concluded that there is no reliable document that indicates that either Lenin or Sverdlov were responsible.[7][8] He declared:

According to the presumption of innocence, no one can be held criminally liable without guilt being proven. In the criminal case, an unprecedented search for archival sources taking all available materials into account was conducted by authoritative experts, such as Sergey Mironenko, the director of the largest archive in the country, the State Archive of the Russian Federation. The study involved the main experts on the subject - historians and archivists. And I can confidently say that today there is no reliable document that would prove the initiative of Lenin and Sverdlov.— V.N. Solovyov[7]

In 1993, the report of Yakov Yurovsky from 1922 was published. According to the report, units of the Czechoslovak Legion were approaching Yekaterinburg. On 17 July 1918, Yakov and other Bolshevik jailers, fearing that the Legion would free Nicholas after conquering the town, executed him and his family. The next day, Yakov departed for Moscow with a report to Sverdlov. As soon as the Czechoslovaks seized Ekaterinburg, his apartment was pillaged.[21]

Executioners

Ivan Plotnikov, history professor at the Maksim Gorky Ural State University, has established that the executioners were: Yakov Yurovsky, G. P. Nikulin, M. A. Medvedev (Kudrin), Peter Ermakov, S. P. Vaganov, A. G. Kabanov, P. S. Medvedev, V. N. Netrebin, and Y. M. Tselms. Filipp Goloshchekin, a close associate of Yakov Sverdlov, being a military commissar of the Uralispolom in Yekaterinburg, however did not actually participate, and two or three guards refused to take part.[22]

Aftermath

Early next morning, when rumours spread in Yekaterinburg about the disposal site, Yurovsky removed the bodies and hid them elsewhere (56°56′32″N 60°28′24″E / 56.942222°N 60.473333°E). When the vehicle carrying the bodies broke down on the way to the next chosen site, Yurovsky made new arrangements, and buried most of the acid-covered bodies in a pit sealed and concealed with rubble, covered over with railroad ties and then earth (56°54′41″N 60°29′44″E / 56.9113628°N 60.4954326°E) on Koptyaki Road, a cart track (subsequently abandoned) 12 miles (19 km) north of Yekaterinburg.

In May 1979, the remains of most of the family and their retainers were found by amateur enthusiasts, who kept the discovery secret until the collapse of Communism.[23] In July 1991, the bodies of five family members (the Tsar, Tsarina, and three of their daughters) were exhumed.[24] After DNA identification, the bodies were laid to rest with state honors in the St. Catherine Chapel of the Peter and Paul Cathedral in Saint Petersburg, where most other Russian monarchs since Peter the Great lie.[25] President Boris Yeltsin and his wife attended the funeral along with Romanov relations, including Prince Michael of Kent. The remaining two bodies were discovered in 2007.[26]

On 15 August 2000, the Russian Orthodox Church announced the canonization of the family for their "humbleness, patience and meekness".[27] However, reflecting the intense debate preceding the issue, the bishops did not proclaim the Romanovs as martyrs, but passion bearers instead (see Romanov sainthood).[27] On 1 October 2008, the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation ruled that Nicholas II and his family were victims of political repression and rehabilitated them.[28][29]

On Thursday, 26 August 2010, a Russian court ordered prosecutors to reopen an investigation into the murder of Tsar Nicholas II and his family, although the Bolsheviks believed to have shot them in 1918 had died long before. The Russian Prosecutor General's main investigative unit said it had formally closed a criminal investigation into the killing of Nicholas because too much time had elapsed since the crime and because those responsible had died. However, Moscow’s Basmanny Court ordered the re-opening of the case, saying that a Supreme Court ruling blaming the state for the killings made the deaths of the actual gunmen irrelevant, according to a lawyer for the Tsar’s relatives and local news agencies.[30]

Over the years, a number of people have claimed to be survivors of the ill-fated family. The process to identify the remains was exhaustive. Russian authorities sent samples to Britain and to the United States for DNA analysis. The tests concluded that five of the skeletons were members of one family and four were unrelated. Three of the five were determined to be the children of two parents:

- The mother was linked to a maternal line relation, Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, grandson of Alexandra's oldest sister Victoria, Marchioness of Milford-Haven, who gave a DNA sample that matched that of the remains.

- The father was determined to be related to Grand Duke George Alexandrovich, younger brother of Nicholas II.

British scientists said they were more than 98.5% sure that the remains were those of the Tsar, his family and their attendants.[31][32] Relics from the Ōtsu Scandal, a failed 1891 assassination-attempt on Nicholas, failed to provide sufficient evidence due to contamination. Nicholas's skeleton was confirmed to be his after it was excavated on 22 June 1992. On 5 December 2008 Russian and American scientists using DNA analysis definitively identified the remains excavated in 1991 as those of Nicholas II.[33]

See also

References

- ↑ Robert K. Massie (2012). The Romanovs: The Final Chapter. Random House. pp. 3–24.

- ↑ Robert Gellately. Lenin, Stalin, and Hitler: The Age of Social Catastrophe Knopf, 2007 ISBN 1-4000-4005-1 p. 65.

- ↑ Figes, Orlando (1997). A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1891–1924. Penguin Books. p. 638. ISBN 0-19-822862-7.

- 1 2 King, G. (1999). The Last Empress, Replica Books, p. 358. ISBN 0735101043.

- 1 2 The Daily Telegraph (17 January 2011). "No proof Lenin ordered last Tsar's murder".

- 1 2 "Расследование убийства Николая II и его семьи, продолжавшееся 18 лет, объявлено завершенным" (in Russian). НТВ-новости. Archived from the original on 2013-02-11. Retrieved 2012-12-29.

- 1 2 3 ""Уголовное дело цесаревича Алексея". На вопросы обозревателя "Известий" Татьяны Батенёвой ответил следователь по особо важным делам Следственного комитета Российской Федерации Владимир Соловьёв". 17 January 2011.

- 1 2 Интервью следователя Соловьёв, Владимир Николаевич (следователь) - В. Н. Соловьёва и Аннинский, Лев Александрович - Л. А. Аннинского (2008). Расстрельный дом (in Russian).

- ↑ Tames, p. 56

- ↑ Tames, p. 62

- ↑ Bullock, David (2012) The Czech Legion 1914–20, Osprey Publishing ISBN 1780964587

- ↑ Massie (2012). The Romanovs: The Final Chapter. pp. 3–24.

- ↑ Massie (2012). The Romanovs: The Final Chapter. p. 4.

- ↑ William Clarke (2003). The Lost Fortune of the Tsars. St. Martin's Press. p. 66.

- 1 2 3 100 великих казней, M., Вече, 1999, p. 439 ISBN 5-7838-0424-X

- ↑ Massie, p. 8

- ↑ King G. and Wilson P., The Fate of the Romonovs, p. 303

- ↑ Massie, p. 6

- ↑ Radzinsky (1992), pp. 380–393

- ↑ Steinberg, Mark D.; Khrustalëv, Vladimir M. and Tucker, Elizabeth (1995). The Fall of the Romanovs. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07067-5.

- ↑ "Murder of the Imperial Family - Yurovsky Note 1922 English". Alexander Palace. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ↑ Plotnikov, Ivan (2003). О команде убийц царской семьи и ее национальном составе Журнальный зал, No. 9 (Russian)

- ↑ Massie, pp. 32–35

- ↑ Massie, pp. 40 ff.

- ↑ "Romanovs laid to rest". BBC News. 17 July 1998.

- ↑ Harding, Luke (25 August 2007). "Bones found by Russian builder finally solve riddle of the missing Romanovs". The Guardian (London). Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- 1 2 "Nicholas II And Family Canonized For 'Passion'". New York Times. 15 August 2000. Retrieved 10 December 2008.

- ↑ BBCNews (1 October 2008). Russia's last tsar rehabilitated. Retrieved on 1 October 2008

- ↑ Blomfield, Adrian (1 October 2008). Russia exonerates Tsar Nicholas II The Telegraph.

- ↑ The New York Times, 27 August 2010

- ↑ Gill, P; Ivanov, PL; Kimpton, C; Piercy, R; Benson, N; Tully, G; Evett, I; Hagelberg, E; Sullivan, K (1994). "Identification of the remains of the Romanov family by DNA analysis". Nature Genetics 6 (2): 130–5. doi:10.1038/ng0294-130. PMID 8162066.

- ↑ Van der Kiste, John and Hall, Coryne (2004) Once A Grand Duchess: Xenia, Sister of Nicholas II, Sutton Publishing p. 174 ISBN 0750935219

- ↑ Coble, Michael D.; et al. (2009). "Mystery solved: the identification of the two missing Romanov children using DNA analysis". PLOS ONE 4 (3): e4838. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004838. PMC 2652717. PMID 19277206.

Further reading

- Helen Rappaport. The Last Days of the Romanovs: Tragedy at Ekaterinburg. St. Martin's Griffin, 2010. ISBN 978-0312603472

- Robert K. Massie (2012). The Romanovs: The Final Chapter. Random House. pp. 3–24.

- Shay McNeal. The Secret Plot to Save the Tsar: New Truths Behind the Romanov Mystery. HarperCollins, 2003. ISBN 0-06-051755-7, ISBN 978-0-06-051755-7

- Radzinsky, Edvard. The last Tsar: the life and death of Nicholas II (Random House, 2011)

- Slater, Wendy. The many deaths of tsar Nicholas II: relics, remains and the Romanovs (Routledge, 2007)

- Tames, R (1972) Last of the Tsars, Pan Books, ISBN 0330029029

- Candace Fleming "The Family Romanov, Murder, Rebellion & the fall of Imperial Russia"

External links

- An eyewitness account (Eyewitnesstohistory.com)

- In search of the Romanovs (Time.com)

- Execution Of The Romanov Family on YouTube as seen in the movie The Romanovs: An Imperial Family

- Alexander Palace Time Machine

- In Memory of the Royal Martyrs 17 July 1918

| ||||||||||||||||