149th Armor Regiment

| 149th Armor Regiment | |

|---|---|

|

Coat of arms | |

| Active | 1959–2007 |

| Country |

|

| Branch |

|

| Type | Armor |

| Size | Regiment |

| Garrison/HQ |

Salinas, CA (1959–96) Presidio of Monterey, CA (1996–99) Seaside, CA (1999–2007) |

| Motto | Men and Steel[1] |

| Vehicles | M60A3 |

| Engagements |

Border War |

| Decorations |

Presidential Unit Citation (3) Philippine Presidential Unit Citation[2][3] |

| Insignia | |

| Distinctive unit insignia |

|

The 149th Armor Regiment was an armor regiment that was part of the California Army National Guard. Its lineage dates back to a cavalry unit organized in 1895;[4] it was deactivated as regiment the 2007 as the 149th Armored Regiment.[5] The unit, in all its incarnations, was activated for multiple natural disasters, border service,[4] peacekeeping,[6] two domestic riots,[4][7] and two foreign wars.[4] The regiment is recognized by the United States Army as a valid regiment in the United States Army Regimental System, albeit inactive.[8]

History

Cavalry and World War I

Initially organized as Troop C of cavalry at Salinas on 5 August 1895, being the first national guard unit formed in the Central Coast region.[4] The troop's first activation was when it was called up to provide law and order in San Francisco following the earthquake in 1906, using Golden Gate Park as its base of operations.[4] In 1911 the troop was, was redesignated as being part of 1st Squadron of Cavalry.[3] In 1916, the unit was activated for federal service on the Mexican border near Nogales, Arizona;[4] it was deactivated that same year.[9] Drafted into federal service in August 1917 at Camp Kearney in San Diego,[4] it was redesignated as Company B of the 145th Machine Gun Battalion, as an element of the 40th Division; in May 1919 it was demobilized at the Presidio of San Francisco.[3][4]

194th Tank Battalion

The unit's heritage as an armor unit dates back to 1924 when it was reorganized as the 40th Tank Company for the 40th Division being equipped with eight French Renault light tanks.[10] Its first activation was due to a strike by Longshoreman in 1934 for eight days.[10] In 1937 the company received the M2A2.[10]

In 1940, the company was designated as Company C, 194th Tank Battalion; other tank companies in Brainerd, Minnesota (Company A) and Saint Joseph, Missouri (Company B) formed the rest of the battalion.[11] A large part of Company C were Salinas High School graduates from the classes of 1938 and 1939.[12] The battalion was mustered into federal service on 10 February 1941, and began training at Fort Lewis, in Washington;[10] their, on 22 February, the battalion finally assembled as an entire battalion.[13] Rated among the best tank battalions in the Army, the battalion was equipped with 54 new M3 Stuart light tanks.[10]

Deployment

Company B was detached from the battalion, being sent to Alaska;[13] the rest of the battalion boarded the SS President Coolidge in San Francisco on 8 September, bound for Manila.[4] Also aboard the Coolidge was the 200th Coast Artillery Regiment from New Mexico, and the Air Corps' 27th Bombardment Group.[14] The unit thus had the privilege of becoming the first U.S. armored units to serve overseas.[10]

On 26 September 1941 the 194th, along with the 17th Ordnance Company, arrived in Manila, and was then assigned to Fort Stotsenburg.[15] There the unit found supplies to be unavailable, especially gasoline and spare parts; worse, ammunition for the tank's 37-mm main gun was never shipped to the Philippines causing the tankers to improvise ammunition in the following campaign.[10] The 192d arrived in the Philippines on 20 November; joining with the 194th and the 17th, they formed the 1st Provision Tank Group, under the command of Brigadier General Weaver.[13][16][17][18]

World War II

Clark Field and withdrawal

The beginning of World War II found Company C in defensive positions around Clark Field, where on 8 December the first Japanese attacks occurred leading to the destruction of half of the Far East Air Force; of the nine Japanese fighters shot down that day, Private Earl G. Smith of Company C was credited with downing one of them.[4][10] Due to this action, the unit became the first California National Guard unit to see combat.[19] Detached from the rest of the battalion on 12 December 1941, it was attached to the South Luzon Force.[10] On 13 December, Company C moved to Tagaytay Ridge, attempting to apprehend fifth columnists who had been launching flares near ammo dumps at night; this would continue until Christmas Eve.[4][13] On 23 December 1941, General MacArthur initially having confidence in being able to defend the entire archipelago under war plan Rainbow Five, and with the advances of Japanese forces after landing at Lingayen Gulf dashing his confidence, he ordered a reversion to War Plan Orange and ordered USAFFE forces to withdraw to the Bataan Peninsula.[20]:151–72

Assigned to the area east of Mount Banahao and attached to the Philippine Army's 1st Infantry Regiment of the 1st Infantry Division.[21]:191 The commanding general of South Luzon Force, Brigadier General Jones,[22] upon hearing that the 1st Infantry Regiment premature movement westward away from their position at Sampaloc by a motorcycle messenger of the Company C on Christmas, he immediately made contact with the unit, and instructed them to engage the Japanese who had landed at Mauban.[21]:193 Deciding to go ahead and conduct reconnaissance, using a halftrack from Company C, he and the halftrack crew were engaged by a Japanese patrol north of the town of Piis. During the engagement the halftrack became immobilized in a ditch, however the crew was able to disperse the patrol allowing BG Jones and the crew to carry the halftrack's machine guns back to friendly lines.[10][21] For their action BG Jones recommended the crew receive the Distinguished Service Cross; however by the time action was taken on the recommendation (April 1946), the awarding was reduced to a Silver Star and only one of the five crewmembers (Sergeant Leon Elliot) was still alive.[10]

The next day the 2nd platoon of the company was ordered by a Filipino Major Rumbold to attack the Japanese, who were in Piis, down a narrow mountain trail. The platoon leader, Lieutenant Needham, suggested that a reconnaissance be done before the attack but was told it was unnecessary.[10][21]:194 Advancing as a column down the road, the platoon was impeded by a roadblock consisting of antitank guns, artillery, and several machine guns, which had been prepared in anticipation of exactly the type of American action that was taking place due to the firefight the night before.[21]:194 The lead tank, commanded by Lieutenant Needham, was hit first.[10] The second tank, commanded by Staff Sergeant Emil Morello, drove around Needham's disabled tank and ran over a roadblock and an antitank gun behind it, firing upon other Japanese positions before his tank was disabled itself; in the end five tanks, an entire platoon, were immobilized and lost and five tankers were killed.[10][23] The Japanese settled in around the tanks that night, believing all the Americans to be dead; as the front moved past them, with the Japanese advancing away from them, this allowed Morello to gather the wounded.[10] With the wounded, he escaped with the help of Filipino guides, to Manila, where he left one wounded tanker in a Catholic Hospital; with the remainder of the wounded they were able to reach Corregidor by the end of the month.[10] For this Morello was awarded the Silver Star (in 1983);[24][25][26] he later rejoined the company in Bataan.[10] This action also led the War Department to change from rivets to welding in new tank production.[10]

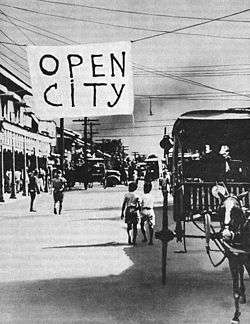

Another platoon of Company C, was attached to the Philippine Army's 51st Infantry Division, and became part of a covering force covering the division's withdrawal.[21]:196 As part of this covering force the platoon staged defensive lines near Sariaya, then Tiaong where it rejoined the rest of the South Luzon Force, minus the Philippine Army's 1st Infantry Division which would rejoin the rest of the South Luzon Force at Santiago.[21]:197 From there the force bypassed Manila, which had been declared an open city,[27] withdrawing northward to join the rest of the American-Filipino forces heading to Bataan.[21]:200 However, due to unfamiliarity with the geography, Company C passed through the city, with one of the tanks becoming immobile after hitting the Rizal Monument in the darkness; the tank crew of the immobilized tank eventually departed the city on Bren Gun Carriers driving by Filipino soldiers.[10]

At Calumpit there was an important bridges over the Pampanga River, which connected Bataan to the forces that were now north of Manila.[28]:203 To defend these bridges the 194th took up positions at Apalit, covering the west bank of the river and ensuring the path to the units defending the bridges; To the south Compancy C of the 194th covered the southern front at Bocaue.[28]:201 While there observing empty trucks departing Manila to Bataan, the battalion organized the shipment of 12,000 gallons of aviation gasoline and 6 truckloads of canned food from Manila;[29] this was little consultation as the lack of those supplies, that were either destroyed or left behind, led to immediate rationing which reduced the fighting ability of those on Bataan later on.[10][30][31] With the bridges having been successfully defended by other units (including the 192nd),[16][32] Company C became the last unit to cross the bridges before they were demolished to slow down the Japanese advance.[10]

Moving northward on the first days of 1942, the 194th took up position east of San Fernando, with the rest of the Provisional Tank Group covering the withdrawal of the remaining American-Filipino forces into Bataan south of town on the banks of the Pampanga River.[33] While in defensive positions, the first tank-on-tank combat occurred for that 194th, when five Japanese Type 89As approached; the Japanese unit, having not conducted reconnaissance prior to their movement, was caught by the 194th in an open field. All the Japanese tanks were destroyed.[34] With the rest of the forces passing through the town, the tankers detonated the bridge over the San Fernando and withdrew to Guagua.[33]

Ten days since the American-Filipino forces began withdrawing, they found themselves conducting their final delaying actions, while the rest of the force prepared the defenses in Bataan,[35] giving those forces three additional days.[10] The first of those for Company C were due to it serving as an advance force of the main line, north of Guagua, there the held for three and a half hours.[35]:221 Guagua was not held for long, less than two days, and Company C covered the retreat of the remainder of the battalion.[35]:222 While Company C was covering the flank of the forces retreating south from Guagua, a large enemy force of 500 to 800 Japanese soldiers approached behind three Philippine Constabulary officers waving a white flag; the covering force, consisting of two tanks and two half-tracks, opened fire upon the enemy killing them in the open.[34][35]:223

Bataan

Surrender and occupation

Some of the soldiers chose not to comply with orders and surrender, instead becoming guerrillas, resisting the Japanese occupation;[36] one was PFC Eugene Zingheim, a radio operator, who would later be executed after being caught by the Japanese due to malaria in 1943.[37][38]

Post World War II

After World War II, the 194th Tank Battalion was inactivated in April 1946, then redesignated as the 199th Tank Battalion in June of that same year.[3] In 1949, the unit was reorganized and redesignated as the 149th Heavy Tank Battalion, as an element of the 49th Infantry Division, and then elevated to a parent regiment within the Combat Arms Regimental System in 1959.[3] Due to the Watts Riots, while the unit was having weekend drill, the unit was called up to man roadblocks; while there the tankers were fired upon.[39] In 1968, the 1st Battalion of the regiment was detached from the 49th and became an element of the 40th Infantry Division in 1974.[3]

In 1982, 3rd Battalion conducted winter training at Fort Ripley.[40] In 1989, the regiment was withdrawn from CARS and reorganized in the United States Army Regimental System.[3] The regiment was activated in May 1992 for Operation Garden Plot due to the 1992 Los Angeles riots.[7][41] In 1994, the regiment was part of the 3rd brigade of the 40th Infantry Division.[42] In 1996 the regiment's headquarters moved to the Presidio of Monterey.[5] Due to the force reduction in other units in 1997, the regiment saw an increase in its size.[43] In 1999 the regiment's headquarters was moved once again to Seaside.[5] Activated for Operation Noble Eagle III in 2003,[44][45] 1st Battalion was activated to conduct NATO peacekeeping duties as part of the Kosovo Force.[6] Following redesignated of the regiment from armor to armored in 2005, it was redesignated as the 340th Brigade Support Battalion in 2007, a part of the 65th Fires Brigade (United States).[5][46][47] Prior to the regiment being disbanded, and redesignated, almost 90% of the soldiers of the regiment had already seen combat in the War on Terror.[39]

Awards

- DEFENSE OF THE PHILIPPINES

- LUZON 1941–1942

- BATAAN PENINSULA[2]

![]() Philippine Presidential Unit Citation[2]

Philippine Presidential Unit Citation[2]

- 7 December 1941 to 10 May 1942[3]

Campaign streamers:

World War I streamer without inscription

Philippine Islands

Aleutian Islands (Company C, 1st Battalion)[2]

Lineage

- Organized 5 August 1895 in the California National Guard at Salinas as Troop C, Cavalry.

- Redesignated 1 May 1911 as Troop C, 1st Squadron of Cavalry.

- Mustered into Federal service 26 June 1916 at Sacramento; mustered out of Federal service 17 November 1916 at Los Angeles.

- Drafted into Federal service 5 November 1917.

- Reorganized and redesignated 3 October 1917 as Company B, 145th Machine Gun Battalion, an element of the 40th Division.

- Demobilized 20 May 1919 at the Presidio of San Francisco, California.

- Reorganized and Federally recognized 18 June 1924 in the California National Guard at Salinas as the 40th Tank Company and assigned to the 40th Division.

- Reorganized and redesignated 1 September 1940 as Company C, 194th Tank Battalion, and relieved from assignment to the 40th Division.

- Inducted into Federal service 10 February 1941 at Salinas.

- Surrendered 9 April 1942 to the Japanese 14th Army in the Philippine Islands.

- Inactivated 2 April 1946 in the Philippine Islands.

- Expanded and redesignated 21 June 1946 as the 199th Tank Battalion.

- Reorganized and Federally recognized 27 May 1947 with Headquarters at Salinas.

- Reorganized and redesignated 1 February 1949 as the 149th Heavy Tank Battalion and assigned to the 49th Infantry Division.

- Reorganized and redesignated 1 September 1950 as the 149th Tank Battalion.

- Consolidated 1 May 1959 with the 170th Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion and consolidated unit reorganized and redesignated as the 149th Armor, a parent regiment under the Combat Arms Regimental System, to consist of the 1st Medium Tank Battalion and the 2d Reconnaissance Squadron, elements of the 49th Infantry Division.

- Reorganized 1 March 1963 to consist of the 1st and 3d Battalions, elements of the 49th Infantry Division, and the 4th Medium Tank Battalion.

- Reorganized 1 April 1964 to consist of the 1st and 3d Battalions, elements of the 49th Infantry Division, and the 4th Battalion.

- Reorganized 29 January 1968 to consist of the 1st Battalion.

- Reorganized 13 January 1974 to consist of the 1st Battalion, an element of the 40th Infantry Division.

- Withdrawn 19 January 1988 from the Combat Arms Regimental System and reorganized under the United States Army Regimental System.

- 1st Battalion ordered into active Federal service 1 May 1992 at home stations; released from active Federal service 9 May 1992 and reverted to state control.

- Location of Headquarters changed 1 June 1996 to the Presidio of Monterey; on 1 October 1999 to Seaside, California.

- Ordered into active Federal service 14 August 2002 at home stations; released from active Federal service 2 September 2003 and reverted to state control.

- Redesignated 1 October 2005 as the 149th Armored Regiment.

- Consolidated 1 September 2007 with the 340th Support Battalion and consolidated unit designated as the 340th Support Battalion.[5]

Legacy

During the Bataan Death March, Salinas had the unfortunate distinction of having the highest number of soldiers per capita in the march, of any city in the United States.[48] Of the 105 soldiers who left Salinas, who made up a large part of the 114 men who were part of Company C, 46 or 47 survived the war.[48][49][50] In October 2011, Sergeant Roy Diaz was reported to be the last surviving Salinas member of Company C;[49] he was the subject of an Emmy Award winning story produced by KTEH,[51][52][53] and in February 2012, it was proposed that an access road off Airport Boulevard in Salinas, leading to Salinas Municipal Airport, be named for Diaz.[54]

Descendant units

- 115th Regional Support Group[55]

- 340th Support Battalion[5]

- 670th Military Police Company, 185th Military Police Battalion, 49th Military Police Brigade[56]

Memorials

In 2006, a memorial was erected at the Boronda History Center to commemorate the soldiers of Company C 194th Tank Battalion.[48][57] This follows a memorial located at Camp San Luis Obispo depicting the actions of SSG Morello's tank on 26 December 1941.[58]

See also

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Army Center of Military History document "340th Support Battalion".

This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Army Center of Military History document "340th Support Battalion".

- ↑ "149 Armor Regiment". The Institute of Heraldry. Office of the Administrative Assistant to the Secretary of the Army. 28 October 2011. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

"149th Armor Regiment". California State Military Museum. California State Military Department. 2010. Retrieved 23 March 2013. - 1 2 3 4 "149th Armor Regiment". California State Military Museum. California State Military Department. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Pope, Jeffrey Lynn; Kondratiuk, Leonid E., eds. (1995). Armor-Cavalry Regiments: Army National Guard Lineage. DIANE Publishing. pp. 44–45. ISBN 9780788182068. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Anderson, Burton (October 2004). "A History of the Salinas National Guard Company 1895–1995" (PDF). News. Monterey County Historical Society. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Lineage and Honors 340th Support Battalion". United States Army Center of Military History. United States Army. 20 December 2011. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- 1 2 Stahl, Zachary (21 February 2005). "Veterans fight for unit". The Salinas Californian. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- 1 2 "Brigadier General Matthew P. Beevers". General Officer Management. National Guard Bureau. August 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ↑ Johnson, Danny M. (22 February 2013). "Regimental Systems of the California National Guard". California State Military Museum. California State Military Department. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- ↑ Landis, Brett A. "On the Mexican Border, 1914 and 1916". California State Military Museum. California State Military Department. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Anderson, Burton (1996). "Company C, 194th Tank Battalion in the Philippines, 1941–42" (PDF). Armor (United States Army Armor School) CV (3): 32–36. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ↑ Van den Berg, William J. (2004). "Employing an Armor Quick Reaction Force in the Area Defense: The 194th Tank Battalion in Action During the Luzon Defensive Campaign 1941–42" (PDF). Armor (United States Army Armor School). CXVIII (2). Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ↑ "War Tests a Town: With personal stake in WWII, Salinas emerged as full-fledged city.". The Salinas Californian (Gannett). 22 May 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

The unit's ranks were filled largely from the Salinas High School classes of 1938 and `39.

- 1 2 3 4 McHenny, William S.; William D. Beard; Alfred Seunlau; David O. Fleming; Leo Nawn, Jr.; William A. Burke; Robert S. Ferrari; Francis J. Kelly; John H. Cleveland (1950). Armor on Luzon (Comparison of Employment of Armored Units in the 1941—1942 and 1945 Luzon Campaigns) (PDF) (Research Report). United States Army. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ↑ Martin, Adrian R.; Stephenson, Larry W. (2008). Operation PLUM: The Ill-fated 27th Bombardment Group and the Fight for the Western Pacific. Texas A&M University Press. p. 36. ISBN 9781603440196. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- ↑ Dooley, Colonel Thomas (1999). "The First U.S. Tank Action in World War II". In Merriam, Ray. World War II Journal. Volume 5 of World War II Journal Series. Merriam Press. p. 14. ISBN 9781576381649. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- 1 2 Fredriksen, John C. (2010). The United States Army: A Chronology, 1775 to the Present. ABC-CLIO. p. 260. ISBN 9781598843446. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- ↑ "The Provisional Tank Group: United States Army Forces in the Far East" (PDF). The Office of the Adjutant General, Kentucky National Guard. 15 June 1961. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- ↑ James, D. Clayton, editor (2012). South to Bataan, North to Mukden: The Prison Diary of Brigadier General W. E. Brougher. University of Georgia Press. p. 12. ISBN 9780820337951. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- ↑ "California and the Second World War:A Short History of the California National Guard in World World II". California Military Museum. California State Military Department. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- ↑ Morton, Louis (2000) [1960]. "The Decision To Withdraw to Bataan". In Greenfield, Kent Roberts. Command Decisions. United States Army Center of Military History. pp. 151–172. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Morton, Louis (2006) [1953]. "XI. Withdrawal in the South". In Greenfield, Kert Roberts. The Fall of the Philippines. United States Army in World War II. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ↑ Leary, William M. (2003). MacArthur and the American Century: A Reader. U of Nebraska Press. p. 97. ISBN 9780803280205. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ↑ Millsap, Don. "At a Roadblock on the Road to Bataan". Heritage Series. National Guard Bureau. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ↑ "Staff Sergeant Emil C. Morello Army". Military Times Hall of Valor. Gannett Government Media. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ↑ Major General Robert M. Joyce (13 March 1984). "General Orders No. 7" (PDF). Headquarters, Department of the Army. United States Army. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ↑ Jim Opolony (2002). "Sgt. Emil Severine Morello". Patriot Project. Whitman Elementary, Lewiston, Idaho. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ↑ Cogan, Frances B. (2000). Captured: The Japanese Internment of American Civilians in the Philippines, 1941–1945. University of Georgia Press. p. 41. ISBN 9780820321172. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- 1 2 Morton, Louis (2006) [1953]. "XII. Holding the Road to Bataan". In Greenfield, Kert Roberts. The Fall of the Philippines. United States Army in World War II. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ↑ Rovere, Richard Halworth; Schlesinger, Arthur Meier (1951). General MacArthur and President Truman: The Struggle for Control of American Foreign Policy. Transaction Publishers. p. 55. ISBN 9781560006091. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- ↑ Captain Harold A. Armold (November–December 1946). "The Lesson of Bataan: The Story of the Philippine and Bataan Quartermaster Depots". Quartermaster Museum. United States Army. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- ↑ Colonel Roy C. Hilton (29 January 1946). "G-4 of Luzon Force Report". Battle for Bataan!. New Mexico State University. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- ↑ Dooley, Colonel Thomas (1999). "The First U.S. Tank Action in World War II". In Merriam, Ray. World War II Journal. Volume 5 of World War II Journal Series. Merriam Press. p. 17. ISBN 9781576381649. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- 1 2 Morton, Louis (2006) [1953]. "XII. Holding the Road to Bataan". In Greenfield, Kert Roberts. The Fall of the Philippines. United States Army in World War II. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History. pp. 214–215. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- 1 2 Vandenberg, Major William J. (2009). "Executing the Double Retrograde Delay" (PDF). The Foxhole (196th Regimental Combat Team Association) XVI (2): 4–9. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Morton, Louis (2006) [1953]. "XIII. Into Bataan". In Greenfield, Kert Roberts. The Fall of the Philippines. United States Army in World War II. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History. p. 216. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- ↑ Albanese, Jim (22 May 2009). "The 194th lives on in our hearts". The Salinas Californian (Gannett). Retrieved 25 September 2012.

Some of the Allied troops escaped to Corregidor and a few fled into the jungle to wage an effective three-year guerrilla campaign.

- ↑ Decker, Malcolm (2008). From Bataan to Safety: The Rescue of 104 American Soldiers in the Philippines. McFarland. p. 79. ISBN 9780786433964. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ↑ "Tec 5 Eugene P. Zingheim". Bataan Commemorative Research Project. Proviso East High School, Proviso Township High Schools District 209. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- 1 2 Blumenfeld, Zoe (12 November 2006). "Local veteran reflects on his 30-year service with Santa Cruz National Guard unit". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ↑ "This was Brainerd-Jan.27". Brainerd Dispatch. 26 February 2012. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ↑ "Assistant Adjutant General". California National Guard. State of California. 2011. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ↑ "40th Infantry Division (Mechanized) Order of Battle, 1994". California Military Museum. California State Military Department. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ↑ "FY 1997 Reserve Component Reduction Plan". Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Reserve Affairs. Department of Defense. 14 January 1997. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ↑ CPT Alana Schwermer; SFC Steve Payer (Summer 2003). "Operation NOBLE EAGLE III". The Grizzly. California National Guard. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ↑ "National Guard and Reserve Units Called to Active Duty (September 10, 2003)" (PDF). Department of Defense. 10 September 2003. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- ↑ Blumenfeld, Zoe (7 November 2006). "Weaponry moved out of DeLaveaga armory, troops reassigned". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ↑ "California Center for Military History" (PDF). Military History Unit. State of California. 2006. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- 1 2 3 Bell, Katharine (22 May 2009). "Memorial honors WWII soldiers". The Salinas Californian (Gannett). Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- 1 2 Dave Nordstrand (21 October 2011). "Roy Diaz of Salinas, Bataan Death March survivor, celebrates 95th birthday". The Salinas Californian (Gannett). Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ↑ Jim Albanese (22 May 2009). "Bataan ordeal remembered". The Salinas Californian (Gannett). Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ↑ Keith Sanders (July 2011). "Emmy® 2011: This Show Was Golden!" (PDF). Off Camera. The National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences: San Francisco/Northern California Chapter. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ↑ Roy Diaz. KTEHTV. 2010. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ↑ Meredith Gandy (13 June 2011). "KQED wins seven Northern California Emmy® Awards". Pressroom. KQED (TV). Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ↑ Gary Peterson (28 February 2012). "Report to the City Council" (PDF). Street Naming Committee. City of Salinas. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ↑ Sebby, Daniel M. "115th Area Support Group". California Military Museum. California State Military Department. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ "670th Military Police Company". California Military Museum. California Military Department. 18 May 2008. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ "Bataan Memorial". Salinas. Monterey County Historical Society. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ↑ "Camp San Luis Obispo, Bataan Memorial". California Military Museum. California State Military Department. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

External links

- 340th Brigade Support Battalion

- 149th Armor Regiment Association

- Roster of California members of the 194th Tank Battalion during World War II