Eucalyptol

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

1,3,3-Trimethyl-2-oxabicyclo[2,2,2]octane | |||

| Other names

1,8-Cineole 1,8-Epoxy-p-menthane | |||

| Identifiers | |||

| 470-82-6 | |||

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL485259 | ||

| ChemSpider | 2656 | ||

| DrugBank | DB03852 | ||

| 2464 | |||

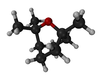

| Jmol interactive 3D | Image | ||

| KEGG | D04115 | ||

| PubChem | 2758 | ||

| UNII | RV6J6604TK | ||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C10H18O | |||

| Molar mass | 154.249 g/mol | ||

| Density | 0.9225 g/cm3 | ||

| Melting point | 1.5 °C (34.7 °F; 274.6 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 176 to 177 °C (349 to 351 °F; 449 to 450 K) | ||

| Pharmacology | |||

| ATC code | R05 | ||

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| | |||

| Infobox references | |||

Eucalyptol is a natural organic compound that is a colorless liquid. It is a cyclic ether and a monoterpenoid.

Eucalyptol is also known by a variety of synonyms: 1,8-cineol, 1,8-cineole, cajeputol, 1,8-epoxy-p-menthane, 1,8-oxido-p-menthane, eucalyptol, eucalyptole, 1,3,3-trimethyl-2-oxabicyclo[2,2,2]octane, cineol, cineole.

In 1870, F.S. Cloez identified and ascribed the name eucalyptol to the dominant portion of Eucalyptus globulus oil.[1] Eucalyptus oil, the generic collective name for oils from the Eucalyptus genus, should not be confused with the chemical compound eucalyptol.

Composition

Eucalyptol comprises up to 90 percent of the essential oil of some species of the generic product Eucalyptus oil,[1] hence the common name of the compound. It is also found in camphor laurel, bay leaves, tea tree, mugwort, sweet basil, wormwood, rosemary, common sage, cannabis sativa, and other aromatic plant foliage. Eucalyptol with a purity from 99.6 to 99.8 percent can be obtained in large quantities by fractional distillation of eucalyptus oil.

Although it can be used internally as a flavoring and medicine ingredient at very low doses, typical of many essential oils (volatile oils), eucalyptol is toxic if ingested at higher than normal doses.[2]

Properties

Eucalyptol has a fresh camphor-like smell and a spicy, cooling taste. It is insoluble in water, but miscible with ether, ethanol, and chloroform. The boiling point is 176 °C and the flash point is 49 °C. Eucalyptol forms crystalline adducts with hydrohalic acids, o-cresol, resorcinol, and phosphoric acid. Formation of these adducts are useful for purification.

Uses

Flavoring and fragrance

Because of its pleasant spicy aroma and taste, eucalyptol is used in flavorings, fragrances, and cosmetics. Cineole-based eucalyptus oil is used as a flavouring at low levels (0.002%) in various products, including baked goods, confectionery, meat products and beverages.[3] In a 1994 report released by five top cigarette companies, eucalyptol was listed as one of the 599 additives to cigarettes.[4] It is claimed that it is added to improve the flavor.

Medicinal

Eucalyptol is an ingredient in many brands of mouthwash and cough suppressant, as well as an inactive ingredient in body powder.

Insecticide and repellent

Eucalyptol is used as an insecticide and insect repellent.[5][6]

In contrast, eucalyptol is one of many compounds that are attractive to males of various species of orchid bees, which gather the chemical to synthesize pheromones; it is commonly used as bait to attract and collect these bees for study.[7] One such study with Euglossa imperialis, a non-social orchid bee species, has shown that the presence of cineole (also eucalyptol), elevates territorial behavior and specifically attracts the male bees. It was even observed that these males would periodically leave their territories to forage for chemicals such as cineole, thought to be important for attracting and mating with females, to synthesize pheromones.[8]

Toxicology

In higher-than-normal doses, eucalyptol is hazardous via ingestion, skin contact, or inhalation. It can have acute health effects on behavior, respiratory tract, and nervous system. The acute oral LD50 is 2480 mg/kg (rat). It is classified as a reproductive toxin for females and a suspect reproductive toxin for males.[2]

Scientific study

- In a 2003 study, eucalyptol was found to control airway mucus hypersecretion and asthma; after, in a previous study, the authors found eucalyptol to suppress arachidonic acid metabolism and cytokine production in human monocytes.[9][10]

- In a 2004 study, it was found to inhibit cytokine production in cultured human lymphocytes and monocytes.[11]

- In a 2004 study, eucalyptol was found to be an effective treatment for nonpurulent rhinosinusitis. Treated subjects experienced less headache on bending, frontal headache, sensitivity of pressure points of trigeminal nerve, impairment of general condition, nasal obstruction, and rhinological secretion. Side effects from treatment were minimal.[12]

- A 2000 study found eucalyptol to reduce inflammation and pain when applied topically.[13]

- In a 2002 study, it was found to kill leukaemia cells of two cultured human leukemia cell lines, but not cells of a human stomach cancer cell line in vitro.[14]

List of plants that contain the chemical

- Cannabis[15]

- Cinnamomum camphora, Camphor laurel (50%)[16]

- Eucalyptus cneorifolia

- Eucalyptus dives,

- Eucalyptus dumosa

- Eucalyptus globulus[17]

- Eucalyptus goniocalyx

- Eucalyptus horistes

- Eucalyptus kochii

- Eucalyptus leucoxylon

- Eucalyptus oleosa

- Eucalyptus polybractea

- Eucalyptus radiata

- Eucalyptus sideroxylon

- Eucalyptus smithii

- Eucalyptus staigeriana[18]

- Eucalyptus tereticornis

- Eucalyptus viridis

- Helichrysum gymnocephalum [19]

- Kaempferia galanga, Galangal, (5.7%)[20]

- Laurus nobilis, Bay Laurel, (45%)

- Melaleuca alternifolia, Tea-tree, (0–15%)

- Salvia lavandulifolia, Spanish sage (13%)[21]

- Turnera diffusa, Damiana[22]

- Umbellularia californica, Pepperwood (22.0%)[23]

- Zingiber officinale, Ginger

Compendial status

- British Pharmacopoeia [24]

- Martindale: The Extra Pharmacopoeia 31 [25]

N.B. Listed as "cineole" in some pharmacopoeia.

Sulfonation

- Sulfonation of Eucalyptol with SO3 in the presence of dioxane gives good analeptic/antiseptic agents.[26]

See also

References

- 1 2 Boland, D. J.; Brophy, J. J.; House, A. P. N. (1991). Eucalyptus Leaf Oils: Use, Chemistry, Distillation and Marketing. Melbourne: Inkata Press. p. 6. ISBN 0-909605-69-6.

- 1 2 "Material Safety Data Sheet - Cineole MSDS". ScienceLab. Retrieved 2012-09-27.

- ↑ Harborne, J. B.; Baxter, H. Chemical Dictionary of Economic Plants. ISBN 0-471-49226-4.

- ↑ "Cigarette Ingredients - Chemicals in Cigarettes". New York State Department of Health. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ↑ Klocke, J. A.; Darlington, M. V.; Balandrin, M. F. (December 1987). "8-Cineole (Eucalyptol), a Mosquito Feeding and Ovipositional Repellent from Volatile Oil of Hemizonia fitchii (Asteraceae)". Journal of Chemical Ecology 13 (12): 2131. doi:10.1007/BF01012562.

- ↑ Sfara, V.; Zerba, E. N.; Alzogaray, R. A. (May 2009). "Fumigant Insecticidal Activity and Repellent Effect of Five Essential Oils and Seven Monoterpenes on First-Instar Nymphs of Rhodnius prolixus". Journal of Medical Entomology 46 (3): 511–515. doi:10.1603/033.046.0315. PMID 19496421.

- ↑ Schiestl, F. P.; Roubik, D. W. (2004). "Odor Compound Detection in Male Euglossine Bees". Journal of Chemical Ecology 29 (1): 253–257. doi:10.1023/A:1021932131526. PMID 12647866.

- ↑ Schemske, Douglas W., and Russell Lande. "Fragrance collection and territorial display by male orchid bees." Animal Behaviour 32.3 (1984): 935-937.

- ↑ Juergens, U. R.; Dethlefsen, U.; Steinkamp, G.; Gillissen, A.; Repges, R.; Vetter, H. (March 2003). "Anti-Inflammatory Activity of 1.8-Cineol (Eucalyptol) in Bronchial Asthma: A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial" (pdf). Respiratory Medicine 97 (3): 250–256. doi:10.1053/rmed.2003.1432. PMID 12645832.

- ↑ Juergens, U. R.; Stöber, M.; Vetter, H. (1998). "Inhibition of Cytokine Production and Arachidonic Acid Metabolism by Eucalyptol (1.8-Cineole) in Human Blood Monocytes in vitro". European Journal of Medical Research 3 (11): 508–510. PMID 9810029.

- ↑ Juergens, U.; Engelen, T.; Racké, K.; Stöber, M.; Gillissen, A.; Vetter, H. (2004). "Inhibitory Activity of 1,8-Cineol (Eucalyptol) on Cytokine Production in Cultured Human Lymphocytes and Monocytes". Pulmonary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 17 (5): 281–287. doi:10.1016/j.pupt.2004.06.002. PMID 15477123.

- ↑ Kehrl, W.; Sonnemann, U.; Dethlefsen, U. (2004). "Therapy for Acute Nonpurulent Rhinosinusitis with Cineole: Results of a Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial". The Laryngoscope 114 (4): 738–742. doi:10.1097/00005537-200404000-00027. PMID 15064633.

- ↑ Santos, F. A.; Rao, V. S. (2000). "Antiinflammatory and Antinociceptive Effects of 1,8-Cineole, a Terpenoid Oxide Present in many Plant Essential Oils". Phytotherapy Research 14 (4): 240–244. doi:10.1002/1099-1573(200006)14:4<240::AID-PTR573>3.0.CO;2-X. PMID 10861965.

- ↑ Moteki, H.; Hibasami, H.; Yamada, Y.; Katsuzaki, H.; Imai, K.; Komiya, T. (2002). "Specific Induction of Apoptosis by 1,8-Cineole in two Human Leukemia Cell Lines, but not in a Human Stomach Cancer Cell Line". Oncology Reports 9 (4): 757–760. doi:10.3892/or.9.4.757. PMID 12066204.

- ↑ McPartland J. M., Russo E. B (2001). "Cannabis and cannabis extracts: greater than the sum of their parts?". Journal of Cannabis Therapeutics 1 (3-4): 103–132. doi:10.1300/J175v01n03_08. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ↑ Stubbs, B. J.; Brushett, D. (2001). "Leaf oil of Cinnamomum camphora (L.) Nees and Eberm. From Eastern Australia". Journal of Essential Oil Research 13 (1): 51–54. doi:10.1080/10412905.2001.9699604.

- ↑ Maciel, M. V.; Morais, S. M.; Bevilaqua, C. M.; Silva, R. A.; Barros, R. S.; Sousa, R. N.; Sousa, L. C.; Brito, E. S.; Souza-Neto M. A. (2010). "Chemical composition of Eucalyptus spp. essential oils and their insecticidal effects on Lutzomyia longipalpis". Veterinary Parasitology 167 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.09.053. PMID 19896276.

- ↑ Gilles, M.; Zhao, J.; An, M.; Agboola, S. (2010). "Chemical Composition and Antimicrobial Properties of Essential Oils of three Australian Eucalyptus Species". Food Chemistry 119 (2): 731–737. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.07.021.

- ↑ Möllenbeck, S.; König, T.; Schreier, P.; Schwab, W.; Rajaonarivony, J.; Ranarivelo, L. (1997). "Chemical Composition and Analyses of Enantiomers of Essential Oils from Madagascar". Flavour and Fragrance Journal 12 (2): 63. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1026(199703)12:2<63::AID-FFJ614>3.0.CO;2-Z.

- ↑ Wong, K. C.; Ong, K. S.; Lim, C. L. (2006). "Composition of the Essential Oil of Rhizomes of Kaempferia Galanga L.". Flavour and Fragrance Journal 7 (5): 263–266. doi:10.1002/ffj.2730070506.

- ↑ Perry NS, Houghton PJ, Theobald A, Jenner P, Perry EK (2000). "In-vitro inhibition of human erythrocyte acetylcholinesterase by salvia lavandulaefolia essential oil and constituent terpenes". J Pharm Pharmacol 52 (7): 895–902. doi:10.1211/0022357001774598. PMID 10933142.

- ↑ Balch, P. A. (2002). Prescription for Nutritional Healing: the A to Z Guide to Supplements. Penguin. p. 233. ISBN 978-1-58333-143-9.

- ↑ Kelsey, R. G.; McCuistion, O.; Karchesy, J. (2007). "Bark and Leaf Essential Oil of Umbellularia californica, California Bay Laurel, from Oregon". Natural Product Communications 2 (7): 779–780.

- ↑ The British Pharmacopoeia Secretariat (2009). "Index, BP 2009" (PDF). Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- ↑ Therapeutic Goods Administration. "Chemical Substances" (PDF). tga.gov.au. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 July 2009. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- ↑ U.S. Patent 3,397,212 eidem DE 1296646

Further reading

- Boland, D. J.; Brophy, J. J.; House, A. P. N. (1991). Eucalyptus Leaf Oils: Use, Chemistry, Distillation and Marketing. Melbourne: Inkata Press. ISBN 0-909605-69-6.

External links

- "Eucalyptus". Botanical.com.

- "Oleum Eucalypti, B.P. Oil of Eucalyptus". Henriette's Herbal.

- "MSDS - Safety data for eucalyptol". Oxford University Chemistry Department.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||