n-sphere

In mathematics, the n-sphere is the generalization of the ordinary sphere to spaces of arbitrary dimension. For any natural number n, an n-sphere of radius r is defined as the set of points in (n + 1)-dimensional Euclidean space which are at distance r from a central point, where the radius r may be any positive real number. Thus, the n-sphere centred at the origin is defined by:

It is an n-dimensional manifold in Euclidean (n + 1)-space.

In particular:

- a 0-sphere is the pair of points at the ends of a (one-dimensional) line segment,

- a 1-sphere is the circle, which is the one-dimensional circumference of a (two-dimensional) disk in the plane,

- a 2-sphere is the two-dimensional surface of a (three-dimensional) ball in three-dimensional space.

Spheres of dimension n > 2 are sometimes called hyperspheres, with a 3-sphere sometimes known as a glome. The n-sphere of unit radius centered at the origin is called the unit n-sphere, denoted Sn. The unit n-sphere is often referred to as the n-sphere.

An n-sphere is the surface or boundary of an (n + 1)-dimensional ball, and is an n-dimensional manifold. For n ≥ 2, the n-spheres are the simply connected n-dimensional manifolds of constant, positive curvature. The n-spheres admit several other topological descriptions: for example, they can be constructed by gluing two n-dimensional Euclidean spaces together, by identifying the boundary of an n-cube with a point, or (inductively) by forming the suspension of an (n − 1)-sphere.

Description

For any natural number n, an n-sphere of radius r is defined as the set of points in (n + 1)-dimensional Euclidean space that are at distance r from some fixed point c, where r may be any positive real number and where c may be any point in (n + 1)-dimensional space. In particular:

- a 0-sphere is a pair of points {c − r, c + r}, and is the boundary of a line segment (1-ball).

- a 1-sphere is a circle of radius r centered at c, and is the boundary of a disk (2-ball).

- a 2-sphere is an ordinary 2-dimensional sphere in 3-dimensional Euclidean space, and is the boundary of an ordinary ball (3-ball).

- a 3-sphere is a sphere in 4-dimensional Euclidean space.

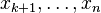

Euclidean coordinates in (n + 1)-space

The set of points in (n + 1)-space: (x1,x2,…,xn+1) that define an n-sphere, (Sn) is represented by the equation:

where c is a center point, and r is the radius.

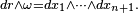

The above n-sphere exists in (n + 1)-dimensional Euclidean space and is an example of an n-manifold. The volume form ω of an n-sphere of radius r is given by

where * is the Hodge star operator; see Flanders (1989, §6.1) for a discussion and proof of this formula in the case r = 1. As a result,

n-ball

- Main article: ball (mathematics)

The space enclosed by an n-sphere is called an (n + 1)-ball. An (n + 1)-ball is closed if it includes the n-sphere, and it is open if it does not include the n-sphere.

Specifically:

- A 1-ball, a line segment, is the interior of a (0-sphere).

- A 2-ball, a disk, is the interior of a circle (1-sphere).

- A 3-ball, an ordinary ball, is the interior of a sphere (2-sphere).

- A 4-ball is the interior of a 3-sphere, etc.

Topological description

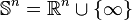

Topologically, an n-sphere can be constructed as a one-point compactification of n-dimensional Euclidean space. Briefly, the n-sphere can be described as  , which is n-dimensional Euclidean space plus a single point representing infinity in all directions.

In particular, if a single point is removed from an n-sphere, it becomes homeomorphic to

, which is n-dimensional Euclidean space plus a single point representing infinity in all directions.

In particular, if a single point is removed from an n-sphere, it becomes homeomorphic to  . This forms the basis for stereographic projection.[1]

. This forms the basis for stereographic projection.[1]

Volume and surface area

and

and  are the n-dimensional volume and surface area of the n-ball and n-sphere of radius

are the n-dimensional volume and surface area of the n-ball and n-sphere of radius  , respectively.

, respectively.

The constants  and

and  (for the unit ball and sphere) are related by the recurrences:

(for the unit ball and sphere) are related by the recurrences:

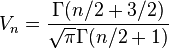

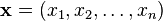

The surfaces and volumes can also be given in closed form:

where  is the gamma function. Derivations of these equations are given in this section.

is the gamma function. Derivations of these equations are given in this section.

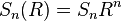

In general, the volumes of the n-ball in n-dimensional Euclidean space, and the n-sphere in (n + 1)-dimensional Euclidean, of radius R, are proportional to the nth power of the radius, R. We write  for the volume of the n-ball and

for the volume of the n-ball and  for the surface of the n-sphere, both of radius

for the surface of the n-sphere, both of radius  .

.

Interestingly, given the radius R, the volume and the surface area of the n-sphere reaches a maximum and then decrease towards zero as the dimension n increases. In particular, the volume  of the n-sphere of constant radius R in n-dimensions

reaches a maximum for dimension

of the n-sphere of constant radius R in n-dimensions

reaches a maximum for dimension  if

if  <R<

<R<  and

and  if

if  where

where  for

for  . Similarly, defining the sequence

. Similarly, defining the sequence  , the surface area

, the surface area  of the n-sphere of constant radius R in n dimensions reaches a maximum for dimension

of the n-sphere of constant radius R in n dimensions reaches a maximum for dimension  if

if  and

and  if

if  .[2]

.[2]

Examples

The 0-ball consists of a single point. The 0-dimensional Hausdorff measure is the number of points in a set, so

.

.

The unit 1-ball is the interval ![[-1,1]](../I/m/d060b17b29e0dae91a1cac23ea62281a.png) of length 2. So,

of length 2. So,

The 0-sphere consists of its two end-points,  . So

. So

.

.

The unit 1-sphere is the unit circle in the Euclidean plane, and this has circumference (1-dimensional measure)

The region enclosed by the unit 1-sphere is the 2-ball, or unit disc, and this has area (2-dimensional measure)

Analogously, in 3-dimensional Euclidean space, the surface area (2-dimensional measure) of the unit 2-sphere is given by

and the volume enclosed is the volume (3-dimensional measure) of the unit 3-ball, given by

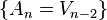

Recurrences

The surface area, or properly the n-dimensional volume, of the n-sphere at the boundary of the (n + 1)-ball of radius  is related to the volume of the ball by the differential equation

is related to the volume of the ball by the differential equation

,

,

or, equivalently, representing the unit n-ball as a union of concentric (n − 1)-sphere shells,

So,

.

.

We can also represent the unit (n + 2)-sphere as a union of tori, each the product of a circle (1-sphere) with an n-sphere. Let  and

and  , so that

, so that  and

and  . Then,

. Then,

Since  , the equation

, the equation

holds for all n.

holds for all n.

This completes our derivation of the recurrences:

Closed forms

Combining the recurrences, we see that  . So it is simple to show by induction on k that,

. So it is simple to show by induction on k that,

where  denotes the double factorial, defined for odd integers 2k + 1 by (2k + 1)!! = 1 · 3 · 5 ··· (2k − 1) · (2k + 1).

denotes the double factorial, defined for odd integers 2k + 1 by (2k + 1)!! = 1 · 3 · 5 ··· (2k − 1) · (2k + 1).

In general, the volume, in n-dimensional Euclidean space, of the unit n-ball, is given by

where  is the gamma function, which satisfies

is the gamma function, which satisfies  .

.

By multiplying  by

by  , differentiating with respect to

, differentiating with respect to  , and then setting

, and then setting  , we get the closed form

, we get the closed form

.

.

Other relations

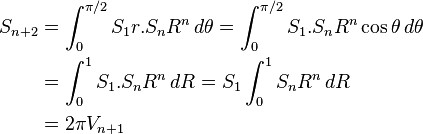

The recurrences can be combined to give a "reverse-direction" recurrence relation for surface area, as depicted in the diagram:

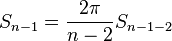

Index-shifting n to n − 2 then yields the recurrence relations:

where S0 = 2, V1 = 2, S1 = 2π and V2 = π.

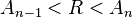

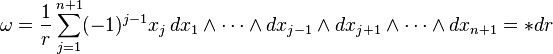

The recurrence relation for  can also be proved via integration with 2-dimensional polar coordinates:

can also be proved via integration with 2-dimensional polar coordinates:

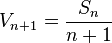

Spherical coordinates

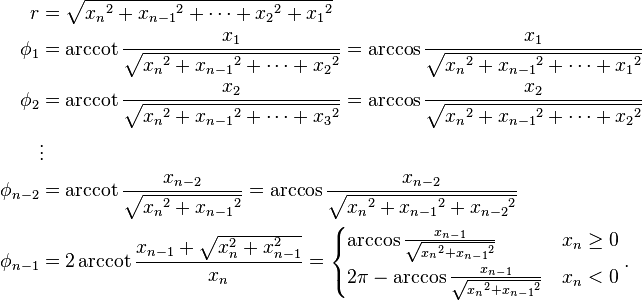

We may define a coordinate system in an n-dimensional Euclidean space which is analogous

to the spherical coordinate system defined for 3-dimensional Euclidean space, in which the coordinates consist of a radial coordinate,  and n − 1 angular coordinates

and n − 1 angular coordinates  where

where  ranges over

ranges over  radians (or over [0, 360) degrees) and the other angles range over

radians (or over [0, 360) degrees) and the other angles range over ![[0, \pi] \,](../I/m/034433dd3d56b07927de450b1a2b0acd.png) radians (or over [0, 180] degrees). If

radians (or over [0, 180] degrees). If  are the Cartesian coordinates, then we may compute

are the Cartesian coordinates, then we may compute  from

from  with:

with:

Except in the special cases described below, the inverse transformation is unique:

where if  for some

for some  but all of

but all of  are zero then

are zero then  when

when  , and

, and  radians (180 degrees) when

radians (180 degrees) when  .

.

There are some special cases where the inverse transform is not unique;  for any

for any  will be ambiguous whenever all of

will be ambiguous whenever all of  are zero; in this case

are zero; in this case  may be chosen to be zero.

may be chosen to be zero.

Spherical volume element

Expressing the angular measures in radians, the volume element in n-dimensional Euclidean space will be found from the Jacobian of the transformation:

and the above equation for the volume of the n-ball can be recovered by integrating:

The volume element of the (n-1)–sphere, which generalizes the area element of the 2-sphere, is given by

The natural choice of an orthogonal basis over the angular coordinates is a product of ultraspherical polynomials,

for j = 1, 2, ..., n − 2, and the e isφj for the angle j = n − 1 in concordance with the spherical harmonics.

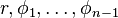

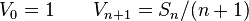

Stereographic projection

- Main article: Stereographic projection

Just as a two-dimensional sphere embedded in three dimensions can be mapped onto a two-dimensional plane by a stereographic projection, an n-sphere can be mapped onto an n-dimensional hyperplane by the n-dimensional version of the stereographic projection. For example, the point ![\ [x,y,z]](../I/m/96155b1bc331454ce48057c12f9596a1.png) on a two-dimensional sphere of radius 1 maps to the point

on a two-dimensional sphere of radius 1 maps to the point ![\left[\frac{x}{1-z},\frac{y}{1-z}\right]](../I/m/3250235e1791f957399ea682325dd273.png) on the

on the  plane. In other words,

plane. In other words,

Likewise, the stereographic projection of an n-sphere  of radius 1 will map to the

of radius 1 will map to the  dimensional hyperplane

dimensional hyperplane  perpendicular to the

perpendicular to the  axis as

axis as

Generating random points

Uniformly at random from the (n − 1)-sphere

To generate uniformly distributed random points on the (n − 1)-sphere (i.e., the surface of the n-ball), Marsaglia (1972) gives the following algorithm.

Generate an n-dimensional vector of normal deviates (it suffices to use N(0, 1), although in fact the choice of the variance is arbitrary),  .

.

Now calculate the "radius" of this point,

The vector  is uniformly distributed over the surface of the unit n-ball.

is uniformly distributed over the surface of the unit n-ball.

Examples

For example, when n = 2 the normal distribution exp(−x12) when expanded over another axis exp(−x22) after multiplication takes the form exp(−x12−x22) or exp(−r2) and so is only dependent on distance from the origin.

Alternatives

Another way to generate a random distribution on a hypersphere is to make a uniform distribution over a hypercube that includes the unit hyperball, exclude those points that are outside the hyperball, then project the remaining interior points outward from the origin onto the surface. This will give a uniform distribution, but it is necessary to remove the exterior points. As the relative volume of the hyperball to the hypercube decreases very rapidly with dimension, this procedure will succeed with high probability only for fairly small numbers of dimensions.

Wendel's theorem gives the probability that all of the points generated will lie in the same half of the hypersphere.

Uniformly at random from the n-ball

With a point selected from the surface of the n-ball uniformly at random, one needs only a radius to obtain a point uniformly at random within the n-ball. If u is a number generated uniformly at random from the interval [0, 1] and x is a point selected uniformly at random from the surface of the n-ball then u1/nx is uniformly distributed over the entire unit n-ball.

Specific spheres

- 0-sphere

- The pair of points {±R} with the discrete topology for some R > 0. The only sphere that is not path-connected. Has a natural Lie group structure; isomorphic to O(1). Parallelizable.

- 1-sphere

- Also known as the circle. Has a nontrivial fundamental group. Abelian Lie group structure U(1); the circle group. Topologically equivalent to the real projective line, RP1. Parallelizable. SO(2) = U(1).

- 2-sphere

- Also known as the sphere. Complex structure; see Riemann sphere. Equivalent to the complex projective line, CP1. SO(3)/SO(2).

- 3-sphere

- Also known as the glome. Parallelizable, Principal U(1)-bundle over the 2-sphere, Lie group structure Sp(1), where also

.

.- 4-sphere

- Equivalent to the quaternionic projective line, HP1. SO(5)/SO(4).

- 5-sphere

- Principal U(1)-bundle over CP2. SO(6)/SO(5) = SU(3)/SU(2).

- 6-sphere

- Almost complex structure coming from the set of pure unit octonions. SO(7)/SO(6) = G2/SU(3). See also: 6-sphere coordinates

- 7-sphere

- Topological quasigroup structure as the set of unit octonions. Principal Sp(1)-bundle over S4. Parallelizable. SO(8)/SO(7) = SU(4)/SU(3) = Sp(2)/Sp(1) = Spin(7)/G2 = Spin(6)/SU(3). The 7-sphere is of particular interest since it was in this dimension that the first exotic spheres were discovered.

- 8-sphere

- Equivalent to the octonionic projective line OP1.

- 23-sphere

- A highly dense sphere-packing is possible in 24-dimensional space, which is related to the unique qualities of the Leech lattice.

See also

- Affine sphere

- Conformal geometry

- Homology sphere

- Homotopy groups of spheres

- Homotopy sphere

- Hyperbolic group

- Hypercube

- Inversive geometry

- Loop (topology)

- Manifold

- Möbius transformation

- Orthogonal group

- Spherical cap

- Volume of an n-ball

Notes

- ↑ James W. Vick (1994). Homology theory, p. 60. Springer

- ↑ Loskot, Pavel (November 2007). "On Monotonicity of the Hypersphere Volume and Area". Journal of Geometry 87 (1-2): 96–98. doi:10.1007/s00022-007-1891-1.

References

- Flanders, Harley (1989). Differential forms with applications to the physical sciences. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-66169-8..

- Moura, Eduarda; Henderson, David G. (1996). Experiencing geometry: on plane and sphere. Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-373770-7 (Chapter 20: 3-spheres and hyperbolic 3-spaces.)

- Weeks, Jeffrey R. (1985). The Shape of Space: how to visualize surfaces and three-dimensional manifolds. Marcel Dekker. ISBN 978-0-8247-7437-0 (Chapter 14: The Hypersphere)

- Marsaglia, G. (1972). "Choosing a Point from the Surface of a Sphere". Annals of Mathematical Statistics 43 (2): 645–646. doi:10.1214/aoms/1177692644.

- Huber, Greg (1982). "Gamma function derivation of n-sphere volumes". Am. Math. Monthly 89 (5): 301–302. doi:10.2307/2321716. JSTOR 2321716. MR 1539933.

- Barnea, Nir (1999). "Hyperspherical functions with arbitrary permutational symmetry: Reverse construction". Phys. Rev. A 59 (2): 1135–1146. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.59.1135.

External links

- Exploring Hyperspace with the Geometric Product

- Properties of Spherical Coordinates in n Dimensions

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Hypersphere", MathWorld.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

![\begin{array}{ll}

S_{n}(R) &= \displaystyle{\frac{2\pi^{(n + 1)/2}}{\Gamma(\frac{n+1}{2})}R^{n}} \\[1 em]

V_n(R) &= \displaystyle{\frac{\pi^{n/2}}{\Gamma(\frac{n}{2} + 1)}}R^n

\end{array}](../I/m/21a668e2c8449b3a75ad2a332283d8b4.png)

![\begin{align}

V_n

& = \int_0^1 \int_0^{2\pi} V_{n-2}(\sqrt{1-r^2})^{n-2} \, r \, d\theta \, dr \\[6pt]

& = \int_0^1 \int_0^{2\pi} V_{n-2} (1-r^2)^{n/2-1}\, r \, d\theta \, dr \\[6pt]

& = 2 \pi V_{n-2} \int_{0}^{1} (1-r^2)^{n/2-1}\, r \, dr \\[6pt]

& = 2 \pi V_{n-2} \left[ -\frac{1}{n}(1-r^2)^{n/2} \right]^{r=1}_{r=0} \\[6pt]

& = 2 \pi V_{n-2} \frac{1}{n} = \frac{2 \pi}{n} V_{n-2}.

\end{align}](../I/m/0b5ddc9347703a728fc1874f71df2845.png)

![\begin{align}

d^nV & =

\left|\det\frac{\partial (x_i)}{\partial(r,\phi_j)}\right|

dr\,d\phi_1 \, d\phi_2\cdots d\phi_{n-1} \\[6pt]

& = r^{n-1}\sin^{n-2}(\phi_1)\sin^{n-3}(\phi_2)\cdots \sin(\phi_{n-2})\,

dr\,d\phi_1 \, d\phi_2\cdots d\phi_{n-1}

\end{align}](../I/m/260b4bd7f1d5a88d105a336507724913.png)

![\begin{align}

& {} \quad \int_0^\pi \sin^{n-j-1}(\phi_j) C_s^{((n-j-1)/2)}(\cos \phi_j)C_{s'}^{((n-j-1)/2)}(\cos\phi_j) \, d\phi_j \\[6pt]

& = \frac{\pi 2^{3-n+j}\Gamma(s+n-j-1)}{s!(2s+n-j-1)\Gamma^2((n-j-1)/2)}\delta_{s,s'}

\end{align}](../I/m/04f260e10ce9625af6e38fdd25c42333.png)

![\ [x,y,z] \mapsto \left[\frac{x}{1-z},\frac{y}{1-z}\right].](../I/m/95c84f377fabe5ebd1e04589631ad42f.png)

![[x_1,x_2,\ldots,x_n] \mapsto \left[\frac{x_1}{1-x_n},\frac{x_2}{1-x_n},\ldots,\frac{x_{n-1}}{1-x_n}\right].](../I/m/70fe520ba200d5143473a38d28070972.png)