Asana

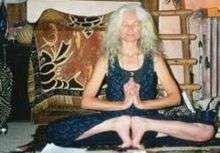

In yoga, asana refers both to the place in which a practitioner (yogi if male, yogini if female) sits and the posture in which he or she sits.[1] In the Yoga Sutras, Patanjali defines "asana" as "to be seated in a position that is firm, but relaxed".[2] Patanjali mentions the ability to sit for extended periods as one of the eight limbs of his system, known as ashtanga yoga.[3]

Asanas are also performed as physical exercise where they are sometimes referred to as "yoga postures" or "yoga positions".[4] Some asanas are arguably performed by many practitioners just for health purposes. Asanas do promote good health, although in different ways compared to physical exercises, "placing the physical body in positions that cultivate also awareness, relaxation and concentration".[5]

Terminology

Asana (/ˈɑːsənə/; ![]() listen Sanskrit: आसन āsana [ˈɑːsənə] 'sitting down', < आस ās 'to sit down'[6]) originally meant a sitting position. The word asana in Sanskrit does appear in many contexts denoting a static physical position, although traditional usage is specific to the practice of yoga. Traditional usage defines asana as both singular and plural. In English, plural for asana is defined as asanas. In addition, English usage within the context of yoga practice sometimes specifies yogasana or yoga asana, particularly with regard to the system of the Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga. However, yogasana is also the name of a particular posture that is not specifically associated with the Vinyasa system, and that while "ashtanga" (small 'a') refers to the eight limbs of Yoga delineated below, Ashtanga (capital 'A') refers to the specific system of Yoga developed by Sri Krishnamacharya at the Mysore Palace.

listen Sanskrit: आसन āsana [ˈɑːsənə] 'sitting down', < आस ās 'to sit down'[6]) originally meant a sitting position. The word asana in Sanskrit does appear in many contexts denoting a static physical position, although traditional usage is specific to the practice of yoga. Traditional usage defines asana as both singular and plural. In English, plural for asana is defined as asanas. In addition, English usage within the context of yoga practice sometimes specifies yogasana or yoga asana, particularly with regard to the system of the Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga. However, yogasana is also the name of a particular posture that is not specifically associated with the Vinyasa system, and that while "ashtanga" (small 'a') refers to the eight limbs of Yoga delineated below, Ashtanga (capital 'A') refers to the specific system of Yoga developed by Sri Krishnamacharya at the Mysore Palace.

Yoga first originated in India. In the Yoga Sutras, Patanjali describes asana as the third of the eight limbs of classical, or Raja Yoga. Asanas are the physical movements of yoga practice and, in combination with pranayama or breathing techniques, constitute the style of yoga referred to as Hatha Yoga.[7] In the Yoga Sutra, Patanjali describes asana as a "steady and comfortable posture", referring specifically to the seated, meditative postures used for meditation practices. He further suggests that meditation is the path to samādhi; transpersonal self-realization.[8]

The eight limbs are, in order, the yamas (codes of social conduct), niyamas (self-observances), asanas (postures), pranayama (breath work), pratyahara (sense withdrawal or non-attachment), dharana (concentration), dhyana (meditation), and samadhi (realization of the true Self or Atman, and unity with Brahman (The Hindu Concept of Ultimate Reality)).[3][8]

Common practices

In the Yoga Sutras, the only rule Patanjali suggests for practicing asana is that it be "steady and comfortable".[3] The body is held poised with the practitioner experiencing no discomfort. When control of the body is mastered, practitioners are believed to free themselves from the duality of heat/cold, hunger/satiety, joy/grief, which is the first step toward the unattachment that relieves suffering.[9]

Listed below are traditional rules for performing asanas:[10][11]

- The stomach should be empty.

- Force or pressure should not be used, and the body should not tremble.

- Lower the head and other parts of the body slowly; in particular, raised heels should be lowered slowly.

- The breathing should be controlled. The benefits of asanas increase if the specific pranayama to the yoga type is performed.

- If the body is stressed, perform Corpse Pose or Child Pose

- Such asanas as Sukhasana or Shavasana help to reduce headaches.

Pranayama

Pranayama, or breath control, is the Fourth Limb of ashtanga, as set out by Patanjali in the Yoga Sutra. The practice is an integral part of both Hatha Yoga and Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga but while performing asanas. They are to be practiced and perfected as individual practices of their own.

Patanjali discusses his specific approach to pranayama in verses 2.49 through 2.51, and devotes verses 2.52 and 2.53 of the Sutra to explaining the benefits of the practice.[12] Patanjali describes pranayama as the control of the enhanced "life force" that is a result of practicing the various breathing techniques, rather than the exercises themselves.[13][14] The entirety of breathing practices includes those classified as pranayama, as well as others called svarodaya, or the "science of breath". It is a vast practice that goes far beyond the limits of pranayama as applied to asana.[15]

Surya Namaskara

Surya Namaskara, or the Salutation of the Sun, which is very commonly practiced in most forms of yoga, originally evolved as a type of worship of Surya, the Vedic solar deity, by concentrating on the Sun for vitalization. The practice supports development of the koshas, or temporal sheaths, of the subtle body.[16]

The physical aspect of the practice 'links together' twelve asanas in a dynamically expressed series. A full round of Surya namaskara is considered to be two sets of the twelve asanas, with a change in the second set where the opposing leg is moved first. The asanas included in the sun salutation differ from tradition to tradition.[17]

Benefits

The physical aspect of what is called yoga in recent years, the asanas, has been much popularized in the West due to the vast amount of benefits.[18][19][20][21][22][23][24] Physically, the practice of asanas is considered to:

- improve flexibility[25][26]

- improve strength[25][26]

- improve balance[25][26]

- reduce stress and anxiety[25][26]

- reduce symptoms of lower back pain[25][26]

- be beneficial for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)[25][26]

- increase energy and decrease fatigue[25][26]

- shorten labor and improve birth outcomes[26]

- improve physical health and quality of life measures in the elderly[26]

- improve diabetes management[27]

- reduce sleep disturbances[25][28]

- reduce hypertension[29][30]

- improve blood circulation[31]

- reduce weight[32][33]

The emphasis on the physical benefits of yoga, attributed to practice of the asanas, has de-emphasized the other traditional purposes of yoga which are to facilitate the flow of prana (vital energy) and to aid in balancing the koshas (sheaths) of the physical and metaphysical body.

Number of positions

In 1959, Swami Vishnu-devananda published a compilation of 66 basic postures and 136 variations of those postures.[34] In 1975, Sri Dharma Mittra suggested that "there are an infinite number of asanas.",[35] when he first began to catalogue the number of asanas in the Master Yoga Chart of 908 Postures, as an offering of devotion to his guru Swami Kailashananda Maharaj. He eventually compiled a list of 1300 variations, derived from contemporary gurus, yogis, and ancient and contemporary texts.[35] This work is considered one of the primary references for asanas in the field of yoga today.[36] His work is often mentioned in contemporary references for Iyengar Yoga, Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga, Sivananda Yoga, and other classical and contemporary texts.[37]

84 classic asanas

A group of 84 classic asanas taught by Lord Shiva is mentioned in several classic texts on yoga. Some of these asanas are considered highly important in the yogic canon: texts that do mention the 84 frequently single out the first four as necessary or vital to attain yogic perfection. However, a complete list of Shiva's asanas remains as yet unverified, with only one text attempting a complete corpus.

Patanjali's Yoga Sutra (4-2nd century BC) does not mention a single asana by name, merely specifying the characteristics of a good asana.[38] Later yoga texts however, do mention the 84 Classic Asanas and associate them with Shiva.

The Goraksha Samhita (10-11th century CE), or Goraksha Paddhathi, an early hatha yogic text, describes the origin of the 84 classic asanas. Observing that there are as many postures as there are beings and asserting that there are 8,400,000[39] species in all, the text states that Lord Shiva fashioned an asana for each 100,000, thus giving 84 in all, although it mentions and describes only two in detail: the siddhasana and the padmasana.[40]

The Hatha Yoga Pradipika (15th century CE) specifies that of these 84, the first four are important, namely the siddhasana, padmasana, bhadrasana and simhasana.[41]

The Hatha Ratnavali (17th century CE)[42] is one of the few texts to attempt a listing of all the 84, although 4 out of its list do not have meaningful translations from the Sanskrit, and 21 are merely mentioned without any description.[43] In all, 52 asanas of the Hatha Ratnavali are confirmed and described by the text itself, or other asana corpora.[44]

The Gheranda Samhita (late 17th century CE) asserts that Shiva taught 8,400,000 asanas, out of which 84 are preeminent, and "32 are useful in the world of mortals."[45] These 32 are: siddhasana, padmasana, bhadrasana, muktasana, vajrasana, svastikasana, simhasana, gomukhasana, virasana, dhanurasana, mritasana, guptasana, matsyasana, matsyendrasana, gorakshana, paschimottanasana, utkatasana, sankatasana, mayurasana, kukkutasana, kurmasana, uttanakurmakasana, uttanamandukasana, vrikshasana, mandukasana, garudasana, vrishasana, shalabhasana, makarasana, ushtrasana, bhujangasana, and yogasana.[46]

In Shiva Samhita (17–18th century CE) the poses ugrasana and svastikasana replace the latter two of the Hatha Yoga Pradipika.

Patenting

In 2007, public awareness of increasing attempts to patent traditional asanas in the US like for example the attempt made by Kolkata born body builder Bikram Ghosh, and others, amounting to 130 yoga-related patents in the US documented that year,[47] prompted the government of India to seek clarification on the guidelines for patenting asanas from the US Patent Office.[48][49] In 2008, to clearly show that all asanas are public knowledge and therefore not patentable, the government of India formed a team of yoga gurus, government officials, and 200 scientists from the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) to register all known asanas in a public database. The team collected asanas from 35 ancient texts including the Hindu epics, the Mahabharata, the Bhagwad Gita, and Patanjali's Yoga Sutras and as of 2010, has identified 900 asanas for the database which was named the Traditional Knowledge Digital Library and made available to patent examiners.[50][51]

See also

References

- ↑ "Patanjali Yoga sutras" by Swami Prabhavananda, published by the Sri Ramakrishna Math ISBN 81-7120-221-7 p. 111

- ↑ Verse 46, chapter II; for translation referred: "Patanjali Yoga Sutras" by Swami Prabhavananda , published by the Sri Ramakrishna Math ISBN 81-7120-221-7 p. 111

- 1 2 3 Patanjali (± 300-200 B.C.) Yoga sutras, Book II:29

- ↑ Syman, Stefanie (2010). The Subtle Body: The Story of Yoga in America. Macmillan. p. 5. ISBN 0374236763.

But many of those aspects of yoga—the ecstatic, the transcendent, the overtly Hindu, the possibly subversive, and eventually the seemingly bizarre—that you wouldn't see on the White House grounds that day and that you won’t find in most yoga classes persist, right here in America.

- ↑ Saraswati, Swami Satyananda (2008). Asana Pranayama Mudra Bandha. Yoga Publications Trust, Munger, Bihar, India. p. 12. ISBN 9788186336144.

Yogasanas have often been thought of as a form of exercise. They are not exercises, but techniques which place the physical body in positions that cultivate awareness, relaxation, concentration and meditaion.

- ↑ Monier-Williams, Sir Monier (1899). A Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Oxford Clarendon Press, p. 159

- ↑ Arya, Pandit Usharbudh (aka Swami Veda Bharati) (1977/1985). Philosophy of Hatha Yoga. Himalayan Institute Press, Pennsylvania.

- 1 2 Swami Prabhavananda (Translator), Christopher Isherwood (Translator), Patanjali (Author) (1996, 2nd ed.). Vedanta Press.

- ↑ Feuerstein, Georg (2003). The Deeper Dimensions of Yoga: Theory and Practice. Shambhala Publications, Massacheusetts.

- ↑ Desikachar, T. K. V. (1999). The Heart of Yoga: Developing a Personal Practice. Rochester, Vt: Inner Traditions International. ISBN 0-89281-764-X.

- ↑ Taimni, I. K. (1996). The Science of Yoga. Adyar, Madras: The Theosophical Publishing House. ISBN 81-7059-212-7. Eight reprint edition.

- ↑ Kriyananda, Swami. The Art and Science of Raja Yoga, ISBN 81-208-1876-8

- ↑ Yogananda, Paramhansa, The Essence of Self-Realization, ISBN 0-916124-29-0

- ↑ Rama, Swami (1988). Path of Fire and Light, Vols. 1 & 2. Himalayan Institute Press, Pennsylvania; India.

- ↑ Master Murugan, Chillayah (20 October 2012). "Yoga Asana and Surya Namaskara". Silambam. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ↑ Easa, Leila. "How to Salute the Sun". Yoga Journal. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ↑ "The Five Mental and Psychological Benefits of Yoga". Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- ↑ "Yoga for anxiety and depression". Harvard University. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- ↑ "38 Health Benefits of Yoga". Yoga Journal. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- ↑ "Yoga Health Benefits: Flexibility, Strength, Posture, and More". WEBMD. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- ↑ "Yoga and Spirituality". Art of Living. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- ↑ "Spiritual Benefits of Yoga". Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- ↑ "101 Benefits of Yoga". Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Ross A, Thomas S (January 2010). "The health benefits of yoga and exercise: a review of comparison studies". J Altern Complement Med 16 (1): 3–12. doi:10.1089/acm.2009.0044. PMID 20105062.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Hayes M, Chase S (March 2010). "Prescribing yoga". Prim. Care 37 (1): 31–47. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2009.09.009. PMID 20188996.

- ↑ Alexander GK, Taylor AG, Innes KE, Kulbok P, Selfe TK (2008). "Contextualizing the effects of yoga therapy on diabetes management: a review of the social determinants of physical activity". Fam Community Health 31 (3): 228–39. doi:10.1097/01.FCH.0000324480.40459.20. PMC 2720829. PMID 18552604.

- ↑ Gooneratne NS (February 2008). "Complementary and alternative medicine for sleep disturbances in older adults". Clin. Geriatr. Med. 24 (1): 121–38, viii. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2007.08.002. PMC 2276624. PMID 18035236.

- ↑ Silverberg DS (September 1990). "Non-pharmacological treatment of hypertension". J Hypertens Suppl 8 (4): S21–6. PMID 2258779.

- ↑ Labarthe D, Ayala C (May 2002). "Nondrug interventions in hypertension prevention and control". Cardiol Clin 20 (2): 249–63. doi:10.1016/s0733-8651(01)00003-0. PMID 12119799.

- ↑ "Yoga to Improve Circulation". livestrong. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ↑ "Simple Yoga Asanas for Weight Loss". myipub. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ↑ "Yoga for Weight Loss – Is it Appropriate?". ishafoundation. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ↑ Vishnu-devananda, Swami (1959) The Complete Illustrated Book of Yoga

- 1 2 Mittra, Dharma, (2003) Asanas: 608 Yoga Poses", ISBN 1-57731-402-6

- ↑ "Yoga.com". Yoga.com. 2005-02-27. Retrieved 2011-10-29.

- ↑ Yoga Journal, Talking Shop with Dharma MittraDharma Mittra - the master teacher behind the 908 yoga asana poster -shares his insight on the practice

- ↑ Patanjali Yoga Sutra, Book 2

- ↑ Singh, T D; Hinduism and Science

- ↑ Goraksha Paddhathi

- ↑ Chapter 1, 'On Asanas', Hatha Yoga Pradipika

- ↑ Yoga Institute (Santacruz East Bombay India) (1988). Cyclopaedia Yoga. Yoga Institute. p. 32. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ↑ Summa

- ↑ Homage to the Source

- ↑ Mallinson, James (2004). The Gheranda samhita: the original Sanskrit and an English translation. YogaVidya.com. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-9716466-3-6. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ↑ Mallinson, James (2004). The Gheranda samhita: the original Sanskrit and an English translation. YogaVidya.com. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-9716466-3-6. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ↑ "US patent on yoga? Indian gurus fume". The Times of India. May 18, 2007. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ↑ "Indian Government in Knots Over U.S. Yoga Patents". ABC News. May 22, 2007.

- ↑ "GRANT OF PATENTS ON YOGA BY UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE – THE FACTUAL POSITION". PIB, Ministry of Commerce & Industry. June 13, 2007.

- ↑ "India Documents 900 Yoga Poses to Block Patents" (PDF). Voice of America News. 11 Jun 2010.

- ↑ Nelson, Dean (23 Feb 2009). "India moves to patent yoga poses in bid to protect traditional knowledge". The Daily Telegraph (London).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Asana. |

| ||||||||||