Zombie (folklore)

| |

| Grouping | Legendary creature |

|---|---|

| Sub grouping | Undead |

| Similar creatures | Revenant |

| Parents | Bantu mythology |

| Mythology | Caribbean folklore |

| Other name(s) | Zombi, Zonbi |

| Country | Haiti |

| Zombies |

|---|

|

Overview |

|

Zombies in media |

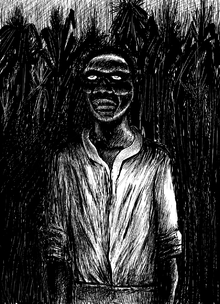

In Haitian folklore, a zombie (Haitian French: zombi, Haitian Creole: zonbi) is an animated corpse raised by magical means, such as witchcraft.[1]

The concept has been popularly associated with the Vodou religion, but it plays no part in that faith's formal practices.

Etymology

The English word "zombie" is first recorded in 1819, in a history of Brazil by the poet Robert Southey, in the form of "zombi".[2] The Oxford English Dictionary gives the origin of the word as West African, and compares it to the Kongo words "nzambi" (god) and "zumbi" (fetish).

Haitian tradition

Zombies featured widely in Haitian rural folklore, as dead persons physically revived by the act of necromancy of a bokor sorcerer (the bokor is a witch-like figure to be distinguished from the houngan priests and mambo priestesses of the formal Vodou religion). Zombies remain under the control of the bokor as their personal slaves, since they have no will of their own.

There also exists within the Haitian tradition, an incorporeal type of zombie, the "zombie astral", which is a part of the human soul that is captured by a bokor and used to enhance the bokor's spiritual power. Bokors produce and sell specially-decorated bottles to clients with a zombie astral inside, for the purposes of luck, healing or business success. It is believed that after a time God will take the soul back and so the zombie is a temporary spiritual entity.[3]

It has been suggested that the two types of zombie reflect soul dualism, a belief of Haitian Vodou. Each type of legendary zombie is therefore missing one half of its soul (the flesh or the spirit).[4]

The zombie belief has its roots in traditions brought to Haiti by enslaved Africans, and their subsequent experiences in the New World. It was thought that the Vodou deity Baron Samedi would gather them from their grave to bring them to a heavenly afterlife in Africa ("Guinea"), unless they had offended him in some way, in which case they would be forever a slave after death, as a zombie. A zombie could also be saved by feeding them salt. A number of scholars have pointed out the significance of the zombie figure as a metaphor for the history of slavery in Haiti.[5]

While most scholars have associated the Haitian zombie with African cultures, a connection has also been suggested to the island's indigenous Taíno people, partly based on an early account of native shamanist practices written by the Hieronymite monk Ramón Pané, a companion of Christopher Columbus.[6][7][8]

The Haitian zombie phenomenon first attracted widespread international attention during the United States occupation of Haiti (1915 - 1934), when a number of case histories of purported "zombies" began to emerge. The first popular book covering the topics was William Seabrook's The Magic Island (1929).

Seabrooke cited the Haitian criminal code as what he considered official recognition of zombies - Article 246 (passed 1864), later to be used in promotional materials for the 1932 film White Zombie, reads in part:

Also shall be qualified as attempted murder the employment which may be made by any person of substances which, without causing actual death, produce a lethargic coma more or less prolonged. If, after the administering of such substances, the person has been buried, the act shall be considered murder no matter what result follows.[9]

In 1937, while researching folklore in Haiti, Zora Neale Hurston encountered the case of a woman who appeared in a village, and a family claimed she was Felicia Felix-Mentor, a relative who had died and been buried in 1907 at the age of 29. However, the woman had been examined by a doctor, who found on X-ray that she did not have the leg fracture that Felix-Mentor was known to have had.[10] Hurston pursued rumors that the affected persons were given a powerful psychoactive drug, but she was unable to locate individuals willing to offer much information. She wrote: "What is more, if science ever gets to the bottom of Vodou in Haiti and Africa, it will be found that some important medical secrets, still unknown to medical science, give it its power, rather than gestures of ceremony."[11]

Chemical hypothesis

Several decades after Hurston's work, Wade Davis, a Harvard ethnobotanist, presented a pharmacological case for zombies in a 1983 paper in the Journal of Ethnopharmacology,[12] and later in two popular books, The Serpent and the Rainbow (1985) and Passage of Darkness: The Ethnobiology of the Haitian Zombie (1988).

Davis traveled to Haiti in 1982 and, as a result of his investigations, claimed that a living person can be turned into a zombie by two special powders being introduced into the blood stream (usually via a wound). The first, coup de poudre (French: "powder strike"), includes tetrodotoxin (TTX), a powerful and frequently fatal neurotoxin found in the flesh of the pufferfish (order Tetraodontidae). The second powder consists of deliriant drugs such as datura. Together, these powders were said to induce a deathlike state in which the will of the victim would be entirely subjected to that of the bokor. Davis also popularized the story of Clairvius Narcisse, who was claimed to have succumbed to this practice. The most ethically questioned and least scientifically explored ingredient of the powders, is part of a recently buried child's brain.[13][14][15]

The process described by Davis was an initial state of deathlike suspended animation, followed by re-awakening — typically after being buried — into a psychotic state. The psychosis induced by the drug and psychological trauma was hypothesised by Davis to reinforce culturally learned beliefs and to cause the individual to reconstruct their identity as that of a zombie, since they "knew" they were dead, and had no other role to play in the Haitian society. Societal reinforcement of the belief was hypothesized by Davis to confirm for the zombie individual the zombie state, and such individuals were known to hang around in graveyards, exhibiting attitudes of low affect.

Davis's claim has been criticized, particularly the suggestion that Haitian witch doctors can keep "zombies" in a state of pharmacologically induced trance for many years.[16] Symptoms of TTX poisoning range from numbness and nausea to paralysis — particularly of the muscles of the diaphragm — unconsciousness, and death, but do not include a stiffened gait or a deathlike trance. According to psychologist Terence Hines, the scientific community dismisses tetrodotoxin as the cause of this state, and Davis' assessment of the nature of the reports of Haitian zombies is viewed as overly credulous.[17]

Social hypothesis

Scottish psychiatrist R. D. Laing highlighted the link between social and cultural expectations and compulsion, in the context of schizophrenia and other mental illness, suggesting that schizogenesis may account for some of the psychological aspects of zombification.[18] Particularly, this suggests cases where schizophrenia manifests a state of catatonia.

Roland Littlewood, professor of anthropology and psychiatry, published a study supporting a social explanation of the zombie phenomenon in the medical journal The Lancet in 1997.[19]

The social explanation sees observed cases of people identified as zombies as a culture-bound syndrome, with a particular cultural form of adoption practiced in Haiti that unites the homeless and mentally ill with grieving families who see them as their "returned" lost loved ones, as Littlewood summarizes his findings in an article in Times Higher Education:

I came to the conclusion that although it is unlikely that there is a single explanation for all cases where zombies are recognised by locals in Haiti, the mistaken identification of a wandering mentally ill stranger by bereaved relatives is the most likely explanation in many cases. People with a chronic schizophrenic illness, brain damage or learning disability are not uncommon in rural Haiti, and they would be particularly likely to be identified as zombies.[20]

African and related legends

A Central or West African origin for the Haitian zombie has been postulated based on two etymologies in the Kongo language, nzambi ("god") and zumbi ("fetish"). This root helps form the names of several deities, including the Kongo creator deity Nzambi a Mpungu and the Louisiana serpent deity Li Grand Zombi (a local version of the Haitian Damballa), but it is in fact a generic word for a divine spirit.[21] The common African conception of beings under these names is more similar to the incorporeal "zombie astral",[3] as in the Kongo Nkisi spirits.

A related, but also often incorporeal, undead being is the jumbee of the English-speaking Caribbean, considered to be of the same etymology;[22] in the French West Indies also, local "zombies" are recognized, but these are of a more general spirit nature.[23]

The idea of physical zombie-like creatures is present in some South African cultures, where they are called xidachane in Sotho/Tsonga and maduxwane in Venda. In some communities it is believed that a dead person can be zombified by a small child.[24] It is said that the spell can be broken by a powerful enough sangoma.[25] It is also believed in some areas of South Africa that witches can zombify a person by killing and possessing the victim's body in order to force it into slave labor.[26] After rail lines were built to transport migrant workers, stories emerged about "witch trains". These trains appeared ordinary, but were staffed by zombified workers controlled by a witch. The trains would abduct a person boarding at night, and the person would then either be turned into a zombified worker, or beaten and thrown from the train a distance away from the original location.[26]

In popular culture

The figure of the zombie has appeared many times in fantasy themed fiction and entertainment as early as the 1929 novel The Magic Island by William Seabrook. Time claimed that the book "introduced 'zombi' into U.S. speech".[27] In 1932, Victor Halperin directed White Zombie, a horror film starring Bela Lugosi. This film, capitalizing on the same voodoo zombie themes as Seabrook's book of three years prior, is often regarded as the first legitimate zombie film, and introduced the word "zombie" to the wider world.[28] Other zombie-themed films include Val Lewton's I Walked With a Zombie (1943) and Wes Craven's The Serpent and the Rainbow, (1988) a heavily fictionalized account of Wade Davis' book.

The DC comics character Solomon Grundy, a villain who first appeared in a 1944 Green Lantern story, is one of the earliest depictions of a zombie in the comics medium. In 2011, Image Comics released a four issue miniseries entitled Drums, by writer El Torres and artist Abe Hernando. The story consists of Afro-Caribbean zombies that have been created using voodoo.

The zombie also appears as a metaphor in protest songs, symbolizing mindless adherence to authority, particularly in law enforcement and the armed forces. Well-known examples include Fela Kuti's 1976 album Zombie, and The Cranberries' 1994 single "Zombie".

Voodoo related zombie themes have also appeared in espionage or adventure themed works outside the horror genre. For example, the original "Jonny Quest" series (1964) and the James Bond novel and movie Live and Let Die both feature Caribbean villains who falsely claim the voodoo power of zombification in order to keep others in fear of them.

A new version of the zombie, distinct from that described in Haitian religion, has also emerged in popular culture in recent decades. This "zombie" is taken largely from George A. Romero's seminal film Night of the Living Dead,[29] which was in turn partly inspired by Richard Matheson's 1954 novel I Am Legend.[30][31] The word zombie is not used in Night of the Living Dead, but was applied later by fans.[32] The monsters in the film and its sequels, such as Dawn of the Dead and Day of the Dead, as well as its many inspired works, such as Return of the Living Dead and Zombi 2, are usually hungry for human flesh although Return of the Living Dead introduced the popular concept of zombies eating brains.

See also

References

- ↑ "Zombie". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 1998.

- ↑ "Zombie", in Oxford English Dictionary Online (subscription required), accessed 23 May 2014. The quotation cited is: "Zombi, the title whereby he [chief of Brazilian natives] was called, is the name for the Deity, in the Angolan tongue."

- ↑ 3.0 3.1

- ↑ Davis, Wade (1985), The Serpent and the Rainbow, New York: Simon & Schuster, pp 186

- ↑ Wilentz, Amy (2012-10-26). "A Zombie Is a Slave Forever". The New York Times. Haiti. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ↑ The relación of Fray Ramón Pane

- ↑ Whitehead, Neal L. (2011). Of Cannibals and Kings: Primal Anthropology in the Americas. Penn State Press. pp. 39–41.

- ↑ Edmonds, Ennis B.; Gonzalez, Michelle A. (2010). Caribbean Religious History: An Introduction. NYU Press. p. 111.

- ↑ http://www.oas.org/juridico/mla/fr/hti/fr_hti_penal.html

- ↑ Mars, Louis P. (1945). "Media life zombies for the world". Man 45 (22): 38–40. doi:10.2307/2792947. JSTOR 2792947.

- ↑ Hurston, Zora Neale. Dust Tracks on a Road. 2nd Ed. (1942: Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1984, p. 205).

- ↑ Davis, Wade (1983), The Ethnobiology of the Haitian Zombie, Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 9: 85-104.

- ↑ Davis, Wade (1985), The Serpent and the Rainbow, New York: Simon & Schuster, pp 92-95

- ↑ Davis, Wade (1988), Passage of Darkness: The Ethnobiology of the Haitian Zombie, University of North Carolina Press, pp 115-116.

- ↑ http://www.csicop.org/si/show/zombies_and_tetrodotoxin/

- ↑ Booth, W. (1988), "Voodoo Science", Science, 240: 274–277.

- ↑ Hines, Terence; "Zombies and Tetrodotoxin"; Skeptical Inquirer; May/June 2008; Volume 32, Issue 3; Pages 60–62.

- ↑ Oswald, Hans Peter (2009). Vodoo. BoD – Books on Demand. p. 39. ISBN 3-8370-5904-9.

- ↑ Littlewood, Roland; Chavannes Douyon (11 October 1997). "Clinical findings in three cases of zombification". The Lancet 350 (9084): 1094–1096. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(97)04449-8. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ↑ Littlewood, Roland (1 December 1997). "The plight of the living dead". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ↑ Moreman, Christopher M.; Rushton, Cory James (2011). Race, Oppression and the Zombie: Essays on Cross-Cultural Appropriations of the Caribbean Tradi. McFarland. p. 3.

- ↑ Moore, Brian L. (1995). Cultural Power, Resistance, and Pluralism: Colonial Guyana, 1838-1900. University of California Press. pp. 147–149.

- ↑ Dayan, Joan (1998). Haiti, History, and the Gods. University of California Press. p. 37.

- ↑ Marinovich, Greg; Silva Joao (2000). The Bang-Bang Club Snapshots from a Hidden War. William Heinemann. p. 84. ISBN 0-434-00733-1.

- ↑ Marinovich, Greg; Silva Joao (2000). The Bang-Bang Club Snapshots from a Hidden War. William Heinemann. p. 98. ISBN 0-434-00733-1.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Niehaus, Isak (June 2005). "Witches and Zombies of the South African Lowveld: Discourse, Accusations and Subjective Reality". The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 11 (2): 197–198. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9655.2005.00232.x.

- ↑ "Mumble-Jumble", Time, 9 September 1940.

- ↑ Roberts, Lee. "White Zombie is regarded as the first zombie film", November 2006.

- ↑ J.C. Maçek III (2012-06-15). "The Zombification Family Tree: Legacy of the Living Dead". PopMatters.

- ↑ Deborah Christie, Sarah Juliet Lauro, ed. (2011). Better Off Dead: The Evolution of the Zombie as Post-Human. Fordham Univ Press. p. 169. ISBN 0-8232-3447-9, 9780823234479.

- ↑ Stokes, Jasie. "Ghouls, Hell and Transcendence: The Zombie in Popular Culture from "Night of the Living Dead" to "Shaun of the Dead"". Bringham Young University. Retrieved 2012-07-25.

- ↑ Savage, Annaliza (15 June 2010). "'Godfather of the Dead' George A. Romero Talks Zombies". Wired. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

Further reading

- Ackermann, H. W.; Gauthier, J. (1991). "The Ways and Nature of the Zombi". The Journal of American Folklore 104 (414): 466–494. doi:10.2307/541551. JSTOR 541551.

- Bishop, Kyle William (2010) American Zombie Gothic: The rise and fall (and rise) of the walking dead in popular culture McFarland, Jefferson, North Carolina, ISBN 978-0-7864-4806-7

- Black, J. Anderson (2000) The Dead Walk Noir Publishing, Hereford, Herefordshire, ISBN 0-9536564-2-X

- Christie, Deborah and Sarah Juliet Lauro, eds. (2011). Better Off Dead: The Evolution of the Zombie as Post-Human. Fordham Univ Press. p. 169. ISBN 0-8232-3447-9

- Curran, Bob (2006) Encyclopedia of the Undead: A field guide to creatures that cannot rest in peace New Page Books, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, ISBN 1-56414-841-6

- Davis, E. W. (1983). "The ethnobiology of the Haitian zombi". Journal of Ethnopharmacology 9 (1): 85–104. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(83)90029-6. PMID 6668953.

- Davis, Wade (1988) Passage of Darkness: The ethnobiology of the Haitian zombie University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, ISBN 0-8078-1776-7

- Dendle, Peter (2001) The Zombie Movie Encyclopedia McFarland, Jefferson, North Carolina, ISBN 0-7864-0859-6

- Flint, David (2008) Zombie Holocaust: How the living dead devoured pop culture Plexus, London, ISBN 978-0-85965-397-8

- Forget, Thomas (2007) Introducing Zombies Rosen Publishing, New York, ISBN 1-4042-0852-6; (juvenile)

- Graves, Zachary (2010) Zombies: The complete guide to the world of the living dead Sphere, London, ISBN 978-1-84744-415-8

- Hurston, Zora Neale (2009) Tell My Horse: Voodoo and Life in Haiti and Jamaica, Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-06169-513-1

- Littlewood, R.; Douyon, C. (1997). "Clinical findings in three cases of zombification". The Lancet 350 (9084): 1094–1096. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)04449-8.

- Mars, Louis P. (1945). "Media life zombies for the world". Man 45 (22): 38–40. doi:10.2307/2792947. JSTOR 2792947. (Copy at Webster University)

- McIntosh, Shawn and Leverette, Marc (editors) (2008) Zombie Culture: Autopsies of the Living Dead Scarecrow Press, Lanham, Maryland, ISBN 0-8108-6043-0

- Moreman, Christopher M., and Cory James Rushton (editors) (2011) Race, Oppression and the Zombie: Essays on Cross-Cultural Appropriations of the Caribbean Tradition. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-5911-7.

- Moreman, Christopher M., and Cory James Rushton (editors) (2011) Zombies Are Us: Essays on the Humanity of the Walking Dead. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-5912-4.

- Russell, Jamie (2005) Book of the dead: the complete history of zombie cinema FAB, Godalming, England, ISBN 1-903254-33-7

- Waller, Gregory A. (2010) Living and the undead: slaying vampires, exterminating zombies University of Illinois Press, Urbana, Indiana, ISBN 978-0-252-07772-2